George Wythe House

Explore the original home and property of George Wythe, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, delegate to the Constitutional Convention, and first law professor of the United States. Discuss Enlightenment thinking and the ideas that shaped the Revolution, as well as the ways that free and enslaved people on the property engaged with those ideas.

Key Facts

- George Wythe, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, lived in this home with his wife Elizabeth.

- Wythe taught law students in the home, including Thomas Jefferson. The two became life-long friends.

- In 1781, during the Revolutionary War, George Washington used the Wythe house as his headquarters. He likely planned the siege of Yorktown in the home.

Life at the Wythe House

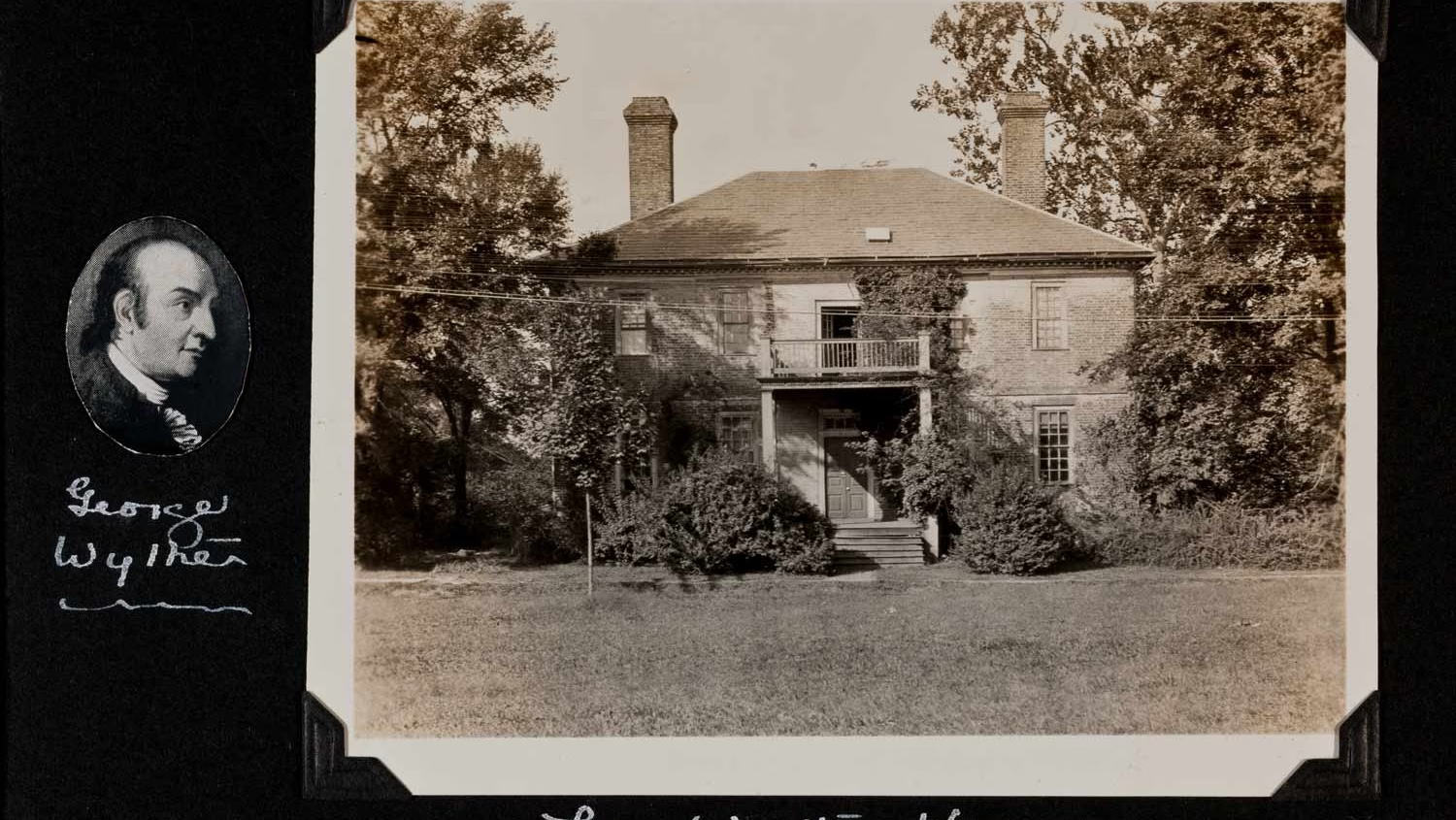

Richard Taliaferro, a wealthy Virginia planter and architect, built this home around 1755. It was around this time that his daughter Elizabeth married lawyer George Wythe, and Taliaferro gifted life use of the house and grounds.1

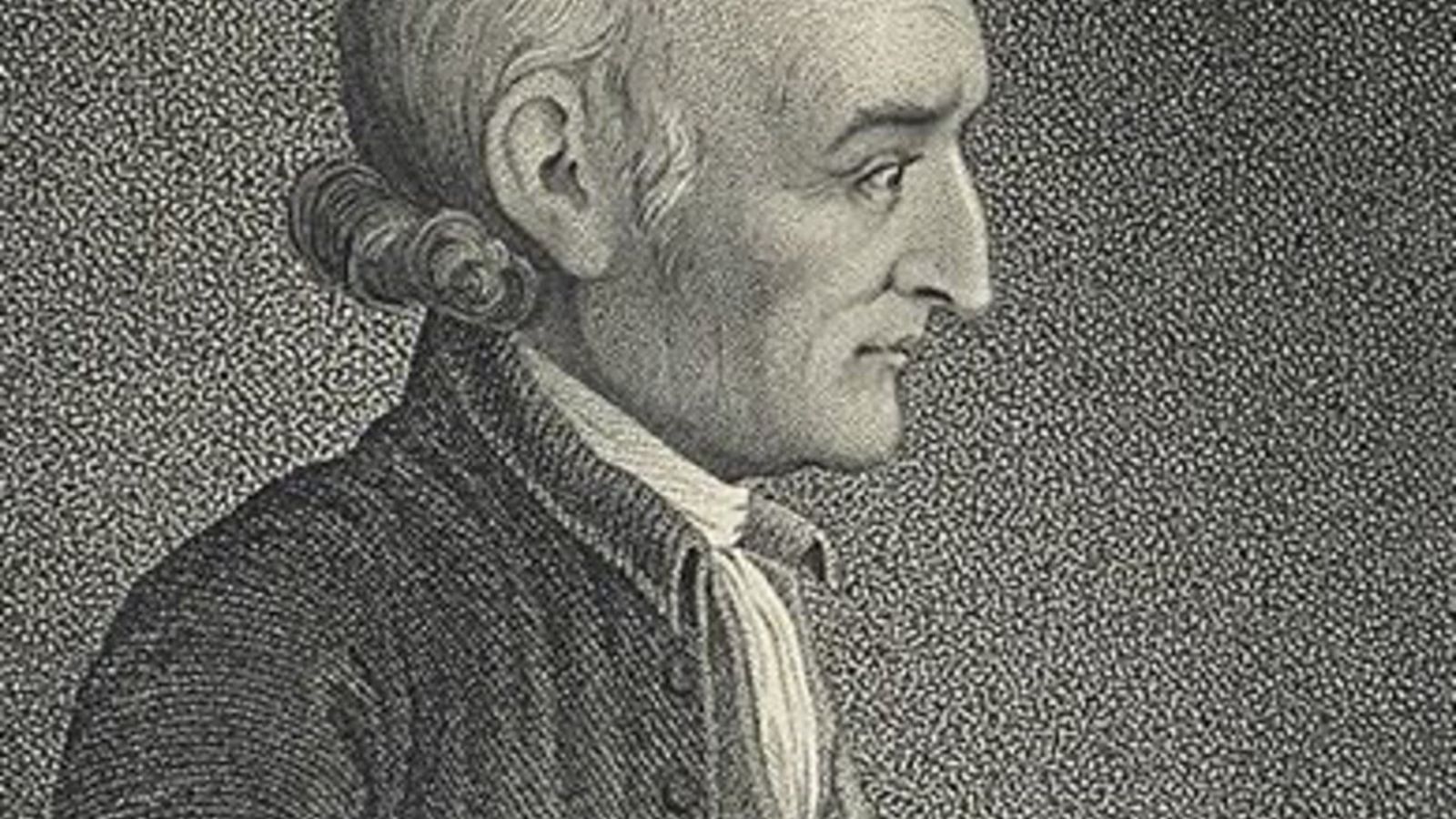

George Wythe

Known for his lifelong pursuit of virtue, George Wythe is remembered as a teacher of some of early America’s most influential minds.

