The King’s Arms Tavern: A History

Located at the eastern end of Duke of Gloucester Street, the King’s Arms Tavern was a center of social life in revolutionary Williamsburg. Operated by Jane Vobe, it was the workplace and home of dozens of enslaved people, including the Baptist preacher Gowan Pamphlet. It was one of the town’s premier taverns, a place where elite Virginians ate, drank, slept, socialized, and more.

Guided by a range of evidence including repair records, insurance policies, and archaeological research, the modern reconstruction of this important historical site captures the refined atmosphere of Vobe’s eighteenth-century business.

Jane Vobe’s Tavern

The King’s Arms was located across from the Raleigh Tavern, near the Capitol building. Before its time as a tavern, this lot passed through several hands: a tailor named James Sheilds, the wealthy plantation owner William Byrd II, and a Glasgow-based mercantile business. By 1760, John Carter was operating a general store on the site.1

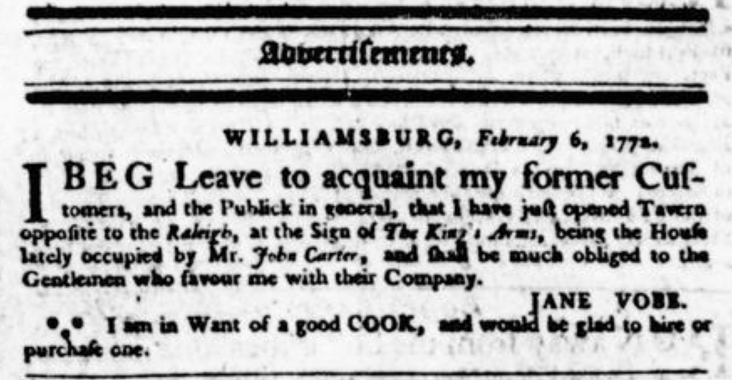

Jane Vobe’s advertisement in 1772 is the first known reference to this building as being located “at the Sign of The King’s Arms.” Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon), Feb. 6, 1772, p. 3

In 1772, the tavernkeeper Mrs. Jane Vobe announced that she had moved her tavern from York Road, behind the Capitol, to the eastern end of Duke of Gloucester Street. By that time, Vobe had become one of Williamsburg’s most successful tavernkeepers. A French traveler had described her earlier tavern as the place “where all the best people resorted.”2 Among the tavern’s visitors were George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, who often dined or attended club there.3

Some college students patronized the tavern as well. In 1779, Robert Carter III wrote to the president of the College of William and Mary to pass along money to pay off “a Balance due to Mrs Jane Vobe” that his son had racked up. Carter insisted that his son “must be confined to the College and to the College Rules.”4 He had apparently fallen into the King’s Arms.

Who was Jane Vobe?

Though easily overlooked today, women like Jane Vobe maintained the institutions where revolution unfolded.

During the time that Vobe kept tavern at the King’s Arms, it was an important Williamsburg landmark. Visitors knew it as “Vobe’s” or “Mrs. Vobe’s.” But after Virginia’s capital moved to Richmond in 1780, business declined significantly. She advertised her tavern for sale or rent in late 1785, and moved her business to Chesterfield County, where she died a year later.5

The King’s Arms and Revolutionary Arms

Though named for Britain’s royal coat of arms, the King’s Arms Tavern was an important site of revolutionary mobilization. In 1774, for example, colonists protesting British policies erected a “large tar mop” and “Bag of feathers” in front of the King’s Arms. According to some witnesses, they used this to intimidate dissenting merchants into signing onto the Continental Association. This event was later immortalized in London, in a print called “The Alternative of Williams-Burg.”6

The Alternative of Williams-Burg Print

Discover the context and details of this famous eighteenth-century print.

During the Revolutionary War, Vobe’s operation helped to supply Patriot armies. In 1781, forces massed in Williamsburg in preparation for what later became known as the Yorktown Campaign. Thomas Nelson Jr., a general in the Virginia militia, ran up a huge tab of more than ninety pounds—a sum suggesting that Vobe supplied a large amount of food, drinks, and lodging for officers and soldiers.7 Baron von Steuben, the Prussian military officer who joined the Continental Army, likewise spent almost $300 at the King’s Arms over four days on lodgings, food, rum, wine, grog, ale, and cider.8 Tavern operations like Vobe’s kept officers and soldiers marching.

