Governor’s Palace Gardens

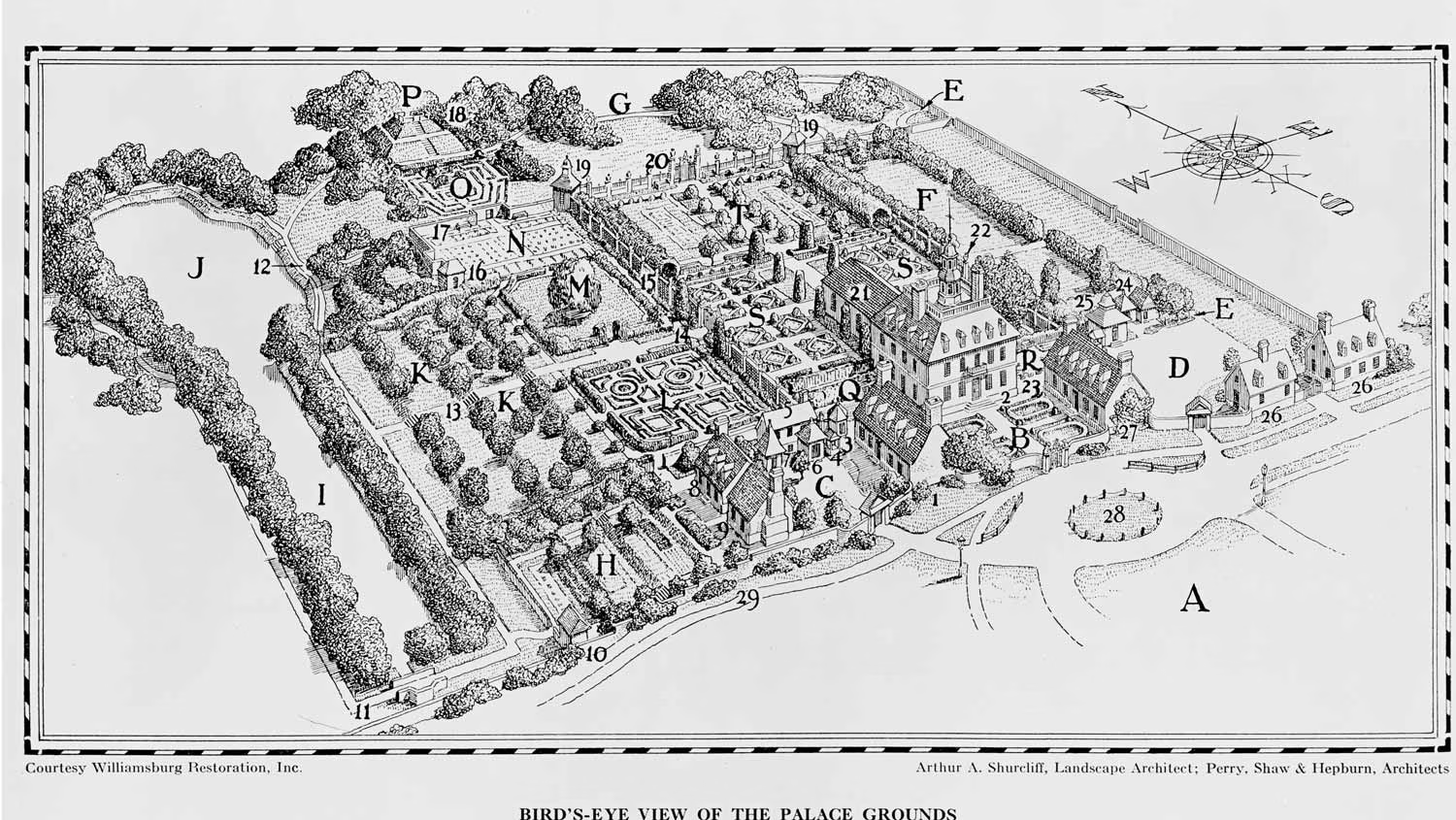

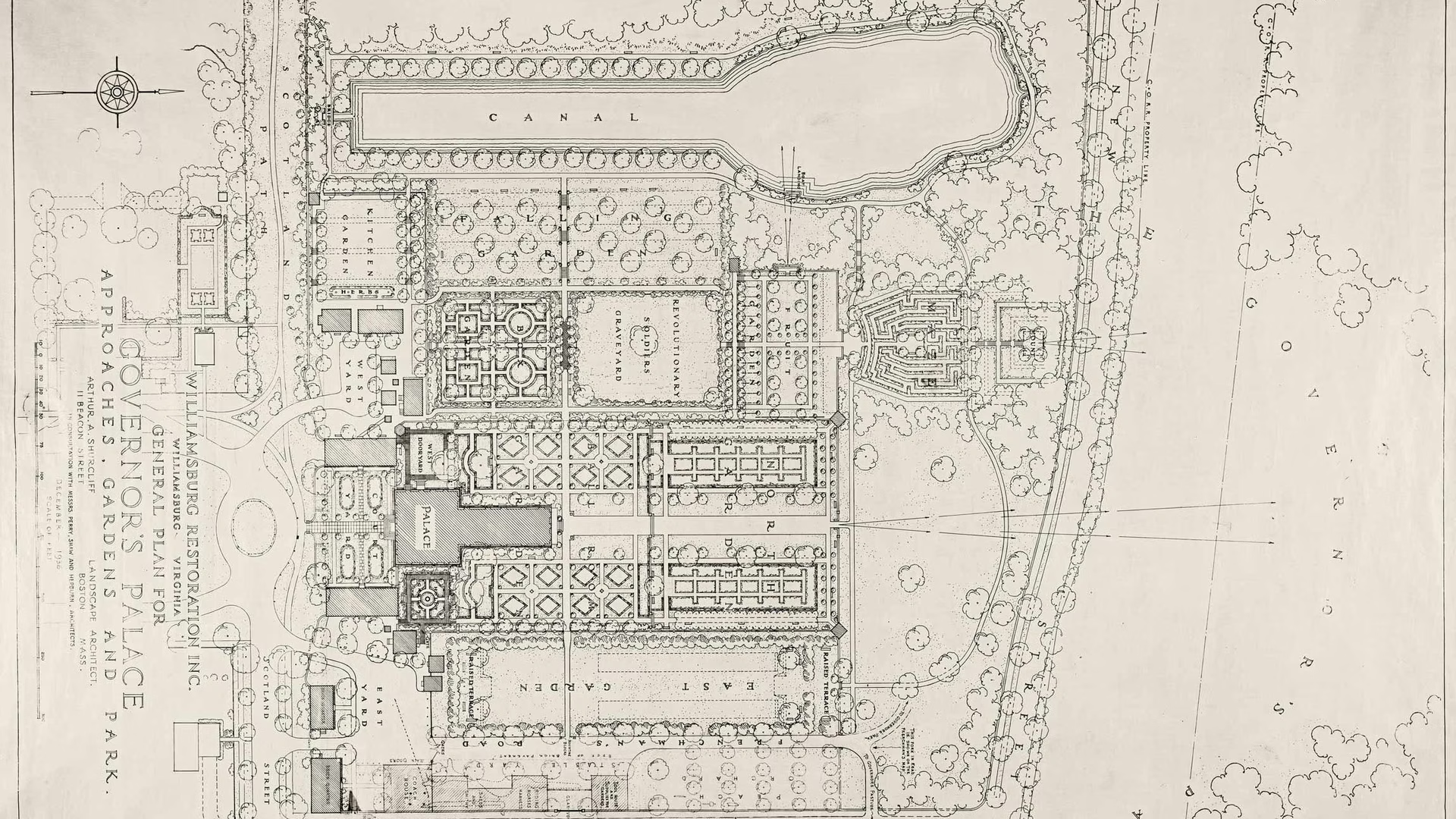

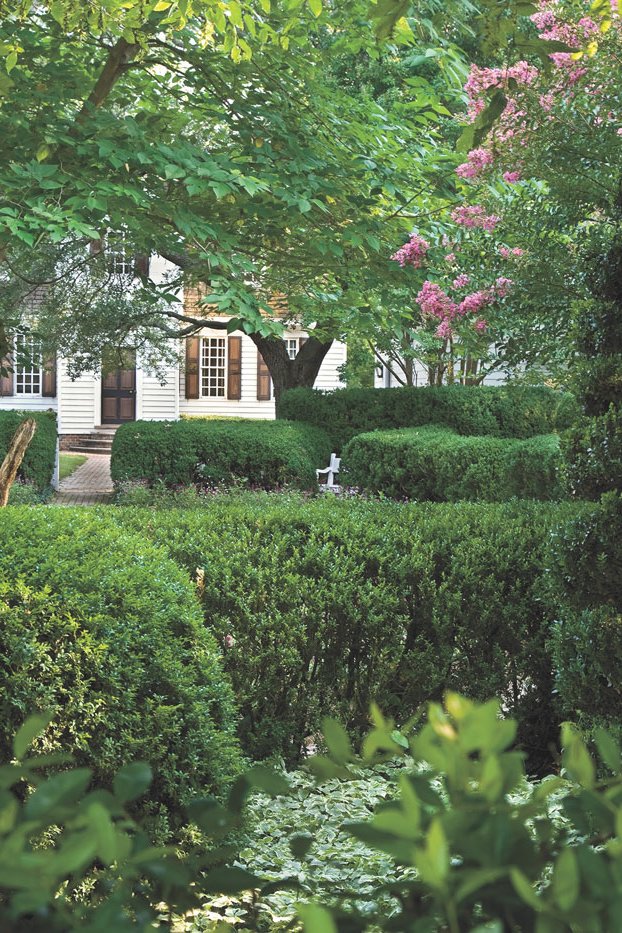

The Palace grounds, including its gardens and evergreen maze, are a beautiful place to spend an afternoon. But they are also an important historic site. Tended by servants and enslaved people, the carefully manicured gardens of the Governor’s Palace displayed Virginia’s growing power and prestige. Today’s ten-acre complex of gardens reflects the garden style during the reign of the British monarchs William and Mary. Several eighteenth-century features have been restored, including the terraces, the canal, and the ice mount.

Spotswood’s Moneypit

Elegant gardens were an important feature of any grand eighteenth-century home.1 When Virginia’s assembly planned to build a home for their governor, they provided funds to create an ornamental garden, a courtyard, walls, “handsome gates,” an orchard, and a kitchen garden.2 But construction stalled. When Lieutenant Governor Alexander Spotswood arrived in 1710, he took over as landscape architect. The next year, he wrote to his brother that he was “amused with planting Orchard & Gardens” and finishing the Palace “at the Country’s Charge.”3

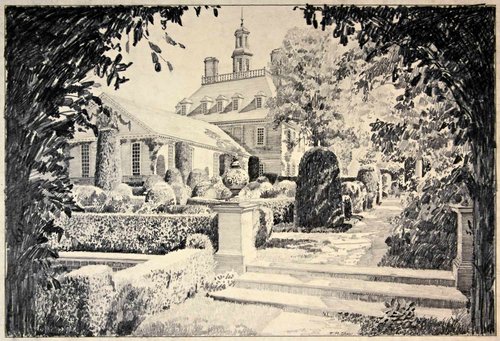

Palace Ballroom Wing Viewed from Pleached Arbor, Thomas Mott Shaw, late 1930s. Special Collections, John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library.

