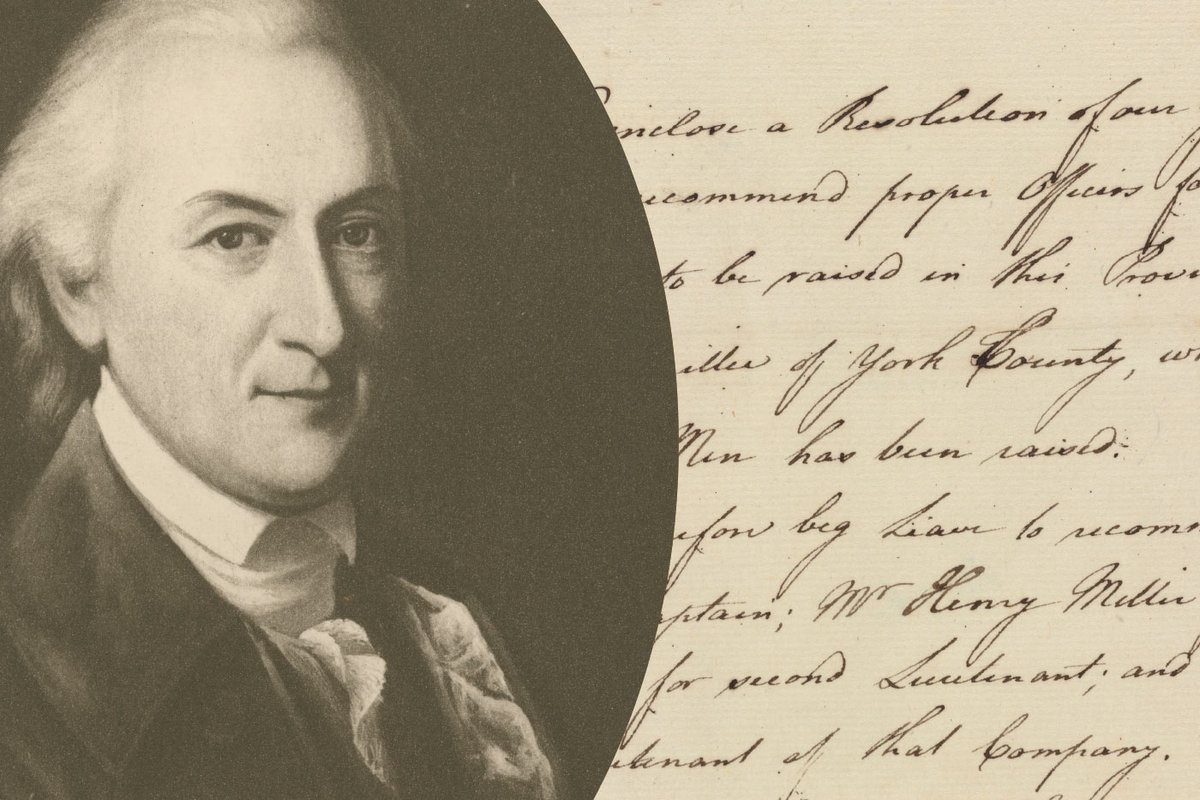

A Moderate Revolutionary

Often misrepresented as resisting the Revolution, Dickinson crafted two of the fledgling nation’s important documents

John Adams dismissed John Dickinson as a “piddling Genius,” but history tells a more complex story. Overshadowed by louder, more radical voices like Adams’, the more moderate Dickinson nonetheless played a pivotal role in the early years of the American Revolution, navigating the delicate line between protest and diplomacy. He clashed with Thomas Jefferson as well as Adams, but with a pen as sharp as his convictions, he shaped some of the most critical documents of the era.

While Adams and Jefferson became household names, Dickinson’s contributions as a quiet force helping to shape the nation’s founding principles remain largely overlooked. That is unfortunate because Dickinson played a key role in drafting the Second Petition from Congress to the King, better known as the Olive Branch Petition, and the Declaration of the Causes and Necessity for Taking Up Arms. These two documents justified to colonists and the world the necessity of armed resistance.

Extending an Olive Branch

The Olive Branch Petition came about in May 1775 when the Second Continental Congress authorized the preparation of a conciliatory petition to King George III. The petition attempted to delicately balance assertiveness and reconciliation in a tense political climate.

Congress appointed a committee of five to draft the petition. The committee included Dickinson and Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania and John Jay of New York. Their task was to craft a document that would prevent further bloodshed while also asserting colonial grievances.