King’s Arms Tavern outbuildings, including two privies (in red) and the stables (center).

It also kept them rolling forward. Like many taverns, the King’s Arms operated a transportation business. The stables housed patrons’ horses, and also offered rental carts and carriages. In 1771, Vobe owned “Riding Chairs, both double and single,” as well as a “small Tumbrel” (a kind of cart), “two Carts,” nine cart horses, with plenty of harnesses, saddles, and bridles.9 Records indicate that the King’s Arms supplied transportation services to the Virginia militia and the Caroline County Company of Volunteers.10

What was it like inside the King’s Arms Tavern?

If you walked into Jane Vobe’s establishment, what would you have seen? Who might you have interacted with?

A Time Traveler’s Guide to Early American Taverns

Nowhere better mirrored colonial America’s social complexity than the tavern.

Enslaved Workers

Like most taverns of the era, the King’s Arms relied on enslaved people to function. While we don’t know as much as we would like about the enslaved people whose labor and skill kept Vobe’s tavern operation running, there is more information about these individuals than in many Williamsburg households.

During the time Jane Vobe kept tavern behind the Capitol (later Christiana Campbell’s tavern), she sent two enslaved children named Sal and Jack to the Bray School.16 Sal and Jack likely worked at the King’s Arms Tavern. Based on their education at the school, they might have helped introduce literacy skills to other enslaved members of the Vobe household.

“Aerial view taken by drone of the garden behind the Kings Arms Tavern, May 11, 2022.”

In 1771, Vobe announced a public sale of her possessions (perhaps preparing for her tavern’s move to Duke of Gloucester Street). Among tables, a gold watch, and furniture, she also noted that she was selling “a Negro Woman.”17 When she announced that her establishment was moving to the Duke of Gloucester Street, she also sought a new cook, likely an enslaved woman: “I am in Want of a good COOK, and would be glad to hire or Purchase one.”18 In 1783, tax records listed six people that Vobe enslaved: Sam, Lawrence, Gowen, Mary, Lucy, and Travis. By the next year, her household had added two additional enslaved women, Sylvia and Fanny, as well as two children.19 At the time of her death in 1789, her estate advertised the sale of “two FELLOWS, and a BOY about 17 years old.”20 Little is known about these individuals, but between them, they likely performed tasks such as cooking food, serving patrons, tending stables, cleaning, and washing linens.

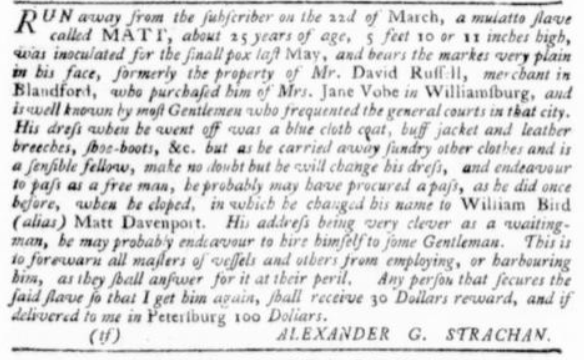

Virginia Gazette (Dixon and Nicolson), April 2, 1779, p. 3

In 1779, a Virginia Gazette advertisement described a twenty-five-year-old enslaved waiting man named Matt as formerly belonging to “Mrs. Jane Vobe in Williamsburg, and is well known by most Gentlemen who frequented the general courts in that city.” Matt may have worked at the King’s Arms, or Vobe’s former location, or at both locations. This example illustrates how enslaved tavern workers came into regular contact with wealthy, powerful guests, even becoming “well known” among them.

Gowan Pamphlet

Likely the most “well known” enslaved worker at the King’s Arms was Gowan Pamphlet. He would go on to become a prominent religious leader, and one of the first Black Baptist ministers in the United States. The first documentary reference to Gowan appears to be a 1779 Virginia Gazette advertisement, which accused “a Negro fellow” named Govn, who belonged to “Mrs. Vobe of Williamsburg” of stealing a horse.21 Whether this documents an actual theft or not is unknown.

