Custis Square Site

Come and see what's new at Custis Square! Archaeologists are investigating the Williamsburg home of Virginia plantation owner John Custis IV. Visit the archaeological site, see artifacts as they're being discovered, and talk with experts in the field. While you visit, you'll learn about the property's history, from Custis' purchase of the land in the early eighteenth century to its tenure as a recreation space for patients of the Eastern State Public Hospital. Stop by and find out what archaeology can tell us about Custis Square and the people who lived there! This self-guided program is open to visitors of all ages, but children must be accompanied by an adult. Guests may enter the site at the corner of Nassau and Francis Streets. Weather dependent. The terrain is grassy and may be difficult to access by wheelchair.

Excavations at Custis Square

Colonial Williamsburg’s archaeologists excavated the Custis Square site in 1964, 1968, and for a five-year period from 2019 to 2024. Click through to see some of their findings.

John Custis IV and His Garden

John Custis IV was a wealthy man. He inherited a great fortune as a young man, and then married into another wealthy, landowning family. John and his wife Frances Parke had an unhappy marriage. John and Frances had an unhappy marriage. In June 1714, the two signed an unusual document setting out the terms for a truce in their marital disputes.1 After Frances died a year later, John never remarried.2 Near the end of his life, John specified that his gravestone should contain an epitaph noting that he had “aged 71 years, and yet lived but seven years, which was the space of time he kept a bachelor’s house on the Eastern Shore of Virginia.”3

Over the course of his life, Custis enslaved hundreds of people and owned thousands of acres of Virginia land. A member of the colony’s Council and a colonel in the Virginia militia, he was a leading member of the Tidewater gentry. His home and its impressive gardens, on a four-acre lot facing the Governor’s Palace and Bruton Parish Church, were a monument to his elevated status in Williamsburg.

Shortly after moving to Williamsburg, Custis took up gardening. In 1717, he commented, “I have lately got into the vein of gardening.”4 Over the following years, his garden grew in size and ambition. After twenty years of cultivation, he boasted, “I have a garden inferior to few, if any, in Virg[ini]a.”5 Custis’s baroque pleasure garden featured classical statues, gravel walks, topiaries, orchards, vegetable plots, and arbors.

Custis often invited visitors for leisurely strolls through his garden, perhaps pausing to describe a plant or direct one of the enslaved people working in it.6 Recent archaeological excavation suggests that the garden was bordered with a tall fence with two gates, and was likely only accessible from inside the house. It was a private garden, a refuge for the Custis family and favored guests.

Click here to open in a new window.

Enslaved People at Custis Square

Relatively little information survives about the enslaved people who lived in Custis Square. There are a few intriguing details, though. A clause in the 1714 Custis marital agreement (signed before the family relocated to Williamsburg) indicates that Frances would retain the enslaved people “she now hath,” who were “Jenny, Queen, Pompy . . . and also Billy boy or little Roger and Anthony . . . to tend the garden, goe [on errands] or with the coach, catch horses, and doe all other necessary works about the house.”7 We know little else about the enslaved people named in this document. In fact, we don’t even know if Custis brought them to Williamsburg. But this brief passage hints at how the enslaved people in the Custis household might have been caught in the middle of John and Frances’s unhappy marriage.

In his early sixties, Custis fathered a boy named Jack with an enslaved woman named Alice. In 1744, he used his connections to obtain permission from the governor and Council to emancipate Jack.8 Four years later, while “melancholly” at an illness afflicting “my dear black boy Jack,” Custis freed the young man.9 Custis subsequently provided Jack with land, livestock, horses, provisions, an allowance, a furnished home, and ownership of several other enslaved people, including his mother.10 Unfortunately, though, Jack died shortly after inheriting this property.11

In 1745, Custis published an advertisement in the Virginia Gazette seeking the return of a self-emancipated man named Peter. He had fled from Custis’s household with “Irons on his Legs,” in pants fitted with laces on the sides, for “putting them on over his Irons.” The advertisement claimed that Peter was literate and had stolen some money and goods from Custis. After repeated acts of resistance, Custis had “Out-law’d” Peter, meaning that he could be killed on sight.12 It is not known if Peter’s escape was ultimately successful.

Who were Williamsburg’s Enslaved Gardeners?

Early Williamsburg’s gardens, some of the finest in the colonies, would not have existed without the skill and labor of enslaved people.

