Peter Scott: Williamsburg’s First Cabinetmaker

On This page

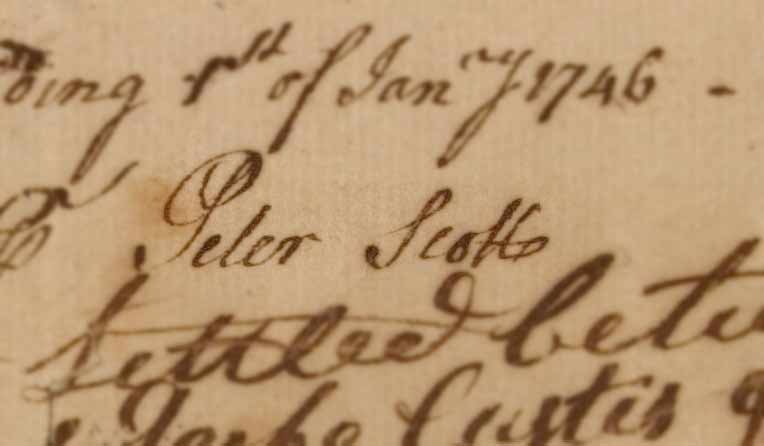

Peter Scott

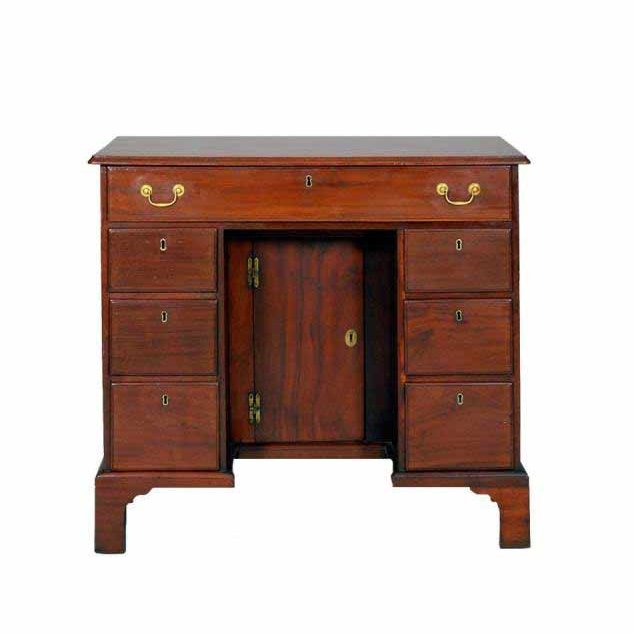

There are no portraits of Peter Scott. There is no secret diary of Peter Scott. He left behind no documents that testify to his character or beliefs. Instead, during his long career as a cabinetmaker, he built a legacy through his steady woodworking output. Across six decades, his Williamsburg shop produced an array of desks, bookcases, tables, coffins, and other furniture, some of which survive today in Colonial Williamsburg’s collections.1

Scott was born in Scotland around 1695. While little is known about his early life, he likely apprenticed in an urban cabinetmaking shop somewhere in Britain. As a young man, something drew him to emigrate to Virginia. By 1722, Scott had established himself in Williamsburg. He was the first trained cabinetmaker to work in Virginia’s capital. His work both exemplified and contributed to the style of the colony’s eighteenth-century furniture.2

