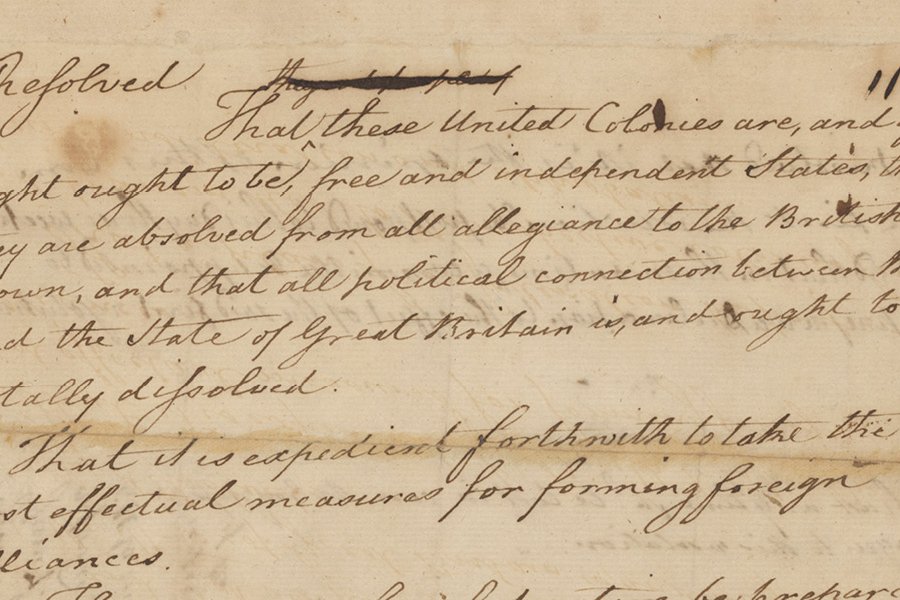

The Lee Resolution

On June 7, 1776, Virginia delegate Richard Henry Lee rose on the floor of the Second Continental Congress. Leaders from across British North America had gathered in Philadelphia to coordinate their colonies’ response to the escalating imperial crisis between themselves and Great Britain. Though violence had already broken out, many colonists continued to believe that they could still reconcile with Britain. It was not until Lee’s motion that the full Congress began to seriously consider, and take steps toward, separation from Britain.

Virginia at the Vanguard

In 1822, an aging John Adams made an astonishing confession. In a letter to Timothy Pickering, his former secretary of state, Adams described a secret meeting in 1774 in the days before the first meeting of the Continental Congress. As they arrived in Philadelphia, the Massachusetts delegation, including Adams, was intercepted by the Pennsylvania delegation and taken to a small town called Frankford for a private strategy meeting.1

John Adams (1735–1826). Courtesy of New York Public Library Digital Collections.

They agreed that the Massachusetts delegation, which had earned a reputation as “desperate adventurers,” would step back, and remain as quiet as possible during the congress, to avoid scaring any others delegations. Noting that independence was unpopular outside of New England, the Pennsylvanians admonished the Massachusetts men, “you must not utter the word Independence, nor give the least hint or insinuation of the idea, neither in Congress or any private conversation; if you do you are undone.” They further told him that because Virginia was the most populous colony, “They are very proud of their antient Dominion, as they call it; they think they have a right to take the lead, and the Southern States and middle States too, are too much disposed to yield it to them.”2

The “wisdom” of this strategy was obvious to Adams, who realized in retrospect that it had given the “colour complection and character to the whole policy of the United States, from that day to this. Without it, Mr: Washington would never have commanded our armies, nor Mr: Jefferson have been the Author of the declaration of Independence, nor Mr: Richard Henry Lee the mover of it.”3 The other colonies allowed and expected Virginians to take the lead. The creation of the United States would be set by Virginia’s pace.

The Resolution

By the middle of 1776, a coalition of American colonists had been fighting a war against Britain for nearly a year without having officially declared independence. This frustrated many, who worried about fighting a war without being able to make foreign alliances. Yet there was no consensus. Many states remained cautious, avoiding a commitment until popular sentiment began to move decisively toward independence. That began to happen in the first half of 1776, as Thomas Paine’s Common Sense pushed many colonists to consider independence. Months earlier, leaving the British empire had been unthinkable. Suddenly it seemed self-evident.

On May 15, 1776, an elected convention of Virginia leaders meeting in Williamsburg’s Capitol voted to instruct the colony’s delegates to the Continental Congress to propose American independence. News of these resolutions quickly arrived in Philadelphia. The Williamsburg convention’s resolutions were read in Congress on May 27, but the Congress did not begin consideration of the matter immediately.4

The Continental Congress’s journals indicate that Richard Henry Lee introduced his resolution for American independence on June 7, immediately following consideration of a complaint about defective gunpowder coming from a mill in Frankford, Pennsylvania—the same town where Massachusetts and Pennsylvania had once agreed to let Virginia take the lead. It was an appropriate introduction to an explosive motion.5