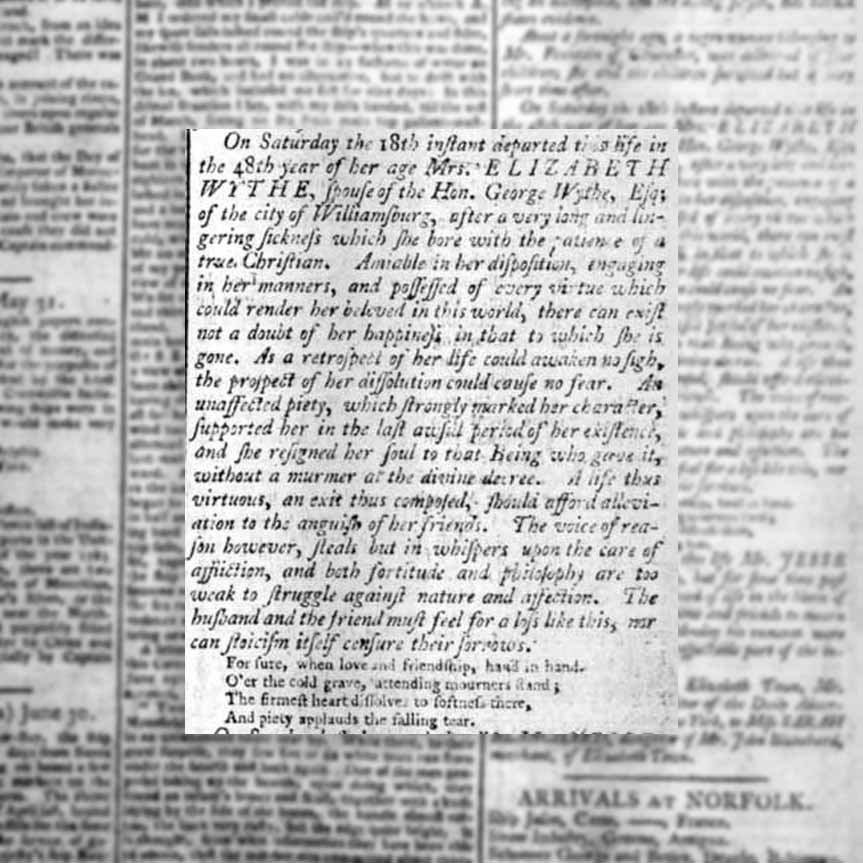

George led an active public and political life. He ran a law practice and also took in law apprentices, including Thomas Jefferson. He served as a member of the House of Burgesses, and then as its clerk. He attended the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia, signing the Declaration of Independence in 1776. In 1787, he participated in the Constitutional Convention, but returned home early because Elizabeth was ill. She died months later.2

George Wythe was a man of the Enlightenment, and he dedicated himself to understanding the world around him through study and scientific inquiry. Wythe shared his spirit of scientific inquiry, which was sometimes referred to as “natural philosophy” at the time, with his students. In around 1787, his student Littleton Waller Tazewell wrote that “Mr. Wythe imported a very complete Electrical machine together with a very fine air pump and sundry other parts of philosophical apparatus. And when this arrived, most of our leisure moments were employed in making philosophical experiments, and ascertaining the causes of the effects produced.”3

Elizabeth Wythe managed the household, including the labor of enslaved people. After Elizabeth’s death, George found himself overwhelmed by the tasks others had performed. A student boarding in the house wrote that “The necessary domestic duties occupied so much of his time, broke in upon his pursuits, and interrupted even his business and amusements. He was irritated and vexed by a thousand little occurrences he had never foreseen.”4 George’s participation in politics, business, and the pursuit of knowledge was possible in part because of Elizabeth’s competent management.