Scott’s Tenement House

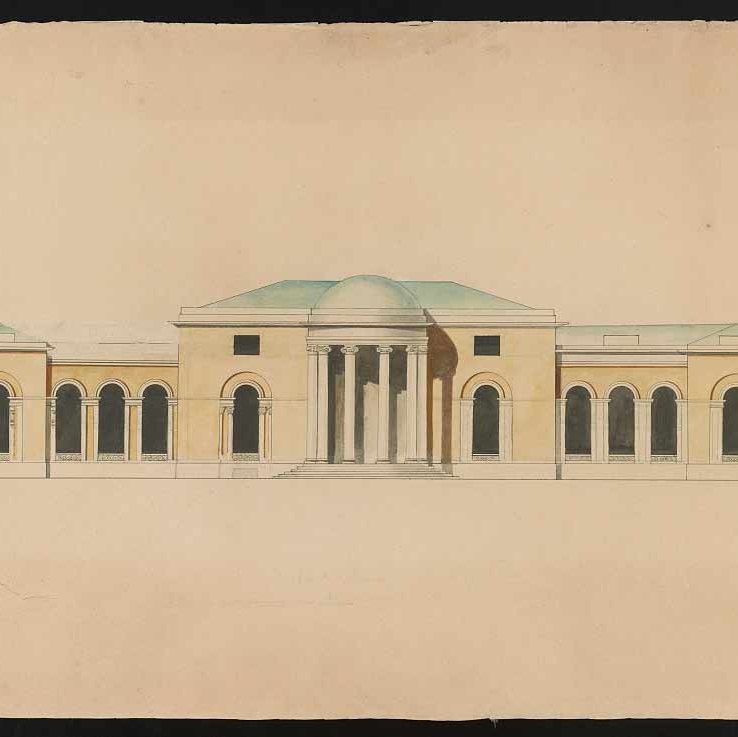

By 1733, Scott rented a tenement house on Duke of Gloucester Street, across from Bruton Parish Church, from the wealthy plantation owner John Custis IV. It remains unclear whether this property was his home, his workshop, or both. Ongoing research aims to answer that question.

Peter Scott House and Shop

Learn more about the property's history, from its purchase in 1714 by John Custis IV, to its use by prominent cabinetmaker, Peter Scott, and its accidental destruction by continental soldiers in 1775.

