While an all-male Advisory Committee of Architects periodically visited Williamsburg to critique the progress of architectural restoration work in the 1930s, a group of female counterparts also played a role in guiding the decision-making process, particularly regarding interior décor and furnishings.

Stories of Women

Women played important and, at times, unexpected roles in early Williamsburg. Their stories, often hidden in the historical record, illuminate their rich contributions to eighteenth-century Virginia's social, economic, and political life. Join us as we celebrate and examine the experiences, lives, and relationships of these women.

The Population of Williamsburg in 1775

Williamsburg women’s experiences differed radically based on their race, class, and legal status. Women like Clementina Rind took over the family business after the death of a husband. Gentry women managed their households, including the enslaved men, women, and children whose labor including household cleaning, cooking, laundry, and more. Enslaved women’s skilled labor, like Lydia Broadnax’s cooking, supported elite households and enabled their enslavers to engage in politics, philosophy, and other intellectual pursuits.

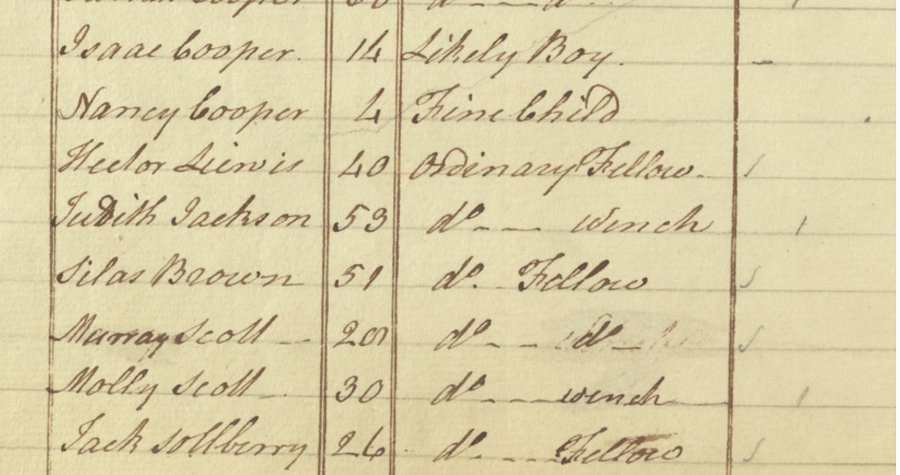

The American Revolution drastically changed these women’s lives. Milliner Margaret Hunter navigated her business through economic uncertainty. When the British offered freedom to enslaved people who self-emancipated and join them, Judith Jackson was one of thousands who risked everything for her freedom. Women navigated the chaos of revolution by managing businesses and households, boycotting British goods, supporting the military, protecting their families and properties, running to freedom, spying on their enemies, and much more.

How do we know about these women? Researchers scour the diaries, letters, and published narratives written by women in the eighteenth-century women for clues about their attitudes, experiences, and feelings. They assess men’s own accounts of their interactions with wives, daughters, love interests, and acquaintances. They delve into newspapers, court records, business records, account books, runaway advertisements, archaeology, and artifacts to understand women’s lives. They conduct and consult oral histories to better understand elements of the past that were not written down. They put together puzzle pieces from the past to reconstruct the lives of the eighteenth-century women, revealing their contributions to a changing world.

