The Story of Christiana Campbell’s Tavern

Christiana Campbell was one of Williamsburg’s leading late eighteenth-century tavernkeepers. During her time in town, she earned a reputation for keeping an upscale tavern, frequented by some of the leading figures in colonial Virginia.

Who Was Christiana Campbell?

Christiana Burdett was born around 1722, the daughter of a tavern-keeping family.1 Her father John Burdett maintained a tavern in Williamsburg by 1739 until he died in 1746. Christiana administered her father’s will and received an inheritance of 300 pounds and three enslaved people, “Shopshire and Bell with her child.”2 While little is known about her mother Mary, Christiana likely learned the business of tavern-keeping from her. In the eighteenth century, wives and widows played a crucial role in tavern operations—though the business was often under a man’s name.3

Christiana married a doctor named Ebenezer Campbell and left Williamsburg. They had two daughters, Mary and Ebenezer. Their daughter Ebenezer was named for her father, who died in 1752, around the time she was born. After her husband died, Christiana moved back to Williamsburg to open a new tavern by 1755.4 As a widow, she was legally permitted to possess property, and she successfully managed her tavern business for decades.

But like many tavern owners, Campbell experienced a significant downturn in her business after Virginia’s capital moved to Richmond in 1780. While some taverns moved with the capital, Campbell remained in Williamsburg. By 1783, a visitor named Alexander Macaulay found Campbell’s tavern shuttered. When he barged in and demanded to be led into the parlor, he found Christiana Campbell. He described her unkindly as “a little old Woman, about four feet high; & equally thick, a little turn up Pug nose, a mouth screw’d up to one side.” She told him, “I don[’]t keep a house of entertainment, nor have not for some years,” and kicked his party out into the cold.5 Campbell eventually relocated to Fredericksburg, where she died in 1792.6

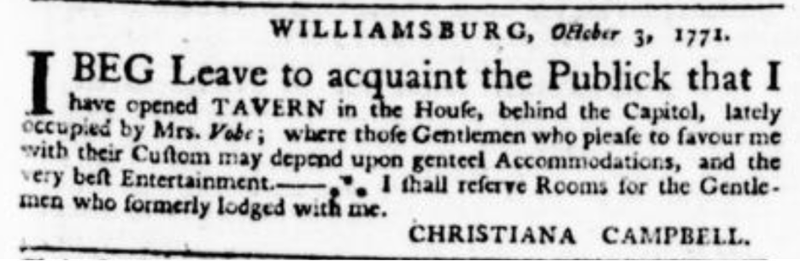

In 1771, Campbell’s Tavern changed locations a few times. She placed this advertisement in the Virginia Gazette to announce where her patrons could find her, and the “genteel Accommodations” she offered. Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon), Oct. 17, 1771, p. 4

What Was Her Tavern Like?

Campbell’s tavern had three documented locations in Williamsburg. In 1760, her tavern occupied a lot where the James Anderson House stands today (familiar to Colonial Williamsburg visitors as the location of the Armoury and Blacksmith trade). Her second location is not precisely known, but in 1771 she moved into a building behind the Capitol previously occupied by Jane Vobe’s tavern (which had previously been a playhouse and a theater).7 This is the present location of the reconstructed Campbell’s Tavern.

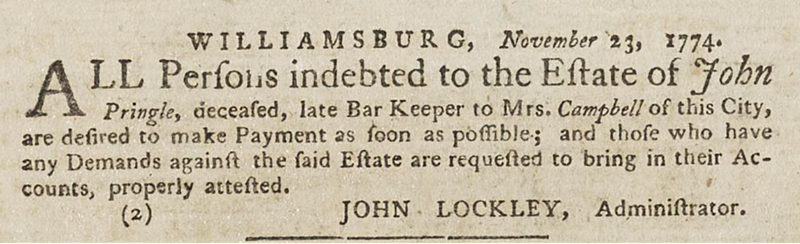

For at least part of the time Campbell’s was open, the bar was kept by a man named John Pringle, whom a November 1774 Virginia Gazette advertisement referred to as “late Bar Keeper to Mrs. Campbell of this City.” Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon), Nov. 24, 1774

