Who Were the Native Peoples of Tsenacommacah?

The land generally known as Virginia today has been inhabited by Native people for many centuries. The Algonquian speaking peoples of the Powhatan Paramount Chiefdom knew this land as Tsenacommacah (and other spelling variants, such as Tsenacomoco), meaning “densely inhabited land.” Their descendants still live in the region today.

Peoples and Populations

Thousands of Native peoples lived in Tsenacommacah, largely in settlements along waterways and the coast. It is challenging to determine population numbers precisely, because of rapid demographic changes caused by colonialism, ongoing migrations, and a lack of records. Moreover, by the time English colonists arrived in Tsenacommacah in 1607, Native populations were already declining due to the spread of disease from earlier contacts with Europeans. Estimates of Indigenous populations in eastern Virginia at the beginning of the seventeenth century range from as few as 13,000 to as many as 30,000.1 Whatever the exact figure, they would have outnumbered European settlers for many years.

At the time of English arrival, most of these Indigenous people belonged to dozens of Algonquian-speaking chiefdoms that paid tribute to the Powhatan Paramount Chiefdom. Among these were the Pamunkey, Arrohateck, Appamatuck, Nansemond, Kiskiack, Paspahegh, Rappahannock, and Mattaponi peoples. Not all Indigenous nations were part of the Powhatan Paramount Chiefdom. The independent Chickahominy nation lived in lands surrounding the Chickahominy River.2 Over time, the impact of colonialism caused many chiefdoms to reorganize, combine, or migrate. Facing an onslaught of war, enslavement, and disease, the Native population of Tsenacommacah declined significantly in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.3 But Native peoples continued to be an important force in the region’s military conflicts, commerce, and diplomacy.

The American Indian Encampment

Visit an interpretive camp of a small American Indian delegation in Williamsburg.

The Economy of Tsenacommacah

In the eighteenth century, the Native peoples of Tsenacommacah gathered food in much the same way Europeans did: farming (including the nutritious trio of corn, beans, and squash), raising livestock, gathering edible plants, fishing, and hunting (often using fire to drive deer toward hunters). Their diet often varied according to the season, allowing them to use resources when they were abundant.4 Like colonists, they also preserved food during its offseason. But arriving colonists often built settlements in coastal areas and places with rich farmland, disrupting Indigenous foodways.5

The region’s Native inhabitants engaged in long-distance trade across North America with other Indigenous nations, exchanging items such as red copper and shell beads.6 The arrival of European colonists created opportunities for new forms of exchange. Native people hunted deer and other animals and traded their skins for European goods.7 By the eighteenth century, the city of Williamsburg became a regional hub of exchange between the European and Indigenous economies. Native people were regular participants at the Market House at the center of town.

Government and Politics

Native polities in Tsenacommacah had diverse and complex governments. The Powhatan Paramount Chiefdom, which existed in the early seventeenth century, was led by a leader, known as mamanatowick, named Powhatan. Local leaders, known as weroances or weroansquas, received tribute from their people and paid some of that tribute to the mamanatowick.8 Tribute, such as corn, deerskin, and pearls, provided leaders with prestige, power, and items that they could exchange with Europeans.

