Prints

"A South East View of the Great Town of Boston in New England in America," 1764. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

Before camera phones and social media, how could a one-of-a-kind painting be seen by thousands of people spread across continents? Prior to the invention of the printing press, sharing art widely was virtually impossible. But just as the printing press allowed for the written word to be shared more easily, the technology of printmaking, developed in around 1400, transformed the accessibility of visual art.

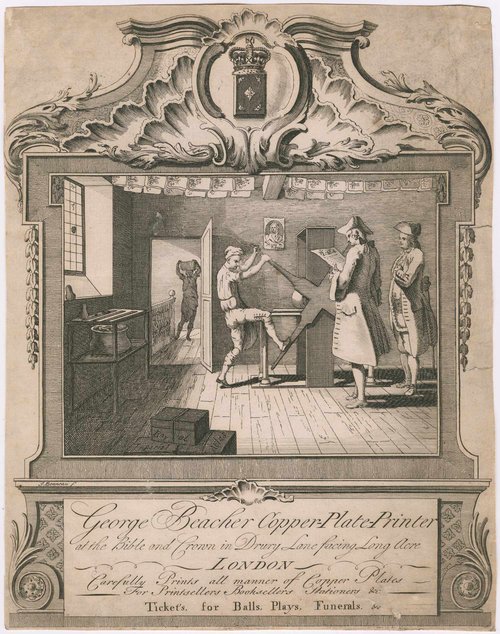

George Beacher Trade Card, ca. 1740. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

