A Sermon, on the Present Situation of the Affairs of America and Great-Britain by a Black Whig

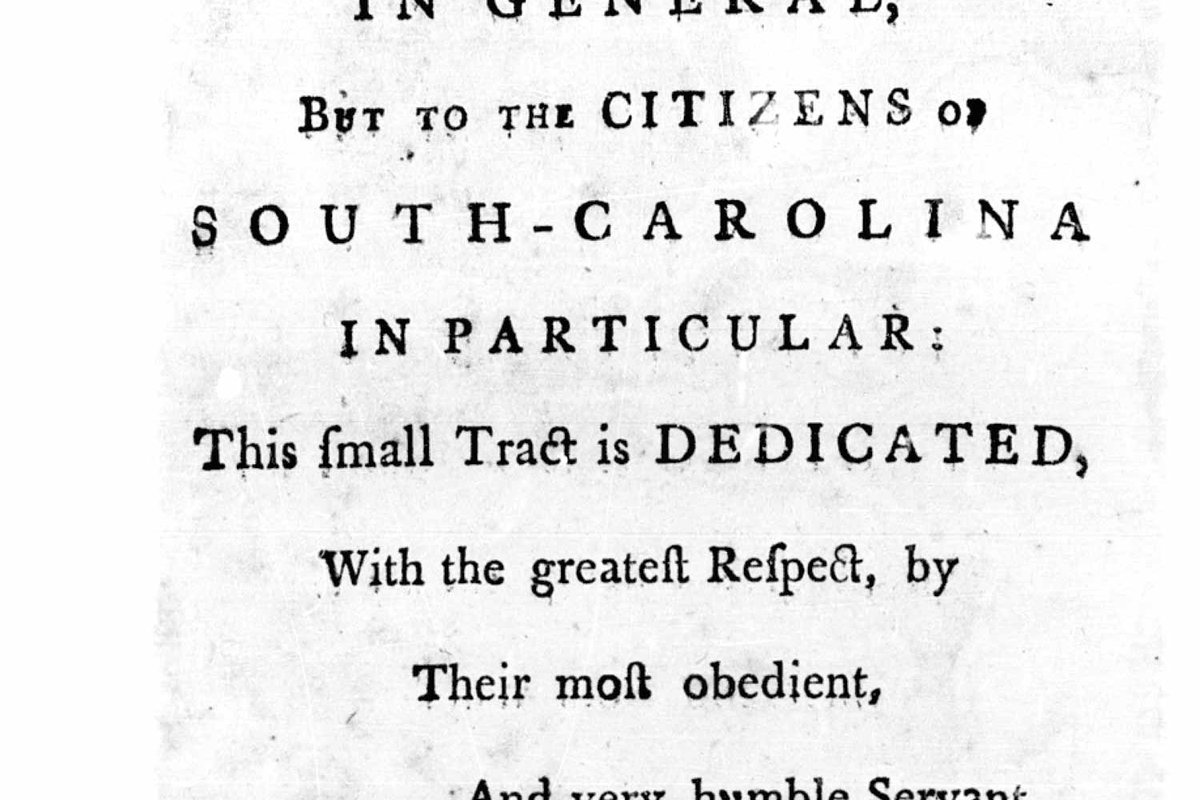

Between 1781 and 1783, three short pamphlets were printed and distributed in Philadelphia. While each pamphlet is signed with a different pseudonym, given the thematic and linguistic similarities, along with the fact that each is addressed to the people of South Carolina, it is likely they all had the same author.1

Signed “A Black Whig,” “an African American,” and “An Aethiopian,” it is impossible to know whether or not the author was actually Black. Regardless, readers would have likely taken the writer at their word that they were, in fact, Black. This means that readers of the pamphlets would have believed they were reading ideas about the nation, slavery, abolition, and religion from a Black person.

The below sermon was the first to be published, and signed by “A Black Whig.” It extols American independence as a divinely righteous cause. At the time, the people of South Carolina, whom the sermon was addressed to, lived under British occupation. In the piece, the author offers hope that America will prove triumphant, ties abolition of slavery to American freedom, and also singles out the women of South Carolina as commendable.2

Below are excerpts from the sermon.

THE AUTHOR'S PREFACE.

THE reason why the author's name is concealed, will, I hope, do no injustice to this short piece. He has taken the liberty of a citizen, though unacquainted with learned phrases and grammatical questions, to offer this to every son of freedom; and as it was not intended for the public eye, hopes the critic will forgive all errors. He only adds, that, if any sentences contained therein, should kindle the smallest emotion of joy in an American breast, he will think his labour amply rewarded.

…

But America has no such views, she wants no titles nor kings; she is struggling for nothing but liberty, peach and independence, and the quiet possession of that country which their ancestors helped to win from the hands of barbarous savages…

…

America! a name which I hope will be remembered while the sun and moon endure: An empire which, in my opinion, in spight of all opposition, will be one of the greatest in the world! O infatuated Britain! if thou hadst known in this thy day the things that belonged to thy peace, though wouldst never had pretended to enslave America! O unhappy was that morn, when the word was given to charge a bayonet! on a brother American! O unnatural, unchristian war!

…

Nothing but superiority has given them any victories that they have ever gained; not their valour–And these victories have been oftentimes so dearly bought, that they have been almost equal in their consequences to a total defeat.–They have armed domestics to fight against their masters, contrary to the laws of civilized nations.–They have hired foreign mercenaries to accomplish their base designs; but their most vigorous efforts have proved abortive.

…

However inveterate Great-Britain may be against the independencey of America, it shall be established and built on that ruins of British tyranny; and blessed be the grand Arbiter of nature, that we are supported by our good ally Louis the Sixteenth, the supporter of the rights of mankind–And now my virtuous fellow citizens, let me intreat you, thata, after you have rid yourselves of the British yoke, that you will also emancipate those who have been all their life time subject to bondage.

…

Pardon me, I cannot conclude before I address myself to the virtuous daughters of Carolina, whose courage, perseverance and fortitude are equal to the daughters of ancient Rome and Sparta. After being deprived of the companions of their lives, and insulted by the enemies of America, they still maintained their ground, and have followed their exiled partners across the mighty deep.–O ye virtuous daughters, many daughters have done well, but ye excel them all.

…

Black Americans and the American Revolution

By the time of the American Revolution, there was a sizable Black population in the colonies. Black Americans were involved in several ways, and witnessing the revolution around them was just one such way.

As witnesses to a unique time in history, Black Americans offered their own opinions and observations of the events around them. For some, this proved crucial in finding and fighting for freedom. For others, this meant they could contribute their own opinions to the chorus of revolutionary-era rhetoric.

Sources

- James G. Basker and Nicole Seary, eds., Black Writers of the Founding Era, 1761-1800 (Library of America, 2023), 207, 221, 233.

- Basker and Seary, Black Writers of the Founding Era, 207.