The History and Mysteries of Shields Tavern

The story of Shields Tavern begins with a murder mystery and ends in an alleged criminal conspiracy.

Between these dramatic bookends is the story of two women, a mother and daughter—both named Anne Marot.1 Eighteenth-century taverns were often family businesses, passing from mother to daughter. These two women operated the tavern for most of its history, supervising the labor of dozens of enslaved people and other workers. Their work, skill, and marital decisions tied together the story of this eighteenth-century Williamsburg institution.

William Byrd II, a wealthy Virginia planter, was a frequent patron of Marot’s Ordinary in Williamsburg. His father was also Marot’s first employer in Virginia. Portrait of William Byrd II (ca. 1700–1704). Courtesy of Colonial Williamsburg Art Museums, object no. 1956-561,A&B.

Marot’s Ordinary

Beginning in 1705, a tavern known as Marot’s Ordinary stood near the Williamsburg Capitol. Its location made it an ideal place for the colony’s gentry to congregate, eat, and drink. Visitors enjoyed a greater variety of wines and liquors than anywhere else in town.2 William Byrd II, a wealthy plantation owner and enslaver, often visited “Marot’s” in distinguished company, according to his diary. They drank cider and wine, and ate dishes like goose, roast beef, veal, fish, mutton, and “a good fricassee of chicken.”3

Jean Marot and his wife Anne operated this genteel establishment. Marot was part of a wave of French Huguenot immigrants who settled in Virginia, near Richmond, seeking religious freedom.4 His wife Anne, possibly from a neighboring Huguenot family, played a key role in running the tavern.5 Though little documentation about her exists, Anne was probably the most important figure in the tavern’s history. Eighteenth-century Virginia’s taverns were often licensed in a man’s name, but largely operated by wives and daughters who, among other tasks, helped supervise the labor of enslaved cooks and maids.6

Anne Marot, wife of Jean Marot, may have been from the Pasteur family. Their family Apothecary business was located across the street from Marot’s Ordinary. The Pasteur-Galt Apothecary, seen here, has been reconstructed in Colonial Williamsburg’s Historic Area.

The Murder of Jean Marot

In November 1717, Jean Marot was killed. This was an unusual event in colonial Virginia, especially for a wealthy, white man like Marot.7 Suspicion fixed on Francis Sharpe, a plantation owner whose application for a local tavern license had just been denied. He was held in jail, and a number of respectable gentlemen served as witnesses against him.8 But no trial record survives. Whether he was tried and acquitted, or the charges were dropped, Sharpe was apparently not convicted of murder. The next year, he received a local tavern license.9

Inside a cell at the Public Gaol, where Francis Sharpe was held in 1717.

Lacking further evidence, Marot’s death raises more questions than answers. If Sharpe killed him, was it due to a personal grudge? Was it professional jealousy? We cannot know. But it is clear Marot had made enemies around town. Byrd noted an incident in 1711 when someone threw “a brick from the street” through the window of Marot’s tavern.10 Marot also occasionally ran afoul of the law. Though he was briefly town constable, he was fined for contempt of court and twice for selling liquor above the legal maximum.11

Weddings and Funerals

After Jean’s death, Anne married tavernkeeper Timothy Sullivant and continued to keep tavern in the same location. Since eighteenth-century taverns operated as a partnership between a husband and wife, widow and widowers often remarried within the trade. Over time, Anne likely assumed more legal control of the business. In 1721, she received a license to operate a tavern in her own name, which was unusual for a married woman.12

After Timothy’s death in 1730, Anne ran the tavern under her own name, until she “retir’d to the Country” sometime before 1738, probably to live with her daughter Edith, who was married to a tavernkeeper in Amelia County. She then rented the building to tavernkeeper John Taylor.13 When Anne died in 1742, her daughters inherited the tavern. One of them, Anne, married James Shields (her second marriage, after James Ingles), from another tavern-keeping family. They took over management of the tavern, and it became known as Shields Tavern.

