Petition of Bristol Lambee to the Connecticut Sons of Liberty

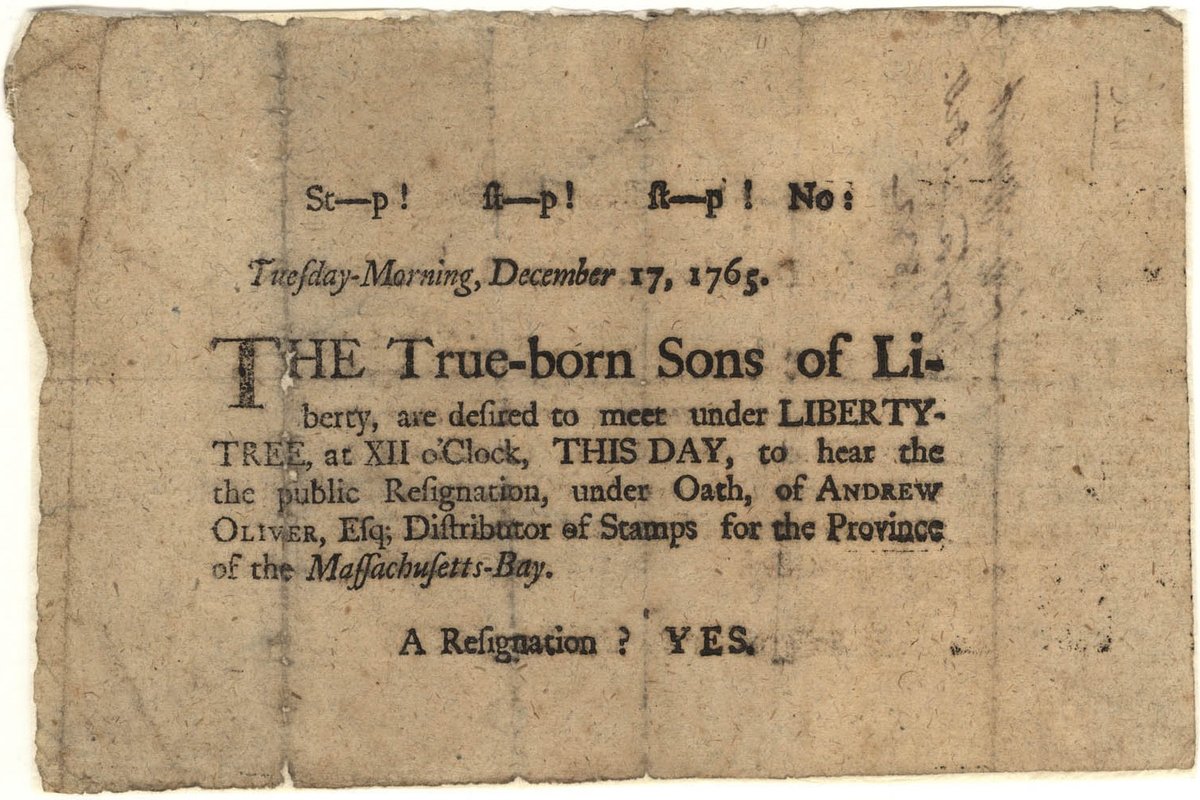

This petition from Bristol Lambee, (sometimes spelled Bristo), was the first petition from a Black person in Connecticut calling for the end of slavery. At the time the petition was printed, Connecticut had the largest Black population in New England. It’s possible Lambee was inspired by similar petitions in Massachusetts, and took ideas from them to incorporate into their own appeal. What stands out about this petition, however, is that it was addressed to the Sons of Liberty, a Patriot group that was increasing with popularity. As the petition states, Lambee found more hope in petitioning Patriots than the actual government.1

To the Sons of Liberty in Connecticut.

The humble Petition of a Number of poor Africans

Gentlemen,

Your characters, as Sons of Liberty, oblige us to think you the most zealous assertors of the natural rights and liberties of mankind in general; where-in we shall make bold a little to press you with our unhappy circumstances as slaves, begging your kind exertions on the behalf of your petitioners, for their deliverance from a state of unnatural servitude and bondage.

