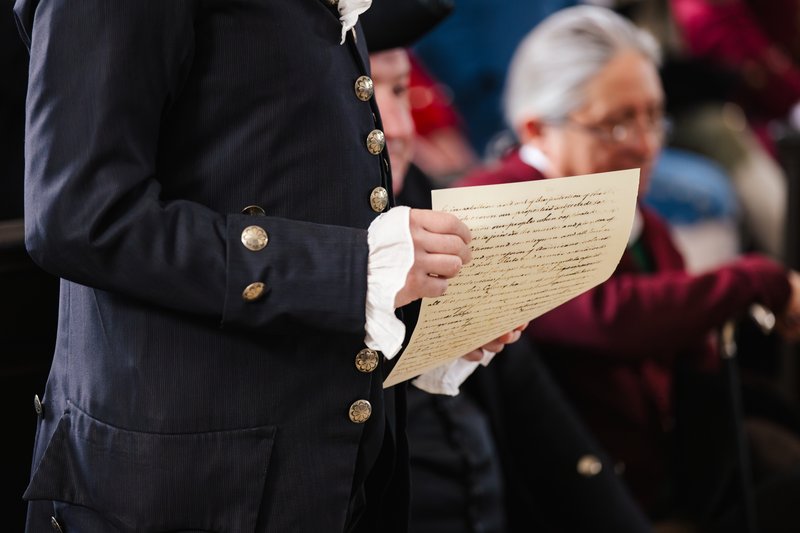

Virginia’s Independence Resolution, May 15, 1776

May 15, 1776, is one of the days that the United States began. On that day, the delegates of an elected convention of Virginia leaders, known as the Fifth Virginia Convention, met in the Williamsburg Capitol. They voted unanimously to instruct Virginia’s delegates to the Continental Congress, which was meeting in Philadelphia, “to declare the United Colonies free and independent states absolved from all allegiance to or dependence upon the crown or parliament of Great Britain.”

This bold stroke came at a decisive moment. War had begun. The pamphlet Common Sense had helped to move public opinion toward the idea of independence. At the Continental Congress in Philadelphia, many colonies’ delegations were open to moving toward independence. But to that point, no state legislature had taken the final step of instructing their delegates to propose independence. The resolution made in Williamsburg on May 15, accompanied by the creation of a committee to draft a declaration of rights and a constitution for Virginia, set colonial leaders on a path that ended with separation from Great Britain and the birth of the United States.

The Logic of Independence

In April 1775, violent conflict broke out between British forces and American colonists. Americans did not declare independence for more than a year. What took so long?

For months, many colonists remained convinced that they could reconcile with Great Britain’s government. But with each passing day, these hopes dimmed. In late 1775, news arrived that King George III had declared the colonists to be in “open and avowed Rebellion.” In November, Dunmore’s Proclamation incensed Virginia’s gentry class, and caused numerous enslaved people to seize their freedom. Pamphlets like Common Sense and essays published in newspapers like the Virginia Gazette prepared readers to imagine a new future, and a new identity, for themselves. Moreover, as the military conflict escalated, it became clear that the colonists’ best chance of success would come from allying with one of Britain’s European rivals. But an empire like France or Spain could not join forces with a gang of rebels—they could only negotiate with an independent nation.1

By the spring of 1776, arguments for independence were mounting across the colonies. But the risks remained high. The punishment for treason, after all, was death. Who would stand up and push Americans to separate from Great Britain?

Resolved

Throughout Virginia, elections for Williamsburg convention were held in early April. By that time, popular momentum had swung toward independence. According to Edmund Randolph’s recollections, many candidates for the convention won their seats by “pledging themselves” to separation.2 Many expected the convention that gathered in Williamsburg in early May would push the colony toward independence. For some, it was just a question of how it would be declared.

