The Virginia Declaration of Rights

Virginia’s Declaration of Rights, passed by the Fifth Virginia Convention in the Williamsburg Capitol on June 12, 1776, is one of the most important documents that many Americans have never heard of. Its primary author George Mason laid down the highest principles of the American revolutionary movement in ways that would soon be imitated in the Declaration of Independence, Constitution, Bill of Rights, and more. Its clauses teach us not only about the aspirations of the revolutionary generation, but also about the tensions within Virginia society over slavery, religion, and the question of equality.

Mason’s Draft

In May 1776, an elected convention of Virginia leaders met in Williamsburg. On the ninth day of deliberations, the Fifth Virginia Convention, as it is now known, unanimously made two fateful decisions. First, it instructed Virginia’s delegates to the Continental Congress to “declare the United Colonies free and independent states.” And second, they resolved that “a Committee ought to prepare a Declaration of Rights” and a “plan of government.”1

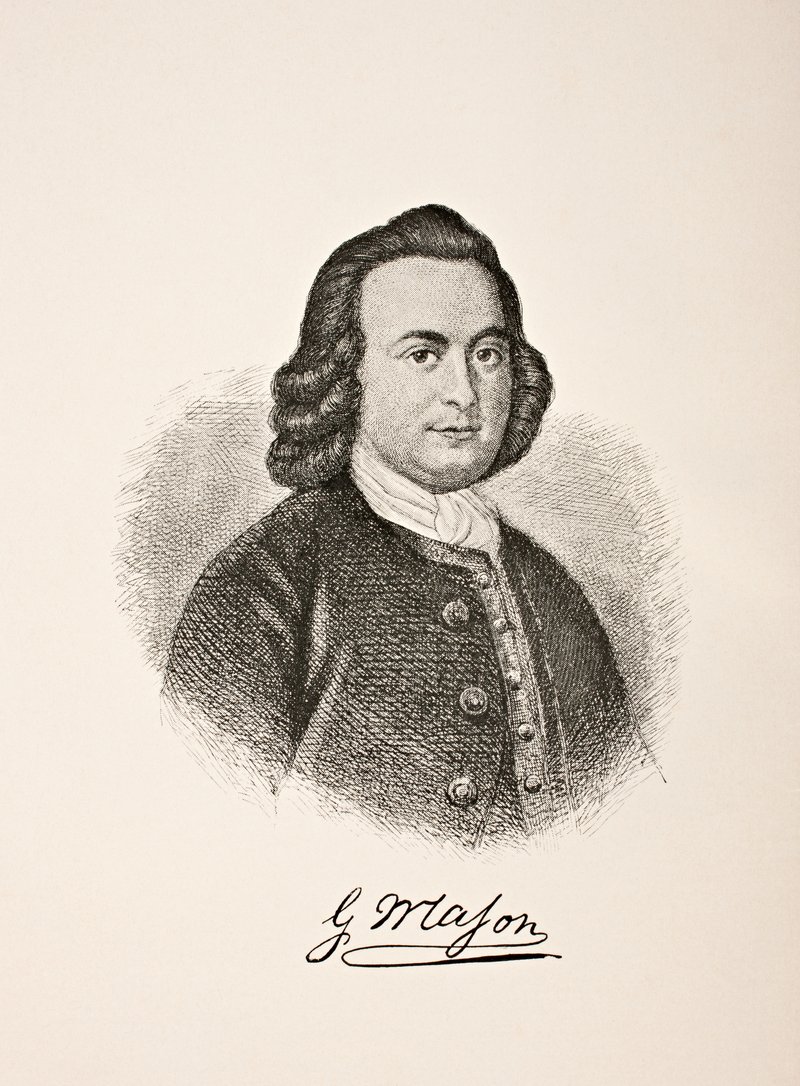

Fronticepiece portrait of George Mason from Kate Mason Rowlands The Life of George Mason. New York: GP Putnams Sons, 1892. vol. 1

George Mason, one of Virginia’s most respected political thinkers, arrived late to the convention on account of illness. But when he arrived, he was quickly appointed to the committee to draft these documents, and took charge of the process. He wrote the first draft of the Declaration of Rights, with some input from Thomas Ludwell Lee. While the larger committee made numerous edits, the final document was more the product of Mason’s pen than anyone else.

