Dunmore's Proclamation and the Fight for Freedom

Fear and hope melded in uneasy tension throughout Virginia. Word of a proclamation that could change the fate of many made its way throughout the colony in late November of 1775.

Whispered voices carried word that Governor John Murray, Fourth Earl of Dunmore was offering freedom to enslaved people who came to his banner. Patriots saw the move by Dunmore as a treasonous ploy to incite a slave rebellion. Enslaved people across the colony saw it as an opportunity to grasp freedom.

It did not matter which side of the emerging colonial conflict a Virginian found themselves on. Patriot or loyalist, free or enslaved, white or Black. All were affected by Dunmore’s Proclamation. As the colonies seemed to barrel towards war, the stakes of the conflict suddenly felt higher for all involved.

The Prelude

Tension mounted throughout the early months of 1775. In Virginia, things came to a head after Lord Dunmore ordered the gunpowder in the Williamsburg Magazine to be secretly taken away in the early morning hours. Colonists awoke on April 21st to find themselves completely defenseless, a feeling made worse by weeks of pent up anxiety over rumors of possible slave uprisings.

A standoff between angered colonists and Dunmore ensued for weeks. While Dunmore swore the gunpowder could be returned if needed, he also made clear he wouldn’t suffer threats. He even promised to free enslaved people to fight by his side if any harm came to a single British official.

Fearing for their safety, Dunmore sent his family away and began fortifying the Governor’s Palace. Several weeks later, on June 8th, he fled Williamsburg, and would never return.

A “Piratical War”

Over the next months, Dunmore took refuge on British ships, and used them to raid coastal plantations. He used these raids to scare colonists, collect supplies, and bring enslaved people into his forces. While not all enslaved people believed it, many decided that his claims of emancipation were worth the risk.1

But the damage the raids did was more psychological than material. Dunmore’s forces were far too weak to effectively hold any territory. And Virginia patriots were so steadfast in their pursuit of Dunmore that he could scarcely step foot on land before being chased off. Dunmore continued his coastal raids, to varying degrees of success, in what acting-Governor Edmund Pendleton described as a “Piratical War.”2

The Proclamation

Months of patriot-described piracy did little to bring Virginia back under Dunmore’s control. There simply weren’t enough British forces in Virginia. Dunmore needed something to change the tide.

