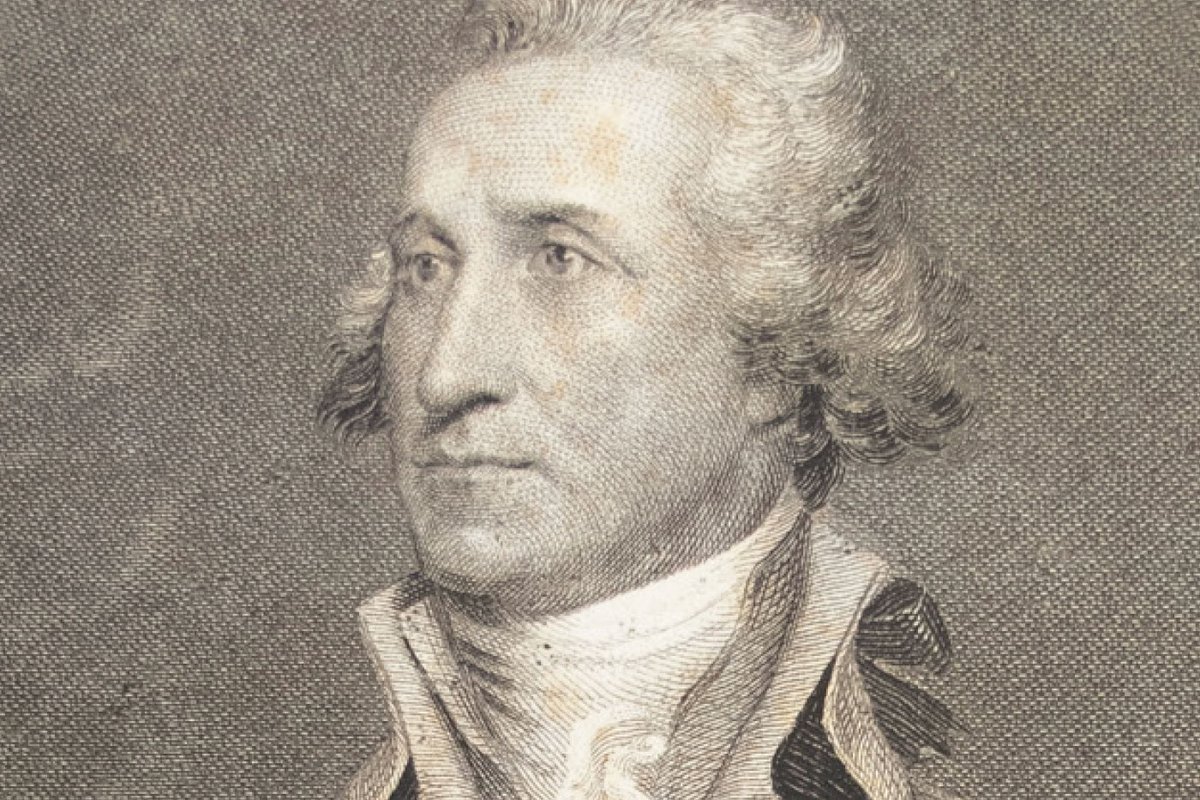

The Reintroduction of George Washington

A pivotal moment allayed colonial fears about the first commander in chief

“I heard Bulletts whistle and believe me there was something charming in the sound,” wrote 22-year-old Virginia militia officer George Washington in 1754.

George Washington’s expedition to dislodge the French in the disputed western territory around what is now Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, unexpectedly elevated him to the world stage. News of his exploits spread throughout the colonies and even reached King George II of England, and before long Washington was a hero to Anglo-Americans and a villain to the French. But two decades after the French and Indian War, Washington’s name recognition had diminished in America and essentially vanished throughout Europe. The American Revolution reintroduced Washington to the world.

On June 15, 1775, the Continental Congress elected Virginia delegate George Washington as the commander in chief of the new Continental army. On the surface, Washington — a hero of the French and Indian War and the only person in the room dressed as a military officer — seemed an obvious choice. Being the tallest man in the room did not hurt either, nor did Washington’s Southern origins, which Massachusetts delegate John Adams believed would help unite the colonies. After Maryland delegate Thomas Johnson nominated Washington, Adams wrote to his wife, Abigail, “This Appointment will have a great Effect, in cementing and securing the Union of these Colonies.” But exactly what sort of commander in chief the colonies needed was still up for debate.

The next day, Washington was formally commissioned inside the Pennsylvania State House, later known as Independence Hall. Standing before the delegates dressed in the bluff and blue uniform of the Virginia militia, Washington was charged with one overarching mission: “the defence of American Liberty.”

After Gen. Washington humbly accepted the “high Honour” and promised to serve Congress in “Support of the glorious Cause,” delegates like John Adams and John Hancock, president of the Second Continental Congress, praised his character and countless attributes. He was a “fine man,” a man “you will all like,” described in terms like brave, virtuous, modest, amiable, clever, and sober, steady, and calm.