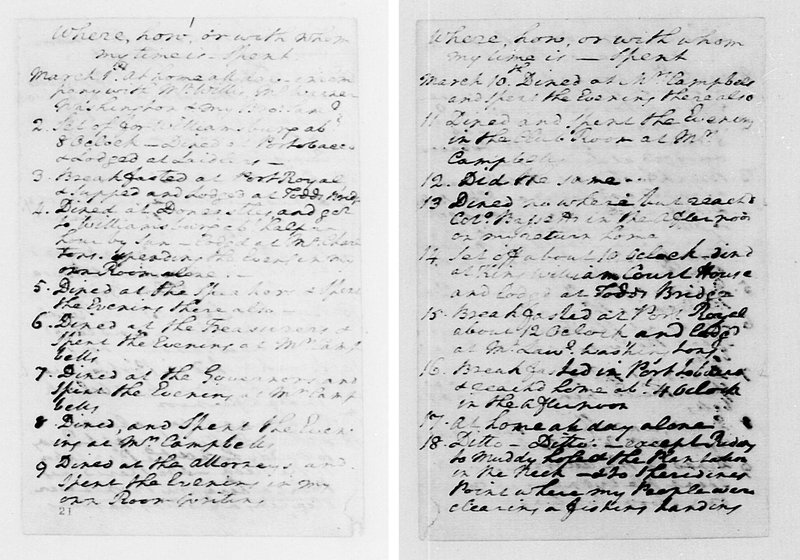

In each of these locations, Campbell’s Tavern was a center of Williamsburg’s social life. People ate, drank, gathered, and played games there. Virginia’s leaders often stayed with Campbell when they assembled in Williamsburg for meetings of the House of Burgesses or the courts. George Washington regularly “Spent the Evening at Mrs. Campbell’s” tavern. Thomas Jefferson similarly noted attending “Mrs. Campbell’s for supper & club.” Like other taverns, Campbell’s provided space for group meetings. The Williamsburg Masonic Lodge regularly met for dinners and balls at Campbell’s Tavern in 1776.8

George Washington’s diary for 1773 indicates that he dined at Christiana Campbell’s on March 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, and 12. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Campbell’s Tavern was large, containing at least eight rooms, three passages, two porches, and a bar. In the 1760s and 1770s, Campbell’s patrons would have taken advantage of the availability of small, private rooms to talk politics. Like many local taverns, Campbell’s was likely a hotbed of revolutionary ideas. While we don’t know much about Campbell’s politics during her life, her tombstone commended her as “An enemy to oppression, A friend to the distressed, The means whose relief she generously exercised and promoted.”9

Enslaved Workers of Campbell’s Tavern

Enslaved workers performed much of the labor that made Campbell’s tavern run. They would have tended to guests’ horses, grown food in the garden, cooked and served food, served alcohol, prepared beds, carted supplies in, and more. Much of Christiana Campbell’s daily life would have involved supervision of these enslaved workers.

We know the names of only a few of the enslaved people who worked at Campbell’s tavern. In 1753, an enslaved boy in Campbell’s household named London was baptized at Bruton Parish Church. London’s entry in the Bruton Parish Church register is also the earliest known evidence of Campbell’s return to Williamsburg following her husband’s death. Parish records also reveal the names of several other enslaved people in the Campbell household: Joseph Fleming, Nelly, Sukey, Sally, Frances, and Sarah.10

Several children enslaved by Campbell also appear in the records of the Williamsburg Bray School, a missionary school for Black children. In 1762, enrollment records indicate that London, Shropshire, and Aggy attended the school. Three years later, Mary and Young were attending. By 1769, Mary had been joined by Sally and Sukey. Given that the Bray School records are sporadic, it is possible that other children from the Campbell household attended as well.11 While this kind of evidence tells us little about the lives of these enslaved people—their personalities, beliefs, or aspirations—they do offer a starting point for further, ongoing research.

What was the Bray School?

The Bray School’s deeply flawed purpose was to convince enslaved students to accept their circumstances as divinely ordained.

While Campbell’s business was winding down in 1783, tax records show that she still enslaved thirteen people.12 That year, the arrival of the unwanted visitor Alexander Macaulay drew the attention of the household’s enslaved people: “we had all the negro’s in the House, about a dozen, around us.”13