Discover the Story of Gowan Pamphlet

Though an enslaved tavern worker, Gowan Pamphlet’s passion was his faith.

Over time, Gowan became a leader in a Baptist Church meeting on the outskirts of Williamsburg. When Vobe moved to Chesterfield County in 1785, near Richmond, he would have accompanied her, disrupting his ability to continue leading his church. Around 1791, he likely returned to Williamsburg with Vobe’s son and heir David Miller. Miller emancipated Gowan two years later. The deed of manumission announced his chosen surname, Pamphlet, which he probably picked to reflect his literacy and intelligence.22 Pamphlet led his congregation to official recognition from other Baptist churches, and led what has become the First Baptist Church of Williamsburg until his death sometime after 1807.23

Reconstructing the King’s Arms

The building housing the King’s Arms Tavern burned down sometime in the first half of the nineteenth century.(24) Using a mix of archaeological evidence, the records of a local contractor, insurance policies, and a contemporary map, Colonial Williamsburg reconstructed the King’s Arms between 1949 and 1953. Today, it remains an operating dining establishment.

Dine at King's Arms Tavern

Step back in time and savor the flavors of history at Colonial Williamsburg’s authentic taverns, each offering a unique glimpse into 18th-century life.

Sources

- Virginia Gazette (Rind), Nov. 29, 1770, link.

- “Journal of a French Traveller in the Colonies, 1765,” American Historical Review 26 (July 1921): 741, link.

- For examples, see George Washington, “Cash Accounts, 1761,” Founders Online; George Washington, “Cash Accounts, October 1763,” Founders Online; George Washington, “Cash Accounts, July 1764,” Founders Online.

- Mary A. Stephenson, “King's Arms Tavern Historical Report, Block 9 Building 29A & B Lot 23” (1949), Colonial Williamsburg Digital Collections, n.p.

- Virginia Gazette and Weekly Advertiser (Nicolson), 10 Nov. 1785, quoted in Stephenson, “The King’s Arms Tavern Historical Report.”

- William Aitchison to James Parker, November 14, 1774, Parker Family Papers, microfilm, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- Journal of the House of Delegates of the Commonwealth of Virginia [1781–1786] (Richmond: Thomas W. White, 1828), 46.

- Stephenson, “King's Arms Tavern Historical Report,” n.p.

- Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon), July 25, 1771, p. 2, link.

- “Virginia Militia in the Revolution,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 15 (July 1907): 92, link; Journal of the Council of the State of Virginia, vol. 1: July 12, 1776–October 2, 1777, ed. H. R. McIlwaine (Richmond: Division of Purchase and Printing, 1931), 127, link.

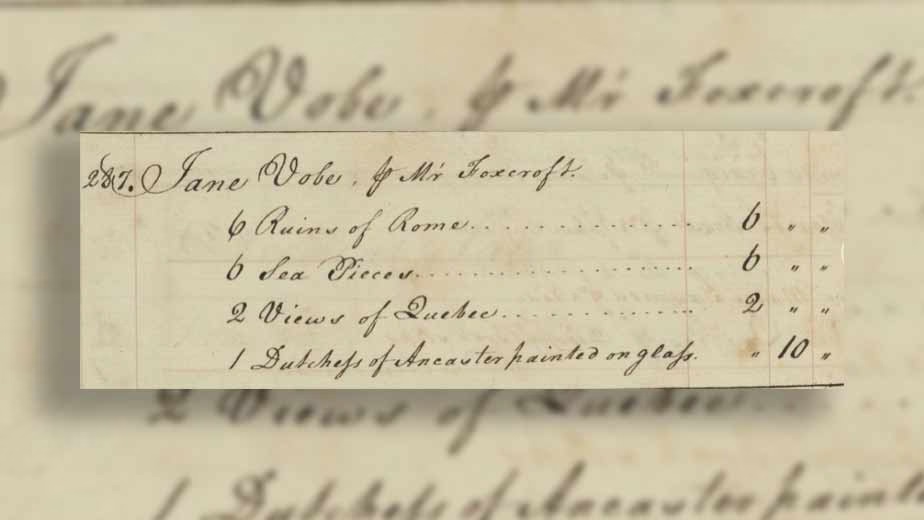

- Virginia Gazette Daybooks, vol. 2: 1764–1766, Feb. 5, 1765, University of Virginia Library, link.

