The Alternative of Williams-Burg

On November 10, 1774, The Virginia Gazette reported that merchants assembled in Williamsburg the previous day and “voluntarily and generally” agreed to stop importing British goods.1 Readers might have believed this story. But it was wrong.

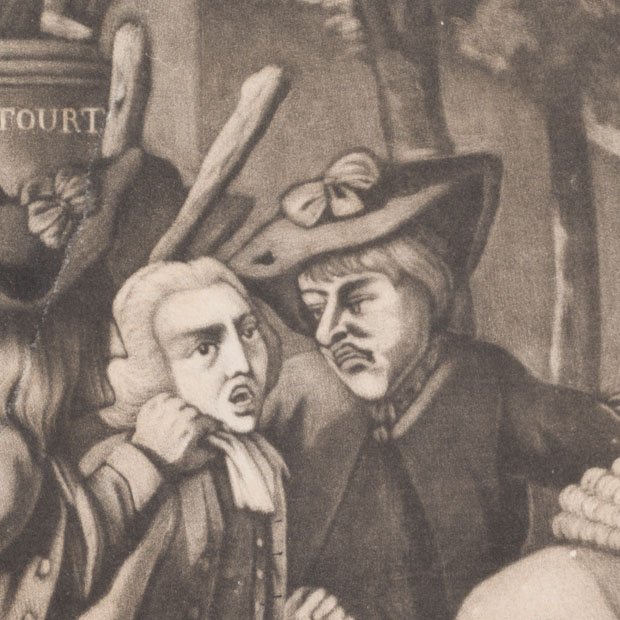

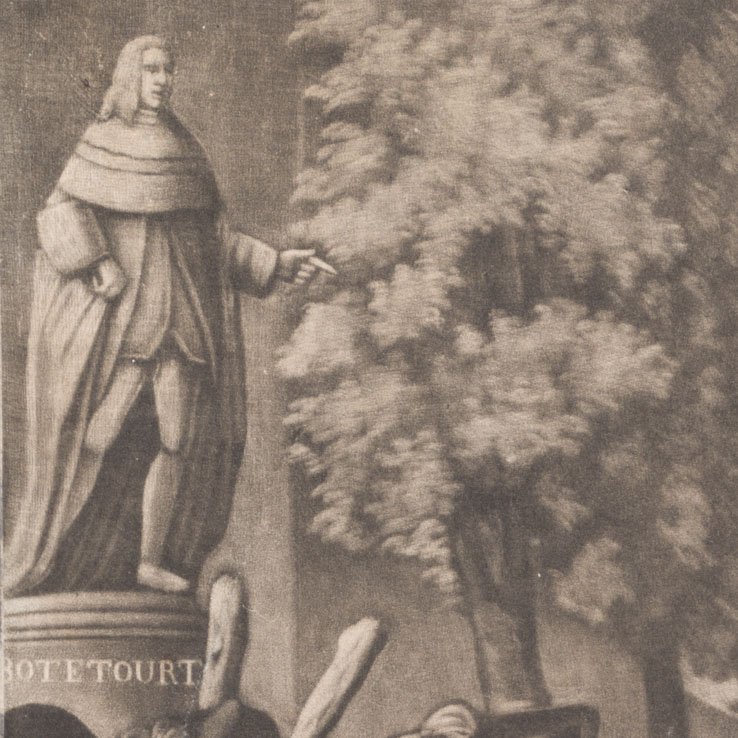

