John Custis IV

The life of John Custis IV shows that neither money nor power can buy happiness.

Courtesy of Museums at Washington and Lee University, Lexington, Virginia.

John Custis IV was one of colonial Virginia’s wealthiest men. His fortune came from the labor of hundreds of enslaved people, whose names and stories are largely unknown today. These individuals grew tobacco on Custis’s vast tracts of land. Custis acquired this land and the people enslaved on it through an inheritance, a financially advantageous marriage, and his own business savvy. His wealth and social standing won him a seat on Virginia’s powerful Council, where he served for decades. Over his long life, he became one of Williamsburg’s most prominent residents.

But the things that enriched and empowered John Custis IV also entangled him in lengthy legal disputes, political rivalries, and a famously difficult marriage. His surviving letters display a hot-tempered man who was quick to complain and slow to trust. Looking back on his happy childhood and unhappy adulthood, late in life he directed that his tomb in Arlington, Virginia, display an inscription noting that he died “aged 71 years and yet lived but seven years which was the space of time he kept Batchelors house at Arlington on the Eastern Shoar of Virginia.”1

Visit Williamsburg’s Custis Square

Archaeologists have excavated Custis’s Williamsburg lot to learn more about the Custis family, the people they enslaved, and others who inhabited this land.

Early Life and Marriage

John Custis IV (hereafter referred to simply as “Custis”) was born in 1678 to a prominent family of plantation owners. While little is known about his early years, his epitaph indicates that he cherished a period of life when he lived independently. His grandfather John Custis II, whom he may have been close with, helped to fund a journey for the young man to England. There he learned the tobacco trade from London merchants and probably received some formal education.2

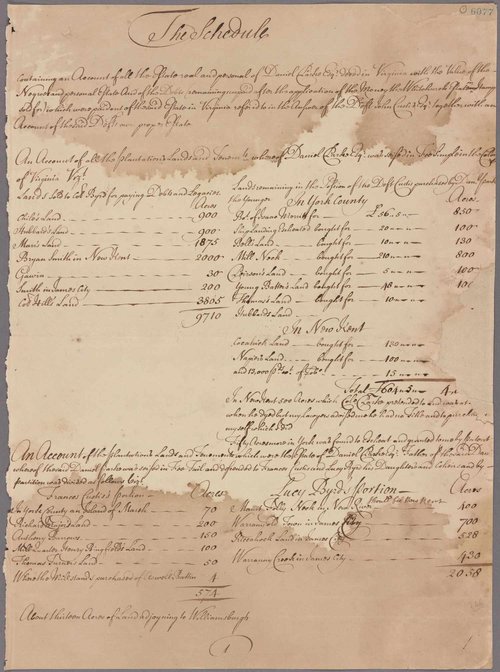

This 1750 document marks the disposition of the estate of Custis’s father-in-law Daniel Parke II. Beginning with Parke’s death in 1710, legal wrangling over this estate continued long past John and Frances Custis’s deaths. Much of the estate was eventually sold to cover the debts of the deceased. Courtesy of New York Public Library Digital Collections.

In 1706, Custis married Frances Parke, daughter of Daniel Parke II and Jane Ludwell Parke. It was a financially prudent match as it brought him land and powerful connections to influential families. Our most intimate portrait of their marriage comes from the diary of Custis’s closest friend and brother-in-law William Byrd II, who married Frances Parke’s sister Lucy on the same day. According to Byrd, the union may have begun on good terms. In 1709, for example, Byrd described an enjoyable visit with another family: “the women went to romping [meaning rude, noisy, or boisterous play] and I and my brother Custis romped with them.”3 But Byrd also noted signs of trouble in the Custis marriage, including disagreements about where they would live and how Frances’ inheritance would be used.4

In 1712, Byrd noted that Frances complained of “the unhappy life she led” due to Custis’s “unkindness.”5 By June 1714, John and Frances decided to end “all animostys and unkindness” between them. They negotiated the terms of a formal agreement. Frances would no longer call “John any vile names or give him any ill language.” She also agreed to return “all the money, Plate and other things whatsoever that she hath taken from him.” For his part, Custis promised not to sell household items without her consent and to increase Frances’s allowance. She agreed not to “run him in debt.” They divided up their affairs so that Frances would run the household, while John would manage the business. Even the household’s enslaved people were divided between them and assigned specific duties.6

If this agreement had an impact on their marriage, it was brief. Frances died of smallpox a few months later and Custis never remarried. A few months after Frances’s death, he wrote a letter to Byrd and joked that, because he had not heard from him, he worried that he was “dead (or what is worse) married.7

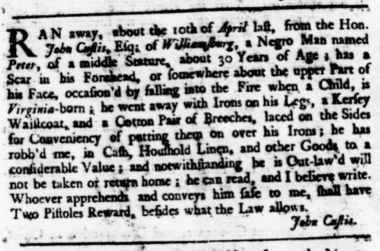

This advertisement placed by Custis describes a self-emancipated man named Peter escaping bondage “with Irons on his Legs.” Virginia Gazette (Parks), May 9, 1745, p. 4.

