Black Americans and the American Revolution

On This page

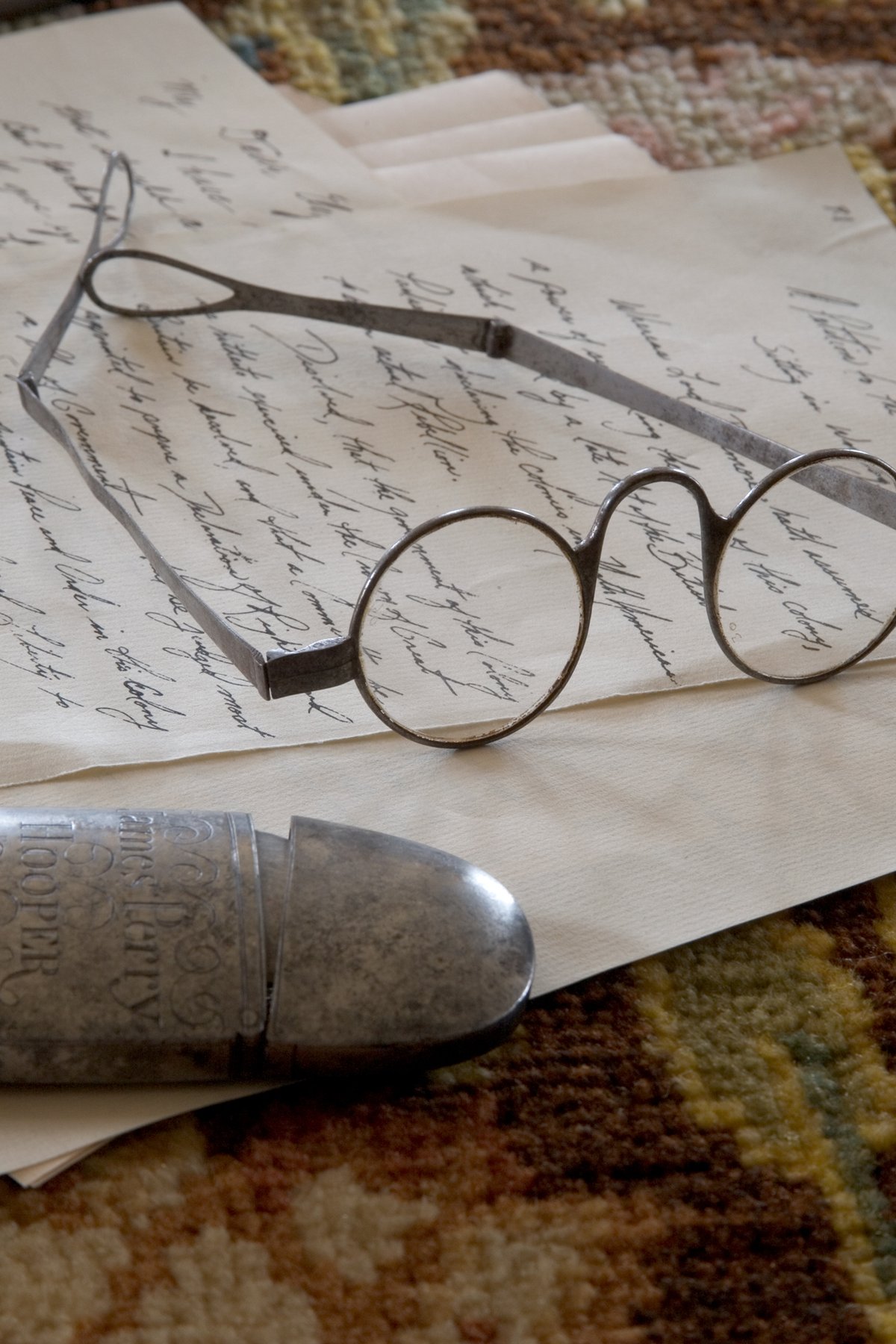

Witnessing a Revolution

The American Revolution is often portrayed as a moment, in the words of John Adams, in which the “Minds and Hearts of the People” underwent a shift, as colonists reexamined their place within the British Empire.1 Yet when Adams spoke, he was only referring to white colonists and soon-to-be American citizens. By the time of the American Revolution, there was a sizable Black population in the colonies. The vast majority of these people were enslaved, but some lived their lives as freemen. The American Revolution may not have been for their sake, but Black Americans were nonetheless involved in several ways. Witnessing the revolution around them was just one such way.