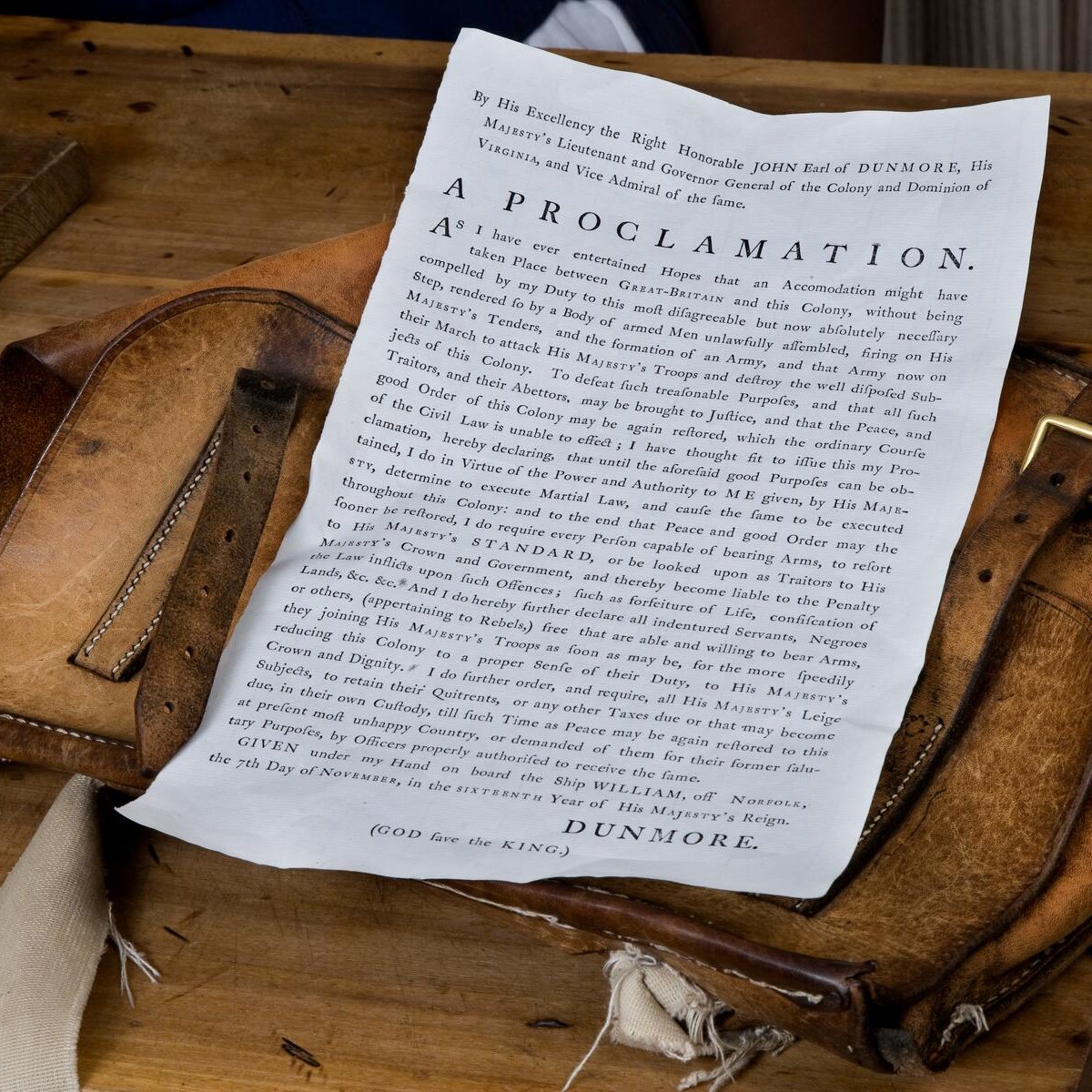

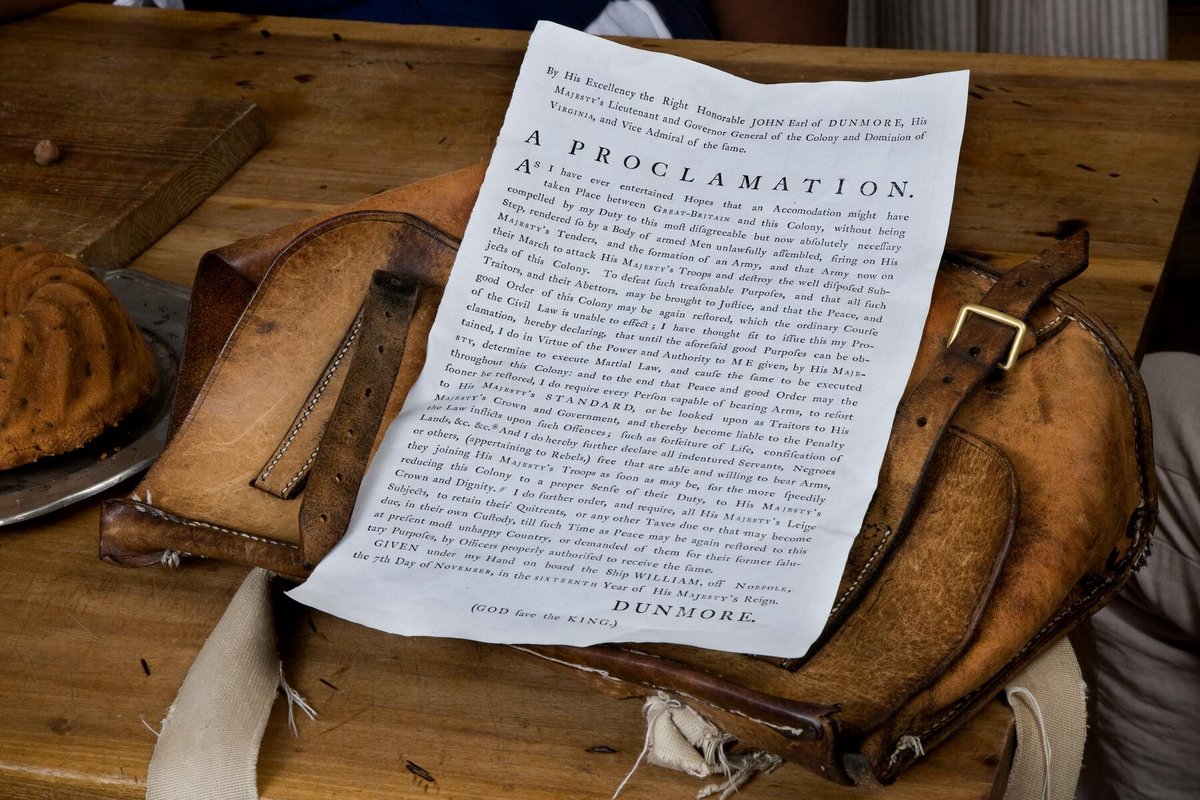

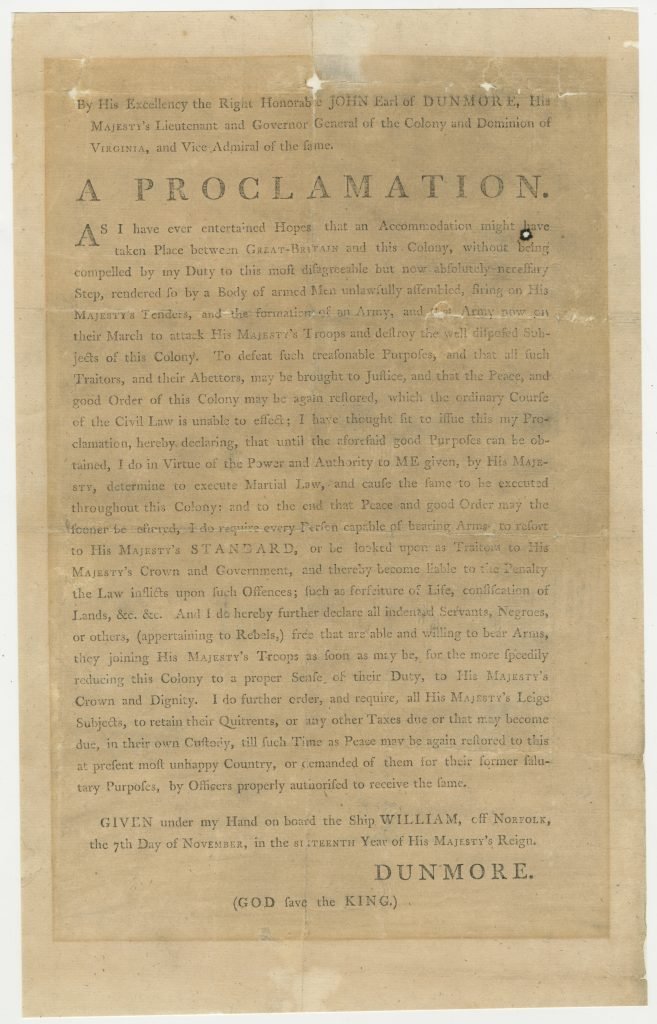

By November, Dunmore was ready to fully embrace the radical plan he had first threatened colonists with months earlier. On November 7th, he signed a proclamation that would change the course of the American Revolution not just in Virginia, but in all of British North America.

Dunmore’s Proclamation did three things. First, Dunmore declared martial law in Virginia, which technically gave him sweeping powers over the colony. Next, he required all those able to bear arms to fight under his banner. Those who refused would be “looked upon as Traitors,” and face all the consequences that entailed. Finally, and most importantly, Dunmore offered freedom to all “indented Servants, Negroes, or others (appertaining to Rebels)” who would fight for him.3

The next week after he defeated a small patriot militia at Kemp’s Landing in Princess Anne County, Dunmore read his proclamation.4 It sent shockwaves through Virginia and into the rest of the colonies.

While Dunmore’s Proclamation was potentially emancipatory for some enslaved people, it was nonetheless still a military measure meant, first and foremost, to help Dunmore take back control of Virginia. Ever since the Gunpowder Incident, enslaved people had been coming to Dunmore and offering their service in an attempt to find freedom. The steady wave of enslaved people seeking freedom through Dunmore pushed him towards making good on his earlier threats to enact some form of emancipation.5

By his Excellency the Right Honorable John Earl of Dunmore . . . A Proclamation (Broadside 1775). Special Collections, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia.