Custis’s voluminous correspondence about his garden rarely mentions the enslaved people who worked with him to plant and maintain it. In a 1738 letter, Custis vented his frustrations at a deadly drought, which killed many of his plants even though he had directed three “strong” enslaved men to “continually” fill “large tubs of water,” and create artificial shade for the plants.13 As this indicates, the enslaved people who maintained Custis’s garden were often forced to endure hard labor. But from what we know about the garden, we can also conclude that they were highly skilled workers. While Custis himself sometimes got his hands dirty, the bulk of work was done by enslaved people. The garden’s exotic plants, geometric designs, tightly clipped topiaries, and espaliered fruit trees could only come to fruition through the skill of expert gardeners.

Botanical Ingenuity

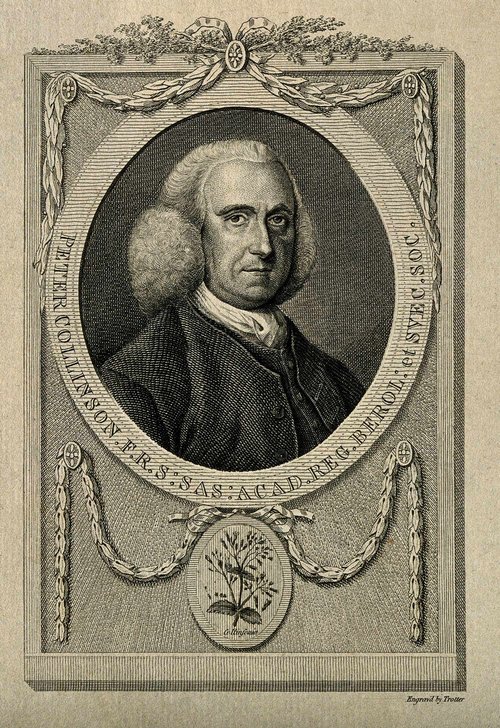

Peter Collinson. Line engraving by T. Trotter, 1783. Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection.

As his garden grew, Custis developed a deep interest in botany. He struck up a long-distance friendship with the London-based naturalist Peter Collinson. They exchanged plants, seeds, and ideas for more than a decade. Their correspondence documents Custis’s efforts to understand Virginia’s plants, climate, and growing conditions. When he received some tuberoses from an English contact, for example, Custis told Collinson about the “severall projects” he undertook to preserve them. He placed some in a warm cellar, he dried others out in a desk drawer, and he left some to “stand in the ground and coverd them with peas straw.” The first two groups died, while the latter survived. Custis concluded “so I find that is the best way to preserve them.”14

Custis’s garden delighted him. He chose plants to cultivate, he wrote, according to “my fancy,” rather than prevailing fashions.15 He hunted after elusive varieties of orchids and lilies. He may have been the first to introduce the rose to Virginia.16 When Collinson sent him a parcel of plants and seeds in 1734, he commented that “20 times the weight of the seeds etc. in gold” would not have pleased him nearly as much.17

But the garden was also a source of immense frustration. Custis was regularly outraged to find that the plants he ordered from England had been poorly packed or mishandled. On one occasion, he learned that “a dog tore” his plants “all to bitts.”18 His efforts sometimes seemed pointless when so many plants died in Virginia’s punishing climate. Thinking about how his plants would “soon whither,” he once lamented to Collinson, “tis all vanity.”19 In 1730, bad weather led him to write to Mark Catesby, another notable English naturalist, that he was “out of heart of endeavoring any thing but w[ha]t is hardy and Virginia proof.”20 Like many gardeners before and since, Custis eventually discovered the benefits of cultivating native plants.

Furber's Flowers

Explore what these iconic prints tell us about John Custis IV when we use art to inform archaeology.

Afterlife

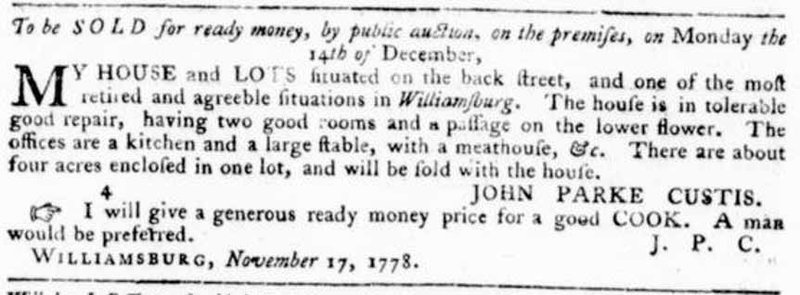

John Custis IV died in 1749. His son and heir Daniel Parke Custis married Martha Dandridge, despite his father’s initial objections, in 1750.21 After Daniel died in 1757, George Washington married Martha Dandridge Custis two years later. On behalf of his new wife and stepsons, Washington took over the management of the Custis lands and houses. He rented out Custis’s Williamsburg properties for several years. In 1778, while Washington was leading the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War, Daniel Parke Custis’s son John Parke Custis convinced him to sell the Williamsburg properties.