However, these words were expressed only in private correspondence. Congress was sworn to secrecy about Washington’s selection, and Hancock was adamant that not a word should “be put in the newspaper” out of fear that “some prejudices might arise.” No matter how Washington’s character might be praised, there was doubt and fear about the role of commander in chief. The new army needed a leader, but colonists had plenty of historical reasons to wonder how its new commander in chief might use — or abuse — his power.

It did not take long to get the answer.

In a speech before the New York Provincial Congress on June 26, 1775, Gen. George Washington denounced military dictatorship. He would give up power as a general in 1783 and once more as president in 1797, but this moment at the outset of the Revolutionary War was critical. It signaled Washington’s commitment to civilian rule and the peaceful transition of power and dispelled deep-seated fears of domestic tyranny. It also established Washington’s most important precedent right from the start.

The stakes might not seem high to modern Americans who know how the story ends, but in the spring of 1775, colonial Americans’ fears about a standing army were deep-seated. They dated back to the classical era when Julius Caesar crossed the Rubicon, waged war against the Roman Republic and declared himself dictator for life in 49 B.C.E. Over 1,700 years later, during the English Civil War, Oliver Cromwell defeated royalist forces, dismissed Parliament and proclaimed himself Lord Protector for life in 1653. Based on historical evidence, American colonists had been holding their breath since the first royal force disembarked to restore order after Bacon’s Rebellion in Virginia in 1677, all the way to the arrival of Gen. Edward Braddock’s force to fight the French in 1755.

Heightening the colonists’ fears, Boston had been under military occupation since 1768, and the famed tossing of tea into the harbor had triggered martial law in 1774. One political cartoon of the time, printed in The Royal American Magazine, even depicted the British military actively assisting the ravaging of America. The battles of Lexington and Concord the following spring were, as Virginian Thomas Jefferson proclaimed, unprovoked murder. With the outbreak of war, it was understood that appointing a commander in chief was essential, but the colonists believed a military savior could quickly become a tyrant.

It would have allayed the colonists’ fears to know that — unlike the British-born, title-chasing Charles Lee or the immensely wealthy Hancock — Washington had never campaigned to be commander in chief. Sure, he wore his uniform to Congress, but the delegates — many of whom had served with him on both congresses — knew him as a modest man who ran out of the room when his name was discussed for general. And in private, Washington wrote of his appointment, “It is an honour I by no means aspired to.” This was the type of person Congress could trust to be “vested with full power and authority to act as you shall think for the good and welfare of the service,” as was stated in his commission. Congress never explicitly mentioned any fear over the role of commander in chief, perhaps because such concerns were so well-known that they did not need to be written down. Still, the wording of Congress’ charge to Washington and his commission was deliberate. They did not ask the general to win glory or to destroy the British army. Rather, the commander in chief’s duty was to be the defender of American liberty and follow the orders of Congress.

But while Hancock hoped to keep the news of Washington’s commission out of the papers, the general’s review of 2,000 Pennsylvanian soldiers performing the manual of arms on the Philadelphia common made that impossible. The first notice of Washington’s new role as commander in chief appeared in The Pennsylvania Gazette on June 21, 1775. While details about Washington were sparse, the newspaper did point out that this power came from Congress. Two days later, The Virginia Gazette in Williamsburg offered a brief excerpt from a congressman who was “deeply impressed with” Washington’s recognition of “the importance of that honourable trust.” It would take a few more days, but the New York media would give Washington a more compelling story and a wider audience.

On June 26, 1775, Washington paraded into New York City on his way to take command outside Boston. The recently created patriot New York Provincial Congress arranged to meet with the new commander in chief that afternoon at his lodgings near King’s Bridge in what is now the Bronx. Under the leadership of President Peter Van Brugh Livingston, who had two brothers serving in the Continental Congress, nearly 60 delegates crafted an address that offered the general many hearty congratulations but also revealed anxiety over what Washington could become. “We rejoice in the Appointment of a Gentleman,” the Provincial Congress stated, “from whose Abilities and Virtue we are taught to expect both Security and Peace.” The subtext was clear: Was American liberty safe? Could Washington be trusted?

Unlike the Continental Congress, the New Yorkers had not sat beside Washington in Carpenters’ Hall or the State House over the past two years. They did not know Washington, and instead of addressing him as commander in chief or general, they opted for “generalissimo,” a title dating back to the early 17th century that implied a blend of military and political power. A generalissimo was a “supreme and absolute commander,” defined in military dictionaries of the time as having been “first invented by the absolute authority of Cardinal Richelieu,” a clergyman chief minister under King Louis XIII of France. In the English legal tradition, “generalissimo” was tied to a king, and just so happened to be a title associated with Cromwell.

The New York Provincial Congress quickly got to the real issue, wrapping their loaded question — Would Washington give up power after the war? — in a statement saying they had “the fullest Assurances that whenever this important Contest shall be decided,” the commander in chief “will chearfully resign the important Deposit committed into Your Hands, and reassume the Character of our worthiest Citizen.”

