Liberty Further Extended: Or Free thoughts on the illegality of Slave-keeping

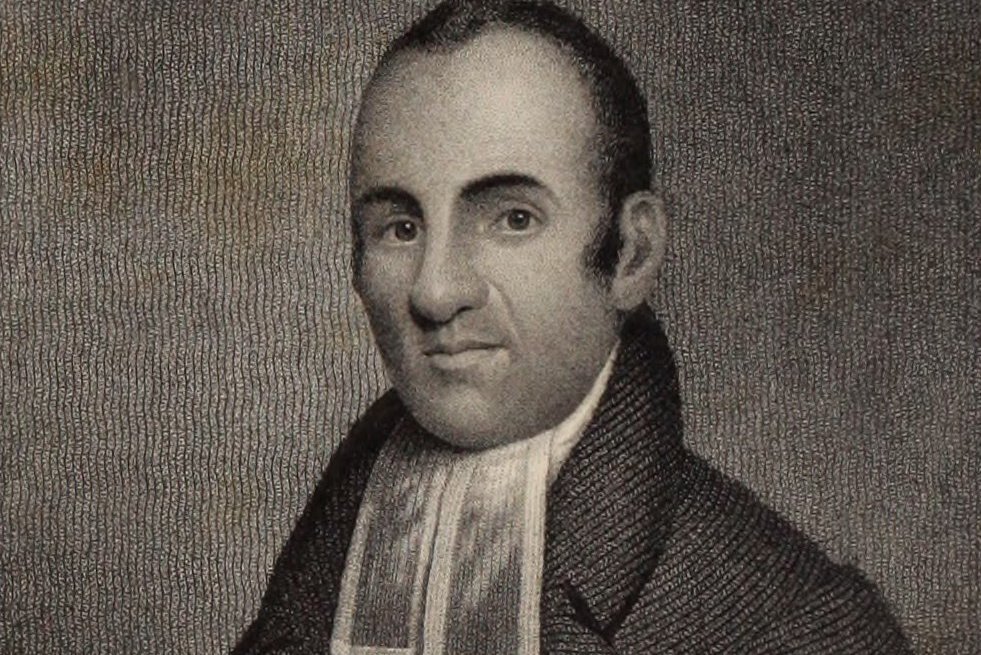

Lemuel Haynes was an African-American minister in New England. Born on July 18, 1753, his life illustrated how Black Americans, particularly in the north, could navigate hardening racial boundaries for a time.1

Haynes was the illegitimate child of a Black father and white woman, who supposedly belonged to a “respectable” family in West Hartford, Connecticut. Abandoned by his mother at only five months, Haynes was put into the care of David Rose, whose family lived in Middle Granville, Massachusetts. As was the law in many places for illegitimate children such as Haynes, he was indentured to Rose until he was 21 years old. Rose was a Congregational deacon and Haynes received an education at home and at a district school, as he was trained to become a member of the clergy.2

After completing his indenture, Haynes joined the local minutemen, and later briefly served in the Revolutionary War, before contracting typhus and being discharged in November 1776. By 1780, Haynes had completed a haphazard education among local ministers, and became a licensed preacher. He began work as a fill-in pastor at a local church. In 1783, with the approval of fellow ministers, he married Elizabeth Babbitt, a white schoolteacher. Two years later, he became fully ordained. He would serve in various posts throughout Connecticut, before being dismissed in 1818 because of his well-known pro-Federalist views. However, his dismissal was also likely influenced by increasingly rigid views on race among white northerners.3

Haynes continued to minister to various congregations across in Vermont and New York until his death on September 28, 1833. Haynes achieved a level of notoriety during his life, especially before his dismissal in 1818.4

Haynes’s life was somewhat out of the ordinary. He was a mixed-race Black child raised in a white family, who grew up to be a Black preacher to mostly white congregants. He was also one half of an interracial marriage. Yet his preaching was not one which leveraged his position to advocate for others like himself. In fact, on the issue of slavery, Haynes was unusually silent, having only mentioned it a handful of times in his published works.5

However, an unpublished and unfinished draft pamphlet from 1776 broke sharply with his overall public image. In a blistering attack on slavery and the slave trade, Haynes explored religious justifications for slavery, the nature of freedom, and comes very close to outright advocating for violent resistance among enslaved people. Repeatedly, Haynes placed his arguments within the ongoing imperial crisis, using the American Revolution to bolster his arguments.

The pamphlet ends mid-sentence, and it is unknown if it was ever finished, or in fact if Haynes ever had any intentions of finishing it. Crossed out words, sentences, and rewrites indicate Haynes was putting a lot of thought and effort into the manuscript. It’s clear, given the format, that Haynes wrote it with the intention to seek publication. But that never came. Whether Haynes ultimately changed his mind about publishing the pamphlet, or was simply unable to, will likely remain a mystery. But the draft manuscript is an important source for early Black Americans’ views on slavery and race, particularly during the American Revolution.

(Excerpts printed below. Bracketed words have been inserted in cases where Haynes’ spelling makes a word difficult to understand.)

…

Liberty, & freedom, is an innate principle, which is unmovably placed in the human Species; and to see a man aspire after it, is not Enigmatical, seeing he acts no ways incompatible with his own Nature; consequently, he that would [infringe] upon a mans Liberty may reasonably Expect to meet with opposition, seeing the Defendant cannot Comply to Non-resistance, unless he Counter-acts the very Laws of nature.