Witnessing, however, was not a passive action. Instead, as witnesses to a unique time in history, Black Americans offered their own opinions and observations of the events around them. For some, this proved crucial in finding and fighting for freedom. For others, this simply meant they could contribute their own opinions to the chorus of revolutionary-era rhetoric. In any case, Black Americans were active participants in the revolution around them.

Fighting a War

As the American Revolution turned into an armed conflict, many Black Americans, whether free or enslaved, had to choose which side they thought best served their interests. Freedom, a better life, upward mobility, and much more were goals that influenced how Black Americans made their choices. Some chose to fight for the American cause, or were forced to by their enslavers. Many others chose to side with the British, believing there would be a commitment to creating a more equitable society following the war’s end.2

Many Black people would not have been able to leave behind sources about their time during the war. There are few sources that survive from this event. What few remain, however, shed some light on their experiences, and the lives they may have lived following their time fighting in the War for Independence. Black people have a variety of reasons for choosing to take one side over the other. They made claims on both America and Britain, using their faithful service as a means to bolster their demands. In short, Black people were not passive onlookers to the Revolutionary War, but key members of that armed conflict, who sometimes used it as a way to forge a better life.

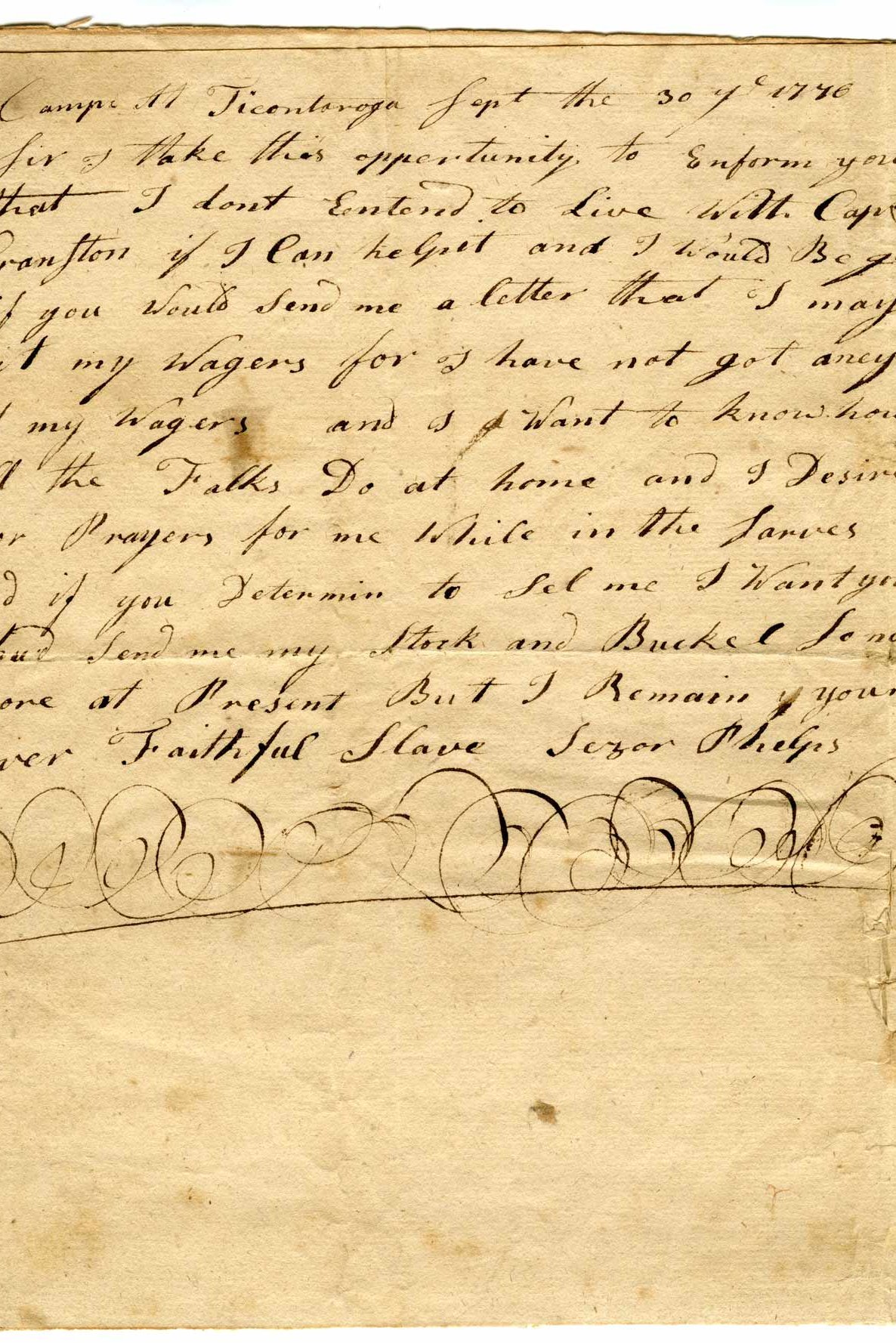

Sezor Phelps's Letter

Writing from Fort Ticonderoga, Sezor Phelps sent a letter to his enslaver, Charles Phelps Jr. The short letter touches on Sezor's service in the Continental Army and his enslavement.

Murphy Stiel's Warning

Murphy Stiel was a member of the Black Pioneers, a company of Black loyalists in the British Army. Somone recorded his prophetic warning to George Washington about enslaved people rising up for freedom.