Slavery

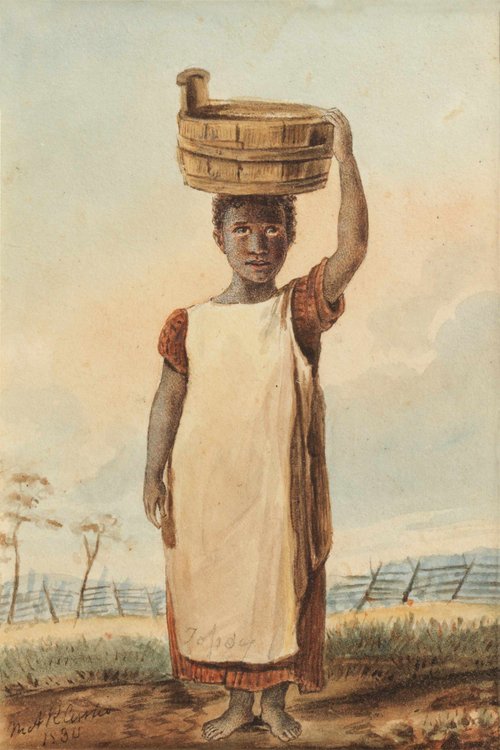

This nineteenth-century image depicting an enslaved child was drawn by Mary Randolph Custis, a descendant of John Custis IV. “Portrait of an Enslaved Girl” (1830), water color. Courtesy of Colonial Williamsburg Art Museums. Object no. 2007-34,1.

Custis enslaved hundreds of people across his plantations. Despite spending most of his days surrounded by these enslaved people, he rarely wrote about them. As a result, relatively little is known about most of them.8 His 1714 marriage agreement with Frances lists enslaved people in its division of household responsibilities: Jenny, Queen, and Pompy would work in the house, while “Billy boy or little Roger and Anthony or such another” would “tend the garden, goe of errands or with the coach, catch horses and doe all other necessary works about the house.”9

How did Custis control his enslaved workforce? Like other Virginia plantation owners, Custis relied on overseers, but did not hesitate to use fear and violence to maintain control. In 1745, for example, Custis placed an advertisement in the Virginia Gazette seeking to recapture a self-emancipated 30-year-old enslaved man named Peter. Custis noted that Peter escaped “with Irons on his Legs” and pants fitted with laces to allow them to cover his irons. Custis described Peter as “Out-law’d,” wording that informed others that Peter could be killed on sight.10

A 1732 letter reveals a similar mindset. He had promised to watch John Randolph’s plantations while he traveled to England. His letter to Randolph noted that an enslaved man named Simon had run away, “haveing a notion that he had no master,” in Randolph’s absence. Custis wrote that he “went immediately up; and undeceived him to his cost,” indicating that he attacked or otherwise coerced Simon on Randolph’s behalf.11

Daniel Parke Custis. Courtesy of New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Fanny and Daniel

John Custis IV’s marriage with Frances Parke Custis produced two children who survived to adulthood: Frances (known as Fanny) and Daniel. Custis appears to have been a devoted father, but he was often frustrated by his children’s romantic choices.

Fanny fell in love with a ship captain named James Bradby around 1731. Custis reluctantly agreed to the match, providing a generous dowry. But Bradby broke off the engagement just before the wedding. Custis denounced him as a “rascal” to a London merchant who employed Bradby, likely to exact some revenge.12 Fanny then married a merchant named William Winch, who later complained that his new father-in-law “absolutely refused” to pay for her dowry. Winch cut Fanny out of his will in retaliation.13 After his death, Fannie married a ship captain named Thomas Dansie. She died in 1744.14

John Custis’s only son and principal heir was Daniel Parke Custis. He was expected to marry well to ensure the Custis family legacy. Daniel considered a few options, but eventually settled on Martha Dandridge, who was twenty years his junior. Though his father considered Martha to be “beautifull & sweet temper’d,” he initially opposed the match, likely because she came from a family that was inferior “in Point of Fortune.” Custis finally assented after hearing a “prudent speech” given by Martha.15

Print depicting a young Martha Dandridge, later Martha Washington (after an earlier portrait). Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Daniel and Martha married in 1750, less than a year after Custis’s death. When Daniel died in 1757, a third of the Custis estate passed to Martha, with the rest held in trust for their two children. Martha’s control over the Custis estate made her the most eligible widow in Virginia. She married George Washington in 1759. Together, they managed the Custis estate’s Williamsburg properties until 1778.16