With George Washington’s approval, John Parke Custis put the Custis Square land and house for sale in 1778. Virginia Gazette (Dixon and Hunter), Nov. 27, 1778, page 3.

After this sale, the Custis house passed through several hands in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.22 Archaeological dating indicates that the house burned down around 1830. The land subsequently became a recreational yard for patients at the nearby Williamsburg Public Hospital.

Because the land remained relatively undisturbed for decades, its soil has yielded fascinating details about eighteenth-century life on Custis Square. In 1964 and 1968, Colonial Williamsburg archaeologists led by Ivor Noël Hume excavated the site’s cellar, drain, and the foundations of a kitchen and smokehouses. They discovered a well between the house and kitchen that contained artifacts including wine bottles and glasses, children’s spinning tops, and clippings from at least sixteen garden plants.23

In 2019, Colonial Williamsburg archaeologists began a five-year excavation of the site. Using tools and knowledge unavailable at earlier digs, archaeologists focused on understanding Custis’s garden and the enslaved people who built and maintained it. This excavation will result in one of the most accurately recreated eighteenth-century baroque gardens in the United States. According to Public Archaeologist Crystal Castleberry, the new garden will “give us an opportunity to tell the story of the people who were here: the people who made this possible, who lived and worked on it, and visited it. It’s not just about adding another garden to the Colonial Williamsburg roster of eighteenth-century gardens. It’s about making eighteenth-century life more real.”

Click here to open in a new window.

Explore Story Maps

Learn More

Garden Secrets

Archaeological evidence uncovers clues to long-hidden landscape created by John Custis IV.