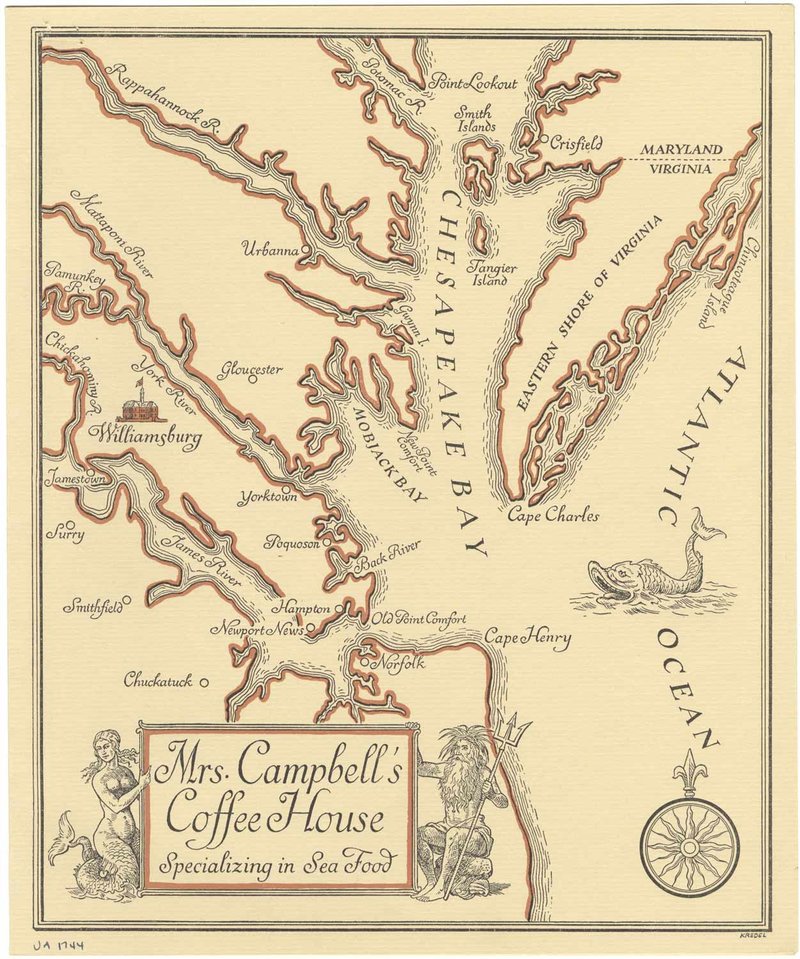

Tavern menu for Christiana Campbell’s (undated, twentieth century), Colonial Williamsburg Corporate Archives.

Afterlife

Following Campbell’s death, the building that had been her tavern passed through the hands of several families. It burned down around 1859. Colonial Williamsburg began work to reconstruct the tavern in 1954. It opened to the public in 1956. As a functioning restaurant, it specializes in seafood, which was served to diners like George Washington in the eighteenth century.

Dine at Christiana Campbell’s Tavern

Step back in time and savor the flavors of history at Colonial Williamsburg’s authentic taverns, each offering a unique glimpse into 18th-century life.

Sources

- Campbell’s tombstone provides the only evidence of her birth year, noting that she died in 1792 at age 70. Dora C. Jett, Minor Sketches of Major Folk and where they sleep: The Old Masonic Burying Ground Fredericksburg, Virginia (Old Dominion Press, 1928), 24, link.

- Mary A. Stephenson and Patricia Gibbs, “Christiana Campbell’s Tavern Historical Report, Block 7 Building 45 y,” (1952, 1975), link

- Sarah Hand Meacham, “Keeping the Trade: The Persistence of Tavernkeeping among Middling Women in Colonial Virginia,” Early American Studies (Spring 2005): 153–54.

- Stephenson and Gibbs, “Christiana Campbell’s Tavern Historical Report.”

- “Journal of Alexander Macaulay,” William and Mary College Quarterly Historical Magazine (Jan. 1903), 187–88, link.

- Jett, Minor Sketches of Major Folk, 24, link.

- Moreau B. C. Chambers, “Christiana Campbell's Tavern Archaeological Report, Block 7 Building 45 Lot 20, 21,” (1955), link.

- Catherine S. Schlesinger, “Christiana Campbell's Tavern Architectural Report, Block 7 Building 45 Lot 21,” (1977), Colonial Williamsburg Digital Collections, link.

- Jett, Minor Sketches of Major Folk, 24-25, link.

- Nicole Brown, “Preliminary Williamsburg Bray School Historical Report, Block 14 Building 41” (2024), Colonial Williamsburg Digital Collections, p. 15–16, link.

- Antonio T. Bly, “In Pursuit of Letters: A History of the Bray Schools for Enslaved Children in Colonial Virginia,” History of Education Quarterly 51 (Nov. 2011): 449; Nicole Brown, “Preliminary Williamsburg Bray School Historical Report, Block 14 Building 41,” Colonial Williamsburg Foundation (2024), 15–16.

- Stephenson and Gibbs, “Christiana Campbell’s Tavern Historical Report,” n.p., link.

- “Journal of Alexander Macaulay,” 187, link.