Jack

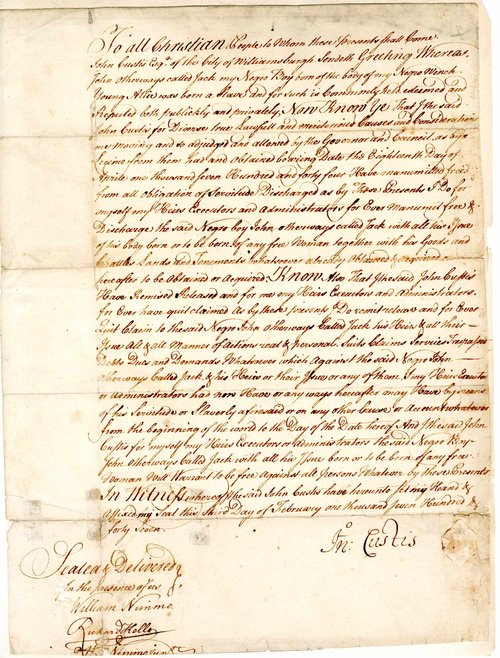

Custis fathered an enslaved Black child named Jack. While this was not uncommon among Virginia planters, Custis was unusually affectionate toward the boy. A deed of manumission for Jack, included with Custis’s will, referred to him as “John otherways called Jack my Negro Boy born of the body of my Negro Wench Young Alice.”17 Little is known of Jack’s mother Alice, or the nature of her relationship to Custis.

Manumission papers for Jack, drawn up by John Custis IV, dated Feb. 3, 1747. From the original at the Rosenbach Museum & Library (Philadelphia, PA), accession no. AMs 788/12.

While arguing with Daniel about his courtship of Martha Dandridge, one family account, written later, indicates that Custis wrote and recorded a will leaving “all his fortune” to Jack. As Daniel tried to secure his father’s blessing for the marriage, the family lawyer presented Jack with a pony in Daniel’s name, “which was taken as a singular favor.”18

Usually austere with his affections, Custis wrote more sentimentally about Jack. In a letter written to Daniel in the last years of his life, Custis noted that “my dear black boy” Jack was sick. If Jack died, Custis commented, “It would break my heart, and bring my grey hairs with sorrow to the grave my lif[e] being wrapt up in his.”19 Custis’s will required that when Jack reached the age of twenty, he would be given land in York County, a nicely furnished “handsome strong convenient dwelling house,” and three horses.20 The will also mentioned a portrait of Jack, which has never been located.21 Unfortunately, Jack died before he could benefit from these bequests.22

Williamsburg

Custis moved to Williamsburg sometime around 1714 to 1717, about the time that his wife died.23 His home, built on a large four-acre lot south of Palace Green, was one of the most impressive in town. He once boasted that he had “as strong and as high a house as any in the Government.”24 Custis likely purchased land north of his home to protect its line of sight with Bruton Parish Church, ensuring that Williamsburg’s residents would see his house every week as they walked out of Sunday services.

Moving to the colonial capital brought him into closer contact with Virginia’s leaders, including his neighbor Lieutenant Governor Alexander Spotswood. The two men were initially friendly. Spotswood was a godfather to Custis’s son Daniel. But their relationship quickly soured. Around 1717, Spotswood received permission from Custis to clear some firewood from lands Custis owned near the Williamsburg Governor’s Palace, hoping to create a striking vista for the new building. But Spotswood’s workmen, according to Custis, “cut down all” the trees at “such a wideness as he thought fitt.” Custis sent his complaints to Spotswood and soon heard that the lieutenant governor was saying “all the little mean things of me.”25

Another dispute, over the leadership of Bruton Parish Church, widened the gulf between the men. Despite their close proximity, Custis once reported to Byrd that he had not spoken to Spotswood in nearly a year.26 Custis and other leading Virginia planters complained about Spotswood to London officials. He was eventually replaced. The new governor Hugh Drysdale appointed Custis to the colony’s powerful Council, confirming his status as one of the colony’s leading men.27

Home and Garden

Custis had an impressive Williamsburg home. Though the home was modestly sized, it was furnished to convey his status and power. It was filled with prints and paintings. It had a large library. His correspondence records his efforts to secure fine furnishings, like a “good and handsom” bed and an attractive painted fire screen to cover the fireplace during summer.28

The Gardens of Colonial Williamsburg

Williamsburg was one of the centers of ornamental gardening in colonial America.