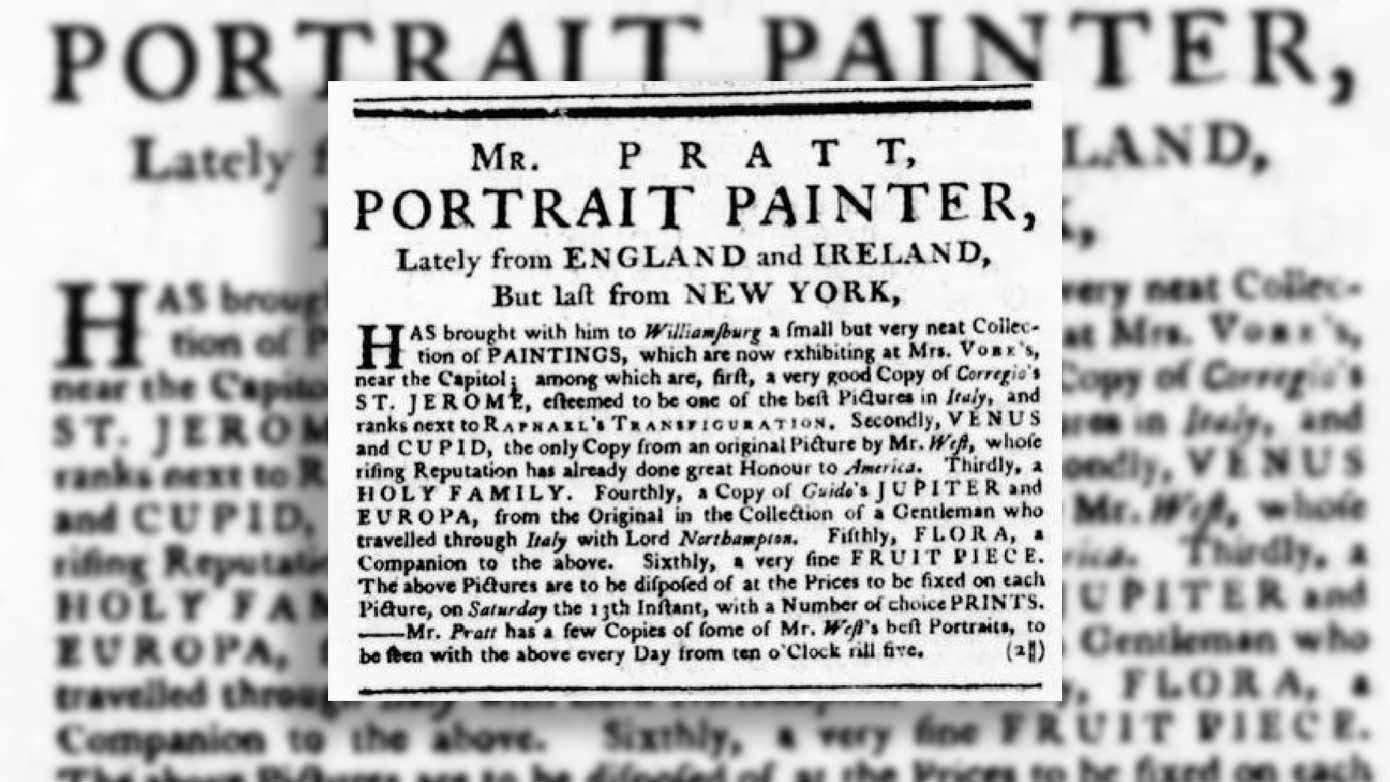

- Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon), March 4, 1773, link.