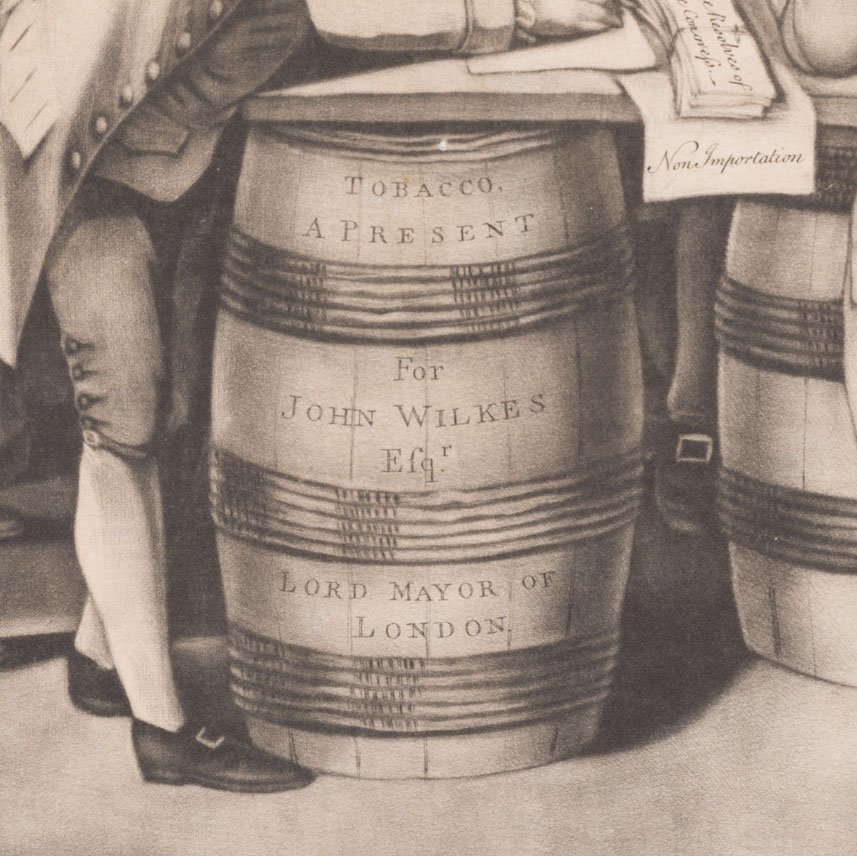

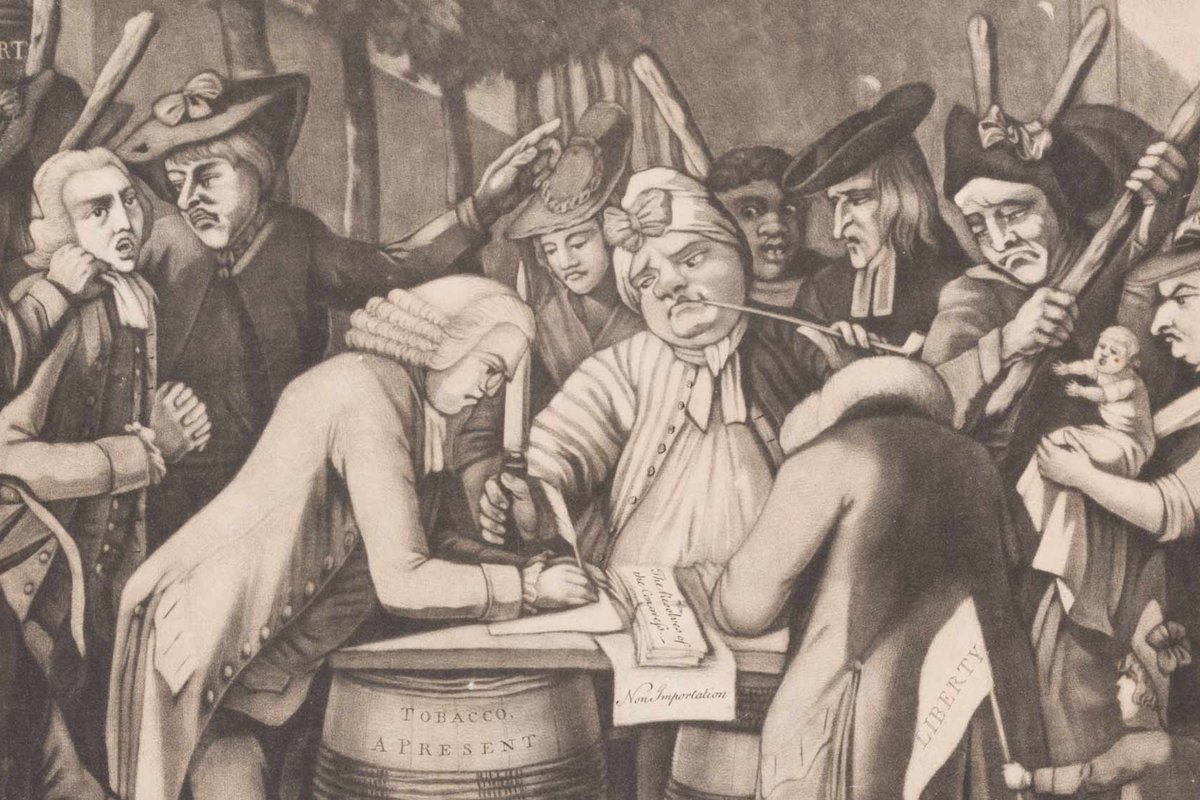

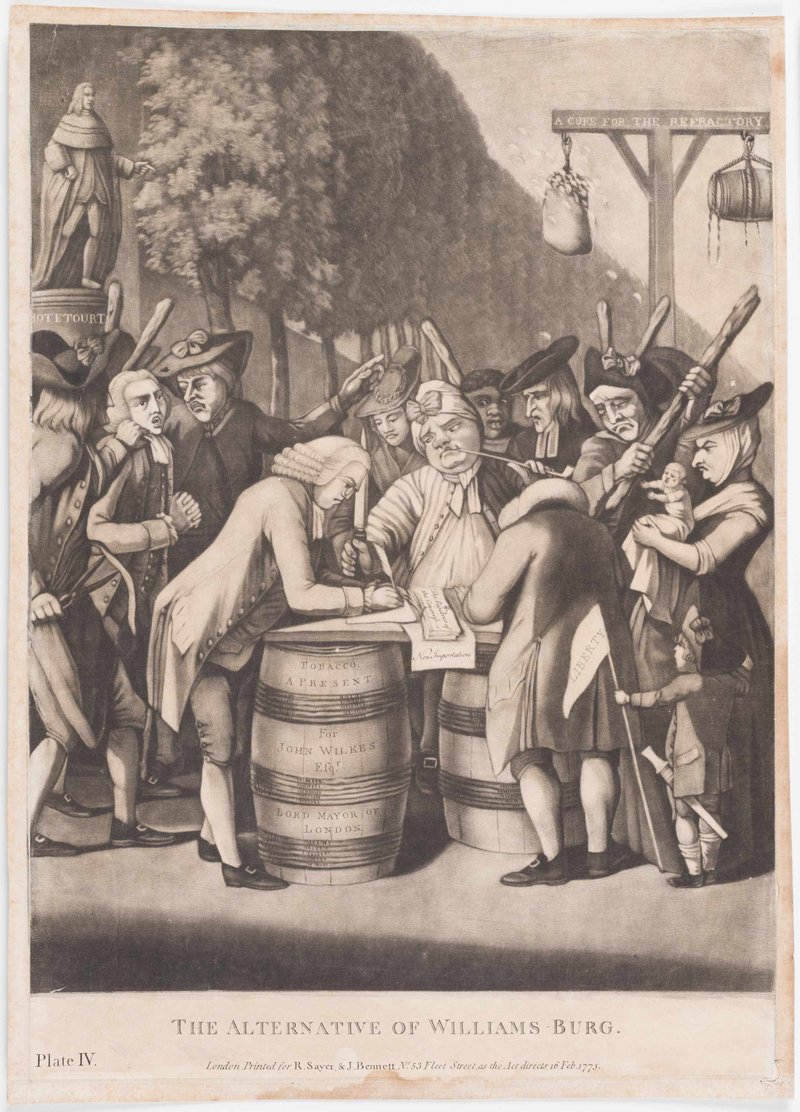

By February, an alternative account of the events of November 9 emerged. This satirical print, created in London, portrayed the same event. But it did not look like a voluntary agreement. The print showed merchants being intimidated into signing the boycott, with tar and feathers hanging as a threat in the background.2 Ironically, the London account more closely represented what actually happened in Williamsburg on November 9. So how did a version of events from over 3,000 miles away and three months later end up being more accurate than one published locally the very next day?