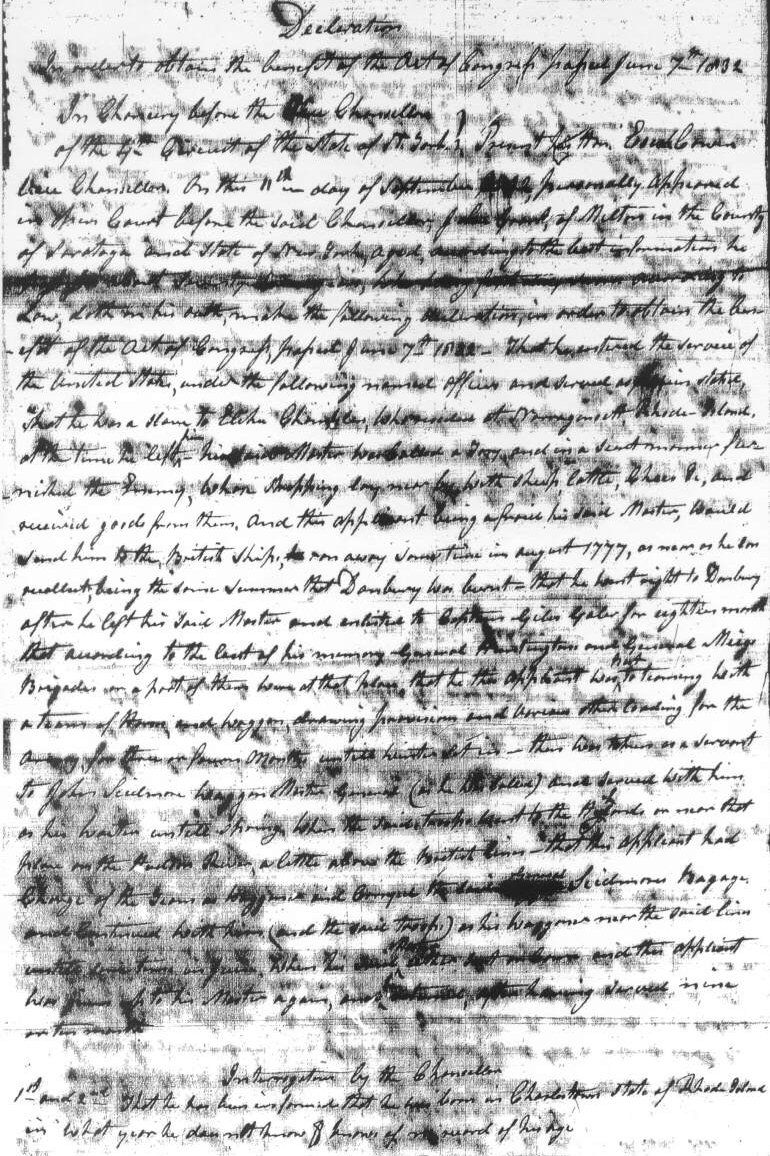

Denying Jehu Grant

At the age of 80, Jehu Grant was one of the few surviving Black veterans of the Revolutionary War to become eligible for a pension in the 1830s. His attempt to claim one, however, was denied.