The New Yorkers were not only referencing their fear of a Caesar or Cromwell but also offering an example to be followed: Roman patrician-turned-dictator-turned-farmer Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus. In 458 B.C.E., the Roman Senate granted Cincinnatus dictatorial powers to save the republic from an invasion. While some feared that Cincinnatus would take advantage of the authority granted to him, the victorious leader lay down his sword after only 16 days and returned home. Could America expect the same?

Washington, who was well-versed in classical history, clearly understood what was being asked. He knew the story of Cincinnatus and recognized the “important Trust” given to him. Privately, he had pledged three things after his appointment: “a firm belief of the justice of our Cause — close attention in the prosecution of it — and the strictest Integrety.” New York was his opportunity to make the same declaration publicly.

Washington responded to the New York Provincial Congress with the same blend of modesty and self-doubt regarding his appointment that he had displayed before the Continental Congress. Yet his answer was clear. Washington assured them that when he and the army “assumed the Soldier, we did not lay aside the Citizen, & we shall most sincerely rejoice with you...when the establishment of American Liberty...shall enable us to return to our private Stations in the bosom of a free, peaceful, & happy Country.” Washington left no doubt he would protect America and then return home to Mount Vernon. He had pledged to be an American Cincinnatus.

Livingston was so struck by this message that he immediately requested a written copy of Washington’s speech, saying he wanted to “prevent mistakes” from distorting this declaration when he made it public. Perhaps he also wanted to ensure Washington kept his word. So, despite Hancock’s unrealistic instruction to keep Washington’s appointment out of the papers, Livingston and the New York Provincial Congress ordered their address and Washington’s words printed that evening.

Three days later, on June 29, 1775, Washington was presented more widely to the American public via The New-York Gazette and The New-York Journal, soothing American fears. His words spread quickly on both sides of the Atlantic, and by early August 1775, news of Washington’s appointment could be found in British newspapers such as The Derby Mercury and The Bath Chronicle of England and The Caledonian Mercury of Scotland. But while much of the British press simply reprinted American articles without editorializing, the New York speech prompted a Washington-Cromwell comparison from The Scots Magazine, based in Edinburgh. “When Oliver Cromwell was made Generalissimo of the parliament-army in K[ing] Charles I.’s time,” it read, “he soon made himself master of the government.” The press recognized that Washington’s intent was “to obviate” such fears and “any apprehension of a similar event” in America.

Considering that Washington was committing treason and commanding a “rebel-army,” his British reception was shockingly positive. British audiences knew of Cincinnatus too, of course, and in the months around Washington’s appointment, the London papers were filled with references to the heroic Roman, sometimes in connection to the American cause. The St. James’s Chronicle, for example, remarked that colonists had read their Cincinnatus and the British were therefore “warmed with the noble Flame of Liberty” and “charmed with Sentiments worthy of the first Citizens of Rome.”

Although British officers often refused to address “Mr. Washington” by his rank, his character was still praised. The American commander was “a gentleman of affluent fortune,” as the reference yearbook The Annual Register said, and one “who had acquired considerable military experience.” Not only had he “positively refused any pay” serving his cause as a volunteer, The Scots Magazine gushed, but “he is a man of sense and great integrity.” The press even indulged in a bit of tabloid journalism by remarking on Washington’s “exceeding fine figure” and “very good countenance.” Most surprisingly, Lloyd’s Evening Post described him as “a most noble example” who was “worthy of imitation in Great Britain” for being a “disinterested Patriot.” Washington’s pledge to give up power seemed to be equally effective in Britain as it was in America.

Washington took up command of the Continental army on July 3 in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The Massachusetts Provincial Congress “applauded[ed]” his “attention to the public good” and “admire[d]” his “disinterested Virtue.” Barely a week removed from the New York speech, the delegates praised his “personal Character” for risking his life and fortune “in the Defence of the Rights of Mankind, and for the good of your Country.” This devotion to civilian supremacy became Washington’s trademark throughout the long war.

Even after eight years of fighting, some in England still assumed that Washington would end up as a king or “the Dictator, Protector, Stadtholder, or by whatever Name the Chief Magistrate.” Americans like Philadelphia socialite Elizabeth Willing Powel knew better: “Some say there is no Cincinnatus in existence; I think there is.” She would be proven correct.

On Dec. 23, 1783, Gen. George Washington once again stood before the members of Congress in his buff and blue uniform. His hair was grayer, and his sight had worsened. Still, he possessed confidence that he had successfully “accomplish[ed] so arduous a task” and defended American liberty. In 1775, Washington had accepted the “extensive & important Trust” Congress afforded him with his commission. Now, he surrendered his commission back to the congressmen assembled inside the Maryland State House in Annapolis and took his “leave of all the employments of public life.”

When King George III learned that his enemy intended to give up power, he was genuinely amazed and reportedly said, “If he did, he would be the greatest man in the world.” Washington fulfilled his pledge and did exactly that.

George Washington was now the American Cincinnatus, just like he promised on June 26, 1775.

More from this Issue