After several years of slow progress, Virginia’s elite got tired of paying for Spotswood’s landscaping. In 1718, the House of Burgesses asked him if the house and gardens were complete, and if not, how much more money was required? He responded tersely: “It is not finisht and I don't know how much it will take.”4 A few months later, the Burgesses sent a letter to London charging that Spotswood, among other things, “lavishes away the Country’s money” in finishing the Palace and its gardens.5

Spotswood snapped back. He had saved the colony money, he asserted, by serving as the Palace’s landscape architect. He threatened to sell the land if the Burgesses wouldn’t pay for his improvements. When the Burgesses instructed him to walk around the garden and “compute the Charge of the whole,” he lost patience. He told them to find someone else to supervise the garden construction.6 This was one of many sources of conflict between Spotswood and local leaders. Just as the Palace and its gardens were completed, British leaders relieved Spotswood of his duties as Lieutenant Governor in 1722.

Governor's Palace

The Governor’s Palace was home to seven royal governors, Virginia’s first two elected governors, and hundreds of servants and enslaved people. It was built to display the colony’s wealth, power, and permanence.

Gardeners

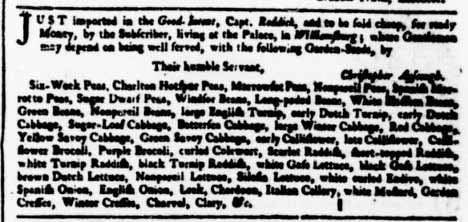

The Palace usually employed a white gardener who supervised enslaved assistants. Gardener Thomas Crease worked at the Palace as well as the College of William & Mary and possibly on wealthy plantation owner John Custis IV’s magnificent garden. His successor was Christopher Ayscough, who ran a side business out of the Palace selling seeds. Later gardeners included James Simpson (whom Governor Botetourt brought from England), James Wilson, and John Farquharson (or Ferguson).7

In 1759, gardener Christopher Ayscough advertised seeds for sale at the Palace. Virginia Gazette, Nov. 30, 1759, p. 3.

But most of the people who planted and maintained the Palace gardens were enslaved. An enslaved man named Lancaster worked alongside Ayscough. When Governor Francis Fauquier died in 1768, his will allowed Lancaster and others to choose their next enslaver. Lancaster chose Ayscough as his purchaser, but he was later offered for sale again when Ayscough’s next business failed.8 Another enslaved man named James worked under three different governors at the Palace from 1765 to 1777. James’s enslaver Lewis Burwell lent him to the Palace for £12 per year—a relatively high payment. Given this cost and his longevity at the Palace, it is likely that James was a highly skilled gardener.9

What Did the Gardens Look Like?