Enslavement at the Wythe House

Available records reveal that in the mid-1780s, between 14 and 17 enslaved people lived on the Wythe property.10 But by the time George Wythe moved to Richmond in 1791, the Wythe household had drastically changed.

In 1783, the first year that tax records reveal the names and number of enslaved people on the property, the Wythe house must have bustled with activity. Fourteen enslaved people lived in the home: seven adults and seven children.11 Succordia and Paul belonged to the Nelsons, Elizabeth’s cousin and her husband who were living in the home with the Wythes.12 Lydia Broadnax was likely the Wythe’s cook, and Ben may have been a coach driver.13 Depending on each person’s age, Charles, Hannah, Betty, Jenny, Little-Betty, Fanny, and her four children might have collectively been responsible for the animals on the property, the garden, the laundry, cleaning the house, serving meals, mending clothes, running errands, attending to the Wythe family, and any other task required to keep the home running smoothly.14

Lydia Broadnax

Lydia Broadnax endured slavery, worked as a cook and domestic servant, participated in community life, ran a boardinghouse, and struggled with old age and disability.

After Elizabeth’s death in 1787, George quickly began to give away or free the people he enslaved. In a deed of gift, he transferred “Cate, with her children and grandchildren, Rachel, Lydia, Lucy, Bob and Jamey” and “Fanny, with her children Paris and Isaac” to his late wife’s family.15 In a separate deed, he transferred “Rose and her three children—Edward, Betty, and a child at her breast” to another member of Elizabeth’s family.16 He freed at least 4 people: Lydia Broadnax, Polly, Charles, and Ben.17 By 1791, the Wythe household consisted of one student, William Munford, and two "Blacks above 12.”18

Explore the Interiors

Scant evidence exists as to how each room was used and furnished when the Wythes lived in the home. Colonial Williamsburg experts have re-created the home’s interiors based on what we know about other homes from the same period as well as Wythe’s social class and intellectual interests.

Washington’s Headquarters

The Wythe house hosted several key figures during the American Revolution. While George Wythe was in Philadelphia serving in the Continental Congress in 1776, he offered the use of his home to Thomas and Martha Jefferson.20

In 2025, the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation furnished the Wythe House as it might have looked like as Washington’s headquarters for special programming.

In 1781, George Washington used the home as his headquarters while he planned the siege at Yorktown.21 After the American victory at Yorktown, French commander Comte de Rochambeau stayed in the home. In December, a fire broke out at the nearby Governor’s Palace, which was being used as a hospital for American soldiers. The Wythe house “was covered all the night long with a rain of red hot ashes.” But Rochambeau’s men were able to keep the fire from spreading.22