Philip Dawe (attributed), The Alternative of Williams-Burg, February 15, 1775. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1930-607

The Virginia Gazette's Account

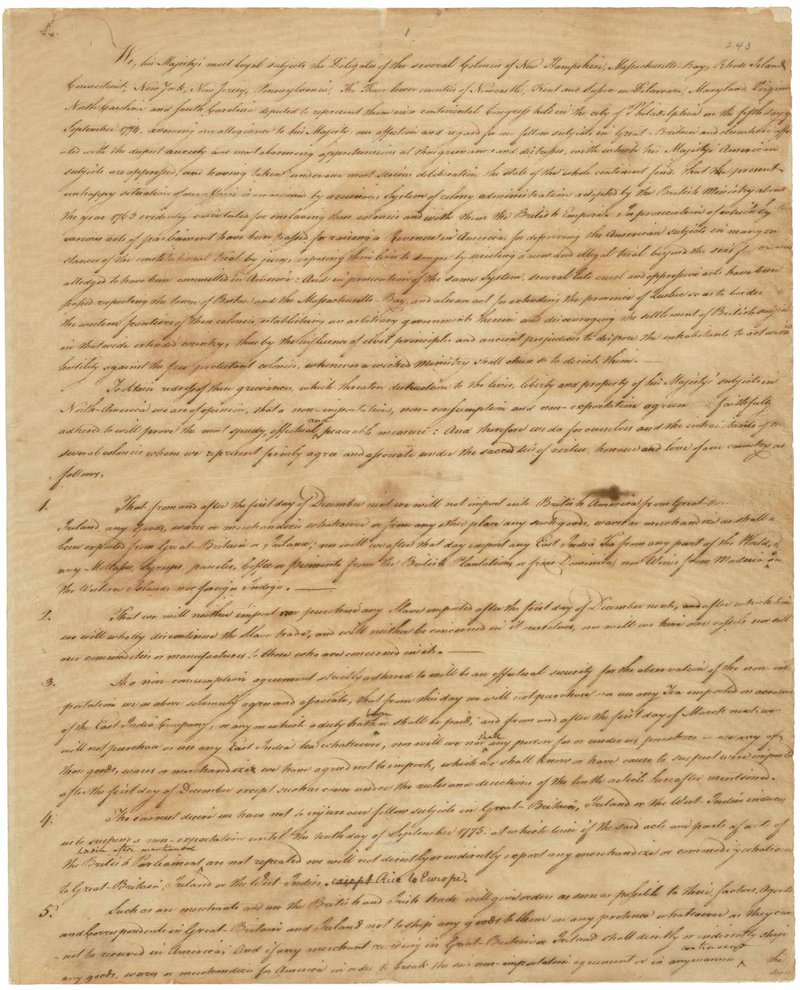

The meeting reported in the Virginia Gazette did really happen. On November 9, 1774, merchants from across the colony of Virginia gathered in Williamsburg. One goal of the meeting was to discuss and sign The Continental Association, a boycott of British goods that would officially begin on December 1.3

Continental Congress, Articles of Association, October 20, 1774. National Archives Foundation.

The boycott’s proponents hoped it would put enough economic pressure on British merchants that they would plead the colonists’ case to Parliament. To be effective, the boycott needed near-universal support.4 How could Patriots convince neutral or Loyalist merchants to adhere to a cause they didn’t support?