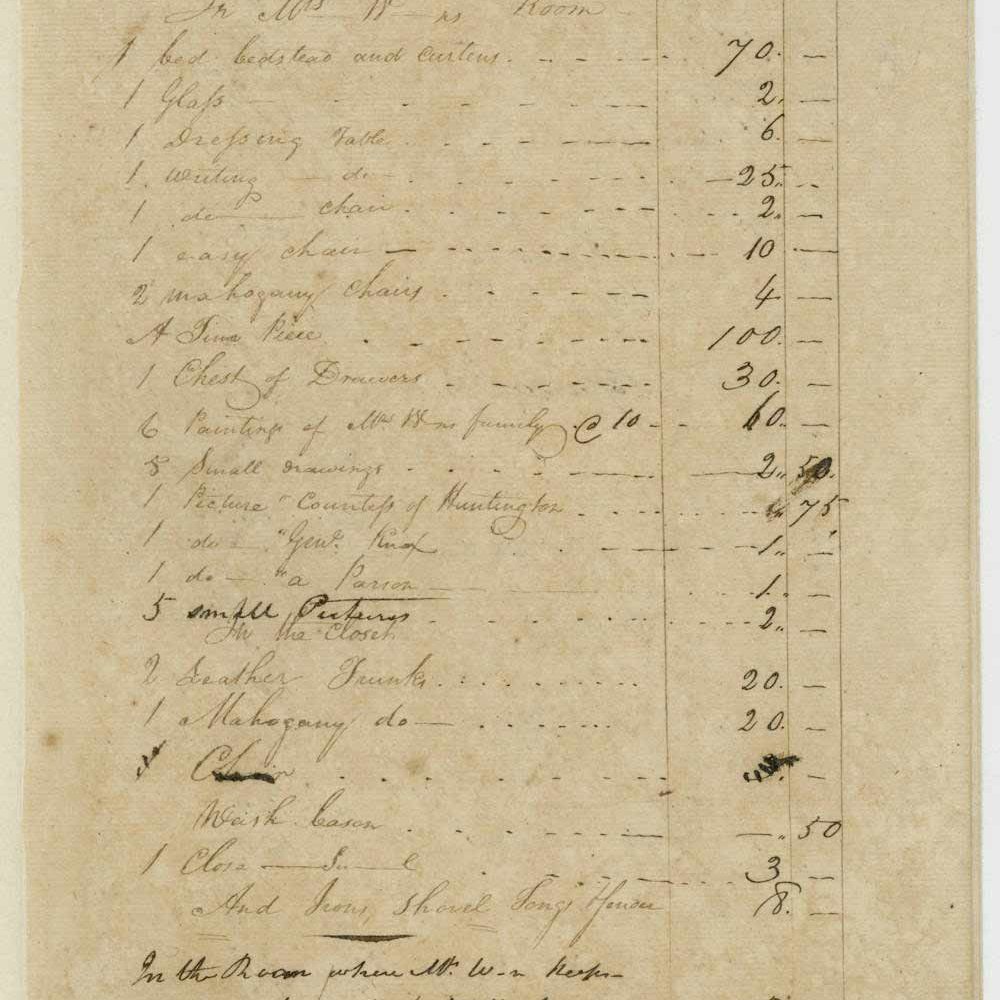

Scott occupied this property for more than half of his life. After Custis’s death, ownership turned over to his son Daniel Parke Custis, and then to Daniel’s widow Martha Custis. After she married George Washington, he took over management of the property. Only a month after Peter Scott died, the building was being used by Continental soldiers. On January 21, 1776, they accidentally burned the structure down. Edmund Randolph reported to George Washington, “Mr Custis’s Tenement, where Scott lived, opposite the Church, was burnt to the Ground, by the Negligence of some of the Soldiers, who had been quartered there.” While Washington had bigger concerns (he was leading the Continental army at the time), this information carried some financial implications for him, since it meant a loss of rental income through the Custis estate that he was managing.

Cabinetmaking

Scott’s workshop was remarkable for its longevity. He practiced the cabinetmaking trade in Williamsburg for many decades, beginning sometime after his arrival by 1722 and ending only with his death in 1775. He largely practiced the trade as he had learned it in England, adapting little except to North American wood and slightly to changing fashions.3

Scott made furniture for many members of Virginia’s eighteenth-century gentry elite, including Robert Carter III and Thomas Jefferson. Serving this distinguished clientele, Scott became financially successful. Several records document his personal loans and real estate transactions in town, including the purchase of property on a “back street” of Williamsburg, with “a good Dwelling House” and outbuildings.4

The Furniture of Peter Scott

Colonial Williamsburg owns a significant number of works attributed to Peter Scott and his workshop. Click through to learn more about this furniture.

Enslaved Workers

Like many tradespeople, Scott was an enslaver. The cabinet work that came from his workshop was likely crafted, in part, by the skillful hands of the enslaved men who worked for him. He may have also employed apprentice and journeymen workers, though he never advertised in the newspaper seeking apprentices, as some other tradespeople did.