Shortly after moving to Williamsburg, he took up gardening.29 Over several decades of cultivation, he created a garden that he claimed was “inferior to few, if any, in Virg[ini]a.”30 It featured topiaries, espaliered fruit trees, gravel walks, classical statues, and more, cultivated by enslaved gardeners. He corresponded with naturalists abroad and experimented with exotic plants to build his garden. Yet his aims were often frustrated by Virginia’s harsh climate. By 1730, he wrote that he was “out of heart of endeavoring any thing but w[ha]t is hardy and Virginia proof.”31

Illness and Death

Custis complained regularly about illness. In 1741, he experienced a particularly difficult period of health. Fearing that he would “bee a cripple all the days of my life,” he noted that he “often wishd for death.” He turned in his final years to his garden and to his books: “at present I have little taste for anything[.] my garden is the chiefest pleasure I have besides reading which if I did not delight in should have run mad.”32 Despite his many health problems, Custis died in 1749 at the age of 71.

The tomb of John Custis IV. The inscription has mostly been eroded away over the centuries. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Like many Virginia plantation owners, Custis had sought control over his world: the people in his family, the hundreds of people he enslaved, the colonial government, and even the land itself. Yet he found, like many of his contemporaries, that his will was not obeyed. His wife and children defied him. Enslaved people resisted and escaped. Governors challenged him. Even his garden withered in the summer heat. John Custis IV may have been a man of great status and wealth, but the epitaph on his tombstone testifies that he died a deeply dissatisfied man.

Sources

Cover image: Courtesy of Museums at Washington and Lee University, Lexington, Virginia.

- Quoted Jo Zuppan, “John Custis of Williamsburg, 1678–1749,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 90 (April 1982): 195–96.

- Zuppan, “John Custis of Williamsburg,” 178–79.

- William Byrd II, The Secret Diary of William Byrd of Westover, 1709–1712, eds. Louis B. Wright and Marion Tinling (Dietz Press, 1941), 29.

- Byrd, Secret Diary of William Byrd, 312, 517; Zuppan, “John Custis of Williamsburg,” 189.

- Byrd, Secret Diary of William Byrd, 507.

- “A Marriage Agreement,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 4, no. 1 (July 1896), 64–66.

- Quoted in Zuppan, “John Custis of Williamsburg,” 183.

- Scattered references to enslaved people in his correspondence include a 1738 description of his directions to three “strong” enslaved men to fill “large tubs of water” and shade his garden’s plants to protect them during a drought. A few years later, he commented that he “dayly assist[ed]” the enslaved people “in my several familys” when they were ill. E. G. Swem, ed., Brothers of the Spade: Correspondence of Peter Collinson of London, and of John Custis, of Williamsburg, Virginia. 1734–1746 (Barre, Mass.: Barre Gazette, 1957), 55, link, 78, link.

- “A Marriage Agreement,” 66.

- “An act for suppressing outlying Slaves,” in The Statutes at Large: Being a Collection of All the Laws of Virginia, from the First Session of the Legislature, in the Year 1619, ed. William Waller Hening (Philadelphia: Thomas Desilver, 1823), 3:86.

- Quoted in Zuppan, “John Custis of Williamsburg,” 188.

- Zuppan, “John Custis of Williamsburg,” 191.

- “Virginia Gleanings in England,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography vol. 15 (Jan. 1908): 302–3, link.

- Zuppan, “John Custis of Williamsburg,” 194.

- Jo Zuppan, ed., “Father to Son: Letters from John Custis IV to Daniel Parke Custis,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 98 (Jan. 1990): 86; See footnote 5, “To George Washington from James Hill, 11 May 1773,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-09-02-0171.

- “From George Washington to John Parke Custis, 12 October 1778,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-17-02-0373.

- Zuppan, ed., “Father to Son,” 100.

- Recollection and Private Memoirs of Washington, By His Adopted Son, George Washington Parke Custis (Derby & Jackson, 1860), 20, link.

- Zuppan, ed., “Father to Son,” 99.

- Zuppan, ed., “Father to Son,” 88n24.

- Zuppan, “John Custis of Williamsburg,” 196.

- William and Mary College Quarterly Historical Magazine, vol. 7 (Richmond: Whittet & Shepperson, 1899), 152, link.

- On Custis’s property, see Mary A. Stephenson, “Custis Square Historical Report, Block 4 Lot 1-8” (1959), Colonial Williamsburg Digital Collections.

- Josephine Little Zuppan, ed., Letterbook of John Custis IV of Williamsburg 1717-1742 (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2005), 65.

- John Custis to Phillip Ludwell II, April 18, 1717, in Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 46 (July 1938), 244–45.

- Zuppan, “John Custis of Williamsburg,” 184.

- Anthony S. Parent Jr., Foul Means: The Formation of a Slave Society in Virginia, 1660–1740 (Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, 2003), 186, 191.

- Zuppan, “John Custis of Williamsburg,” 190–91.

- Zuppan, ed., Letterbook of John Custis IV, 35.

- Swem, ed., Brothers of the Spade, 23–24.

- Zuppan, ed., Letterbook of John Custis, 109.

- Custis to Peter Collinson, [April 20, 1741], in Swem, ed., Brothers of the Spade, 72–73, link.