Dunmore used a printing press he had seized from John Holt to publish his proclamation. Holt’s Virginia Gazette: or, The Norfolk Intelligencer was vocally critical of Dunmore and other local British officials. In October, Dunmore seized Holt’s printing press, tools of trade, and anyone in the shop after Holt referenced the treasonous past of Dunmore’s father.6

Colonial Response

News of Dunmore’s Proclamation traveled quickly. Patriots across all thirteen colonies experienced an uneasy mix of anger, fear, and paranoia following Dunmore’s announcement. In Philadelphia, the Continental Congress accused Dunmore of destroying the very foundations of government in Virginia. In Maryland, desperate to keep control of their enslaved population, officials prohibited all correspondence from Virginia. One of South Carolina’s representatives to the Continental Congress, Edward Rutledge, claimed that the proclamation, more “than any other expedient, which could possibly have been thought of,” would cause the separation of the colonies from Britain. And in London, a letter from a Philadelphian told readers that “hell itself could not have vomited any thing more black than” Dunmore’s Proclamation.7

Virginians responded to Dunmore’s Proclamation by immediately increasing slave patrols to police Black people. Multiple instances of enslaved runaways being captured while fleeing to Dunmore appear in the Virginia Gazette. And the paper printed reports that their executions were meant as an example to others who contemplated the same action.8

An open letter printed in the Virginia Gazette aimed to convince enslaved Virginians that they shouldn’t trust Dunmore, and threatened them with harsh punishments if they were foolish enough to try their luck with the governor.9

The threat to Virginia’s racial order brought on by Dunmore’s Proclamation also pushed some white Virginians who were either neutral, or even loyal, to the patriot cause. Commenting on the proclamation, Richard Henry Lee noted with the exception of “a few Scotch excepted” Dunmore's actions had “united every Man” in Virginia.10

Fighting for Freedom

It’s unclear just how many enslaved people made it to Dunmore. Those who did almost certainly made up a relatively small fraction of the many who tried, but were caught before they could make it. Nonetheless, we know that hundreds of Virginia’s enslaved people were able to make their way to Dunmore in search for freedom. Others chose not to risk their, or their families’, lives. And others simply didn’t believe Dunmore. When asked what he thought of Dunmore’s Proclamation, Caesar, a well-known enslaved barber in the Yorktown area, was reported as saying “that he did not know any one foolish enough to believe him,” because if Dunmore was going to free anyone, “he ought first to set his own free.”11

While Dunmore’s Proclamation was aimed only at men capable of bearing arms, many enslaved people outside of that description flocked to his banner. It was not uncommon for family units to run away together. Over the remainder of 1775 into 1776, Dunmore’s flotilla of ships swelled with runaway enslaved people. Providing for all of these people proved incredibly difficult. Not only were supplies constantly low for Dunmore, but disease began running rampant, especially among enslaved people. Often forced into cramped and overcrowded quarters on ships, runaways suffered a variety of illnesses over the next months.12

Nonetheless, those capable of fighting were eager to prove their loyalty, and were organized into Dunmore’s Ethiopian Regiment. The unit was commanded by white officers, but was unique in that Black soldiers were actually armed and engaged in combat. As armed conflict shifted into war, the British army rarely used Black people in combat roles, with the exception of sailors. Instead, they performed manual labor. The Ethiopian Regiment, however, was trained and armed for battle.13

Virginia Gazette (Dixon & Hunter), December 2, 1775

Reports about Dunmore’s Ethiopian Regiment varied widely, and often vastly inflated its numbers. A common piece of information was that the unit’s soldiers had the phrase “Liberty to Slaves” on their clothing. However, no evidence supports these claims, and the Ethiopian Regiment did not even have uniforms. The claim is just one of many examples of the propaganda patriot presses engaged in to sway the minds of others, especially when it came to race and slavery.14

The Ethiopian Regiment, however, saw limited action. Dunmore’s military campaign was hindered by his lack of supplies, relatively small forces, and the persistent presence of disease. The most significant confrontation happened at the Battle of Great Bridge, outside Norfolk. In an attempt to secure Norfolk, Dunmore ordered his forces, including the Ethiopian Regiment, to attack amassing patriot forces on the opposite side of Great Bridge. Poor planning and leadership on the field led to a humiliating defeat that forced Dunmore to abandon Norfolk altogether.15