Gardens are living things. While the Palace gardens likely evolved over time in response to changing fashions and needs, we know that its ornamental features included geometric flower gardens (parterres), terraced gardens (“falling” gardens) carved from a ravine, a canal, a fish pond, and an earthen mount covering an ice house. These features were widely admired and imitated in Virginia.10

Spotswood designed the landscape to create stunning views. The geometric designs of the gardens could be enjoyed from the building’s upstairs windows or the mount. Instead of a fence, which would ruin the view from the Palace, a large ditch called a “ha-ha” kept livestock out.11 To complete his vision, Spotswood received John Custis IV’s permission to cut down some trees in front of the building (likely on what is now the Palace Green). According to a letter written in 1717, Custis agreed to Spotswood’s plan to “make an opening, I think he called it a vista,” but believed only a few trees would be cut. He was furious when Spotswood subsequently “cut down all before him.” Afterward, perhaps in part because of this dispute, Custis became an avowed enemy of Spotswood, and helped to have him removed from office.12

Colonial Gentry Gardening

How did wealthy Virginians, like the governors, use plants to display their wealth, education, and knowledge? Like other large, ornamental gardens, the Palace Gardens were built to impress.

Though designed to be beautiful, the Palace’s grounds were also functional. The kitchen garden produced vegetables and herbs. The orchard supplied apples, pears, plums, nectarines, peaches, and other fruits. The fishponds were stocked with fish that would end up on the governor’s table. In these ways, the Palace grounds helped to feed Williamsburg’s largest household.13

Restoring the Palace Gardens

In the 1930s, the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation began to restore the Palace gardens. The landscape architect Arthur Shurcliff planned the restoration, based on archaeological discoveries, documentary evidence, and examples of contemporary garden style in England and North America.

Learn More

Garden Getaway

These mainstays are part of the Historic Area’s garden geometry — and it’s a beautiful lesson

Home Grown

The historic gardener answers your cultivation questions

Gardening by Moonlight

Enslaved Peoples’ Plantation Gardens in Virginia

Arboretum & Gardens

More than 30 carefully maintained gardens dot our 301-acre living history museum. From flowering backyard pleasure gardens to our grand Governor’s Palace Gardens and Grounds, these gardens can offer insight into how the colonists lived and worked as a community.

Sources

- Richard Bushman, The Refinement of America: Persons, Houses, Cities (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1992), ch. 4.

- William Waller Hening, ed., The statutes at large; being a collection of all the laws of Virginia, from the first session of the legislature, in the year 1619 (Philadelphia: Thomas Desilver, 1823), 3:482–86, link.

- Alexander Spotswood to John Spotswood, March 20, 1711, in Lester J. Cappon, ed., “Correspondence of Alexander Spotswood with John Spotswood of Edinburgh,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 60 (April 1952): 229.

- H. R. McIlwaine, ed., Journals of the House of Burgesses of Virginia, 1712–1714, 1715, 1718, 1720–1722, 1723–1726 (Richmond: Colonial Press, 1912), 205, link.

- McIlwaine, ed., Journals of the House of Burgesses of Virginia, 230, link.

- Peter Martin, The Pleasure Gardens of Virginia: From Jamestown to Jefferson (Charlotte: University Press of Virginia, 2001), 53.

- Graham Hood, The Governor’s Palace in Williamsburg: A Cultural Study (Williamsburg: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1991), 250; Peter E. Martin, “The Governor’s Palace Gardens: ‘lavishing away’ The Colony’s Money,” Colonial Williamsburg Digital Library, 24–32

- On Lancaster, see “The Governor’s Palace Historical Notes,” Colonial Williamsburg Digital Collections, p. 90; Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon), Sept. 20, 1770, p. 3, link.

- Martin, “The Governor’s Palace Gardens,” 28.

- On the impact of the Palace gardens on other Virginia gardens, see Robert P. McCubbin and Peter Martin, eds., British and American Gardens in the Eighteenth Century: Eighteen Illustrated Essays on Garden History (Williamsburg: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1984), 96, 114, 163.

- James D. Kornwolf, “The Picturesque in the American Garden and Landscape before 1800,” in McCubbin and Martin, eds., British and American Gardens in the Eighteenth Century, 96.

- Mary E. McWilliams and Helen Bullock, “Custis Tenement Historical Report, Block 13-1 Building 26A Lot 355,” Colonial Williamsburg Digital Collections, p. 1. See discussion of this conflict in Martin, “‘Promised Fruites of Well Ordered Towns,’” 319–20.

- Peter Martin, “‘Promised Fruites of Well Ordered Towns’—Gardens in Early 18th-Century Williamsburg,” Journal of Garden History 2 (no. 4, 1982): 318.

- M. Kent Brinkley and Gordon W. Chappell, The Gardens of Colonial Williamsburg (Williamsburg: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1996), 86.

- Brinkley and Chappell, Gardens of Colonial Williamsburg, 82.