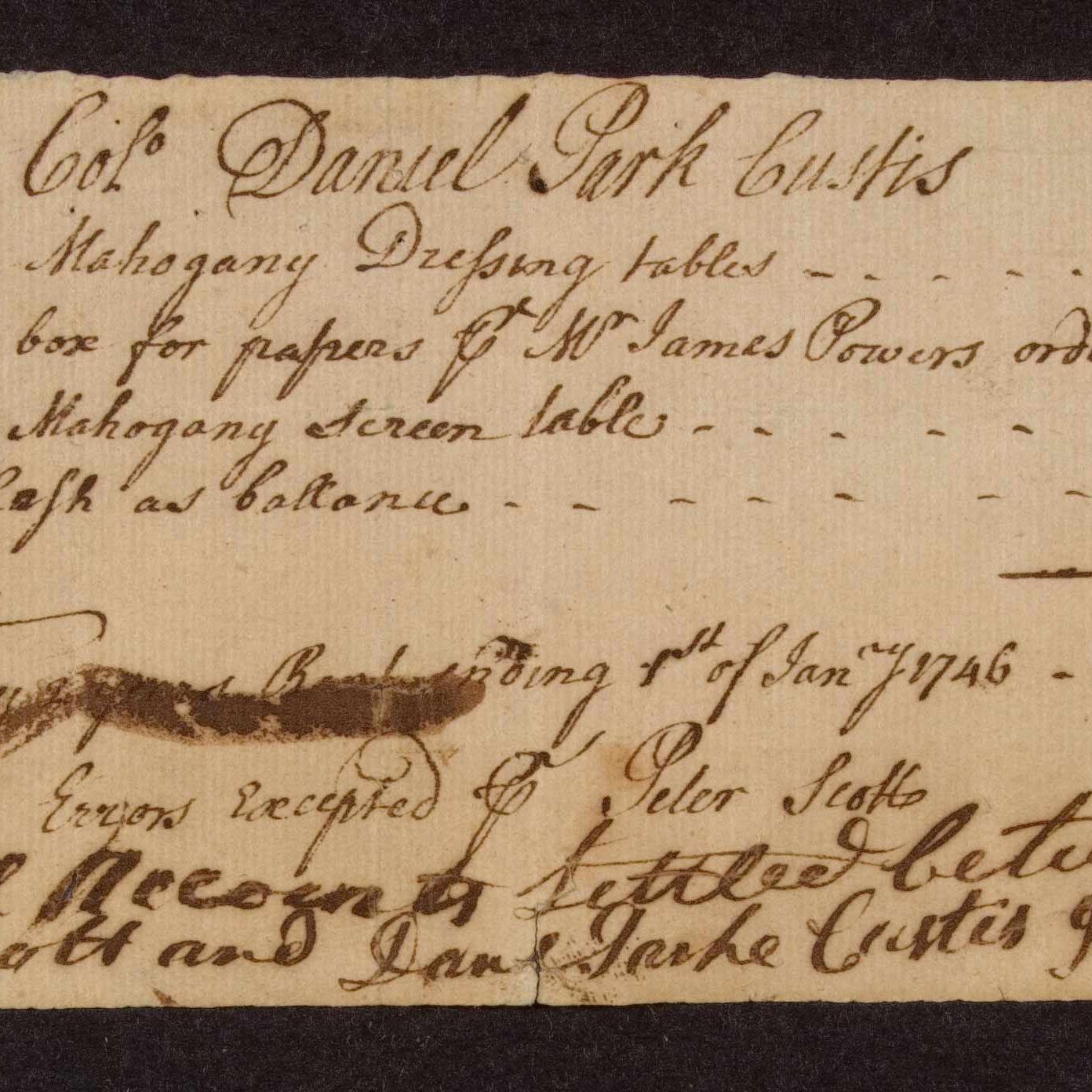

Virginia Gazette (Hunter), Sept. 12, 1755, p. 3

In 1755, Scott announced that he intended to leave for Great Britain and planned to sell his possessions at the porch of the Raleigh Tavern. While he never relocated, his advertisement offers some details about his life and his business. Most significantly, it notes that Scott was selling “Two Negroes, bred to the Business of a Cabinet-maker.” The description of these two men indicates that they were likely fully trained in the craft.5 Given the timing of this advertisement, it is possible that these enslaved men were involved in the creation of the bureau tables sold to Daniel Parke Custis in 1754.

Years after the 1755 advertisement, Thomas Jefferson recorded paying an unnamed “negro man at Peter Scott’s” in November 1772. This man may have been enslaved by Scott, or Scott may have rented his labor from another enslaver. But when Scott died three years later, a Virginia Gazette advertisement for the sale of his property did not list any enslaved people.6 No evidence has yet indicated the names or further stories of the enslaved people who worked in Scott’s cabinetmaking shop.

Legacy

Peter Scott died in December 1775, aged 81. Relatively little can be said about the details of his life. But as a longstanding member of the eighteenth-century Williamsburg community, he would have been long remembered. Today, he is known as the first cabinetmaker in Williamsburg, and an important and long-lived figure in the history of early American furniture.

More to Explore

Peter Scott House and Shop Archaeology Project

Check out artifacts as they're being discovered, talk with experts in the field and learn about the property's history.

A Tale of Twin Tables

Nearly 150 miles apart stand two twin bureau tables—one at Mount Vernon, the other now on view at the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg.

Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg

In our expansive galleries, you'll find wonderful examples of American and British antiques and decorative art from the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, as well as bold and imaginative pieces of colonial and contemporary folk art.

Sources

- Ronald L. Hurst, “Peter Scott, Cabinetmaker of Williamsburg: A Reappraisal,” American Furniture (2006), link.

- Hurst, “Peter Scott, Cabinetmaker of Williamsburg.”

- Hurst, “Peter Scott, Cabinetmaker of Williamsburg.”

- Hurst, “Peter Scott, Cabinetmaker of Williamsburg”; Virginia Gazette (Hunter), Sept. 12, 1755, p. 3, link.

- Bill Pavlak, “A very good cabinetmaker,” Fine Woodworking, Mar. 30, 2020.

- Virginia Gazette (Purdie), Jan. 5, 1776, supplement, p. 2, link.