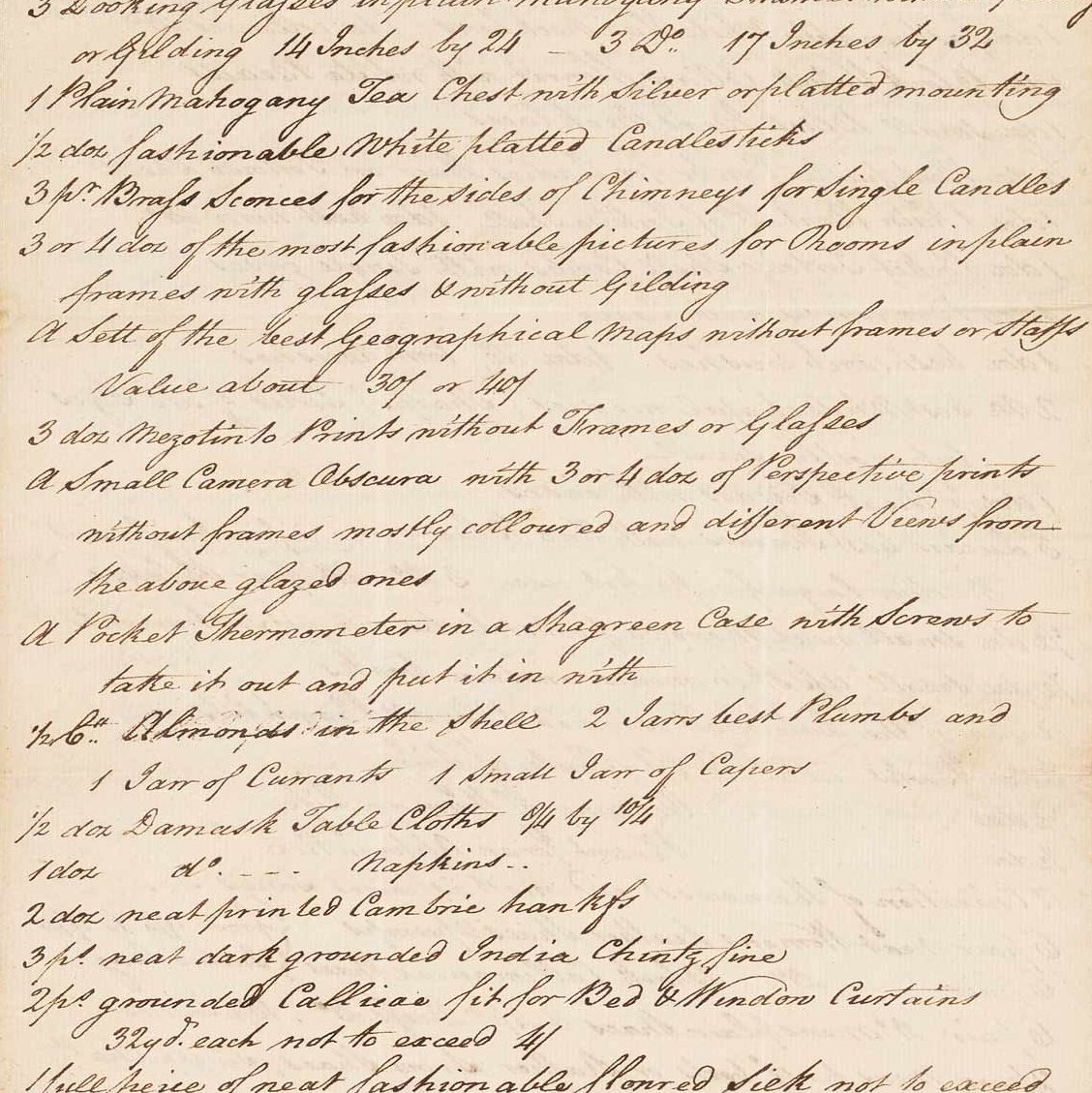

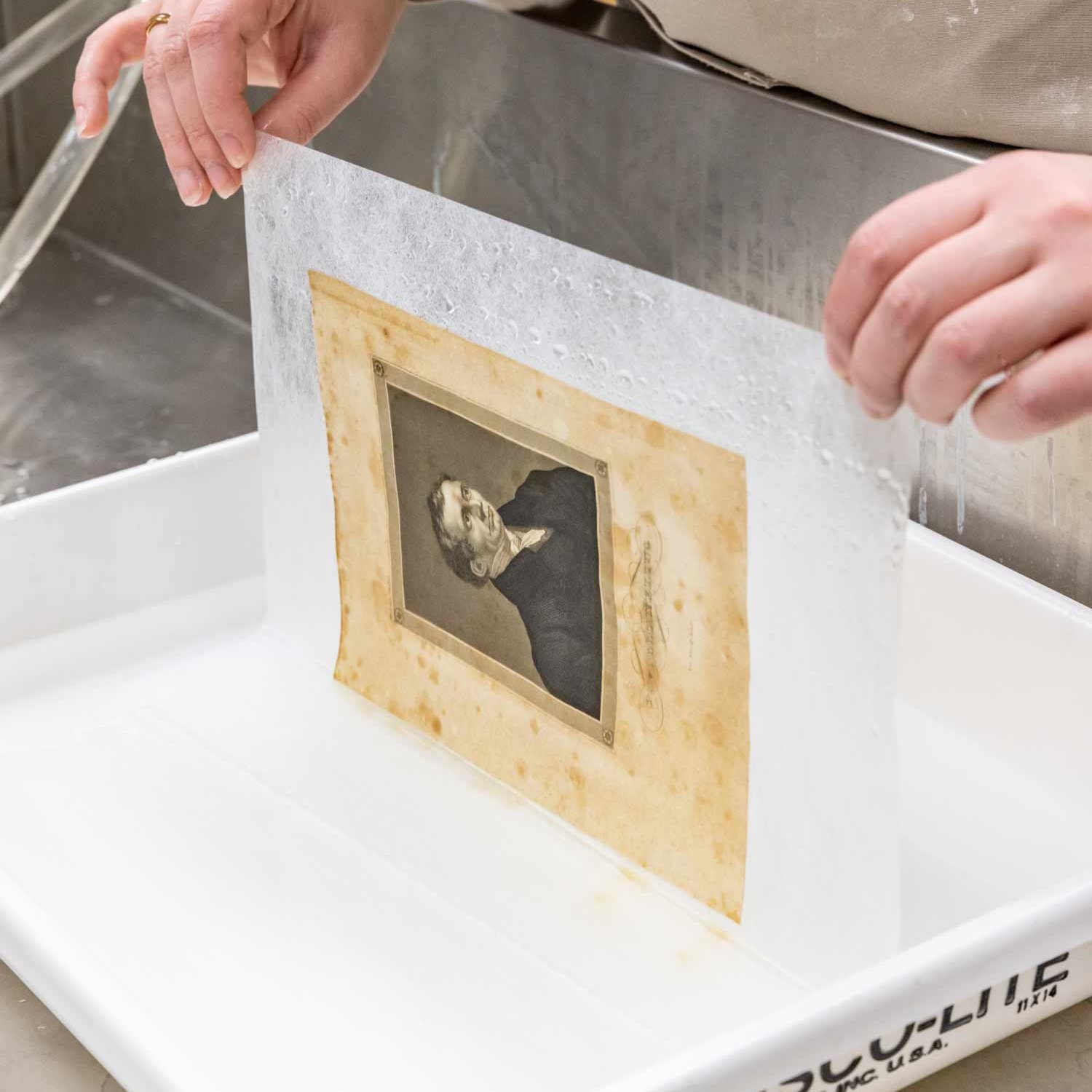

Print-making is a process for mass producing art and images. Most prints in Colonial Williamsburg’s collection were created with a technique called intaglio printing (Italian for engraving). This involved engraving an image onto a metal plate using a sharp tool, filling the engraved lines with ink, placing the plate and paper on a rolling press, and applying pressure. This transferred the ink to the paper, capturing the intended design. Color printing was not widely available until the second half of the 19th century. Most prints in the collection were hand colored with watercolor by professional colorists before they were sold to consumers.