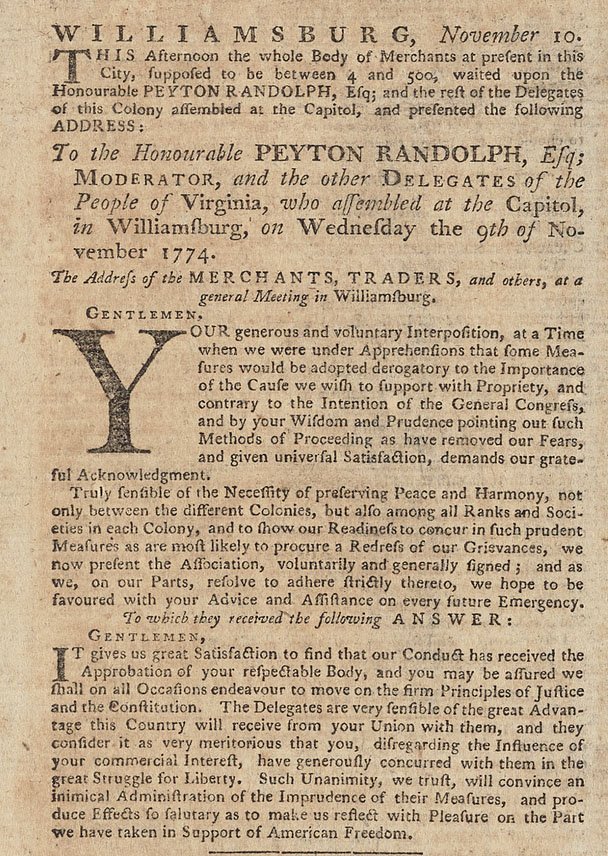

The locally printed newspaper did not admit that there were any dissenters. The Virginia Gazette did not report directly on the November 9 meeting. Instead, it shared details from a meeting held the next day between the merchants and Virginia legislators. At that meeting, merchants told legislators that they had “voluntarily and generally” signed the boycott, and everyone believed this was a necessary sacrifice “in the struggle for Liberty.”5

Virginia Gazette (Purdie & Dixon), November 10, 1774.

Eyewitness Reports Spread

Private letters tell a different story. Norfolk-based merchants James Parker, William Aitchison, and Henry Fleming shared their own versions. Of the three men, only Henry Fleming had been present for the meeting in Williamsburg. Fleming shared his account with others, who shared with others, and so on. Word spread not through official news sources, but through conversations in parlors and taverns.6 Then they committed these accounts to paper in letters that carried the news across an ocean. Their accounts paint a radically different picture of that day compared to the version published in the Virginia Gazette.

Liberty Pole recreated at Colonial Williamsburg in 2015.

Conflict arose at the meeting because two merchants, Anthony Warwick and Michael Wallace, had recently imported tea from Great Britain. A mob forced them to sign the Association and agree not to sell the tea. Henry Fleming wrote that “There was a pole erected upon the parade in Wmsburg when I was there with a Brush a Bag of feathers & a Tar Barrel at its foot.” The threat was real. Fleming went on to say, “Hanging Drowning Ducking Taring & Feathering, Beating to death & Gouging was threatened & recommended in my hearing.”7 Several more cool-headed men, including the Peyton Randolph, Speaker of the House of Burgesses, helped to negotiate on Warwick and Wallace’s behalf, arguing “that such proceedings was more arbitrary than any the Americans were complaining of.”8 In the end, the mob did not tar and feather the two merchants, and the two men agreed to turn the tea over to be burned.9

In short, the times are really shocking.

— Henry Fleming

The events of November 9 had a lasting impact on the people who witnessed the mob, and how they viewed the American Revolution. Fleming did not mince words, telling his business partners that, “In short whilst some are contending for Liberty they are willing to deprive others of every pretention to it from which I conclude every one here is a Tyrant as far as his power extends.” “In short,” he said, “the times are really shocking.”

So why didn’t the Virginia Gazette report this version of events? According to Parker, the Patriots "Scared the printer so that he will only write what is agreeable to them.”10

Because Virginia’s printers chose to print news that catered to their Patriot audiences, it was word of mouth and private letters that communicated the full story of what happened.

A Glasgow Newspaper’s Report

These letters conveyed news of the event from Virginia to Britain, where a London newspaper reported briefly on what happened. The newspaper reported that in Williamsburg, “They erected, at the end of the principal avenue to the town, a very high gibbet; upon the one side of which they hung a barrel of tar, and on the other side a bag of feathers; and on each of them the following inscription: A cure for the refractory.”11 No extant letters mention an inscription on the gibbet, tar, or feathers. Was this a fabricated detail, or did the article’s author have an additional source? We might never know. What we do know is that this stray, possibly made-up, detail made its way into a drawing of the event printed in London one month later.

