Thomas Paine's Common Sense

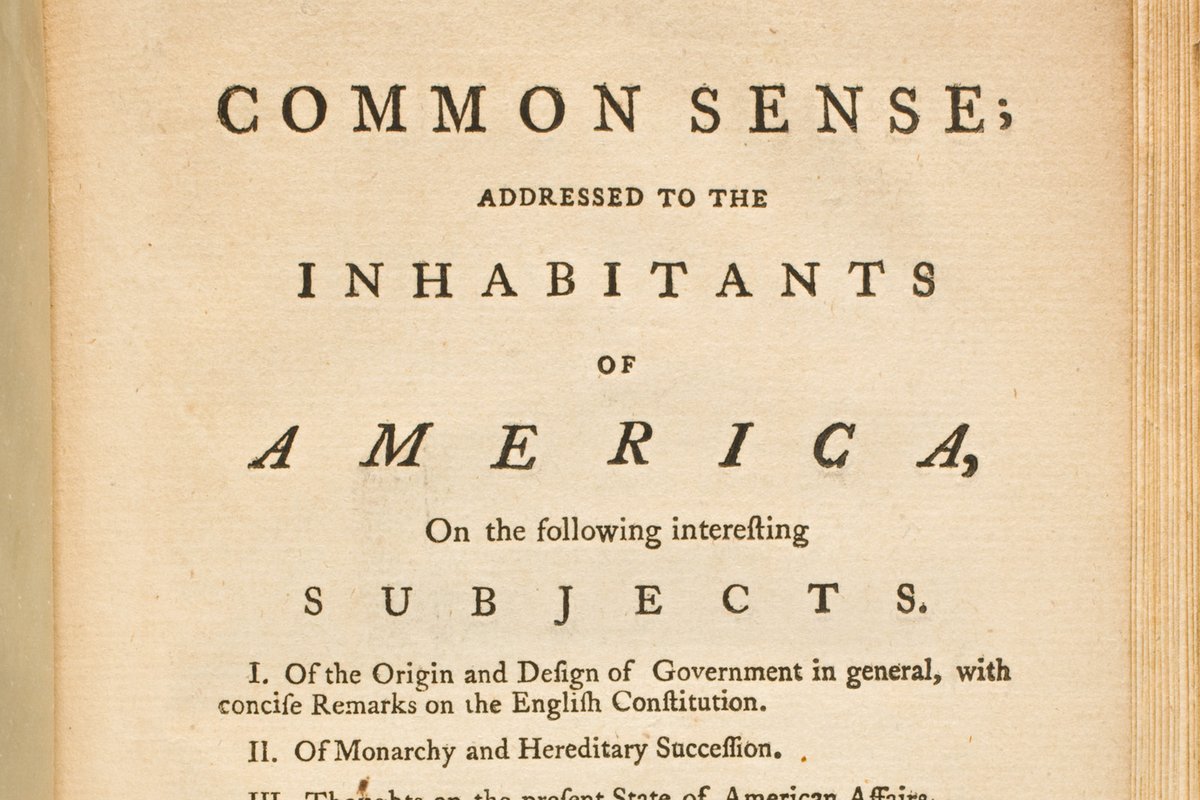

The most important pamphlet in revolutionary America, Thomas Paine’s Common Sense was an unlikely hit. It was written by an unknown recent immigrant, for an audience that seldom purchased or read pamphlets. Yet Paine’s clear, direct language connected with readers across the continent. It was published on January 10, 1776, a time when violence had broken out between the colonists and Britain, but many remained uncertain about what the conflict meant. Common Sense helped to convince many wavering colonists to join the fight for independence. As Paine wrote, “We have it in our power to begin the world over again.” And so they did.

Why It Matters

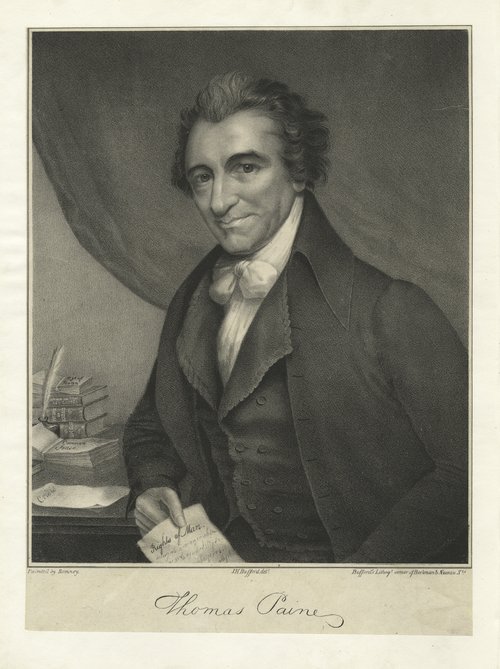

Thomas Paine (1737–1809). Image courtesy of New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Common Sense is widely credited with pushing colonists toward independence. Paine wrote that it was “very absurd” for “a Continent to be perpetually governed by an island.” He excelled at transforming complex ideas into clear expressions. At a time when many political texts indulged in long quotations from obscure sources, Paine put the matter plainly. He explained, “the more simple any thing is, the less liable it is to be disordered.”

As a result, he connected with a larger audience of readers than any other political writer of his day. General George Washington reported that in Virginia, “common sense is working a powerful change there in the Minds of many Men."1 Not everyone was impressed. In Loudon County, Virginia, the British diarist Nicholas Cresswell commented, “A pamphlet called ‘Commonsense’ makes a great noise. One of the vilest things that ever was published to the world.”2

Most historians agree that Common Sense played an important role in bringing about American independence. But probably only a small portion of the population read it. Though it would have been available from booksellers, it was not republished in Virginia during the revolution. However, portions did appear in the Williamsburg Virginia Gazette.

Ideas

[T]he more simple any thing is, the less liable it is to be disordered.

— Thomas Paine, Common Sense

Common Sense is remembered today not only for its role in igniting American independence, but also because its words reflect some of the revolution’s highest aspirations and central ideas. For Paine, government existed to secure the happiness and safety of the people by restraining their vices. Good government could only happen with a “frequent interchange” between voters and representatives. Whatever monarchists or aristocrats may claim that the hierarchies they stood atop were natural and essential, Paine wrote, “the simple voice of nature and of reason will say, it is right” that people should govern themselves. At a time when many elite British colonists praised the aristocratic or monarchical elements of the British government, Paine rejected them outright.

Following his examination of the nature of government and his attack on monarchy, Paine built a case for immediately acting to secure American independence. And he offered some thoughts about what the new nation’s government should look like. Above all, he concluded, “in free countries the law ought to be King.”

It was an optimistic vision, imagining the United States as a place where natural rights could be secured in a land untethered by centuries of tyranny. He wrote, “we have every opportunity and every encouragement before us, to form the noblest purest constitution on the face of the earth. We have it in our power to begin the world over again. A situation, similar to the present, hath not happened since the days of Noah until now. The birthday of a new world is at hand…”

A government of our own is our natural right.

— Thomas Paine

Learn More

How a London Printer Censored the World's Most Dangerous Pamphlet

“Common Sense” went viral in 1776. Its simple language attacking the king helped push public opinion toward independence—but it also made printing it dangerous. Librarian Doug Mayo shows how one London printer censored Thomas Paine’s pamphlet to protect himself.

Sources

- “George Washington to Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Reed, 1 April 1776,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-04-02-0009.

- Nicholas Cresswell, The Journal of Nicholas Cresswell, 1774–1777 (Dial Press, 1924), 136.