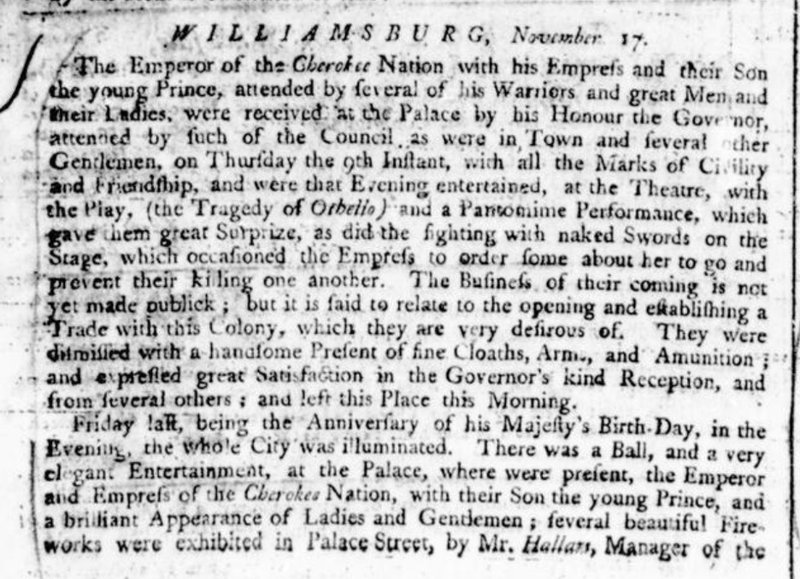

Williamsburg’s newspaper recorded the visit of a Cherokee delegation in 1752. Virginia Gazette (Hunter), Nov. 17, 1752.

A series of conflicts in the early seventeenth century, known as the Anglo-Powhatan Wars, rearranged the political map. In 1646, many members of the Powhatan Paramount Chiefdom signed a treaty that ended these wars. Its signatories became tributary tribes to the English Virginians. They provided loyalty and regular tribute payments in exchange for protection and respect for their territorial rights. The 1677 Treaty of Middle Plantation, signed at a European settlement where Williamsburg would eventually be built, solidified this status. Many other independent tribes remained in the region and regularly sent delegations to Williamsburg to discuss matters of trade, diplomacy, and war. Groups of Indigenous visitors regularly encamped in Williamsburg, including on the green in front of the Governor’s Palace.

Attakullakulla

Cherokee diplomat Attakullakulla traveled many times to Williamsburg over the years, helping to open up trade between the Overhill Cherokee people and the Virginia settlers.

Captivity, Slavery, and Freedom Suits

As Virginia colonists gained power in Tsenacommacah in the seventeenth century, they began to enslave Native people. Many enslaved Native people were taken as war captives, either by the Virginians or their Native allies.9 By the late seventeenth century, to avoid rifts with local tributary tribes, Virginians generally preferred to purchase enslaved Indigenous people from other colonies. They also sometimes sold local captives to other colonies, including Caribbean islands.10

The Brafferton Indian School

At the Brafferton Indian School, colonists attempted to teach Native boys English language, religion, and culture. Today, it remains as a monument to the resilience of Native people.

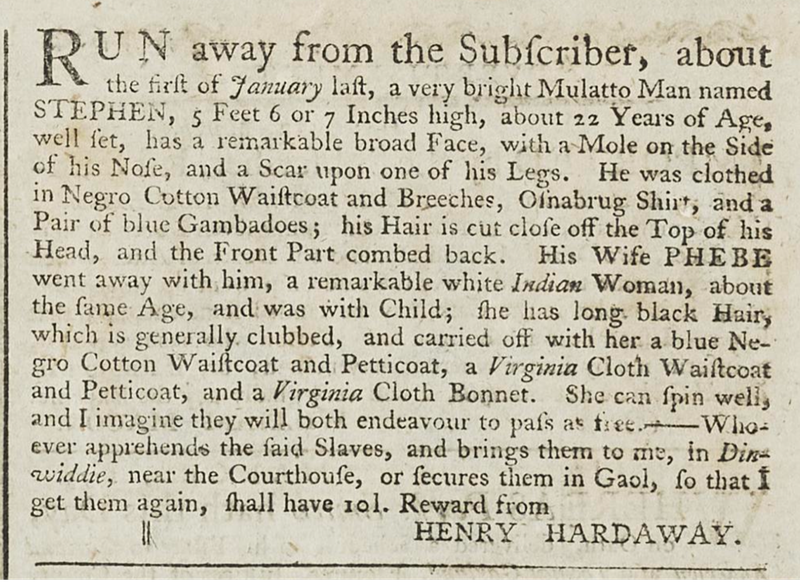

As African slavery grew, the Indian slave trade declined. Virginia’s legislature outlawed the enslavement of Native people in 1691, but this prohibition was not fully enforced.11 Evidence, such as advertisements in the Virginia Gazette, suggests that Native people continued to be enslaved through the eighteenth century.