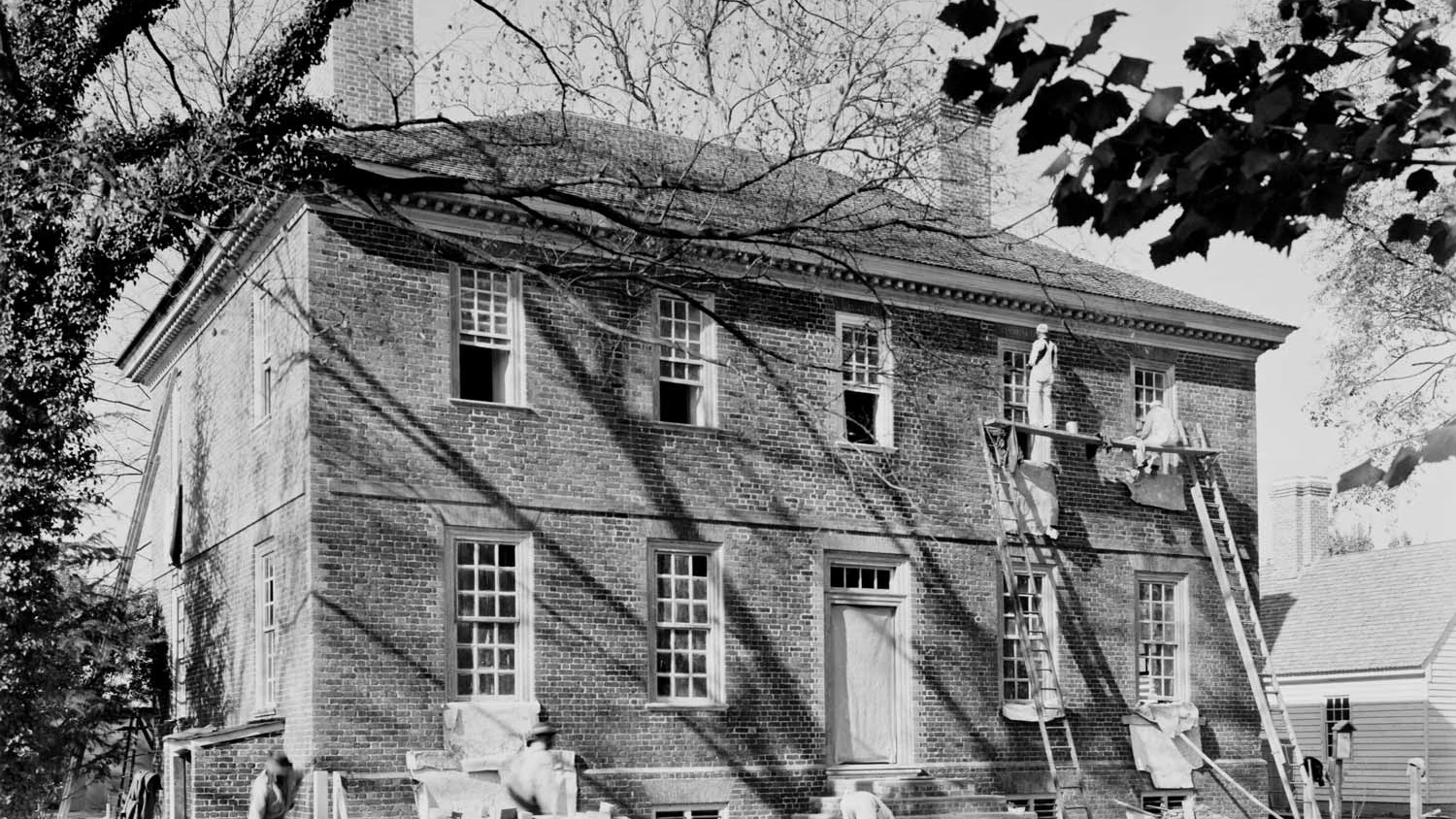

Restoration

Because George and Elizabeth had no surviving children, when Wythe moved to Richmond in 1791, he relinquished his life-right to the home.23 Afterward, it passed through many hands over the years. The original structure remained intact, even when a porch was added to the home. In 1926, it became the rectory for Bruton Parish.24 As rector, W. A. R. Goodwin oversaw a restoration of the home in the 1920s. But he had bigger plans, hoping to eventually restore the entire town to its eighteenth-century appearance. Some of his early meetings with philanthropist John D. Rockefeller, Jr. happened in the Wythe.25After Rockefeller embraced Goodwin’s vision and agreed to finance the city’s restoration, the Wythe House was restored once again by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation and opened to the public in 1940.26

Explore Virtually

Tour the original 18th-century home of George Wythe and the lives and legacies of the people who lived here.

George Wythe’s World

As a teacher and a civic leader, George Wythe shaped, and was shaped by, the Williamsburg community where he lived for over four decades.

George Wythe

Known for his lifelong pursuit of virtue, George Wythe is remembered as a teacher of some of early America’s most influential minds.

People of the Past

Eighteenth century Williamsburg was a community on the brink of revolution. Learn the stories of ordinary people during extraordinary times.

Lydia Broadnax

Lydia Broadnax was the Wythes’ enslaved cook. George Wythe freed her in 1787. When he moved to Richmond in 1791, she moved as well.

