Sezor Phelps to Charles Phelps, Jr.

There are a total of two surviving letters by African American soldiers in the Continental Army. A letter by Sezor Phelps to his enslaver Charles Phelps Jr. is one such letter. Born around 1752, there is little information about Sezor. We know he was bought by Charles in 1770 for about 66 pounds. He lived and worked on Charles’s farm in Hadley, Massachusetts, called Forty Acres. At some point, Sezor lost use of one of his hands, perhaps from some sort of accident. The disability, however, didn’t stop Sezor from being accepted into the army, a somewhat surprising fact.

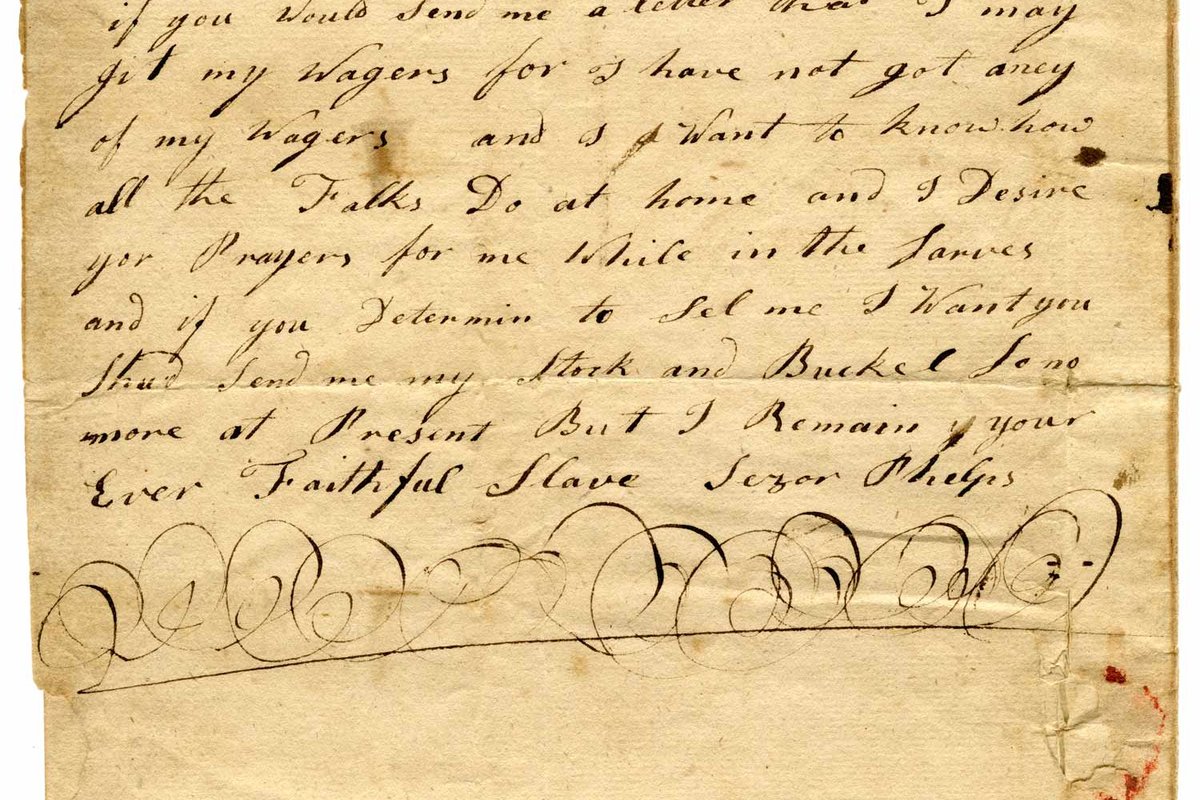

At 24 years old, Sezor was serving as his enslavers substitute in the Massachusetts militia. Written from Fort Ticonderoga, the letter from Sezor to Charles is short and to the point. Sezor’s letter discusses his potential wages, requests news from home, and acknowledges that Charles was considering selling him. Unfortunately, this letter is the last source we have on Sezor’s life. What his fate was in the war, or whether he was sold by Charles, and much more, remain a mystery.1

Sezor Phelps to Charles Phelps, Jr.

Camp Ticontoroga Sept the 30th 1776

Sir I take this oppertunity to Enform you that I dont Entend to Live With Capt Cranston if I can help it and I would Be glad if you Would send me a letter that I may git my Wagers for I have not got aney of my Wagers and I want to know how all the Folks Do at home and I desire yor Prayers for me While in the the Sarves and if you Determine to sel me I Want you Shud send me my Stock and Buckel so no more at Present But I Remain your Ever Faithful Slave Sezor Phelps

Black Americans and the American Revolution

By the time of the American Revolution, there was a sizable Black population in the colonies. Black Americans were involved in several ways, and witnessing the revolution around them was just one such way.

As witnesses to a unique time in history, Black Americans offered their own opinions and observations of the events around them. For some, this proved crucial in finding and fighting for freedom. For others, this meant they could contribute their own opinions to the chorus of revolutionary-era rhetoric.

Sources

- James G. Basker and Nicole Seary, eds., Black Writers of the Founding Era, 1761-1800 (Library of America, 2023), 151.