Jay took the lead on the first draft, drawing inspiration from letters by New York Chief Justice William Smith Jr. and a recent petition from the New York General Assembly. Jay’s version criticized Britain’s post-French and Indian War governance and Parliament’s overreach. Many in Congress also believed Britain had gone too far, but Jay’s draft failed to rally broad support.

When Jay’s draft fell short, Dickinson stepped in. Dickinson had authored “Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania, to the Inhabitants of the British Colonies,” a series of essays published in 1767 and 1768 against the Townshend Acts. Dickinson’s “Farmer’s Letters” were reprinted throughout the colonies. His ability to craft persuasive, unifying language and his reputation for galvanizing public support through his writings made Dickinson the ideal choice for the delicate enterprise of improving Jay’s draft.

To enrich and enhance the New Yorker’s work, Dickinson used materials that had influenced Jay. For example, one of Jay’s inspirations was Smith’s letter to Lewis Morris. Dickinson’s final draft of the Olive Branch Petition contains similar wording to the letter. And Dickinson likely drew on another source Jay used: a petition to George III that the New York General Assembly adopted on March 25, 1775, that denied Parliament’s right of taxation without the colonists’ or their representatives’ consent and questioned the legality of laws passed since the end of the French and Indian War.

While Dickinson did build on Jay’s draft, there were several striking differences between the two men’s work. For example, Jay suggested suspending “every irritating Measure” whereas Dickinson demanded the outright repeal of offensive statutes. Jay urged King George III to appoint “good & great Men” to investigate colonial grievances while Dickinson called for a for-mal process to ensure a “happy and permanent reconciliation.” Where Jay’s language hesitated, Dickinson’s was assertive yet diplomatic.

Dickinson also ensured that the delegates signed the document as individuals rather than as representatives of their colonies — a subtle gesture aimed at reinforcing the personal devotion of America’s leaders to their monarch. Careful not to make unnecessary admissions or concessions, Dickinson crafted a petition that balanced loyalty with firm resolve. On July 5, 1775, Congress approved the Olive Branch Petition with little debate, sending it across the Atlantic in a final attempt to avert an escalation of the war.

Not everyone in Congress supported the Olive Branch Petition. Adams, one of its most vocal critics, viewed the petition as overly cautious. He only begrudgingly signed it. Adams later noted his opposition: “There were different opinions concerning the Petition to the King in the Year 1775.” Those “different opinions” would deepen into a public rift between Adams and Dickinson, underscoring the ideological divides within Congress during this tumultuous time.

Adams would later include in his autobiography a lengthy description of Dickinson’s activities against him during the Continental Congress. According to Adams, Dickinson had been urged to oppose Adams’ “designs.” Adams later recalled a heated exchange with Dickinson over the Olive Branch Petition, a moment that cemented their fraught relationship for the rest of their lives. Adams wrote in his autobiography that he “was opposed to [the Olive Branch Petition], of course; and made an Opposition to it, in as long a Speech as I commonly made.” Dickinson, Adams reported, “began to tremble for his Cause.”

Shortly after he delivered a speech against the Olive Branch Petition, Adams departed Congress, but as he made his way out, Dickinson chased after him. “He broke out upon me in a most abrupt and extraordinary manner,” Adams wrote, adding:

In as violent a passion as he was capable of feeling, and with an Air, Countenance and Gestures as rough and haughty as if I had been a School Boy and he the Master, he vociferated out, “What is the Reason Mr. Adams, that you New Englandmen oppose our Measures of Reconciliation. There now is Sullivan in a long Harrangue following you, in a determined Opposition to our Petition to the King. Look Ye! If you dont concur with Us, in our pacific System, I, and a Number of Us, will break off, from you in New England, and We will carry on the Opposition by ourselves in our own Way.”

Adams was stunned but kept his cool. In his autobiography, he recalled his response to Dickinson:

Mr. Dickenson, there are many Things that I can very chearfully sacrifice to Harmony and even to Unanimity: but I am not to be threatened into an express Adoption or Approbation of Measures which my judgment reprobates. Congress must judge, and if they pronounce against me, I must submit, as if they determine against You, You ought to acquiesce.

These were likely the last words that John Adams and John Dickinson exchanged in private. From that moment on, they had a strictly professional relationship.

Sparring with Jefferson

Dickinson soon came into conflict with a young lawyer from Virginia on the Declaration of the Causes and Necessity for Taking Up Arms.