This advertisement describes a woman named Phebe who ran away from Henry Hardaway as “a remarkable white Indian Woman.” Hardaway noted that she and her husband, “will both endeavour to pass as free.” Virginia Gazette (Dixon and Hunter), March 25, 1775.

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, enslaved people of Indigenous descent began to sue for their freedom, citing the earlier prohibition combined with the legal precedent that a person inherited the status of their mother. An enslaved person could be freed in court if they proved that their mother, or a maternal ancestor, was a free Native woman. Such cases would have been regularly heard in county courts as well as in the General Court in Williamsburg’s Capitol.12

Aaron Griffin’s Search for Freedom

An enslaved man named Aaron Griffin, and many others, sued for his freedom in 1770, likely based on a claim of Indigenous heritage.

Legacy

Virginia’s Native peoples have survived centuries of warfare, land loss, and disease. Today, thousands of people of Indigenous descent still live in the region. Virginia recognizes eleven distinct tribes today. The Pamunkey and Mattaponi Tribes continue to live on reservations within Virginia that they have inhabited continuously since the mid-seventeenth century. Native people have never left Tsenacommacah, but have adapted to a changing world.

Watch the Video

Sources

- For estimate of 13,000 see Martin Gallivan, “Overview of the Powhatan Chiefdom,” in A Study of Virginia Indians and Jamestown: The First Century (National Park Service, 2005), ch. 3. For an estimate of “at least fourteen thousand Algonquian speakers in 1607–1608,” see Helen C. Rountree, Pocahontas’s People: The Powhatan Indians of Virginia Through Four Centuries (University of Oklahoma Press, 1990), 3. James D. Rice estimates “More than thirty thousand Native people lived in the Chesapeake region when the Jamestown colonists arrived.” James D. Rice, “Escape from Tsenacommacah: Chesapeake Algonquians and the Powhatan Menace,” in Peter C. Mancall, The Atlantic World and Virginia, 1550–1624 (Omohundro Institute of Early American History & Culture, 2007), 102.

- Rountree, Pocahontas’s People, 10.

- Peter H. Wood, “The Changing Population of the Colonial South: An Overview by Race and Region, 1685–1790,” in Powhatan’s Mantle: Indians in the Colonial Southeast, ed. Gregory A. Waselkov, Peter H. Wood, and Tom Hatley (University of Nebraska Press, 2006), 64.

- Martin D. Gallivan, The Powhatan Landscape: An Archaeological History of the Algonquian Chesapeake (University Press of Florida, 2016), 76.

- Rountree, Pocahontas’s People, 67.

- Gallivan, Powhatan Landscape, 32–33, 38, 163; Rountree, Pocahontas’s People, 132.

- Rountree, Pocahontas’s People, 145.

- Rountree, Pocahontas’s People, 9.

- Christina Snyder, Slavery in Indian Country: The Changing Face of Captivity in Early America (Harvard University Press, 2010), 46, 49.

- C. S. Everett, “‘They shalbe slaves for their lives’: Indian Slavery in Colonial Virginia,” in Indian Slavery in Colonial America, ed. Alan Gallay (University of Nebraska Press, 2009), 70–71, 97.

- William Waller Hening, ed., The statutes at large; being a collection of all the laws of Virginia, from the first session of the legislature, in the year 1619, vol. 1 (R. & W. & G. Bartow, 1823), vi–vii.

- Thomas Jefferson, Reports of Cases Determined in the General Court of Virginia: From 1730, to 1740; and From 1768, to 1772(Charlottesville: F. Carr, and Co., 1829), 116; Honor Sachs, “’Freedom By A Judgment’: The Legal History of an Afro-Indian Family,” Law and History Review 30 (2012), 173–203.