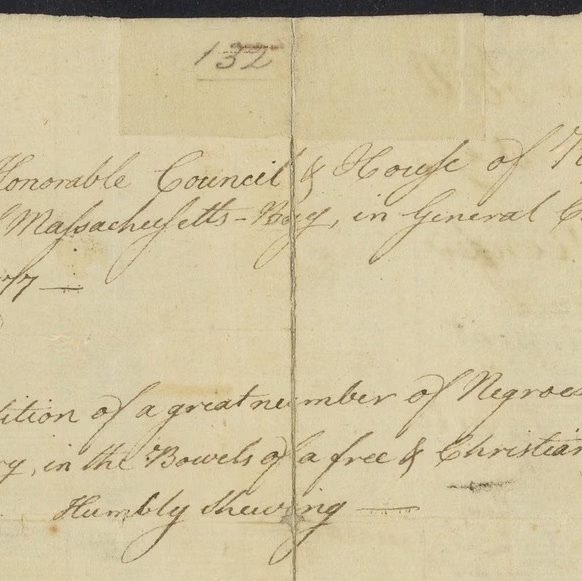

Petitioning for Liberty

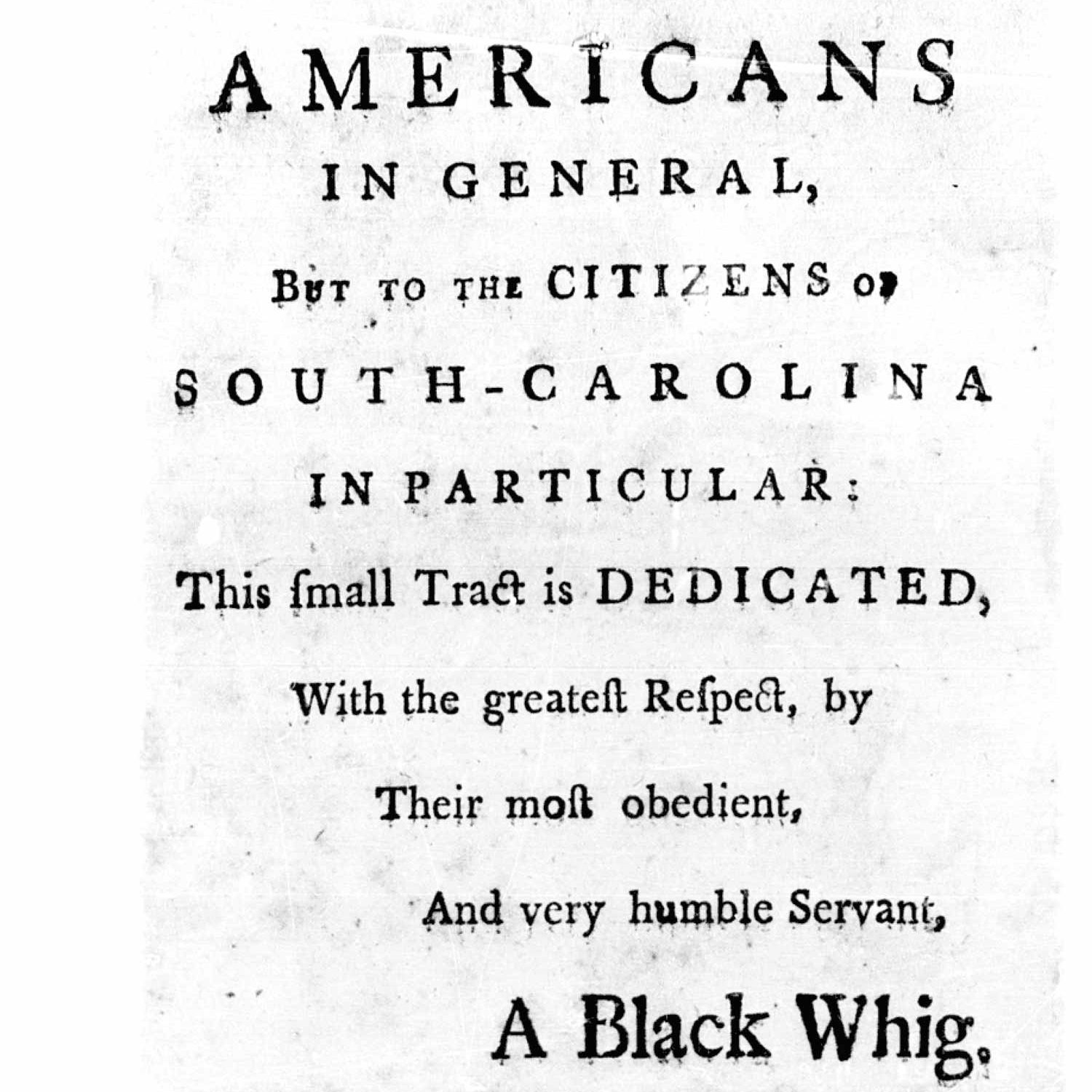

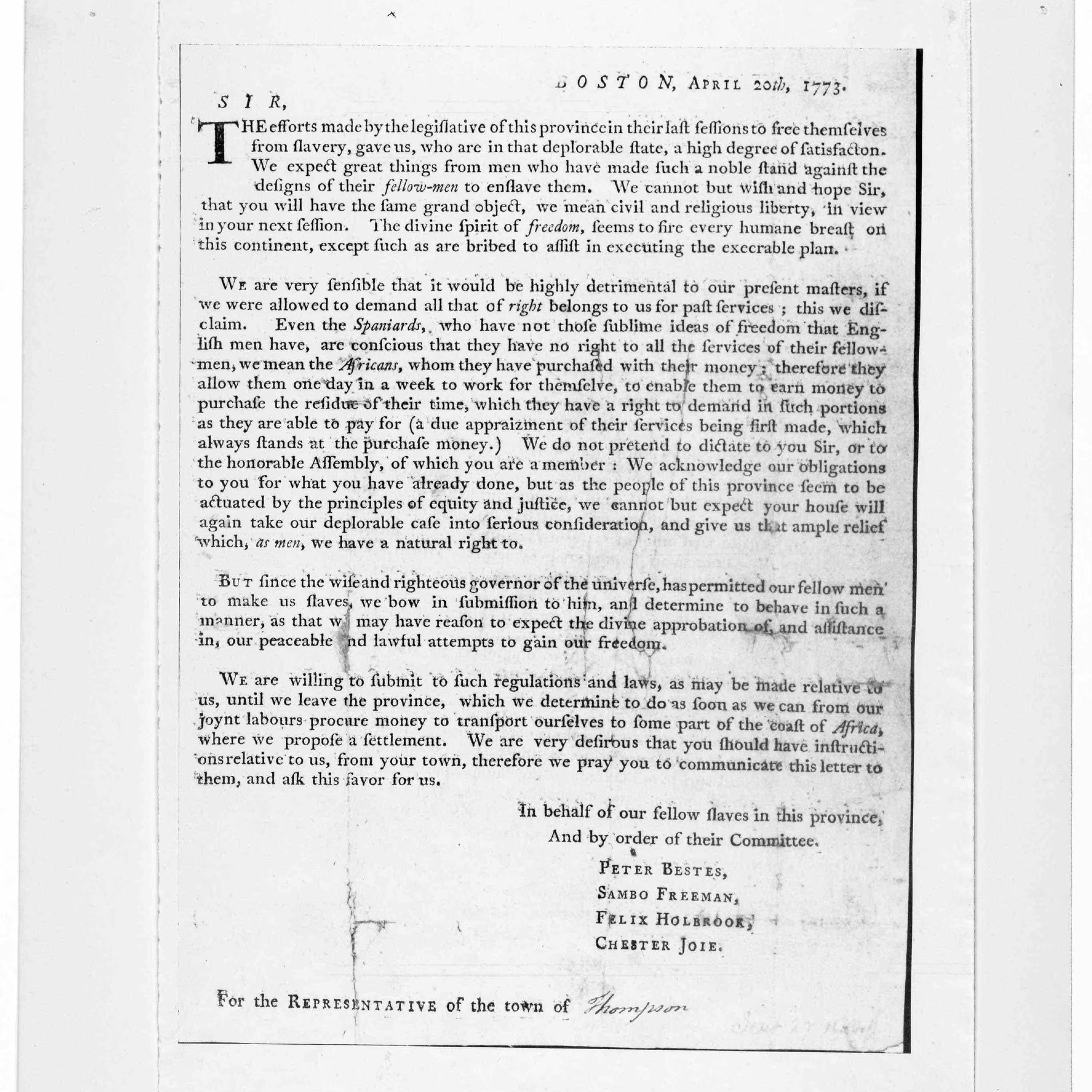

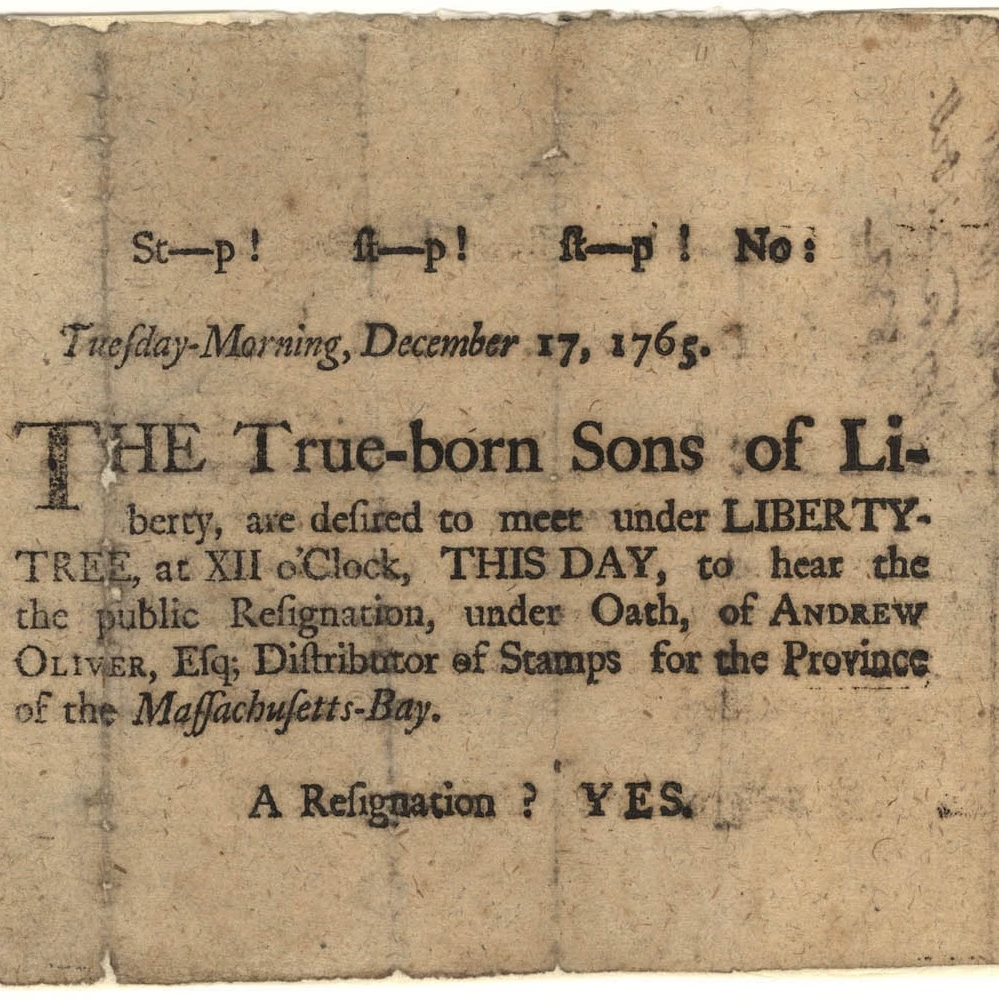

Throughout the 1770s, New England colonies saw a number of different petitions from both free and enslaved Black colonists, seeking an end to both the international slave trade and slavery itself. Petitioners and their allies adopted the revolutionary language used by Patriots to defend their own rights against Parliament. Doing so not only tied their appeals to