Shields Tavern

Following Jean Marot’s death, the tavern began to serve a broader clientele.14 It also began to struggle. In 1747, the Williamsburg Capitol burned down. The government temporarily met at the College of William & Mary, on the other end of town, which deprived the tavern of its biggest business advantage: proximity to the crowds of hungry and thirsty people attending the assembly and courts.15

In 1748, smallpox struck Williamsburg. Records indicate that 23 members of Shields’s household (mostly enslaved people in all likelihood) recovered from the disease. Another member of the household, described only as a “Negro fellow,” lost his life.16 Perhaps fearing his mortality, James Shields wrote a will. He promised cash bequests to four daughters, but hedged on the amounts. After the destruction of the Capitol building, Williamsburg’s future as the capital of Virginia was uncertain. If Virginia’s capital moved elsewhere, Shields’s property would be less valuable. His will gave his daughters a full bequest if the capital “should not be removed from Williamsburgh” within ten years. If the capital moved, they would only get half of the dollar amount promised.17 Luckily for them, the General Assembly chose to remain for the time being.

Anne Shields’ Tavern

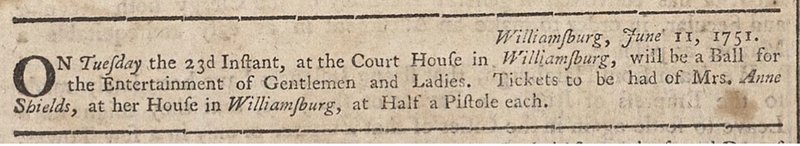

James Shields died in 1750. An inventory of his estate shows a large operation: 14 bedsteads, 60 chairs, and 18 tables, 2 backgammon tables, and a billiard table in the cellar.18 James’s will left “my beloved Wife Anne” the “free Use & Occupation” of the tavern, and she briefly operated it herself. During that time, she also organized a ball at the city’s Courthouse “for the Entertainment of Gentlemen and Ladies.” Not long after the ball, local tavernkeeper Henry Wetherburn’s wife Mary died.19 Ten days after Mary’s death, Anne Shields married Wetherburn.20

Virginia Gazette (Hunter), April 11, 1751

After their marriage, Anne Wetherburn (formerly Marot, Ingles, and Shields) helped manage Wetherburn’s Tavern. She likely organized a series of balls there for visiting Burgesses the next year.21 Little is known of Anne Wetherburn after her final marriage.

Daniel Fisher’s Many Fissures

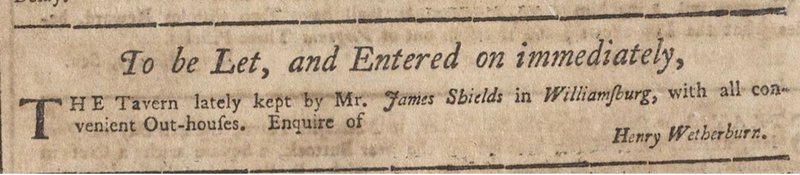

By marrying Henry Wetherburn, Anne lost ownership of Shields Tavern. Under James Shields’ will, if she remarried, her property passed to her son, also named James. Since he was still a minor, his stepfather Henry Wetherburn gained legal control of the tavern.22 He advertised it for rent within weeks. A merchant named Daniel Fisher soon leased it—and came to regret it.

Virginia Gazette (Hunter), August 8, 1751, p. 3

Fisher later wrote a long diary entry detailing his troubled time in Williamsburg. He quarreled with Wetherburn over the terms of the lease, and made enemies with the mayor, a Council member, and many of the town’s most powerful men. They publicly accused him of selling alcohol to enslaved people—a damaging charge for a tavernkeeper. He believed they were trying to drive him out of business and out of town.