Liberty is a Jewel which was handed Down to man from the cabinet of heaven, and is Coaeval with his Existance. And as it proceed from the Supreme Legislature of the univers, so it is he which hath a sole right to take away; therefore, he that would take away a mans Liberty assumes a prerogative that Belongs to another, and acts out of his own domain.

One man may bost a superorety above another in point of Natural previledg; yet if he can produse no [convincing] arguments in vindication of this [preeminence] his hypothesis is to Be Suspected. To affirm, that an Englishman has a right to his Liberty, is a truth which has Been so clearly Evinced, Especially of Late, that to spend time in illustrating this, would be But Superfluous tautology. But I query, whether Liberty is so contracted a principle as to be Confin’d to any nation under Heaven; nay, I think it not hyperbolical to affirm, that Even an affrican, has Equally as good a right to his Liberty in common with Englishmen.

I know that those that are concerned in the Slave-trade, Do pretend to Bring argumetns in vindication of their practices; yet if we give them a candid Examination, we shall find them (Even those of the most cogent kind) to be Essencially Deficient. We live in a day wherein Liberty & freedom is the subject of many millions Concern; and the important Struggle hath alread caused great Effusion of Blood; men seem to manifest the most sanguine resolution not to Let their natural rights go without their Lives go with them; a resolution, one would think Every one that has the Least Love to his country, or [future] posterity, would fully confide in, yet while we are so zelous to maintain, and foster our own invaded rights, it cannot be tho’t impertinent for us Cadidly to reflect on our own conduct, and I doubt not But that we shall find that subsisting in the midst of us, that may with propriety be stiled Opression, nay, much greater opression, than that which Englishmen seem to much to spurn at. I mean an oppression which they, themselves, impose upon others.

…

And as some6 have manifested a Disposition to rise in their Defence, they have Been put to the most Cruel torters, and Deaths when in fact they had as good a right to rise in Defence of their own Natural rights and Libertyes as a man would have to repel the assaults of a hyghway robber as human art could inflict. Nay, such as is scearsly known amongs savages: When in fact, they had as good a right to rise in the Defence of their own natural rights and Libertys, as a man would have to repel the assaults of a hyghway robber.

…

O! what an [immense] Deal of Affrican-Blood hath Been Shed by the inhuman Cruelty of Englishmen! that reside in a Christian Land! Both at home, and in their own Country? they being the fomenters of those wars, that is absolutely necessary, in order to carry on this cursed trade; and in their Emigration into these colonys? and By their merciless masters, in some parts at Least? O ye that have made yourselves Drunk with human Blood!... What will you Do in that Day when God shall make inquisision for Blood? he will make you Drink the phials of his indignation which Like a potable Stream shall Be poured out without the Least mixture of mercy…

…

But altho god is of Long patience, yet it does not Last always, nay, he has whet his glittering Sword, and his hand hath already taken hold on Judgement; for who knows how far that the unjust Oppression which hath abounded in this Land, may be the procuring cause of this very Judgement that now impends, which so much portends Slavery?

for this is often God’s way of working, often Often he brings the Same Judgements, or Evils upon men, as they unriteously Bring upon others.

…

Therefore is it not hygh tiem to undo these heavy Burdens, and Let the Oppressed go free? And while you manifest such a noble and magnanimous Spirit, not to maintain inviobly your own Natural rights, and militate so much against Despotism, as it hath respect unto yourselves, you do not assume the same usurpations, and are no Less tyrannic. Pray let there be a congruity amidst you Conduct, Least you fall amongst that Class the inspir’d pen-man Speaks of.

…

Sirs, the important Caus in which you are Engag’d in is of a very Exelent nature, ‘tis ornamental to your Characters, and will, undoubtedly, immortalize your names thro’ the Latest posterity. And is is pleasing to Behold that patriottick Zeal which fire’s your Breast; But it is Strange that you Should want the Least Stimulation to further Expressions of so noble a Spirit. Some gentlemen have Determined to Contend in a Consistant manner; they have Let the oppressed go free; and I cannot think it is for the want of such a generous princaple in you, But thro’ some inadvertency that

*End of manuscript

Black Americans and the American Revolution

By the time of the American Revolution, there was a sizable Black population in the colonies. Black Americans were involved in several ways, and witnessing the revolution around them was just one such way.

As witnesses to a unique time in history, Black Americans offered their own opinions and observations of the events around them. For some, this proved crucial in finding and fighting for freedom. For others, this meant they could contribute their own opinions to the chorus of revolutionary-era rhetoric.

Sources

- Ruth Bogin, “‘Liberty Further Extended’: A 1776 Antislavery Manuscript by Lemuel Haynes,” William and Mary Quarterly 40, No. 1 (January 1783), 85.

- Bogin, “‘Liberty Further Extended,’” 85–86.

- Bogin, “‘Liberty Further Extended,’” 86–87.

- Bogin, “‘Liberty Further Extended,’” 87.

- Bogin, “‘Liberty Further Extended,’” 88–89.

- Here Haynes is speaking about enslaved people being transported across the Atlantic on slave ships.