the ongoing struggle for liberty, but also drew attention to the shortcomings and hypocrisies of the ongoing Revolution. These petitions represent a mix of wholehearted attachment to the American cause, calculated employment of revolutionary language, and new ideas about what liberty could represent.3

Poetic Genius

The artistic abilities of Black Americans challenged preconceived notions surrounding both race and slavery in the colonies and the new nation. Black people were generally believed to be inferior to their white counterparts, especially intellectually. Such thinking was just one of many reasons used to justify both slavery and the liminal status free Black people held in society. When given the opportunity to gain an education and express themselves, however, Black people were able to push back against such ideas.4

Phillis Wheatley Peters and Jupiter Hammon were contemporaries of each other in New England. Both were enslaved, though Wheatley Peters would eventually gain her freedom. Wheatley Peters became a well-known poet at a young age, becoming the first Black person in America to have a book of poetry published. Hammon was not only a poet but also a preacher and clerk, and was the first Black person to have a piece of literature published in North America. Both Wheatley Peters and Hammon advocated for themselves and others in their own ways, pushing back against the systems of oppression in subtle but important ways.

A Child of Poetry

Phillis Wheatley Peters was forcibly brought to America as a young child. She soon proved to be a prodigy, quickly learning and publishing a book of poetry just 12 years after being sold into slavery.