Your petitioners apprehend that liberty, being founded on the law of nature; is as necessary to the happiness of an African as to the happiness of an Englishman; and as much to be desired by the former as it can possibly be by the latter; and that we, not-withstanding our present state of slavery, have, in common with other men, a natural right to be free, and without molestation to enjoy such property as we by our honest industry may acquire; and that no person can have any just claim to our services, unless we have by the laws of the land forfeited them, or by voluntary compact made ourselves servants; neither of which is our case– But we were by the cruel hand of power, some of us dragg’d from our native country, and forced to forsake the dearest connections in life; whilst others in infancy have been stolen from the bosom of their tender parents, and brought to this distant land to be enslaved, and to serve like a horse in a mill. –Thus are we deprived of everything that tends to render life even tolerable, much less desirable.

The endearing ties of husband, wife, parent, child and friend, we are generally strangers to in our state of slavery, being entirely at the controul of our masters respecting the formation of such connections, and when any of those connections are formed among us, how are the pleasures embittered by the cruel consideration of our slavery, and the thoughts of our being separated at the will of our masters! — Thus are we by our deplorable situation in life, rendered incapable of shewing our obedience to the supreme Governor of the Universe… for how can a slave who is under the absolute controul of his master, perform the duties of husband, wife, parent or child?… So contrary is slavery to the genius of Christianity, that we are by our situation often hindred from the observance of the laws of God, and consequently deprived of an equal benefit in the laws of the land with other subjects; — as we are informed there is no law of this colony whereby our masters can hold us in slavery, unless mere custom (however ill founded) be deemed a law, and that the charter of this colony puts us on a level with other men, respecting freedom and all its attendant blessings. Custom therefore must be the only tyrant that keeps us in bondage, while the charter and the super-added laws of the colony are blameless. –We are not insensible, that if we should be liberated, and allowed by law to recover pay for our past services, our masters interests would be greatly damnified: but we claim no rigid justice– we ask no more in compensation for our past toils and sufferings, than only to be released from our present confinement, and allowed the free use of our natural rights and privileges.

There have been sundry petitions of this tenor to the legislative body of this colony for our relief; but as those in authority generally consist of such men as are interested in slavery; and though we mean not to reflect, as interest sometimes blinds the best of men, yet we have very little reason to expect any relief from that quarter, unless the common people, fraught with the manly feelings of the foul, should undertake, and use their influence in our behalf.

We would therefore humbly pray, that whilst you are consulting, asserting, and maintaining your own natural rights against the arbitrary designs of those who would subject you to slavery, that you would think on our unhappy case, who have been long groaning under the insupportable burden. –We are poor ignorant creatures, by reason of our circumstances as slaves, and know not what method to devise, being shut out from the use of law and the benefit of petitioning in a legal way; being by unnatural custom called the property of others, although a part of the same species of beings which alone can be called proprietors on earth; by which the order of nature is inverted — Proprietor and property confounded.

Our case being thus, we would earnestly intreat of you to hear our cries, and exert yourselves in our behalf, and consult such measures as you shall judge most feasible, in order to facilitate our deliverance, and so receive the grateful acknowledgments of thousands now unhappy. And your petitioners in duty bound, shall ever pray.

Signed Bristo Lambee

At the desire and in behalf of many others.

Black Americans and the American Revolution

By the time of the American Revolution, there was a sizable Black population in the colonies. Black Americans were involved in several ways, and witnessing the revolution around them was just one such way.

As witnesses to a unique time in history, Black Americans offered their own opinions and observations of the events around them. For some, this proved crucial in finding and fighting for freedom. For others, this meant they could contribute their own opinions to the chorus of revolutionary-era rhetoric.

Sources

- Isabelle Laskaris, “‘Thousands Now Unhappy’: Slave Petitions in Eighteenth-Century Connecticut,” Slavery & Abolition 44, No. 1 (2023): 26–47.