Fisher may have been exaggerating, or incorrect, but if anyone was trying to drive him out of business, they succeeded. He abandoned tavern-keeping in 1752, ending more than forty years of tavern-keeping in this property. He divided the building into apartments and pursued his merchant business. But a fire, robbery, and a rift with his wife—all of which he blamed on his enemies—eventually drove him from Williamsburg.23

Slavery and Shields Tavern

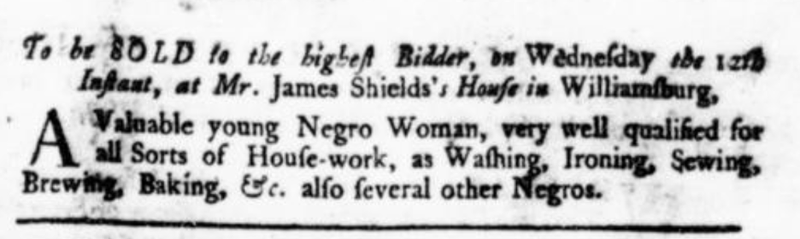

Though their names and stories are largely absent from the written record, enslaved people performed the labor that kept the tavern humming. They prepared, cooked, and served food. They cared for guests’ horses. They likely maintained a kitchen garden, growing fruits and vegetables to be served in the tavern. They carted in supplies and hauled away garbage.

The Shields Tavern garden, where enslaved people likely grew fruits and vegetables for consumption in the tavern.

We know only ten of their names. James Shields’s estate inventory noted that he enslaved 25 unnamed people, most of them working on his plantations. His will named three enslaved individuals—Simon, Belinda, and Juba—left to his stepdaughter Judith. Marot’s inventory named seven enslaved people: “Su & her four Children,” Mary, Jenny, Billy, Nan, Tom Brumfield, and Joseph Wattle. Su and her children were grouped together, suggesting they would be sold together. Others, named and unnamed, were vulnerable to separation from members of their family and community after their enslaver’s death.24

Like many taverns, Shields Tavern was an occasional location for auctions of enslaved people. Virginia Gazette (Parks), June 6, 1745

Reconstruction

Following Daniel Fisher’s disastrous tenure, the building saw varied uses. A blacksmith named John Draper operated there in the 1770s. Dr. John de Sequeyra, a Portuguese-Jewish physician who worked at the Williamsburg Public Hospital, also lived there.25

