The Virginia Constitution of 1776

The Virginia Constitution, adopted on June 29, 1776, was one of the earliest written constitutions in the western world.1 In its pages, Virginians designed a constitutional structure that reflected many of their longstanding beliefs about government and human nature.

Crafted in Williamsburg’s Capitol as the colony stood on the precipice of independence, Virginia’s revolutionary constitution marked the culmination of more than a decade of political agitation. It was one beginning, among many, in which Americans began the long process of working out how they would govern themselves.

How It Was Written

On May 15, 1776, the Continental Congress, an intercolonial revolutionary body, called for states the adopt their own constitutions. Afterward, Massachusetts delegate John Adams, who authored the resolution, explained to a fellow member of Congress with a smile that this resolution was “independence itself”—and all that was left was the “formality.”2 The creation of new state constitutions was a point of no return.

As was often the case in the revolutionary era, Virginians were ahead of their neighbors. Even as the Continental Congress was passing this resolution, Virginians were meeting to decide a path forward in a post-independence era. For nearly two years, Virginians had been governing themselves through local committees and a series of elected conventions. In 1776, many of the leading figures in Virginia’s aristocratic gentry met for the Fifth Virginia Convention in Williamsburg’s Capitol, including Edmund Pendleton, George Mason, Patrick Henry, Robert Carter Nicholas, George Wythe, James Madison, and Edmund Randolph.

Since Virginia was the most populous and powerful British North American colony, its constitution would set the tone for others.3 The stakes were high. According to Virginian Richard Henry Lee, “Ages yet unborn, and millions existing at present, must rue or bless that Assembley, on which their happiness or misery . . . depend.”4 People from across the colonies sent their ideas to Williamsburg, hoping to shape the constitution. Delegates to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia, including Carter Braxton, Richard Henry Lee, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson, sent letters and pamphlets to Virginia, hoping to shape the constitution-making process from afar.

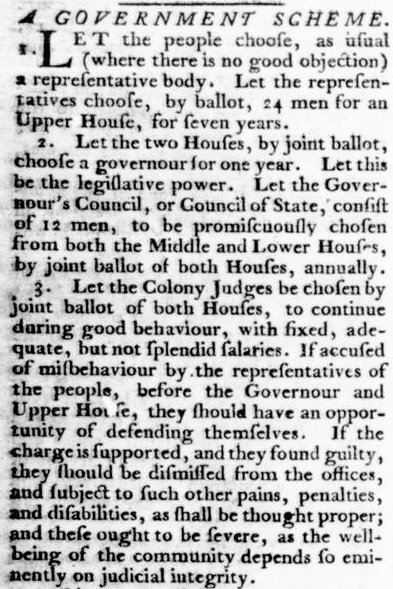

A handbill written by Richard Henry Lee, drawing on many of John Adams’ ideas, was printed in the Virginia Gazette as the Fifth Convention met. Virginia Gazette (Purdie), May 10, 1776, p. 4. Find the full article in Colonial Williamsburg’s Digital Collections.

On the day the Continental Congress called for states to make their own constitutions, the Williamsburg convention made two momentous decisions. First, they instructed their delegates to the Continental Congress to propose independence. And second, they appointed a committee to write a new constitution and declaration of rights for the state. While New Hampshire and South Carolina had created provisional constitutions, meant to operate for the duration of the conflict with Britain, Virginians were the first American colonists to create a permanent, written constitution on their own authority.5

When George Mason, who had been ill, arrived late to the convention, he was appointed to the committee to draft these documents.6 Mason quickly took charge. Though not trained as a lawyer, he was widely regarded in the state as one of its leading political thinkers. Expecting a “thousand ridiculous and impracticable proposals” from the committee’s “useless Members,” Mason took on the task of drafting both documents himself.7

After much wrangling and editing, the committee produced a constitution, which the convention debated and eventually approved. On June 29, 1776, Virginia had a new system of government. On the same day that they passed the constitution, the Williamsburg convention put it into practice. They chose Patrick Henry as the state’s first elected governor.

…the government of this country, as formerly exercised under the crown of Great Britain, is TOTALLY DISSOLVED.