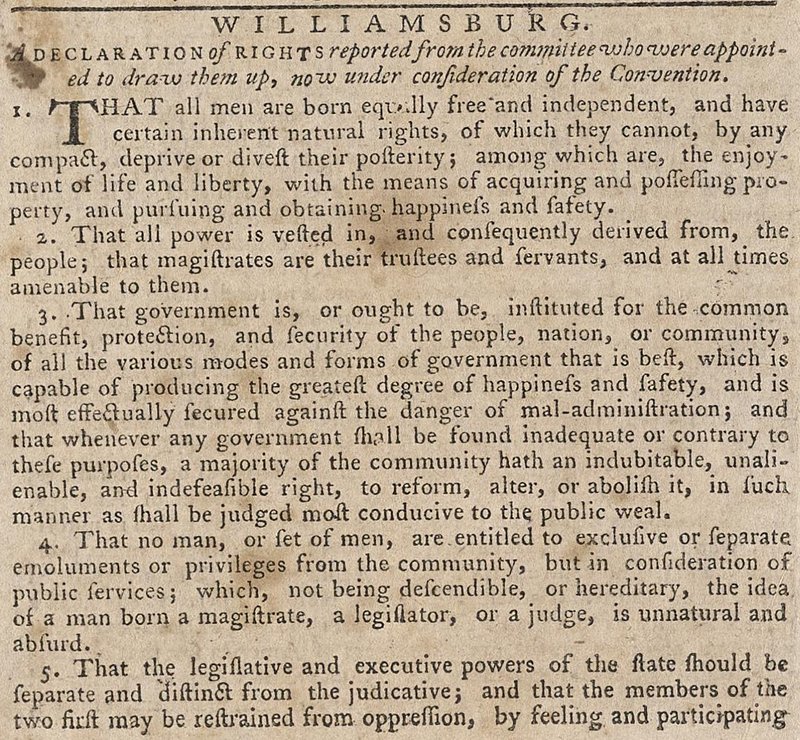

Mason’s unedited draft was published in the Virginia Gazette before the convention agreed on a final version. Virginia Gazette (Dixon and Hunter), June 1, 1776, p. 2. Find the full article in Colonial Williamsburg’s Digital Collections.

Slavery and Society

The first meaningful words in the Declaration of Rights were among the most controversial of the convention. After Mason’s draft was introduced for debate, delegate Robert Carter Nicholas objected to the opening clause, “That all Men are born equally free and independant.” If “all Men” were free, did that include enslaved men? In a slave society, might such language be understood to effectively abolish slavery?2

This point weighed heavily on the convention. They did not want to discard the document’s commitment to natural rights, which was so central to revolutionary ideologies. But they were also unwilling to allow anything that could challenge Virginia’s system of slavery. Eventually, Edmund Pendleton found a compromise. After a few days of debate, he proposed that the convention add a qualification. The document continued to assert that men were born free and equal, but now the convention claimed that these rights were only passed on by men “when they enter into a state of society.”3 This addition, which the convention accepted, was understood to exclude enslaved people from the document’s expansive promises of natural rights.

While Virginians often avoided confronting the contradiction of slavery and revolution in their society, the tensions at the heart of the Declaration of Rights made it unavoidable. Thirty years after the Fifth Virginia Convention, Virginian George Wythe (who was not present at that meeting) put this clause to the test. In the 1806 case Hudgins v. Wright, Chancellor Wythe ruled in favor of an enslaved family suing for freedom based on their Native heritage (since Virginia law outlawed the enslavement of Indigenous people). But he added a second justification: the language of universal equality in the 1776 Declaration of Rights already recognized this family’s freedom.4 Virginia’s Court of Appeals affirmed Wythe’s overall decision but took care to challenge his interpretation of the Declaration of Rights. St. George Tucker, one of the appeal court’s judges, commented that the Declaration of Rights had been “framed with a cautious eye to this subject, and was meant to embrace the case of free citizens, or aliens only; and not by a side wind to overturn the rights of property.”5