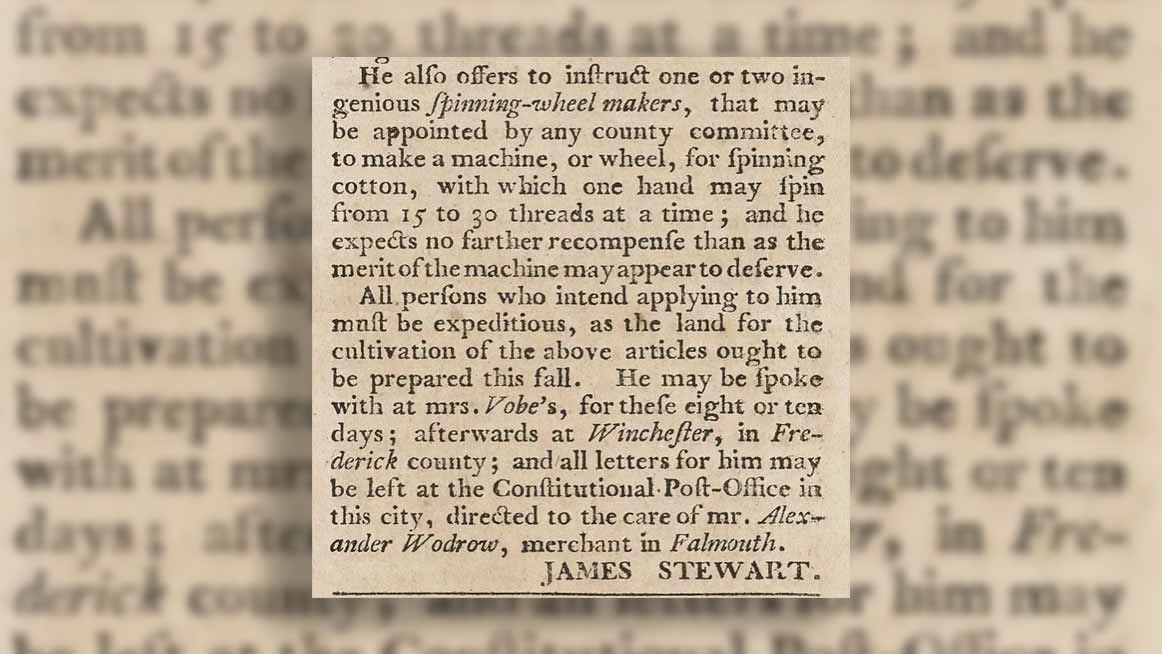

- Virginia Gazette (Purdie), Sept. 15, 1775, link.