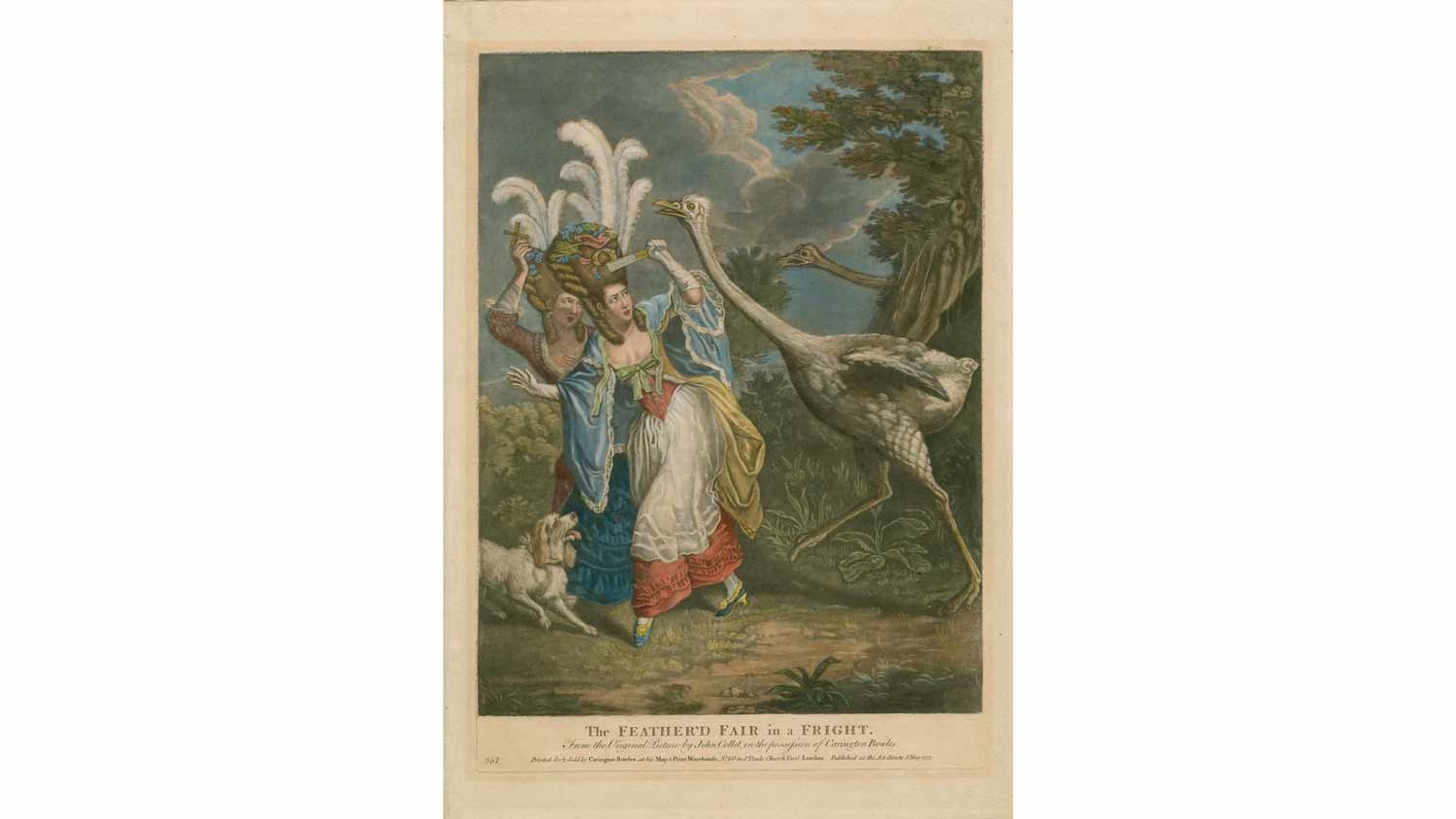

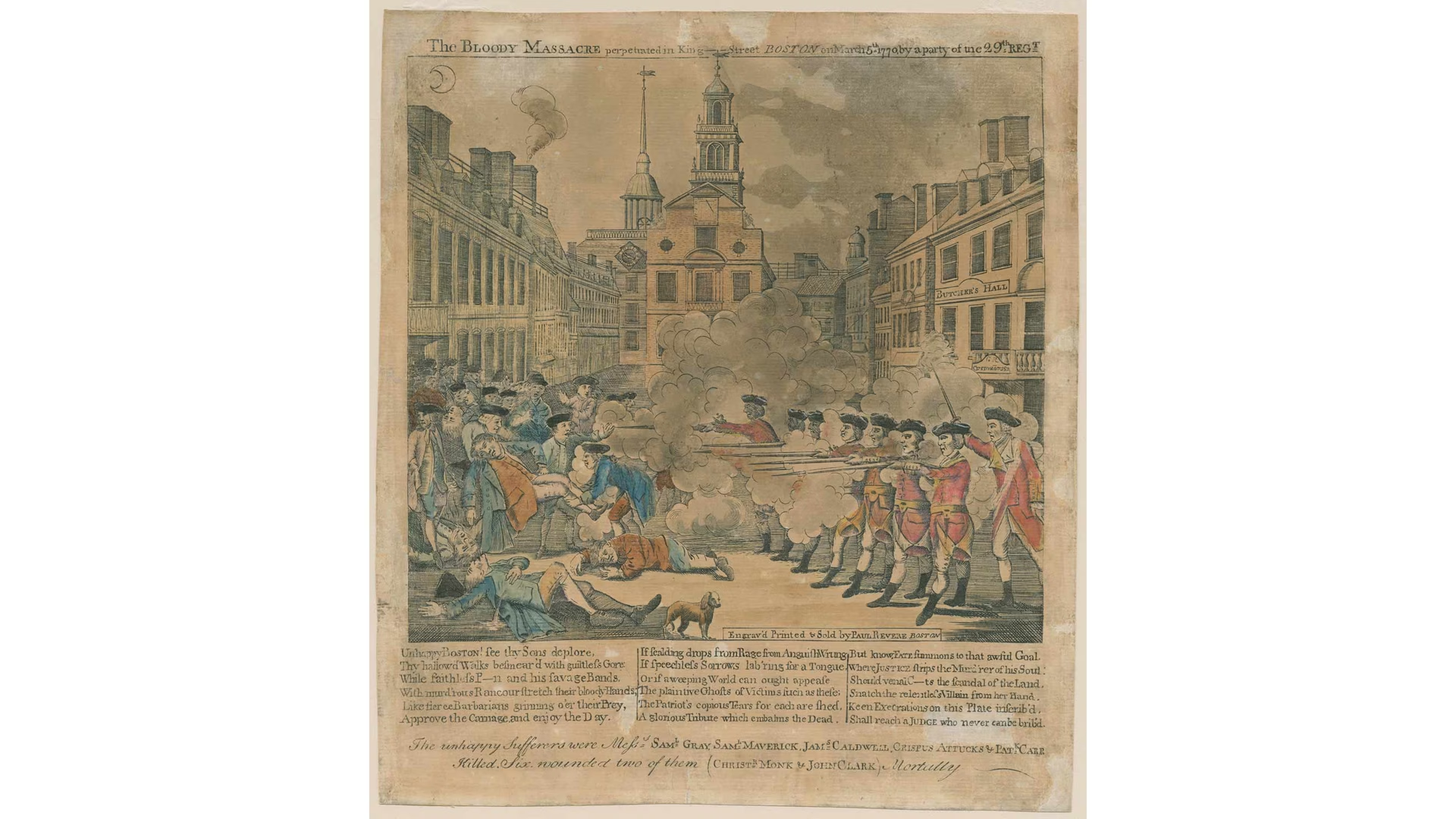

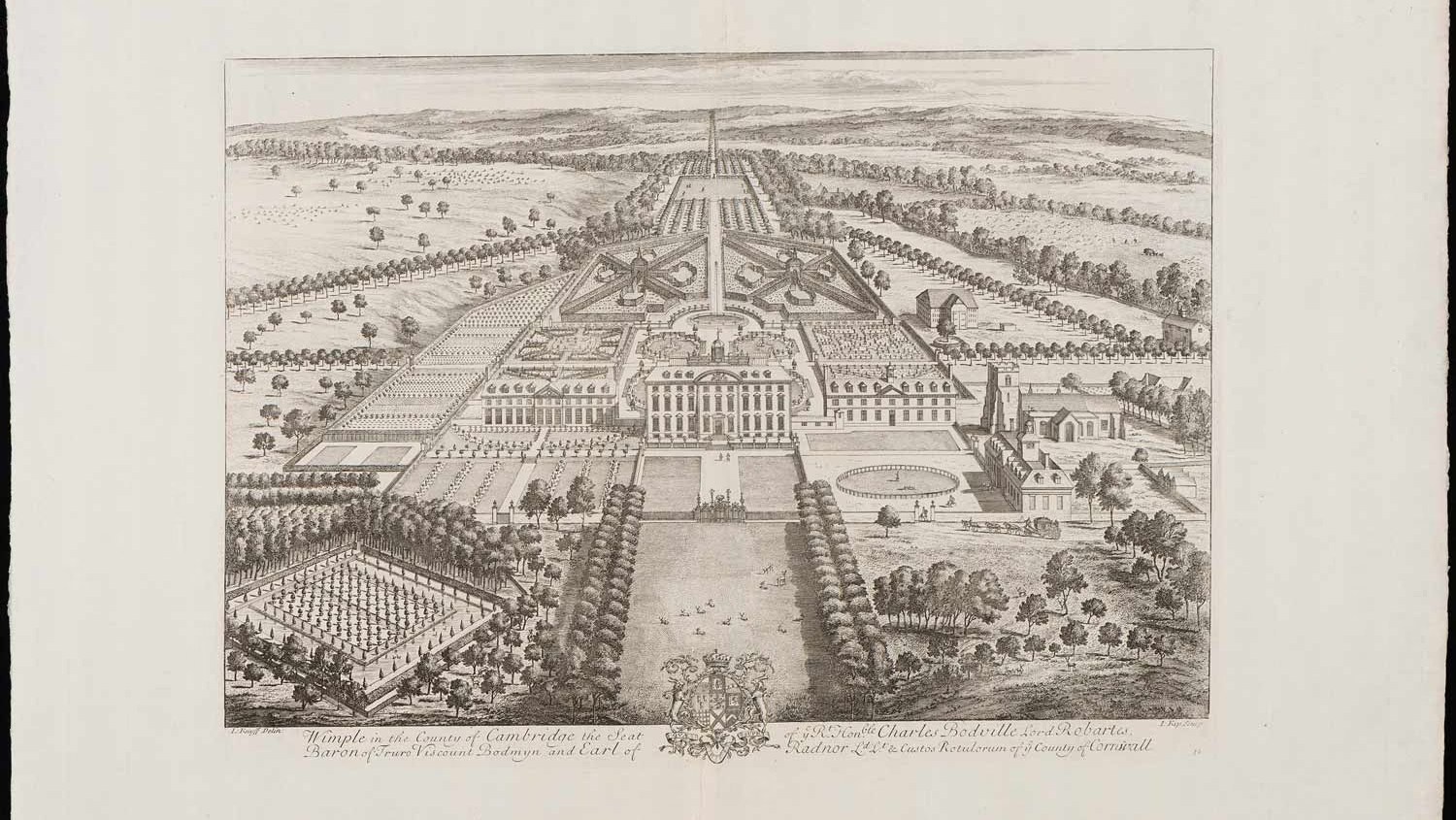

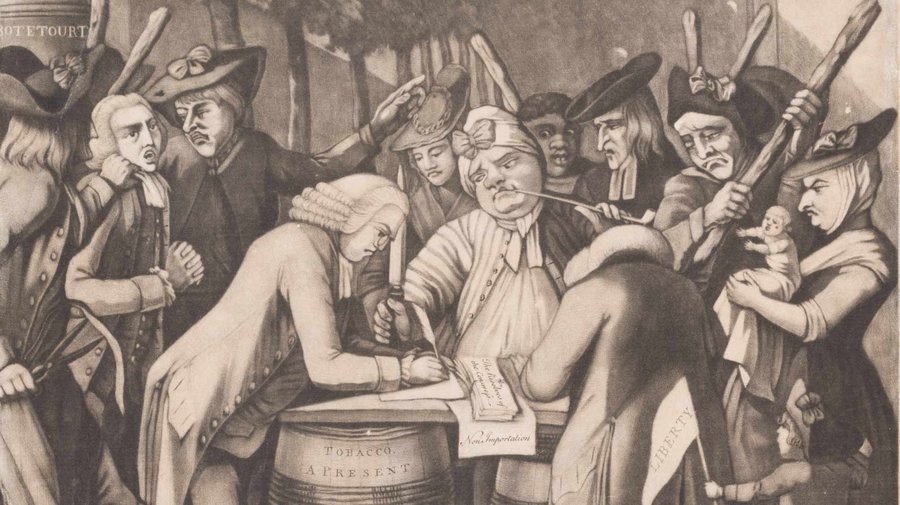

Engraved images enabled rapid reproduction, allowing a single image to be mass-produced and widely shared. For example, a print based on a painting of a famous person could be shared and seen across an empire. Prints also served as a crucial source of knowledge for information-hungry British subjects. They used prints to associate faces with names, decorate homes and businesses, entertain through satirical imagery, advertise products, share knowledge about the natural world, visualize faraway places, or spread political ideas.

Highlights from the Collection

Prints depicted a variety of subjects, including natural history, politics, portraits, history, current events, places, satire, and more.

What do prints tell us about the past?