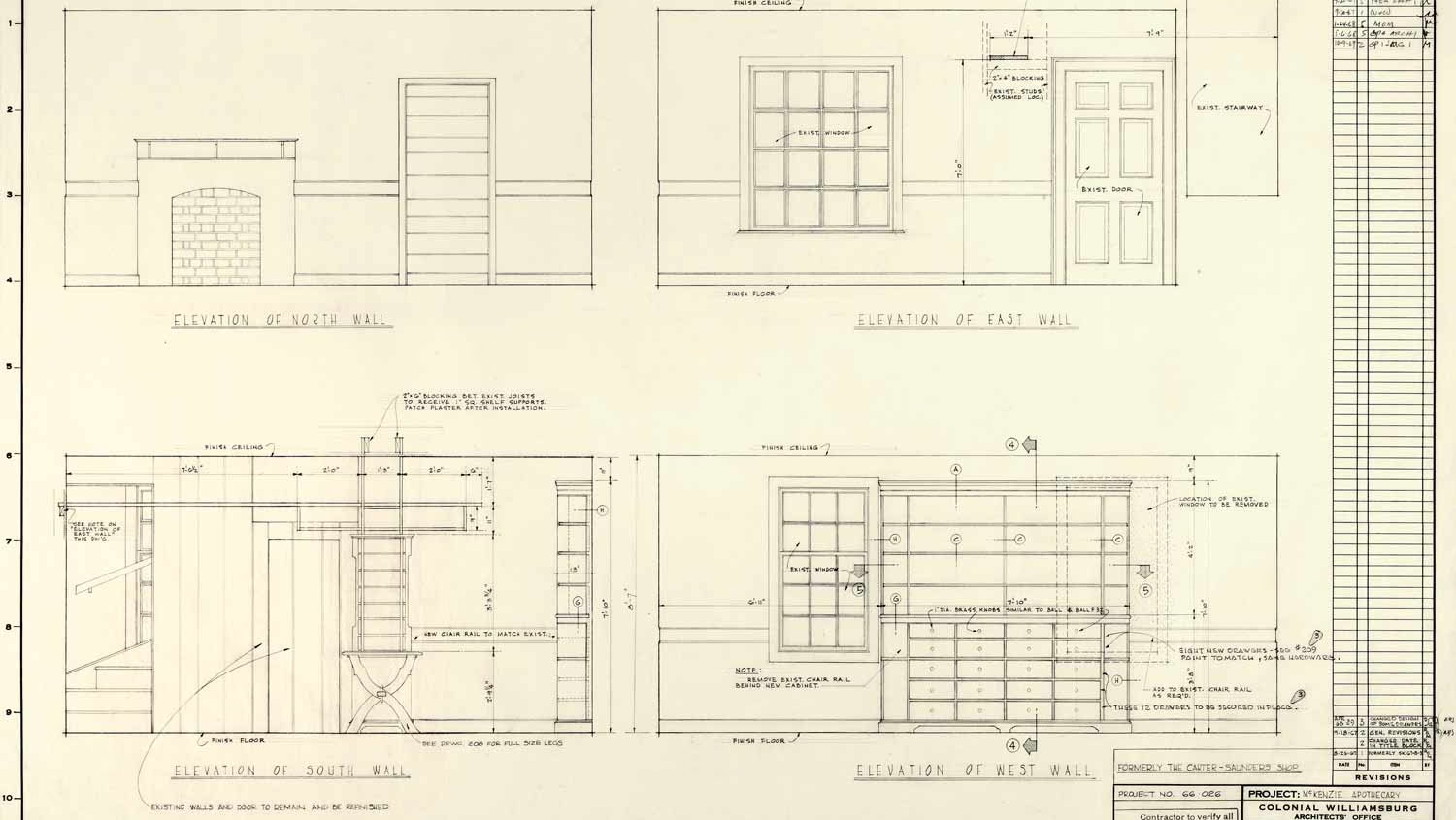

In 1953, the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation initially reconstructed Marot’s Ordinary, and maintained it as housing. In 1988, it reopened as Shields’s Tavern, with the furnishing and reconstruction guided largely by James Shields’s room-by-room estate inventory taken in 1750.26 Today, it continues to function as a tavern restaurant, specializing in fare typical of middling eighteenth-century taverns.

Rebuilding an Eighteenth-Century Tavern

In the 1950s, Colonial Williamsburg excavated the site of Marot’s Ordinary and rebuilt a structure that was used as housing. In the 1980s, Shields’ Tavern became a functioning tavern, with the addition of a large, modern underground kitchen.

Historic Tavern Dining

Step back in time and savor the flavors of history at Colonial Williamsburg’s authentic taverns, each offering a unique glimpse into 18th-century life.

Sources

- In fact, both women had many names, from their several marriages noted here. But each was known, at one time, as Anne Marot.

- Jean Marot’s estate inventory listed two stills, suggesting that some of the tavern’s drinks were distilled onsite. Patricia Gibbs, "Taverns in Tidewater Virginia, 1700-1774," (M.A. thesis, College of William and Mary, 1968), 78–80.

- William Byrd, The Secret Diary of William Byrd of Westover, 1709–1712, ed. Louis B. Wright and Marion Tinling (Dietz Press, 1941), 260, 263, 335, 428 (quote), 434, 435, 438.

- “Shields Family,” William and Mary College Quarterly Historical Magazine 5 (Oct. 1896): 117n1, link; Documents, Chiefly Unpublished, Relating to the Huguenot Emigration to Virginia and to the Settlement at Manakin-Town, ed. R. A. Brock (Virginia Historical Society, 18), 24; “Letters of the Byrd Family,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 35 (July 1927): 241, link.

- One descendant of the Marots wrote that “tradition handed down has it that the family name of Anne, wife of Jean Marot was Pasteur.” See Jean Marot: Huguenot Refugee and Other Allied Huguenot Families, comp. Virginia Lightle Blount (n.d.), p. 5, link. This is plausible given that the Pasteurs were also Huguenots, were neighbors with Marot in Williamsburg (the Pasteur apothecary shop was across from Marot’s home), and evidence survives of at least one property transfer between the families. See Mary A. Stephenson, “Nicolson Store Historical Report, Block 17 Building 4 Lot 56,” Colonial Williamsburg Digital Collections, p. 2, 6, link.