A Proclamation Left Behind

Going into 1776, Dunmore would pose a relatively small threat to Virginia, attempted to harass coastal plantations and welcomed enslaved people to his banner. But lack of supplies and troops were exacerbated when disease repeatedly hit his flotilla of ships, with the Black population hit especially hard. Eventually, Dunmore was forced to abandon Virginia altogether, sailing for New York, after patriots attacked a temporary camp set up to inoculate the flotilla’s Black population against smallpox. Only a few hundred loyalists and surviving Black civilians were able to evacuate with Dunmore, with almost as many sick and dying Black people left behind on the shores.16

Dunmore’s Proclamation was many things. For patriots, the Proclamation only reinforced the idea that Britain planned to subjugate the colonies by whatever means possible. When the Continental Congress was debating the draft language of Thomas Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence, they removed a section that criticized slavery. Instead, the Congress accused the king of exciting “domestic insurrections,” a reference to Dunmore’s Proclamation.17

Those relatively few remaining Black people nonetheless found freedom with Dunmore and the British. Dunmore may have lost Virginia, and his Proclamation may have been primarily a military expedient, but his actions represented a possible path out of slavery for many enslaved people in Virginia, even if most were unable to take advantage of it. Furthermore, Dunmore’s Proclamation changed how the ongoing imperial conflict developed. The coming war was not just for independence. For many, it would also be a war for emancipation.

The Promise of Freedom

November 1775. A proclamation declaring martial law has been placed in Virginia. Join the community as they confront the choices of an old promise fulfilled.

Sources

- James Corbett David, Dunmore’s New World: The Extraordinary Life of a Royal Governor in Revolution America – with Jacobites, Counterfeiters, Land Schemes, Shipwrecks, Scalping, Indian Politics, Runaway Slaves, and Two Illegal Royal Weddings (University of Virginia Press, 2013), 96.

- Sylvia R. Frey, “Between Slavery and Freedom: Virginia Blacks in the American Revolution,” The Journal of Southern History 49, No. 3 (August 1983), 378; David, Dunmore’s New World, 96 (quote).

- David, Dunmore’s New World, 104-105.

- David, Dunmore’s New World, 103-104.

- David, Dunmore’s New World, 104.

- David, Dunmore’s New World, 101-102

- David, Dunmore’s New World, 105; Rutledge quoted in, Jeremy Engels, Enemyship: Democracy and Counter-Revolution in the Early Republic (Michigan State University Press, 2010), 41-42; London letter quoted in Silvia R. Frey, Water From the Rock: Black Resistance in a Revolutionary Age, (Princeton University Press, 1991), 64;

- David, Dunmore’s New World, 109; Frey, “Between Slavery and Freedom,” 384; Virginia Gazette (Dixon and Hunter), December 2, 1775, p. 3, link; Virginia Gazette (Dixon and Hunter), April 13, 1776, pg. 3, link

- Virginia Gazette (Pinkney), November 23, 1775, p. 2, link.

- Lee quoted in Alan Gilbert, Black Patriots and Loyalists: Fighting for Emancipation in the War for Independence (The University of Chicago Press, 2012), 11.

- David, Dunmore’s New World, 107; Virginia Gazette (Pinkney), December 9, 1775, p. 3, link quoted in Frey, “Between Slavery and Freedom,” 387.

- David, Dunmore’s New World, 107, 122-123, Gary Sellick, “‘Undistinguished Destruction:’ The Effects of Smallpox on British Emancipation Policy in the Revolutionary War” Journal of American Studies 51, No. 3 (August 2017): 365-885.

- David, Dunmore’s New World, 107-108; Frey, “Between Slavery and Freedom,” 388.

- David, Dunmore’s New World, 107, Robert G. Parkinson, The Common Cause: Creating Race and Nation in the American Revolution (University of North Carolina Press, 2016).

- David, Dunmore’s New World, 110-112.

- David, Dunmore’s New World, 122-124.

- Alexander Boulton, “The Declaration of Independence and the Language of Slavery,” Journal of the Early Republic 44, No. 1 (Spring 2024): 1-26.