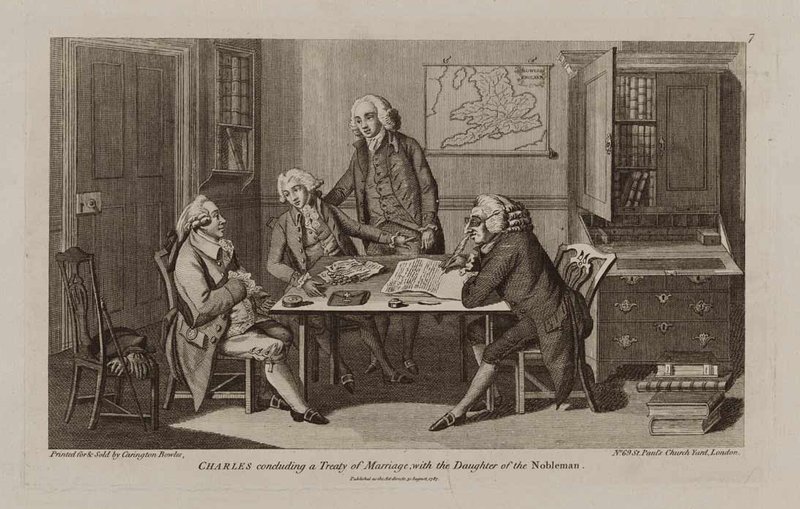

Today, historians and curators learn a great deal about the past through prints. Prints provide details about everyday life that weren’t always mentioned in writing. For example, they show how people used certain objects or wore certain clothes, or how furniture might have been arranged in a room. How people interacted with each other and social expectations can also be studied through prints.

Scholars use prints like this to glean details about daily life, including decorations and clothing. “CHARLES concluding a Treaty of Marriage, with the Daughter of the Nobleman,” 1787. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

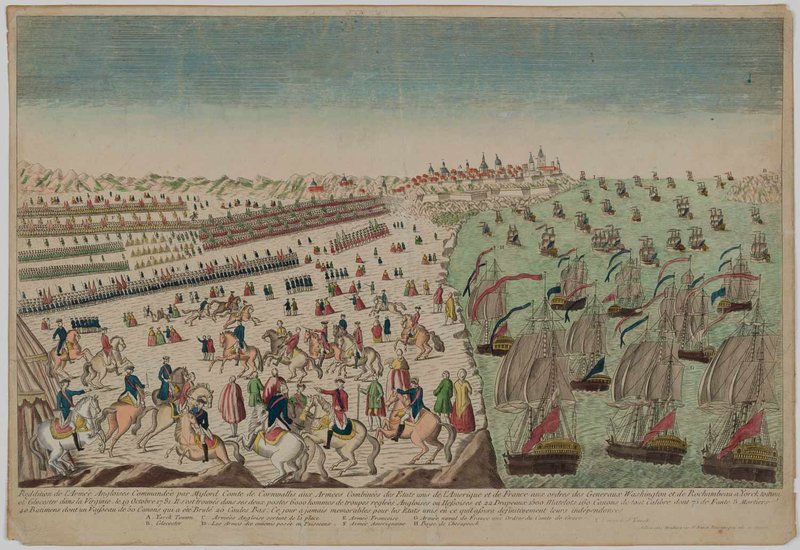

However, the study of prints is not without its challenges. One such challenge is that many prints, even those depicting American scenes, were produced in London by artists who had never visited America. Some details in these prints are more fictional than factual, resembling scenes that could be from fantasy novel rather than an accurate American landscape. This discrepancy reminds us that while prints are informative, they also have their limitations.

Printmakers capitalized on current events, at times depicting scenes with only scarce details. This French print of the 1781 surrender at Yorktown shows the event in an imagined Europeanized setting. For example, the city in the background resembles a fortified European city more than the actual city of Yorktown. “The Surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown,” ca. 1781. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

Explore Prints

The Alternative of Williams-Burg

Furber's Flowers

Visscher’s Print of America

Call it Macaroni

Achieving Fame

Celebrity in Print

This exhibition features prints of notable figures, whose fame and celebrity rose as news and portraits of them spread around the globe through print.