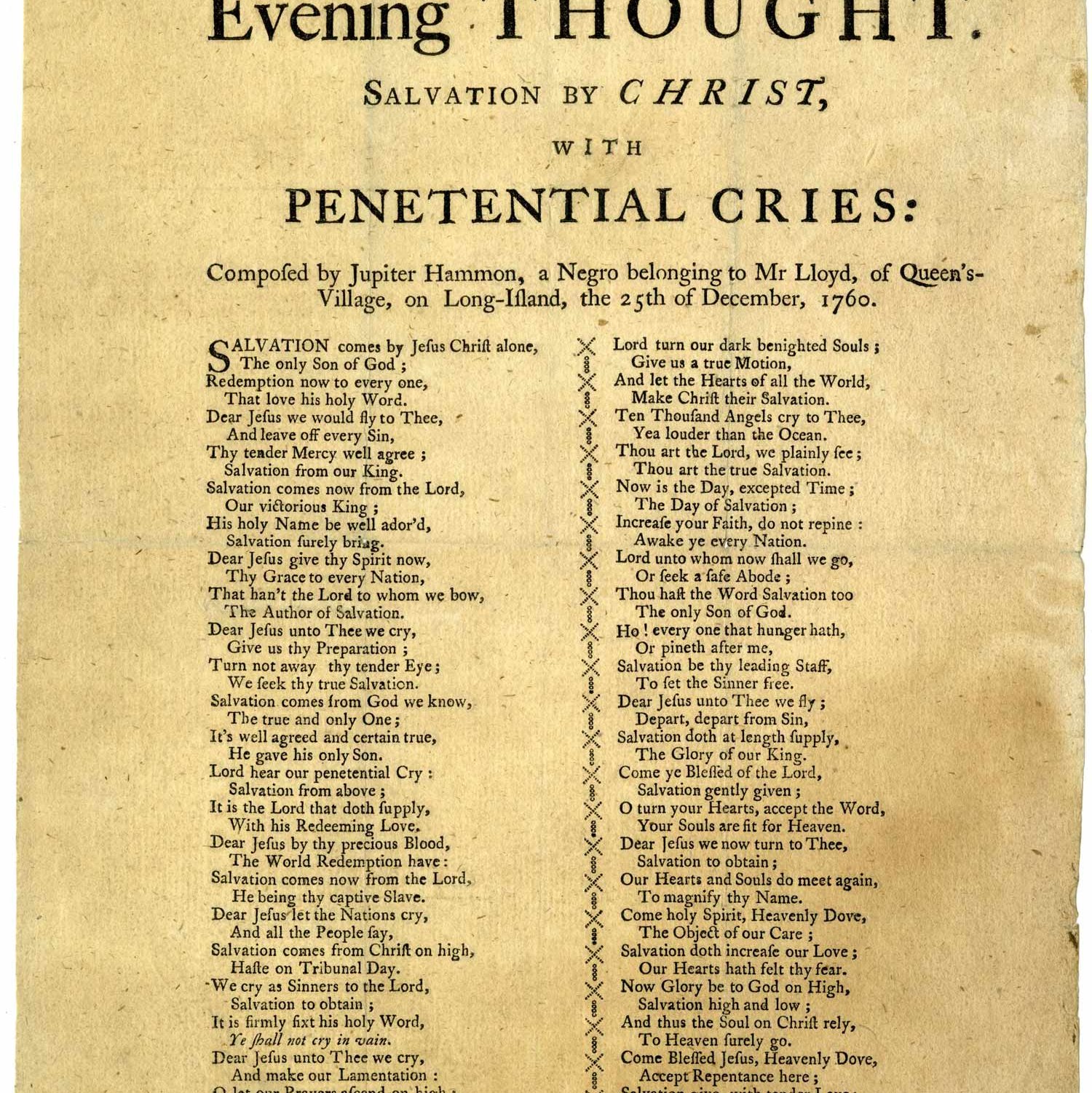

Paving the Way

Jupiter Hammon was the first Black American to publish a piece of literature. He wrote poetry and prose. Publishing only a handful of works, he nonetheless paved the way for Black American literature.

Resources

Explore More

Stories of Black Life

By the late 18th century, half of Williamsburg’s population was Black. Discover these American stories of resilience and explore those who lived, loved, and strove to create a better future.

Sources

All research begins with a question and that carefully crafted question guides the work. Those questions are answered and supported by using primary and secondary sources.

Road to Independence

How did Virginia move so quickly from royalism to independence? Go deeper to learn more about how the people of Williamsburg led the way toward the American Revolution.

Sources

- John Adams to Hezekiah Niles, February 13, 1818, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/99-02-02-6854.

- Alan Gilbert, Black Patriots and Loyalists: Fighting for Emancipation in the War for Independence (The University of Chicago Press, 2012).

- Joanna Brooks, “The Early American Public Sphere and the Emergence of a Black Print Counterpublic,” William and Mary Quarterly 62, no. 1 (2005): 74; Manisha Sinha, “To ‘Cast Just Obliquy’ on Oppressors: Black Radicalism in the Age of Revolution,” William and Mary Quarterly 64, no. 1 (2007): 149-153; Grant Stanton, “The Freedom Petitions: Black Patriotism, Black Politics, and the Abolition of Slavery in Massachusetts, 1773-1783,” Early American Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal 22, No. 2 (Spring 2024), 262-304.

- Nicholas Guyatt, Bind Us Apart: How Enlightenment Americans Invented Racial Segregation (Basic Books, 2016).