On June 21, 1775, Jefferson joined the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia. Days later, Congress appointed a committee to draft a declaration justifying armed resistance. Its members included Franklin, Jay and John Rutledge of South Carolina. This declaration, intended for Gen. George Washington’s army, would explain to colonists and the world why the colonies had taken up arms.

The committee’s first attempt, led by Rutledge, failed to capture the urgency and gravitas Congress sought. On June 26, the task was recommitted, this time with two new voices: Jefferson, the eloquent newcomer from Virginia, and Dickinson, the seasoned Pennsylvania statesman renowned for his pen. Congress hoped their combined talents would produce a declaration with the power to inspire and unite — a call to arms that would stir both soldier and civilian.

For two weeks, Jefferson and Dickinson sparred over the draft. Jefferson started with Rutledge’s version in hand, but his initial effort drew criticism. William Livingston quipped that Jefferson’s work was typical of “our Southern gentlemen,” filled with lofty rhetoric but lacking gravitas.

Dickinson, known for his clarity and precision, reviewed Jefferson’s draft, annotating it with suggestions and corrections in the phraseology as well as several queries about other points that might be added to the report. Jefferson rejected all the suggestions and accepted only one or two of Dickinson’s language edits. Despite Jefferson’s resistance, however, the back and forth between the two men did sharpen their respective visions for the declaration.

When Jefferson submitted his draft to the full committee, it did not advance. Evidently, some members agreed with Dickinson that Jefferson’s version lacked the necessary punch. The committee enlisted Dickinson to prepare another text.

Instead of starting from scratch, Dickinson reworked Jefferson’s draft. He retained Jefferson’s structure and many of his passages but made revisions that provided clarity and emotional resonance. For example, Dickinson’s straightforward approach led him to write, “we mean not to dissolve that Union,” while Jefferson was more verbose, writing, “we mean not in any wise to affect that union with them.” When speaking of independence, Dickinson was equally blunt: “Necessity has not yet driven us into that desperate Measure.” Jefferson, on the other hand, had written, “That necessity must be hard indeed which may force upon us this desperate measure.”

Dickinson’s aim was to create a cohesive and compelling declaration that would appeal to both skeptical colonists and potential allies abroad. To that end, he sharpened the document’s rhetoric and added memorable flourishes. One striking addition proclaimed: “Our cause is just. Our union is perfect. Our internal Resources are great, and, if necessary, foreign Assistance is undoubtedly attainable.”

Historians have long debated whether Jefferson’s draft failed for being too radical or whether Dickinson was overly conservative. More likely, their collaboration blended Jefferson’s idealism with Dickinson’s pragmatism. Together, they created a document that balanced colonial grievances with a commitment to reconciliation, laying the groundwork for broader support.

On July 6, 1775, Congress approved Dickinson’s draft with minor revisions. Copies were quickly sent to Boston, where Washington shared the declaration with his troops to bolster morale. From there, it spread like wildfire across the colonies, rallying support for the cause. By October, translations had reached European capitals, where the document underscored the colonies’ resolve and their appeals for foreign alliances.

How Jefferson and Dickinson remembered this moment in their political lives gave birth to an authorship dispute. In 1801, Dickinson claimed authorship of the declaration in the introduction to his collected Political Writings. He insisted that all documents attributed to him in the volumes were indeed his work, stating that he would never take credit for writings he did not compose.

Jefferson made two notable statements regarding the declaration’s authorship. In an unpublished note, which scholars believe Jefferson likely wrote before the publication of Dickinson’s Political Writings, Jefferson recalled that Dickinson had been asked to “retouch” his draft, suggesting some degree of collaboration or revision. Decades later, in his 1821 autobiography, Jefferson provided a conflicting account, asserting that Dickinson rejected his draft as too strong, rewrote it entirely and retained only the final four and a half paragraphs. This later account, written when Jefferson was 78, contains demonstrable errors but nonetheless influenced generations of historians.

Historians have often portrayed the Jefferson-Dickinson collaboration as a clash of ideologies, with Jefferson representing radicalism and Dickinson conservatism. However, a closer examination reveals a partnership that blended their strengths. Jefferson brought ambition while Dickinson grounded the document in practical diplomacy.

Their combined efforts produced a declaration that was neither radical nor timid but instead a masterful balance of defiance and conciliation. It resonated widely, rallying support for the Continental army and signaling to the world that the colonies were prepared to fight — but still hoped for peace. Dickinson’s efforts have often been overlooked, and his name kept from the roster of the nation’s most important influences, but his quiet brilliance is a reminder that the Revolution was not just fought on battlefields — it was also written into history with words.

More from this Issue