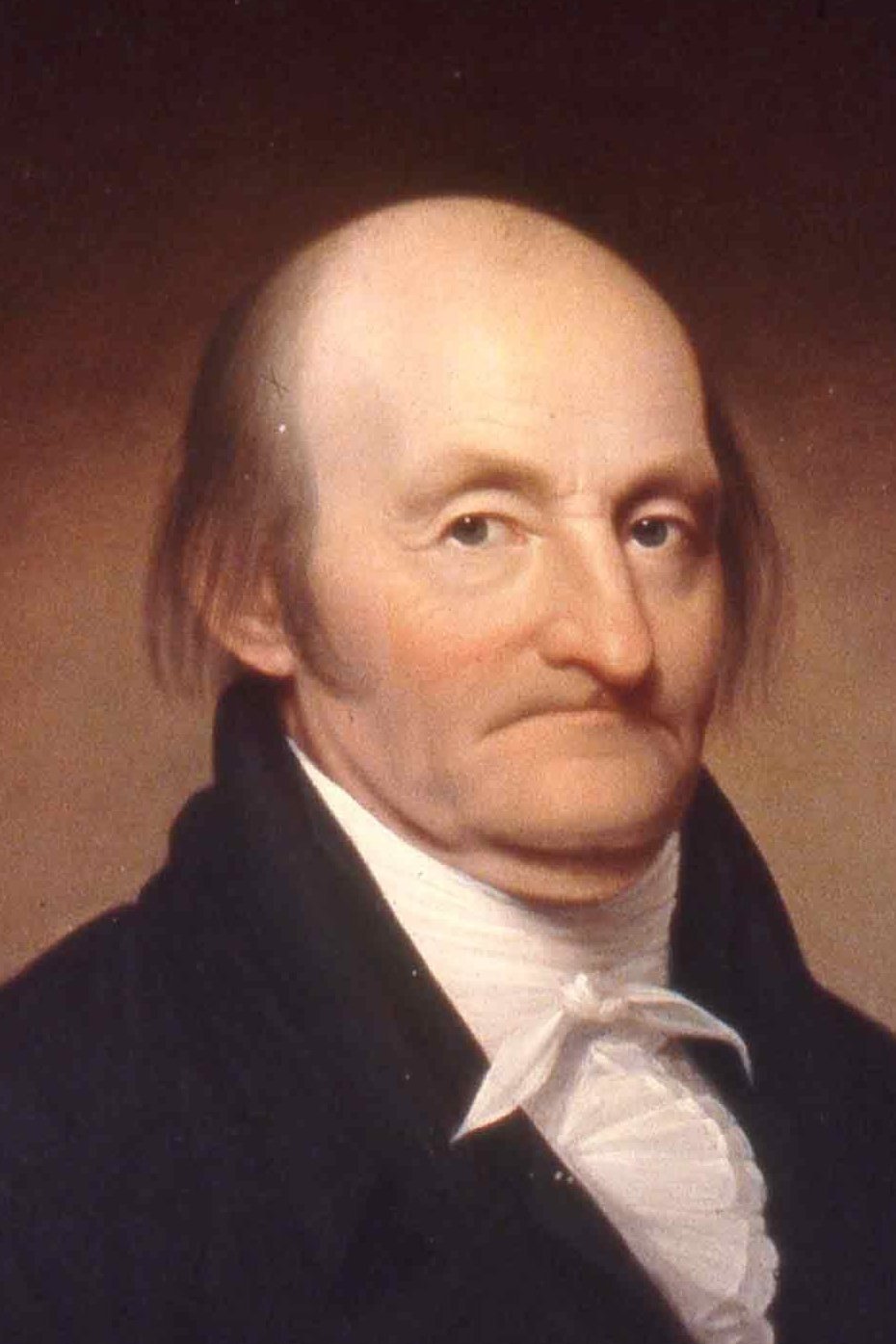

Dr. James McClurg

Though largely forgotten today, Dr. James McClurg was a well-known physician in Virginia during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.He also was a resident at Custis Square during the late eighteenth century.

Custis Square Garden Layout

Explore some incredible discoveries that have helped with the reconstruction of John Custis IV’s early 18th-century garden.

Explore Current Projects

The restoration and preservation of Williamsburg began in 1926 and has been ongoing ever since. Explore some of the projects currently underway.

Sources

- “A Marriage Agreement,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 4, no. 1 (July 1896), 66.

- E. G. Swem, ed., Brothers of the Spade: Correspondence of Peter Collinson of London, and of John Custis, of Williamsburg, Virginia. 1734–1746 (Barre, Mass.: Barre Gazette, 1957), 14.

- Swem, ed., Brothers of the Spade, 16–17.

- Josephine Little Zuppan, ed., The letterbook of John Custis IV of Williamsburg, 1717–1742 (Richmond: Virginia Historical Society, 2005), 35.

- Swem, ed., Brothers of the Spade, 23–24.

- Zuppan, ed., Letterbook of John Custis, 12–13.

- “A Marriage Agreement,” 66.

- Wilmer L. Hall, ed., Executive Journals of the Council of Colonial Virginia (Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1945), 5:141, link.

- John Custis IV to Daniel Parke Custis, Feb. 3, 1747/8, in Jo Zuppan, ed., “Father to Son: Letters from John Custis IV to Daniel Parke Custis,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 98 (Jan. 1990): 99.

- Philip D. Morgan, “Interracial Sex in the Chesapeake and British Atlantic World, c. 1700–1820,” in Sally Hemings & Thomas Jefferson: History, Memory, and Civic Culture, ed. Jan Lewis and Peter S. Onuf (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1999), 52–55; “[Illustration #10]” in “Custis Square Historical Report, Block 4 Lot 1-8,” Colonial Williamsburg Digital Collections.

- Jack’s death is recorded in John Blair’s diary in September 1751. William and Mary College Quarterly Historical Magazine, vol. 7 (Richmond: Whittet & Shepperson, 1899), 152, link.

- “An act for suppressing outlying Slaves,” in The Statutes at Large: Being a Collection of All the Laws of Virginia, from the First Session of the Legislature, in the Year 1619, ed. William Waller Hening (Philadelphia: Thomas Desilver, 1823), 3:86; Thomas D. Morris, Southern slavery and the law, 1619–1860 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996), 341.

- Swem, ed., Brothers of the Spade, 55, link.

- Swem, ed., Brothers of the Spade, 44, link.

- Swem, ed., Brothers of the Spade, 33, link.

- Peter Martin, The Pleasure Gardens of Virginia: From Jamestown to Jefferson (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2001), 57.

- Swem, ed., Brothers of the Spade, 27, link.

- Swem, ed., Brothers of the Spade, 21–22, link.

- Swem, ed., Brothers of the Spade, 75, link.

- Zuppan, ed., Letterbook of John Custis, 109.

- Zuppan, ed., Letterbook of John Custis, 15.

- “Custis Square Historical Report, Block 4 Lot 1-8,” Colonial Williamsburg Digital Collections, p. 31–40.

- Patricia Samford, “Custis Garden Archaeological Report, Block 4,” 1987, Colonial Williamsburg Digital Collections, p. 18.