The Enslaved People of Williamsburg’s Taverns

The warmth of a tavern beckoned travelers and visitors to rest, eat, and drink. But a tavern’s fire also cast shadows. Denied the comforts of the tavern, enslaved people often occupied these shadows, moving constantly yet often unseen. The story of these taverns is, in large part, their story. The experiences of enslaved people in early Williamsburg’s taverns reveal a powerful resilience in the face of institutions that aimed to control and commodify them—a legacy too often lost in the shadows of history.

Enslaved Tavern Workers

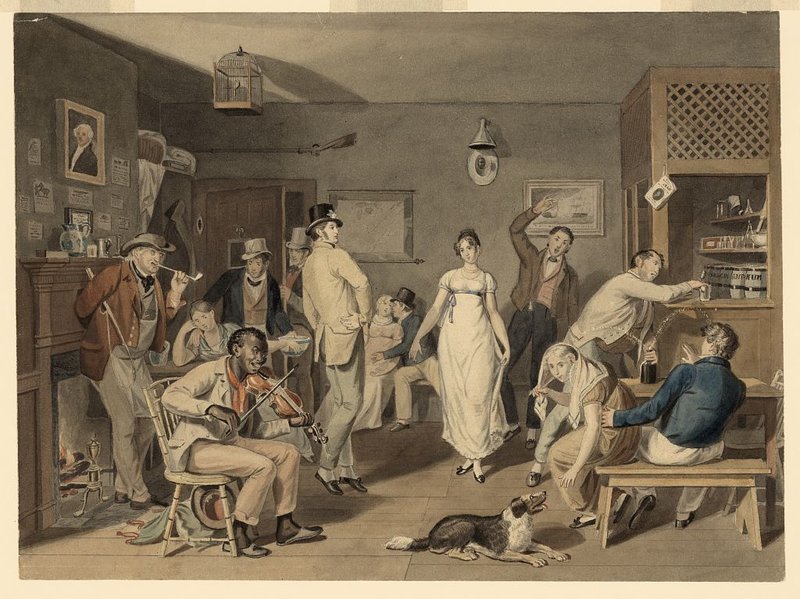

Most Virginia taverns relied on enslaved people to function. While the size of the enslaved workforce varied by tavern, larger operations like the Raleigh Tavern maintained around ten enslaved workers at a time.1 Smaller establishments could manage with just three enslaved workers.2 Enslaved women cooked, cleaned, washed, and ironed. Enslaved men waited tables, cared for horses, drove carts and coaches, and tended gardens.3 They ran errands, like picking up stationery and books from the printer’s shop.4 During balls or other events, enslaved fiddlers entertained patrons. In other roles, especially tending the bar, tavernkeepers tended to employ white workers.5

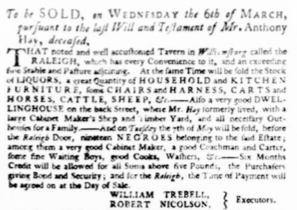

In 1771, the estate of Raleigh Tavern owner Anthony Hay included nineteen enslaved people, including “a good Coachman and Carter, some fine Waiting Boys, good Cooks, Washers,” and others. Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon), Jan. 17, 1771, p. 3

Taverns were important centers of debate and discussion. While serving tables or working around the tavern, enslaved workers no doubt overheard many conversations about people, business, and politics. In the late eighteenth century, with patrons’ voices rising in the night, propelled by rum and revolution, Williamsburg’s enslaved workers had a front row seat to the beginnings of the American Revolution in Virginia.

Many tavernkeepers owned plantations. Some of the foods served in taverns were grown or raised by enslaved people on these nearby farms.6 Business logic often led enslavers to split an enslaved community across multiple properties, which created an important role for those enslaved people who traveled between them. A tavern’s carter not only brought foods from the plantation into town, but also likely carried messages between separated friends and family.

Discover the Story of Gowan Pamphlet

Though an enslaved tavern worker, Gowan Pamphlet’s passion was his faith.