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson studied law under George Wythe. He developed a friendship with and great admiration for him.

Hamilton Usher St. George

As an overseer for Wythe, this loyalist offered supplies from Wythe’s property to Lord Dunmore during the Revolution.

Man of the Enlightenment

George Wythe was a citizen of the Enlightenment, deeply interested in politics, history, and science. He emphasized reason and individualism.

Wythe and Slavery

Wythe had a life-long and shifting relationship with slavery, both personally and professionally.

Extolling Virtues

George Wythe was known for his commitment to virtue and morals in his personal and professional life.

Places

From 1699 to 1780, Williamsburg was the political, cultural and educational center of what was then the largest, most populous, and most influential of the American colonies.

Capitol

As a lawyer, George Wythe spent a great deal of time arguing in the General Court.

Palace

George Wythe spent some evenings at the palace discussing philosophy with a small group including Thomas Jefferson.

Sources

- Mary A. Stephenson, “George Wythe House Historical Report, Block 21 Building 4,” Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1955, 2-3, link. Richard Taliaferro’s 1775 will provides the earliest written evidence of the legal ownership of the home, but George and Elizabeth lived in the home well before the will was written. In it, he granted, "my House and Lotts in the City of Williamsburg situate on the West side of Palace Street, and on the North side of the Churchyard, to my Son in Law, Mr George Wythe, and his wife, my Daughter Elizabeth, during their lives, and the Life of the longest liver of them, and afterwards to my Grand son Richard Taliaferro and his heirs forever…” “Will of Richard Taliaferro,” William and Mary College Quarterly 12, no. 2 (October, 1903), 124–25.

- For biographical details about George Wythe, see John Bailey, Jefferson’s Second Father: The Life and Strange Death of Chancellor Wythe, Signer of the Declaration of Independence (Momentum, 2013); Imogene E. Brown, American Aristides: A Biography of George Wythe (Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1981); and Alonzo Thomas Dill and Edward M. Riley, George Wythe: Teacher of Liberty (Virginia Independence Bicentennial Commission, 1979). Wythe was not in Philadelphia when the Second Continental Congress voted to declare independence, and signed the Declaration of Independence upon his return in September of 1776. See Brown, American Aristides, 144. On Elizabeth’s Death see Brown, American Aristides, 218-220.

- Littleton Waller Tazwell, “An Account and History of the Tazewell Family,” (1823), 135, William & Mary Special Collections Research Center, Swem Library, College of William & Mary.

- Ibid.

- George Wythe to John Norton, May 9, 1768; George Wythe to John Norton, August 18, 1768 in John Norton & Sons Merchants of London and Virginia: Being in the Papers of their Counting House for the Years 1750-1795, ed. Frances Norton Mason (Augustus M. Kelley Publishers, 1968), 50-51, 58.

- “To Thomas Jefferson from George Wythe, 9 March 1770,” Founders Online, link.