- Sarah Hand Meacham, “Keeping the Trade: The Persistence of Tavernkeeping among Middling Women in Colonial Virginia,” Early American Studies (Spring 2005), 153.

- Randolph Roth, American Homicide (Harvard University Press, 2009), 60–64. At the time of his death, Marot was among the town’s wealthiest residents, leaving behind a sizeable fortune of more than £900. Gregory J. Brown, et al., “Archaeological Investigations of the Shields Tavern Site, Williamsburg, Virginia,” Colonial Williamsburg Research Report (April 1990), 205, link.

- York County Court record for November 18, 1737, York County Orders, Wills, no. 15: 1716–1720, p. 169, available through FamilySearch. Lyon Gardiner Tyler, Tyler's quarterly historical and genealogical magazine, vol. 2, no. 1, p. 271–72.

- Mary E. McWilliams, “Burdett's Ordinary Historical Report, Block 17 Building 2C Lot 58,” Colonial Williamsburg Research Report (1941), Colonial Williamsburg Digital Library, n.p., link.

- Byrd, Secret Diary of William Byrd, 429.

- Hunter D. Farish, “Shields Tavern Historical Report, Block 9 Building 26B Lot 25 & 26,” (1942) Colonial Williamsburg Digital Collections, link; Mary R. M. Goodwin, “Shields Tavern Historical Report, Block 9 Building 26B Lot 25 & 26,” p. 5, link. Gibbs, "Taverns in Tidewater Virginia,” 30.

- Hand Meacham, “Keeping the Trade,” 142, 153–54.

- Advertisement of John Taylor, Virginia Gazette, Sept. 1, 1738, p. 4, link; Patricia A. Gibbs, “Shields Tavern Historical Report, Block 9 Building 26B Lot 25,” Colonial Williamsburg Digital Collections, n.p., link.

- Gibbs, “Shields Tavern Historical Report,” n.p.

- Howard Dearstyne, “The Wren Building of the College of Williams and Mary: Architectural History” (1950), Colonial Williamsburg Digital Collections, link.

- William Quentin Maxwell, "A True State of the Smallpox in Williamsburg, February 22, 1748," The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 63:3 (July 1955), 273.

- Goodwin, “Shields Tavern Historical Report,” appendix, p. xxxv.

- Gibbs, “Shields Tavern Historical Report,” n.p.

- Gregory J. Brown, “Block 9 in the Eighteenth Century: The Social and Architectural Context of the Shields Tavern Property” (1986), Colonial Williamsburg Digital Collections, n.p., link.

- Gibbs, “Taverns in Tidewater Virginia,” 204–5.

- The advertisement read, “For the Ladies and Gentlemen, There will be a Ball, At Henry Wetherburn’s, on Tuesday Evening next, the 10th Instant, and on every Tuesday during the sitting of the General Assembly. Tickets Half a Pistole.” Virginia Gazette (Hunter), March 5, 1752, p. 3.

- Raymond R. Townshend, “Wetherburn’s Tavern Historical Report, Block 9 Building 31 Lot 20 & 21” (1966), Colonial Williamsburg Digital Collections.

- Louise Pecquet du Bellet, Some Prominent Virginia Families, vol. 2 (J. P. Bell Company, 1907), 752–812. Fisher returned to Williamsburg in 1755 to discuss his marriage with his wife, after leaving them behind for Philadelphia. But it’s unclear what happened next, as his journal ends on the road to Williamsburg.

- For Jean Marot’s estate inventory, see Goodwin, “Shields Tavern Historical Report,” link; “An Inventory of the Estate of James Shields deceased,” Colonial Williamsburg Digital Library; Goodwin, “Shields Tavern Historical Report,” n.p.

- Gibbs, “Shields Tavern Historical Report,” n.p.

- Charles Longsworth, “Shields Tavern,” Colonial Williamsburg News, vol. 39, no. 5, May 1986, p. 2, link.

- Gibbs, “Shields Tavern Historical Report,” 10.