Evidence suggests that tavernkeepers recognized the skill of their enslaved workers. When a tavern owner died, others sometimes sought out the enslaved people who had staffed the business. When Anthony Hay purchased the Raleigh Tavern from William Trebell, the former owner’s wife Sarah Trebell wrote that an enslaved man named Austin “continues” there, and “they have Lydie till after the April court,” presumably to help train the incoming staff of enslaved workers.7

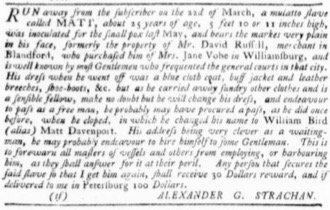

A 1779 advertisement sought an enslaved man named Matt Davenport or William Bird, who had once worked as a waiter at Jane Vobe’s tavern. It noted that he “is well known by most Gentlemen who frequented the general courts in that city.” Virginia Gazette (Dixon and Nicolson), April 2, 1779, p. 3

Patrons took notice of skillful service. In 1783, a German traveler named Johann David Schoepf visited a Williamsburg tavern, probably the Raleigh, and recalled that “Black cooks, butlers, and chambermaids made their bows with much dignity and modesty; were neatly and modishly attired, and still spoke with enthusiasm of the politeness and gallantry of the French officers.”8 Some enslaved people became well known to regular guests. In 1779, for example, an enslaver sought to identify a man named Matt Davenport, who had emancipated himself from slavery. His advertisement described Davenport as “well known by most Gentlemen who frequented the general courts,” because he had worked at Jane Vobe’s tavern.9

Enslaved Peoples’ Tavern Workspaces

Enslaved people kept eighteenth-century taverns running. These are a few of the places where enslaved people worked in the taverns reconstructed in Colonial Williamsburg’s Historic Area.

Taverns and the Slave Trade

Taverns were a key hub in early Virginia’s slave trade. Auctions held at taverns for enslaved people ripped apart families and communities. A man named James, enslaved in Caroline County, Virginia, recorded his memories as a child seeing his eight-year-old sister Judy sold at a tavern. He wrote that a group of “Blood thrusty [thirsty] fellows” gathered to see her, making her “very much a fraid of them.” She “cried very much.” James and his mother begged Landon Carter, his sister’s enslaver, not to sell her far away. Carter promised this, but “as soon as we left him[,] he sold the child” to a man who refused to even say where he lived. James concluded, “we have never heard of the child s[i]nce.”10

Costumed interpreters sit on the porch at the Raleigh Tavern. September 24, 2024

This kind of tragic moment is rarely documented in historical sources. Yet such scenes occurred every time an enslaved person was sold away from family, friends, and a local enslaved community. Virginians often sold and purchased enslaved people at auctions in taverns during the eighteenth century. The Raleigh Tavern, as well as other Williamsburg taverns, regularly hosted such auctions.11

Alcohol and Slavery

In the eighteenth century, nearly all Virginians drank large amounts of alcohol: men, women, and even children. Since water was often unsafe to drink, people enjoyed alcohol at most meals. Few raised moral objections. But there was one big exception: many enslavers tried to control when and how enslaved people drank alcohol. They often only provided alcohol on holidays or during important times in the farming calendar. Enslavers also made it illegal for taverns to serve enslaved people without their permission.12

Early nineteenth-century depiction of a tavern, featuring a Black fiddler performing music. John Lewis Krimmel, [Barroom dancing] (watercolor, ca. 1820). Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

But even so, enslaved people sought places to socialize and drink. Some enslaved people likely spent time in unlicensed taverns, often known as “bawdy” or “disorderly” houses.13 Some licensed taverns may have also illegally sold alcohol to enslaved people. In March 1754, for example, Williamsburg Mayor John Holt publicly accused the tavernkeeper and merchant Daniel Fisher of “selling Rum to Negroes contrary to Law.” In a diary entry, Fisher claimed he had only sold alcohol to enslaved people who had “a written or Verbal leave” from their enslavers.14