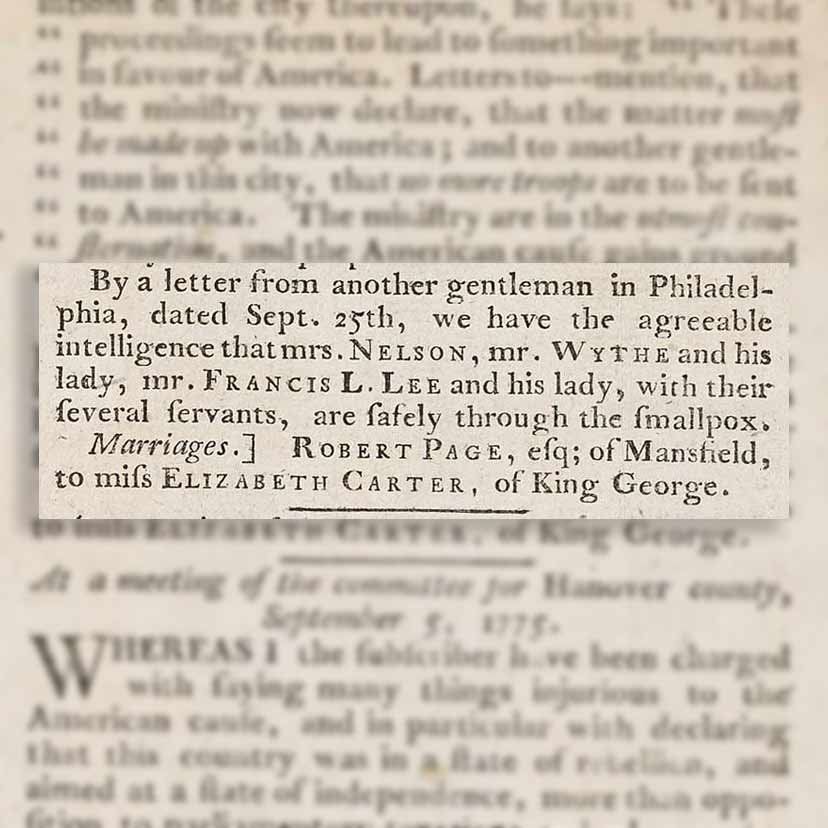

- Virginia Gazette (Purdie), October 6, 1775, link.

- Ms Account Ledger of Drs. Galt and Barraud, Williamsburg physicians, 1783-1792, in Mary A. Stephenson, “George Wythe House Historical Report, Block 21 Building 4,” Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1955, vi, link.

- Virginia Gazette, August 23, 1787, link.

- Williamsburg Personal Property Tax Lists, 1783-1861, microfilm, M-1.47, Rockefeller Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- Williamsburg Personal Property Tax List, 1783, microfilm, M-1.47, Rockefeller Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- In 1786, Succordia and Paul were no longer listed in the Wythe household but are listed in the Nelson household. Williamsburg Personal Property Tax Lists, 1783-1786.

- Ben received several tips from Thomas Jefferson, including for “coach hire.” James A. Bear and Lucia C. Stanton, eds., Jefferson’s Memorandum Books: Accounts, with Legal Records and Miscellany, 1767-1826, Volume 1 (Princeton University Press, 1997), 153, 206, 263, 455. Some evidence suggests that Lydia Broadnax was a cook, including W. Asbury Christian, Richmond: Her Past and Present (L.H. Jenkins, 1912), 64.

- “Williamsburg City Personal Property 1783-1861; Martha B. Katz-Hyman, “'In the Middle of this Poverty Some Cups and a Teapot:’ The Material Culture of Slavery in Eighteenth-Century Virginia and the Furnishing of Slave Quarters at Colonial Williamsburg,” Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1993, link.

- “George Wythe Deed to Richard Taliaferro, August 20, 1787,” William & Mary College Quarterly Historical Magazine 12, no. 1 (Oct. 1903) 125-6.

- Richmond Hustings Court Deed Book II, f. 116, September 14, 1793, microfilm, 2, Library of Virginia.

- York County, Order Book No. 6, ff. 36, 58, 81, microfilm, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- Williamsburg Personal Property Taxes, 1783-1861.

- “[Diary entry: 15 November 1769],” Founders Online, National Archives, link.

- “To Thomas Jeferson from George Wythe, 28 October 1776,” Founders Online, National Archives, link.

- St. George Tucker, September 15, [1781] in W.A.R. Goodwin, “House History File, George Wythe House Historical Report,” Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1938, link.

- Count de Rochambeau to George Washington, December 24, 1781 in W.A.R. Goodwin, “House History File, George Wythe House Historical Report,” Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1938.

- In Richard Taliaferro’s will, he stipulated that "if she [Elizabeth] shall leave lawful issue of her body living at her death, then I give the said Houses and Lotts to her and her heirs forever.” “Will of Richard Taliaferro.”

- Mary A. Stephenson, “George Wythe House Historical Report, Block 21 Building 4,” 54.

- Elizabeth Hayes, “The Background and Beginnings of the Restoration of Colonial Williamsburg, Virginia,” 1933, Colonial Williamsburg Corporate Archives.

- Mary A. Stephenson, “George Wythe House Historical Report, Block 21 Building 4,” 55.