— Virginia Constitution of 1776

Why It Matters

The Constitution adopted by the Convention was prefaced with a Declaration of Rights, which Mason also authored. It included a lengthy list of grievances against Britain’s King George III, taken from Thomas Jefferson’s draft constitution that he sent from Philadelphia to Williamsburg. Though his draft arrived too late to affect the much of the constitution’s design, delegates agreed to adopt Jefferson’s list of grievances. Many of them would soon reappear in his draft of the Declaration of Independence.8

The structure of the 1776 constitution reflected the predominant political and legal wisdom of the day. It left voter qualifications unchanged. It created separate executive, judicial, and legislative branches of government: a governor, Council, court system, and a General Assembly including a House of Delegates and a Senate. These largely mirrored colonial institutions. Yet while the colonial governor, as the voice of the king, held significant sway in colonial Virginia, Virginia’s first elected governors would be fairly weak. Instead, like many other colonies, Virginia chose to strengthen the legislature, in hopes that it would reflect the wisdom and genius of the people.9

Any Virginians hoping for a radical upheaval of their system of government would have been disappointed. Richard Henry Lee had earlier argued that they could create a government that was “nearly the form we have been used to.”10 If this was the goal of the Fifth Virginia Convention, they succeeded. In a sense, then, the 1776 Virginia Constitution changed little within Virginia. The new constitution maintained many elements of the system that had governed colonial Virginia for more than a century. By maintaining much of the status quo, this constitution helped to protect the existing strength of Virginia’s wealthy, elite planters in the state’s politics.11

Key Ideas

The Virginia Constitution of 1776 was one of the earliest examples in the young United States of a written document created by a people to define the shape and boundaries of their own government. At its heart was a commitment to written constitutionalism. This was more radical at the time than it may appear today. The English constitution, as it was understood at the time, was not a single written document, but rather a broad institutional consensus shaped by an accumulation of meaningful documents and decisions starting with the Magna Carta.12 The Virginia Constitution left this tradition behind. It announced that Virginia’s governor “shall not, under any pretence, exercise any power or prerogative, by virtue of any law, statute or custom of England.” Instead, the government’s powers would be fixed in a single written document and grounded in the express consent of the people it governed.

The Virginia Constitution embodied another key insight emerging in 1776: a powerful executive was dangerous to liberty. Recent experience, reflected in the document’s preface listing King George III’s transgressions, seemed to prove this. And so Virginia’s Constitution created an intentionally weak executive, with a three-year term that did not permit immediate re-election.

Having experienced irritating dissolutions of the House of Burgesses in the recent past, they also pointedly denied the governor the right to adjourn, prorogue, or dissolve the assembly.13

As they wrote their own constitutions, most other colonies embraced this model of a weak executive. But in subsequent years, many American political leaders came to regard this as a mistake. In his Notes on the State of Virginia, Thomas Jefferson complained that the Virginia constitution was written “when we were new and unexperienced, in the science of government,” which caused it to include many errors, creating “an elective despotism.”14 A few years later, the advocates of the new U.S. Constitution framed their efforts, in part, as an attempt to rebalance government and tame the supremacy of the legislative branch. In 1788, James Madison quoted Jefferson’s indictment of the Virginia constitution in “The Federalist,” a series of pro-Constitution essays, as he argued that across the nation, the legislative branch was “drawing all power into its impetuous vortex.”15 The apparent flaws of state constitutions like Virginia’s became an important impetus for the creation of the U.S. Constitution in 1787.

Excerpts

Sources

- Willi Paul Adams, The First American Constitutions: Republican Ideology and the Making of the State Constitutions in the Revolutionary Era (Lanham, 2001), 3.

- “[Wednesday May 15. 1776] ,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/01-03-02-0016-0120.

- Adams, First American Constitutions, 55, 72–73, 82,

- Richard Henry Lee to Patrick Henry, April 20, 1776, in James Curtis Ballagh, ed., The Letters of Richard Henry Lee (New York: The MacMillan Company, 1911), 1:176.

- Willi Paul Adams, The First American Constitutions: Republican Ideology and the Making of the State Constitutions in the Revolutionary Era (University of North Carolina Press, 1980), 5.

- Jeff Broadwater, George Mason: Forgotten Founder (University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 80.

- Broadwater, George Mason, 80–81.

- Broadwater, George Mason, 96.

- Broadwater, George Mason, 92.

- John E. Selby, “Richard Henry Lee, John Adams, and the Virginia Constitution of 1776,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 84 (Oct. 1976): 387–400, quote on 396.

- Kevin R. C. Gutzman, Virginia’s American Revolution: From Dominion to Republic, 1776–1840 (Lanham, 2007), 7.

- Jonathan Gienapp, The Second Creation: Fixing the American Constitution in the Founding Era (Harvard University Press, 2018), 27.

- Revolutionary Virginia: The Road to Independence, vol. 7, pt. 2: Independence and the Fifth Convention, 1776, ed Brent Tarter and Robert L. Scribner (University Press of Virginia, 1983), 652.

- Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia. With an Appendix (H. Sprague, 1802), 162, 164, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Jefferson_s_Notes_on_the_State_of_Virgin/B0maYXhKDpgC?hl=en&gbpv=1.

- Federalist no. 48, in New-York Packet, Feb. 1, 1788.