Stories of Strength

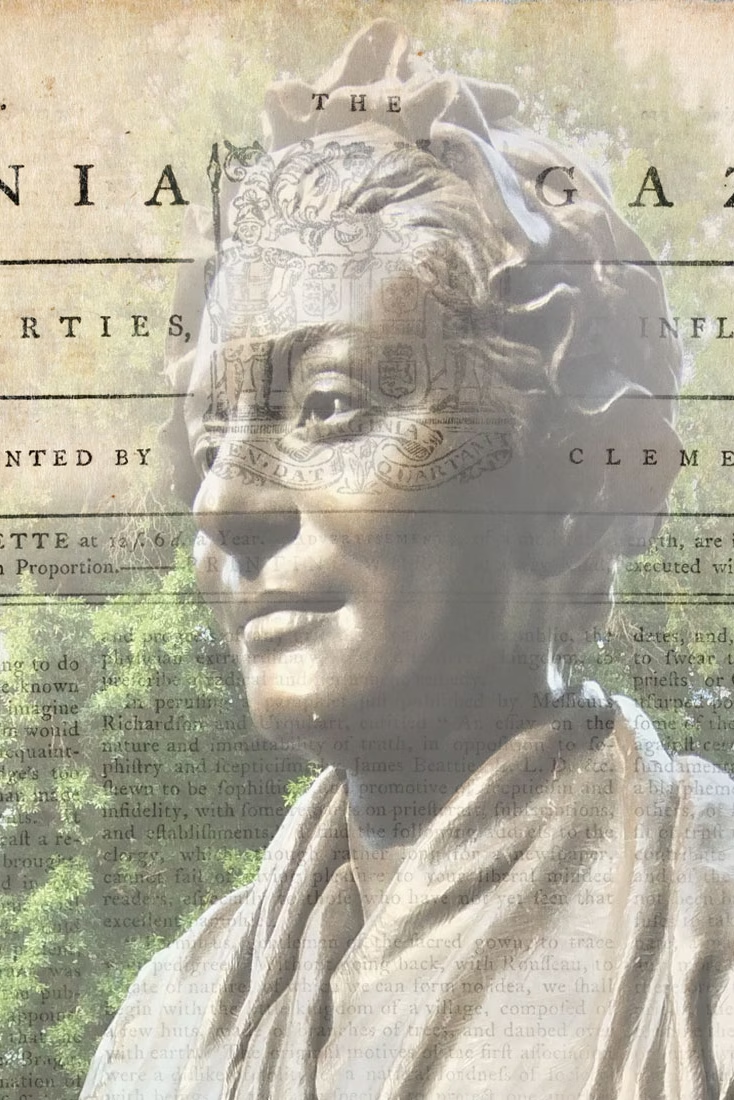

Lydia Broadnax

Unheard Witness to the murder of George Wythe

Abigail Briggs

An Indigenous Woman in a White Court

Judith Jackson

A Black Loyalist Flees Virginia

FAQs about Women in Colonial Virginia

Meet Our Nation Builders

Ann Wager

Educator at the Bray School in Williamsburg

Jane Vobe

Successful Williamsburg tavernkeeper

Martha Washington

The First First Lady

Watch & Learn More

Women & The Revolution

Women of the American Revolution

The American Revolution transformed women’s lives. Women’s choices, including what they bought and who they married, carried new political weight. For enslaved women, the upheaval created new opportunities for freedom.

How Enslaved Women in Revolutionary Virginia Escaped to Freedom

Enslaved women navigated extraordinarily difficult and often perilous choices during the Revolution. While historical records sometimes document the decisions they made, they rarely capture the personal motivations, emotions, or consequences of these choices. They rarely tell us what it meant to leave or to be left behind.

Women & The Restoration

Lena Richard was a woman who began as a domestic cook and ended up a nationally known chef with a frozen foods line, a cookbook, a television show, and diners willing to cross the segregation line to eat at her establishments. She was a pioneer who achieved an astonishing amount and though she brought her culinary magic to Colonial Williamsburg for but a brief time, all Travis House diners departed dreaming of her Creole cooking.

Long an avid gardener, Louise Bang Fisher became involved with flower arranging for Colonial Williamsburg when she became a hostess at the Raleigh Tavern, the first exhibition building that opened in 1932. Fisher began providing flower arrangements for the Raleigh in an effort to provide a homier feel for visitors and she soon expanded her efforts to other exhibition buildings.

Additional Resources

Learn even more about women by exploring these resources from both our museum and other trusted institutions.