Meriwether Smith proposed a resolution that accused Governor Dunmore of “legalizing every Seizure, Robbery & Rapine,” and called not only for independence but also the creation of a new constitution. Another delegate based his call for independence on the “many tyrannical Acts” of Parliament and the “barbarous War” being waged against the colonists. Patrick Henry gave one of his customarily thunderous speeches and introduced a resolution that attacked Great Britain for scheming with foreign powers and Native nations, “encouraging insurrection among our slaves,” and for “a long series of oppressive acts” by the King. Henry framed the independence resolution as an act of “self-preservation.”3

Resolved… that the delegates appointed to represent this colony in General Congress be instructed to propose to that respectable body to declare the United Colonies free and independent states…

— Fifth Virginia Convention

After a lively debate, the convention’s presiding officer Edmund Pendleton developed a compromise resolution. It briefly listed a few reasons for their decision. Their petitions had been ignored. They had been declared “out of the protection of the British crown.” Foreign mercenaries had been called in. Property had been “subjected to confiscation” and Governor Dunmore had been “tempting our Slaves by every artifice” to join him. The resolution concluded by instructing Virginia’s delegates to the Continental Congress “to propose to that respectable body to declare the United Colonies free and independent states absolved from all allegiance to or dependence upon the crown or parliament of Great Britain.” They further indicated their support for the congress to explore a foreign alliance and creating a new, permanent government for the nation.4

Not everyone was pleased with the final resolution. George Mason called it “tedious, rather timid, & in many Instances exceptionable; but I hope it may answer the Purpose.”5 Thomas Ludwell Lee wrote that the preamble was “not to be admired in point of composition,” but nevertheless gave “infinite joy” to the people. In Williamsburg, he wrote, the “exultation . . . was extreme.” The British flag from the Capitol’s cupola was swapped for a continental flag, and local troops fired artillery and small arms.6 According to the Virginia Gazette, celebrations ended “with illuminations, and other demonstrations of joy; every one seeming pleased that the domination of Great Britain was now at an end.”7

The Williamsburg convention’s instruction to its delegates led Richard Henry Lee to make the first formal motion for American independence on June 7, 1776. This led to the appointment of a committee, which included Virginian Thomas Jefferson, to draft the document that inscribed the principles of equality and liberty onto the moment of American independence.

Why It Matters

Alongside this was another resolution creating a committee to prepare a declaration of rights and a plan of government for the new state of Virginia. Passed on the same day that the Continental Congress called for state governments to begin forming their own constitutions (though Virginians didn’t know this yet), the resolutions of May 15 constituted their own kind of declaration of independence. Like many other colonies, counties, and localities, Virginia had taken its own steps toward independence.

Today, we remember July 4, 1776, the day that the Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence, as the moment that the United States began. But the decision to seek independence was not made that day. It was made many times, in many places, in the months before July 4.8 One of those places was Williamsburg on May 15, 1776, when the leaders of the largest and most powerful colony rejected the authority of Britain, the world’s most powerful empire, which had ruled this land for generations. This bold act did not determine an outcome. There was much maneuvering and finessing yet to be done in Philadelphia. And there was still a war to be won. But the independence resolution made in Williamsburg set Americans on their journey toward independence.

Sources

- On the context leading up to independence, see Pauline Maier, American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence (Knopf, 1997), ch. 1; Michael A. McDonnell, The Politics of War: Race, Class, and Conflict in Revolutionary Virginia (Omohundro Institute for Early American History and Culture, 2007), ch. 6.

- Edmund Randolph, History of Virginia, ed. Arthur H. Shaffer (University Press of Virginia, 1970), 234.

- Brent Tarter and Robert L. Scribner, eds., Revolutionary Virginia: The Road to Independence vol. 7 (University Press of Virginia, 1983), 145–46.

- Tarter and Scribner, eds., Revolutionary Virginia, 7:142–43.

- Robert A. Rutland, ed., The Papers of George Mason, 1725-1792, vol. 1 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1970), 270.

- ”Selections and Excerpts from the Lee Papers,” Southern Literary Messenger 27, no. 5 (November 1858), 324-325;

- Virginia Gazette (Purdie), May 17, 1776, p. 3, link.

- Maier, American Scripture