Enslaved people found other opportunities to obtain alcohol. By selling chickens and garden produce, or doing extra work on their own time, enslaved people earned money to buy commodities—though often only with an enslaver’s permission. Plantation owner Landon Carter once noted that his enslaved people were “buying liquor with their fowls.”15 A store in Colchester, Virginia, recorded an enslaved man named Jack purchasing rum, food, and household supplies.16 Some enslaved people may have also stolen alcohol from taverns. Court records indicate that in 1750, an enslaved man named Matt was accused of stealing five gallons of wine and ten gallons of rum from the tavern and home of Ann Shields. About six weeks later, a man named Simon, enslaved by Shields, allegedly stole five gallons of rum from the tavern of Jane Vobe. Following the testimony of Vobe and Shields, the court found these men guilty and sentenced them to be hanged—a punishment unlikely for a white defendant convicted of theft.17

Enslaved Spaces

Williamsburg’s taverns embodied the many contradictions of eighteenth-century Virginia society. Tavern-goers relaxed, socialized, played games, and talked politics. But for enslaved people, taverns were workplaces, a place to serve without being served. And for many, taverns might carry grim memories, as places where friends, family, and acquaintances were sold. Enslaved people sustained these community hubs, from cooking and cleaning to waiting and caring for animals. Their work was essential to the comfort and commerce of colonial life.

A Time Traveler’s Guide to Early American Taverns

Nowhere better mirrored colonial America’s social complexity than the tavern.

Sources

- “Enslaving Virginia,” Colonial Williamsburg research report (1998), p. 632; Patricia Gibbs, “Taverns in Tidewater Virginia, 1700-1774,” (M.A. thesis, College of William and Mary, 1968), 48–50.

- Pat Gibbs, “Shields Tavern Historical Report, Block 9 Building 26B Lot 25” (1986), Colonial Williamsburg Digital Collections, n.p.

- “Enslaving Virginia,” 626.

- “Enslaving Virginia,” 628.

- Gibbs, “Taverns in Tidewater Virginia, 1700–1774,” 47.

- Sarah Hand Meacham, “Keeping the Trade: The Persistence of Tavernkeeping among Middling Women in Colonial Virginia,” Early American Studies (Spring 2005): 149, 160.

- “Enslaving Virginia,” 628–32.

- Johann David Schoepf, Travels in the Confederation [1783–1784], trans. Alfred J. Morrison (Philadelphia: William J. Campbell, 1911), 2:81.

- Virginia Gazette (Dixon and Nicolson), April 2, 1779, p. 3, link.

- Linda Stanley, “Notes and Documents: James Carter's Account of His Sufferings in Slavery,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 105 (July 1981): 337, link.

- On the Raleigh Tavern, see, for example, advertisement signed John Thompson, Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon), Dec. 4, 1766, p. 3, link; Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon), Feb. 5, 1767, p. 3, link; Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon), April 2, 1767, p. 3, link; advertisement signed John Camm and James Carter, Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon), Oct. 7, 1773, p. 2, link; Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon), Feb. 17, 1774, p. 3, link. On John Taylor’s tavern, see Virginia Gazette (Parks), Oct. 24, 1745, p. 4, link; on Maupin’s tavern: Virginia Gazette (Dixon and Hunter), Feb. 25, 1775, p. 3, link; on Vobe’s tavern, see Virginia Gazette (Parks), March 28, 1745, p. 4, link.

- Sarah Hand Meacham, Every Home a Distillery: Alcohol, Gender, and Technology in the Colonial Chesapeake (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013), 19–22.

- Vaughn Scribner, Inn Civility: Urban Taverns and Early American Civil Society (New York University Press, 2019), ch. 4.

- Louise Pecquet du Bellet, Some Prominent Virginia Families, vol. 2 (J. P. Bell Company, 1907), 778.

- Meacham, Every Home a Distillery, 20.

- “Enslaving Virginia,” 373–74.

- Linda Sturtz, Within Her Power: Propertied Women in Colonial Virginia (Routledge: 2002), 99–101.