Prints in the Eighteenth Century

Prints spread political ideas in the eighteenth century, but that was just one of the many ways people used prints in their everyday lives.

The Alternative of Williams-Burg

In The Alternative of Williams-Burg, London print-publishers Robert Sayer and John Bennett gave shape to an event they had not witnessed, on a continent they had never visited. By visually representing the events of November 9, they made it into something that could easily be spread, shared, and understood. The print itself is made after a watercolor by Samuel Hieronymus Grimm.12 By making an engraved version of the watercolor, the image could be printed and shared.

The watercolor and print are satires that were aimed at making the viewer laugh more than pushing a political agenda.13 The print itself portrays a mob intimidating merchants into signing the Association. Through symbols and other visual elements that well-informed British subjects would have understood in the eighteenth century, the print makes fun of colonial Patriots and makes their cause laughable.

But as satire often does, it also pointed out hard truths. A mob of Patriots who demanded liberty had forced people to go along with them, depriving them of their liberty. While the Patriots had kept this from the local newspaper, they couldn't keep it out of London’s prints.14

Minding the Gaps in Evidence about Revolutionary America

Patriots knew the impact of the press, and they used it to their advantage. They routinely suppressed dissenting views while promoting their own version of events.15 What other events spread through word of mouth but were never written down? What events were written about on paper that was later discarded? By tracing how the news about November 9 spread, we can see how lucky we are to have surviving sources about this potential tarring and feathering. And we also find how much we don’t know about political dissent and violence in revolutionary Virginia.

Sources

- Virginia Gazette (Purdie & Dixon), November 10, 1774, 1, link

- Philip Dawe (attributed), “The Alternative of Williams-Burg,” February 16, 1775, link

- “Continental Association, 20 October 1774,” Founders Online, link; James R. Fichter, “Collecting Debts: Virginia Merchants, the Continental Association, and the Meetings of November 1774,” Virginia Magazine of History & Biography 130, no. 3 (2022): 173–75.

- Fichter, “Collecting Debts,” 182. For more on the non-importation movement, see T. H. Breen, The Marketplace of Revolution: How Consumer Politics Shaped American Independence (Oxford University Press, 2004).

- Virginia Gazette (Purdie & Dixon), November 10, 1774, 1, link

- On the spread of news in the revolutionary era, see Richard Brown, Knowledge is Power: The Diffusion of Information in Early America, 1730–1865 (Oxford University Press, 1989).

- Henry Fleming to Fisher & Bragg, November 17, 1774, Papers of Henry Fleming, 1772-1795, microfilm, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- James Parker to Charles Steuart, November 27, 1774, Charles Steuart Papers, microfilm, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- William Aitchison to James Parker, November 14, 1774, Parker Family Papers, microfilm, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- James Parker to Charles Steuart, December 6, 1774, Charles Steuart Papers, microfilm, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- Middlesex Journal and Evening Advertiser, January 21–24, 1775.

- Emily Katherine Torbert, “Dissolving the Bonds: Robert Sayer and John Bennett, Print Publishers in an Age of Revolution,” (Ph.D. diss., University of Delaware, 2017), 231; Samuel Grimm, Untitled Watercolor, London Picture Archive, link

- Torbert, “Dissolving the Bonds,” 236–37.

- For analysis of the print and its symbolism, see Torbert, “Dissolving the Bonds,” 225-238. Available records do not indicate whether this print, created in London, made its way to Williamsburg during the Revolutionary period. Record books do indicate that merchants ordered prints from Sayer and Bennet in the 1760s. See Torbert, “Dissolving the Bonds,” 308, and Mary Goodwin, “Printing Office and Post Office Historical (LL) Report, Block 18 Building 12B Lot 48,” Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1952, link

- William B. Warner, Protocols of Liberty: Communication, Innovation, and the American Revolution (University of Chicago Press, 2013).