The Debate

Lee’s resolution included the three key points of Virginia’s May 15 resolutions: that the colonies should be independent, that they should seek foreign alliances, and that they should form a new government for their confederation. But Lee’s resolution also differed in subtle ways from his instructions. It lacked the initial instructions’ proviso that the new confederation would not regulate the “internal concerns” of the states. And it lacked any kind of preface, such as the one included with the May 15 resolutions, which often accompanied momentous resolves to explain the decision. Lee’s resolution was simple and straightforward, lacking the lengthy preface Virginia’s leaders had included in their instructions. Though Patrick Henry and others deemed the language used in the May 15 resolutions to be too tame, they might have seemed too aggressive for the wavering delegations.6

Yet many members of the Continental Congress remained hesitant. Some were willing to support independence, but had not received instructions from their state legislatures that would allow them to vote for it. Congress decided to stall. According to Jefferson, delegates from the middle colonies asked for time. They wanted to respond to “the voice of the people,” and thought that while their colonies were “not yet ripe for bidding adieu to British connection but that they were fast ripening.” A delay would allow their legislatures time to consider the issue and send their delegates instructions.7 While they tabled the official vote, Congress prepared for independence. They appointed a committee to draft the declaration. Much like the Lee resolution, and Washington’s appointment as commander-in-chief of the army, the role of principal author of the Declaration of Independence would go to a Virginian, the young Thomas Jefferson.

Why It Matters

In the summer of 1776, it must have seemed that everything was happening at once. Battles were being fought, Congress was in session, and state legislatures and conventions were meeting across the colonies. Days after the independence resolution was introduced, Richard Henry Lee and George Wythe departed Philadelphia for Williamsburg, hoping to return in time to participate in deliberations about the creation of Virginia’s new government. Jefferson wished he could be back in Williamsburg, but the absence of the more senior members of his delegation compelled him to remain—one reason why he authored the Declaration of Independence.8

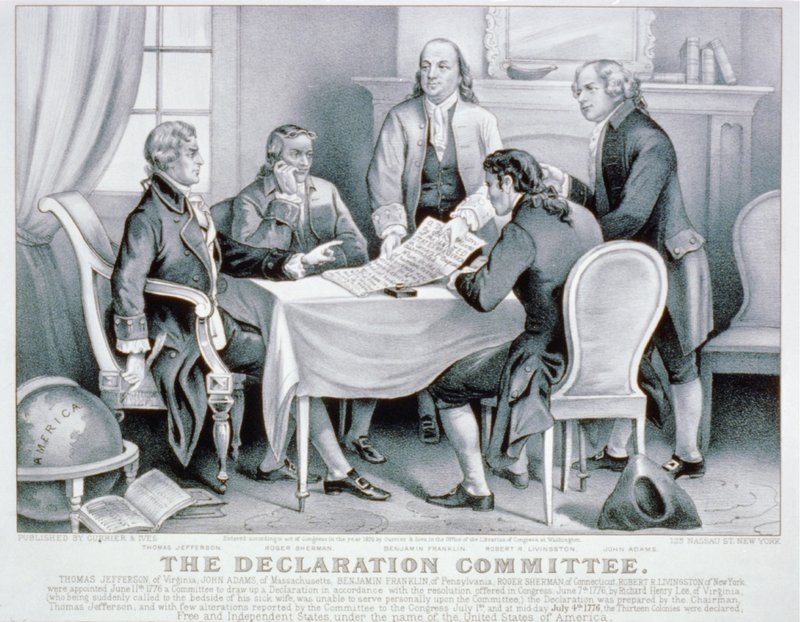

Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

But Jefferson and others in Philadelphia still sent ideas to Williamsburg. Jefferson’s list of grievances against the king appeared in the Virginia Constitution, before a very similar list appeared in the Declaration of Independence. And documents drafted in Williamsburg shaped the texts drafted in Philadelphia. A draft of George Mason’s Declaration of Rights was perhaps the most important single influence on the preamble of Jefferson’s draft of the Declaration of Independence. The Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia and the Fifth Virginia Convention in Williamsburg were engaged in a complex exchange of ideas and words. The Lee Resolution is perhaps the most important example of this interchange, exemplifying the longstanding leadership of Virginia in the drive for American independence.

Sources

Cover image courtesy of the National Archives.

- See “1774 Aug. 29. Monday.,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/01-02-02-0004-0005-0017.

- “From John Adams to Timothy Pickering, 6 August 1822,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/99-02-02-7674.

- “From John Adams to Timothy Pickering, 6 August 1822.”

- “Resolutions of the Virginia Convention Calling for Independence, 15 May 1776,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-01-02-0152.

- Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789, vol. 5: 1776, June 5–October 8 (Government Printing Office, 1906), 425, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Journals_of_the_Continental_Congress/ujQSAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PA425&printsec=frontcover.

- William Wirt Henry, Patrick Henry: Life, Correspondence and Speeches, vol. 1 (New York: Burt Franklin, 1969), 412.

- “Notes of Proceedings in the Continental Congress, 7 June–1 August 1776,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-01-02-0160.

- Pauline Maier, American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence (Knopf, 1997), 47–48.