Religious Liberty

The fourteenth article of Mason’s draft promised the “fullest Toleration” of religion, unless a religious practice should “disturb the Peace, the Happiness, or Safety of Society.” Compared to many governments around the world, this was a robust conception of religious liberty for its time. It mirrored longstanding protections in England. But some reformist members of the convention wanted to push toward the next frontier: a more affirmative right to religious equality, and perhaps an end to an officially established state religion.

James Madison maneuvered behind the scenes to include a provision in the Declaration of Rights that would have likely ended government funding for the Church of England—an outcome known as disestablishment.6 He convinced Patrick Henry to support it, but Henry turned against the provision in the face of opposition. Eventually, Madison and Edmund Pendleton worked together to pass what became the sixteenth and final article of the Declaration of Rights: “all men are equally entitled to the free exercise of religion, according to the dictates of conscience; and that it is the mutual duty of all to practise Christian forbearance, love, and charity toward each other.”7

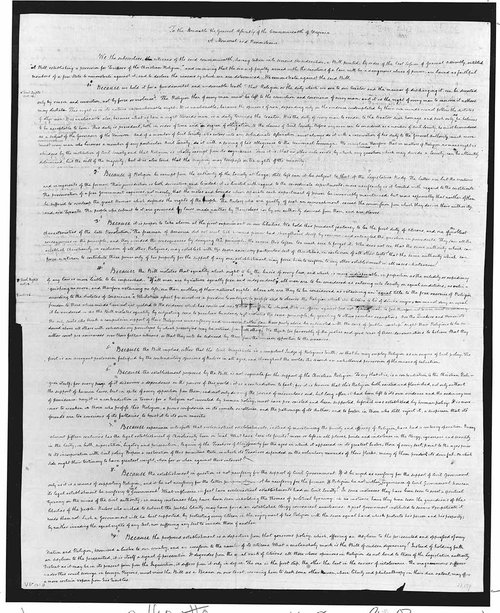

James Madison’s manuscript draft of A Memorial and Remonstrance against Religious Assessments. Library of Congress.

While the Declaration of Rights did not directly lead to the disestablishment of the Church of England (or Anglicanism) in Virginia, it did provide a basis for future challenge. In 1783, Madison wrote a pamphlet arguing for a stronger separation of church and state. He quoted the Declaration of Rights’ opening promise that “all men are by nature equally free and independent,” and the closing clause (which he had written) promising “equal title to the free exercise of Religion according to the dictates of Conscience.” Using this authority, Madison suggested that there could be no true religious equality with a state-established faith.8

Madison continued to use the Declaration of Rights as the basis for his thinking about religious liberty. Years later, when he authored the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, he used the same language as the Declaration of Rights’ sixteenth clause, prohibiting government interference in the “free exercise” of religion.

Revolutionary Ideas

The Virginia Declaration of Rights distilled many of the era’s key revolutionary ideas, as well as significant parts of Anglo-American law and Enlightenment philosophy. Mason and its other framers drew on precedents contained in documents such as Britain’s Magna Carta of 1215, the English Bill of Rights of 1689, and statements of rights within the colonial charters of New York, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts. Early bills of rights often lacked the legal language of the constitutions or charters they accompanied. Rather, they were designed to identify broad principles that the structure of the constitutions would put into practice.9

The Virginia Declaration of Rights listed numerous principles that revolutionaries generally agreed on: that government rested on the consent of the governed, separation of powers, regular elections, term limits, no taxation without representation, religious liberty, freedom of the press, no standing armies during peacetime, and civilian control of the military. It created protections for civil liberties and due process of the law. The Declaration protected the rights to trial by jury, to face accusers, and to avoid self-incrimination. It also placed limits on search and seizure, fines, and “cruel and unusual punishments.” Many of these elements, and often some of the same phrasing, later appeared in the U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights.