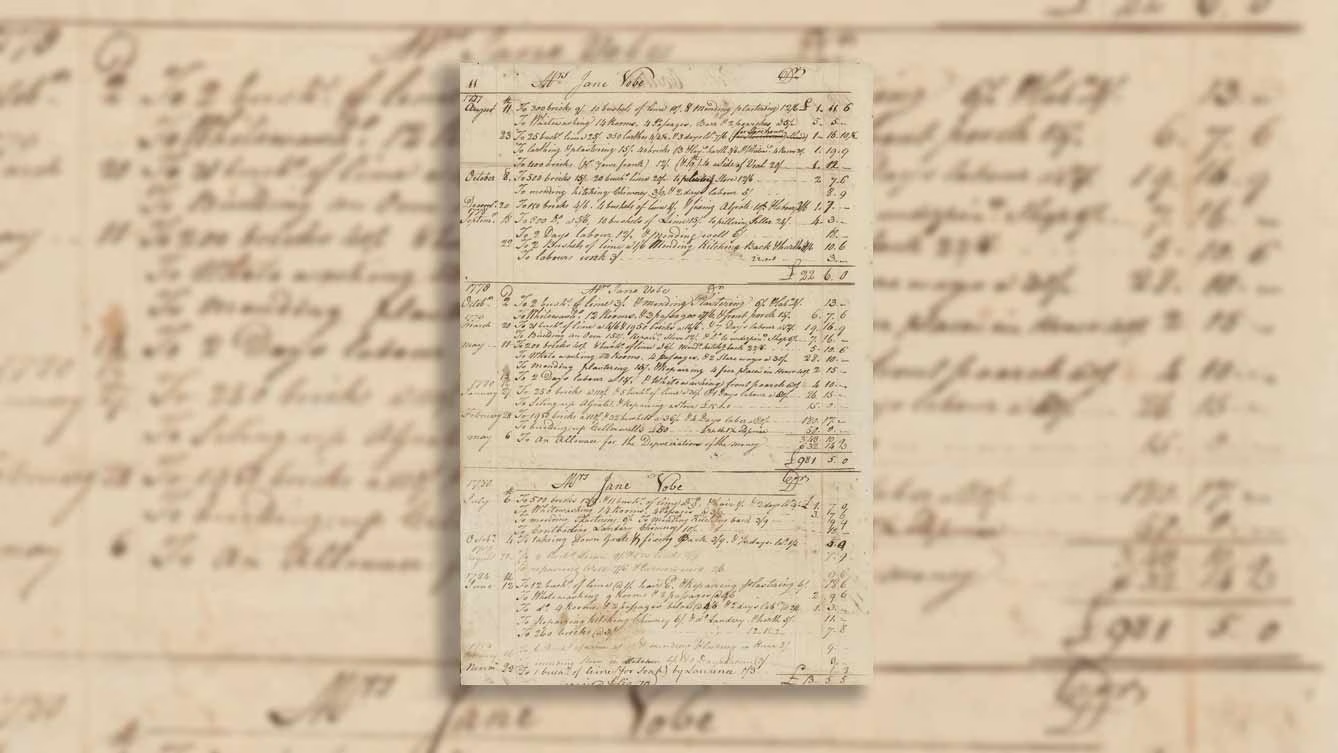

- Humphrey Harwood account book, 1776–1794, Special Collections, John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, p. 11, link.

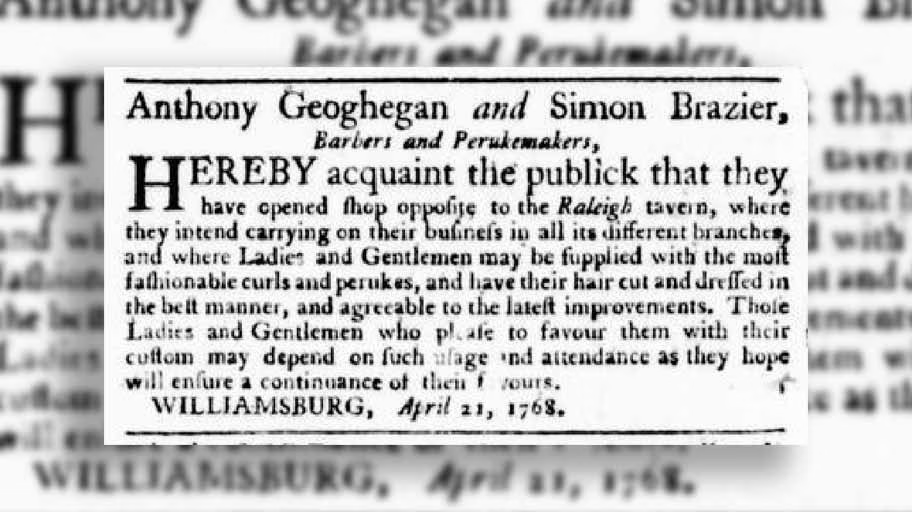

- Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon), April 21, 1768, link.

- John C. Van Horne, Religious Philanthropy and Colonial Slavery: The American Correspondence of the Associates of Dr. Bray, 1717-1777 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1985), 242, 278.

- Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon), July 25, 1771, p. 2, link.

- Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon), Feb. 6, 1772, link.

- Stephenson, “King's Arms Tavern Historical Report,” n.p. Linda Rowe, “Gowan Pamphlet: Baptist Preacher in Slavery and Freedom,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 120 (no. 1, 2012), 19.

- Virginia Independent Chronicle, and General Advertiser, June 24, 1789, quoted in Stephenson, “King’s Arms Tavern Historical Report.”

- Rowe, “Gowan Pamphlet,” 8.

- Rowe, “Gowan Pamphlet,” 16, 23.

- Rowe, “Gowan Pamphlet,” 26.

- Stephenson, “King's Arms Tavern Historical Report,” n.p.