Jupiter Hammon (1711-c.1806)

Jupiter Hammon was born on October 17, 1711, at the Lloyd Manor in Long Island. It is suspected his parents were Opium and Rose, two enslaved people purchased by Henry Lloyd. Likely as a child, Hammon was allowed to receive a general education through the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts, a branch of the Anglican Church that worked to convert and educate enslaved people. His education allowed him to not only work as a clerk for the Lloyd family, but also become a published author.1

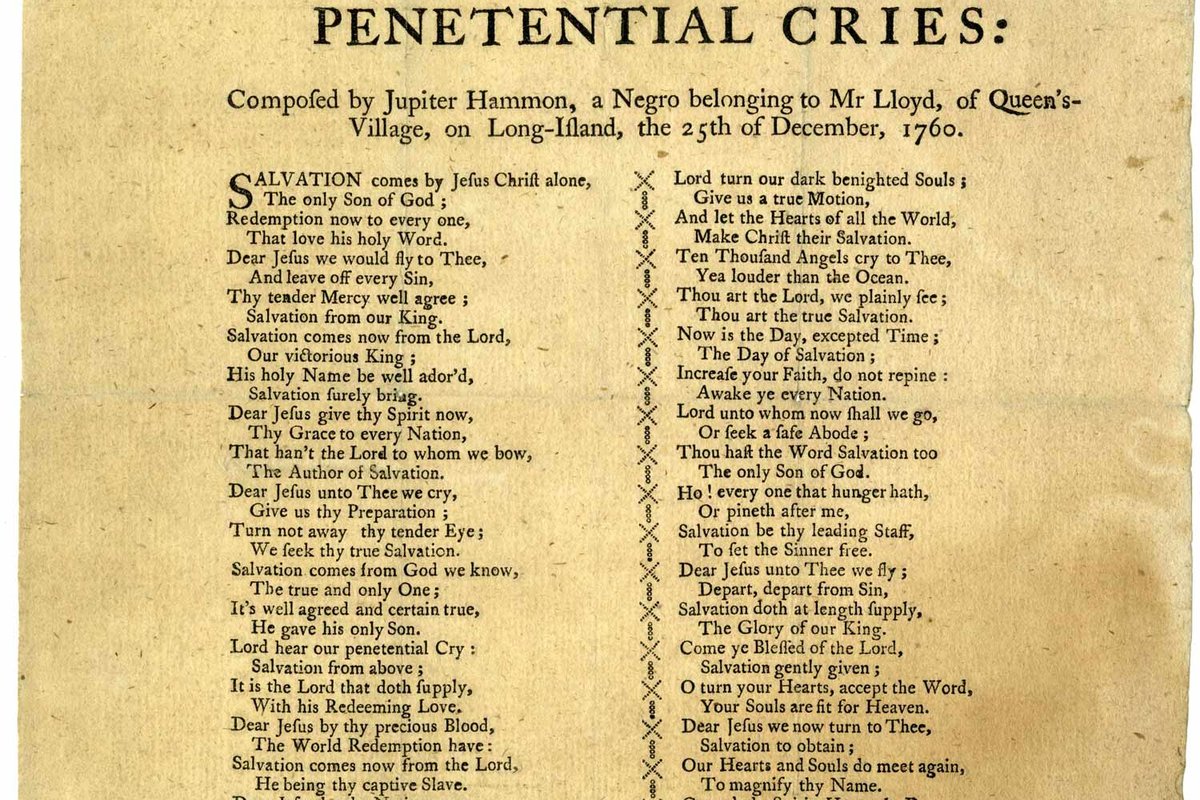

In 1761, Hammon became the first published African-American poet in the British Atlantic. Composed the year before, his piece, entitled An Evening Thought: Salvation by Christ, with Penitential Cries, would be indicative of his works, which largely explored the relationship between Christianity, the African American community, and slavery.2 It would be another eighteen years, however, before Hammon would have another poem published.

His second poem was addressed to Phillis Wheatley. Likely inspired by her 1773 Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, Hammon’s poem was a way of connecting and encouraging the younger poet.3

Hammon’s most famous publication was his speech to the African Society in New York City on September 24, 1786. The last of only eight total publications, it was nonetheless quite impactful. At 74 years old, and still enslaved, Hammon addressed those in attendance on how enslaved people would find freedom in Heaven, and be free of racism.4

Likely dying sometime around 1806, Hammon had been enslaved his entire life by four generations of the Lloyd family. His limited list of publications, nonetheless, contributed to early African American literature before, during, and after the American Revolution.

Black Americans and the American Revolution

By the time of the American Revolution, there was a sizable Black population in the colonies. Black Americans were involved in several ways, and witnessing the revolution around them was just one such way.

As witnesses to a unique time in history, Black Americans offered their own opinions and observations of the events around them. For some, this proved crucial in finding and fighting for freedom. For others, this meant they could contribute their own opinions to the chorus of revolutionary-era rhetoric.

Sources

- Faith Berry, ed., From Bondage to Liberation: Writing by and about Afro-Americans from 1700 to 1918 (The Continuum International Publish Group Inc., 2006), 50–51.

- Jupiter Hammon, An Evening Thought: Salvation by Christ, with Penetential Cries (1961).

- Rosemary Fithian Guruswamy, “‘Thou Has the Holy Word’: Jupiter Hammon’s ‘Regards’ to Phillis Wheatley,” in Genius in Bondage: Literature of the Early Black Atlantic, ed. Vincent Carretta and Philip Gould (University Press of Kentucky, 2001): 190–98.

- James G. Basker and Nicole Seary, eds., Black Writers of the Founding Era (Library of America, 2023), 307.

- Rosemary Fithian Guruswamy, “‘Thou Has the Holy Word’: Jupiter Hammon’s ‘Regards’ to Phillis Wheatley,” in Genius in Bondage: Literature of the Early Black Atlantic, Vincent Carretta and Philip Gould, eds. (University Press of Kentucky, 2001): 190–98.

- Phillip M. Richards, “Nationalist Themes in the Preaching of Jupiter Hammon,” Early American Literature 25, No. 2 (1990), 131–32.

- Cedrick May and Julie McCown, “‘An Essay on Slavery’: An Unpublished Poem by Jupiter Hammon,” Early American Literature 48, No. 2 (2013): 457–71.