In Philadelphia, Thomas Jefferson wrote the U.S. Declaration of Independence in the weeks following the publication of Mason’s draft of the Declaration of Rights. It is likely that Jefferson had a copy of Mason’s work at his side as he wrote. Anyone reading the two documents alongside each other can detect similar themes such as natural rights and the right to revolution. The language is very similar in some places. Where Mason asserted that “men are by nature equally free and independent,” Jefferson wrote “all men are created equal & independent,” later revised to “all men are created equal.” Where Mason argued that mankind had a right to “the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety,” Jefferson put it plainly: government should protect peoples’ “life, & liberty, & the pursuit of happiness.” Though little acknowledged today, historians agree that the Virginia Declaration of Rights was one of the central influences on the preamble of the Declaration of Independence.

Why It Matters

In the final week of the Philadelphia Constitutional Convention in 1787, according to James Madison, delegate George Mason complained about the proposed constitution’s lack of a bill of rights: “He wished the plan had been prefaced with a Bill of Rights, & would second a Motion if made for the purpose. It would give great quiet to the people; and with the aid of the State declarations, a bill might be prepared in a few hours.”10 Perhaps he imagined that, as so many other writers had done, they would start by consulting the Declaration of Rights he had drafted for Virginia. But the exhausted Convention went home without adding a bill of rights. Mason refused to support the Constitution, in part because of this absence.

Virginia’s was the first state to adopt a statement of rights as part of its new revolutionary constitution. Subsequently, many other states prefaced their constitutions with a list of rights, leading some Americans to expect this in the proposed constitution. Still, Madison and other supporters of the constitution argued that imprecise statements of principle could offer nothing more than “parchment barriers” against misrule.11

Yet for many, even an imperfect, incomplete bill of rights was important to signal the intention of a government. As one Virginian wrote, a bill of rights would provide a basis for future “asserters of liberty” to “rally, and constitutionally defend” the document’s ideals.12 Opponents of the constitution successfully pressed for the addition of a bill of rights, which resulted in the first ten amendments to the U.S. Constitution. In this way, the United States Bill of Rights has its origin, in part, in the tradition that the Virginia Declaration of Rights helped to build.

Today, the Virginia Declaration of Rights carries the force of law within the state. In 1830, a new state constitution incorporated it as the document’s first article. Yet its importance extends far beyond Virginia’s borders. Two-and-a-half centuries later, it remains a tool for Americans to “rally, and constitutionally defend” the doctrines of civil liberties, natural rights, and human equality.

Sources

- Revolutionary Virginia: The Road to Independence, vol. 7, pt. 2: Independence and the Fifth Convention, 1776, ed Brent Tarter and Robert L. Scribner (University Press of Virginia, 1983), 143.

- Jeff Broadwater, George Mason: Forgotten Founder (University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 84.

- Robert A. Rutland, ed., The Papers of George Mason, 1725–1792: vol. 1: 1749–1778 (Chapel Hill, 1970), 275; Revolutionary Virginia, ed. Tarter and Scribner, Vol. 7 pt 2, 454.

- William M. Wiecek, The Source of Anti-Slavery Constitutionalism in America, 1760–1848 (Cornell University Press, 1977), 52.

- Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia, v. 1, ed. William W. Hening and William Munford (Riley, 1809), 140, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433009476502&seq=179.

- “Madison’s Amendments to the Declaration of Rights, [29 May–12 June 1776],” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/01-01-02-0054-0003.

- Broadwater, George Mason, 85–87.

- “Memorial and Remonstrance against Religious Assessments, [ca. 20 June] 1785,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/01-08-02-0163; John Ragosta, Religious Freedom: Jefferson’s Legacy, America’s Creed (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2013), 88–89.

- Jonathan Gienapp, The Second Creation: Fixing the American Constitution in the Founding Era (Harvard University Press, 2018), 51.

- The Writings of James Madison, vol. 4: 1787 (G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1903), 442.

- The Federalist, no. 48, in New-York Packet, Feb. 1, 1788.

- Gienapp, Second Creation, 98 (quote).