The Gunpowder Incident and the Collapse of Royal Government in Virginia

The drums were beating. The streets were pulsing. Early on the morning of April 21, 1775, Williamsburg’s residents spilled out from their homes looking for the cause of this commotion.

Everyone soon heard that Virginia Governor John Murray, the Fourth Earl of Dunmore, had seized the colony’s gunpowder supplies. Expecting this, the people of Williamsburg had been warily watching the city’s Magazine for months. But for white Virginians, Dunmore’s timing was especially outrageous. That spring, rumors were spreading daily about insurrections and resistance among the colony’s hundreds of thousands of enslaved people. The governor had disarmed them, white Patriots claimed, just as a Black-led revolt was stirring.

The threat of bloodshed simmered throughout the spring and summer of 1775. The crisis ultimately ended with little violence. But the Gunpowder Incident set in motion the flight of Governor Dunmore and the eventual collapse of the colony’s royal government. The revolution had come to Virginia.

Enslaved Resistance

The enslaved people who lived along Virginia’s James River began to resist their condition more openly in late 1774 and early 1775. Reports spread of insurrections throughout the region. In Chesterfield County, white inhabitants were described as “alarm’d for an Insurrection of the Slaves.” In Norfolk, two enslaved men were convicted of leading a revolt. In Prince Edward County, an enslaved man named Toney was punished with fifteen lashes for planning an insurrection. Similar events were reported in Norfolk and in the Northern Neck. In Williamsburg, one enslaver recorded that there were “some disturbances in the City, by the Slaves.”1 Details of these events are obscure. Perhaps hoping to avoid publicizing these incidents, enslavers spoke vaguely about them. Some reports may have also been exaggerated.2

Yet by the spring of 1775, white Virginians were increasingly concerned about the threat of a general insurrection of enslaved people. As tensions grew within the British empire, some Virginia colonists suspected that colonial leaders were sowing discontent among the colony’s enslaved population.3 Were these instances of resistance evidence of a coordinated plan? Conspiracies thrived.4 A group of Virginia leaders would soon explain to Dunmore that they had “reason to believe that some wicked and designing persons have instilled the most diabolical notions into the minds of our slaves.”5

Seizure of the Gunpowder

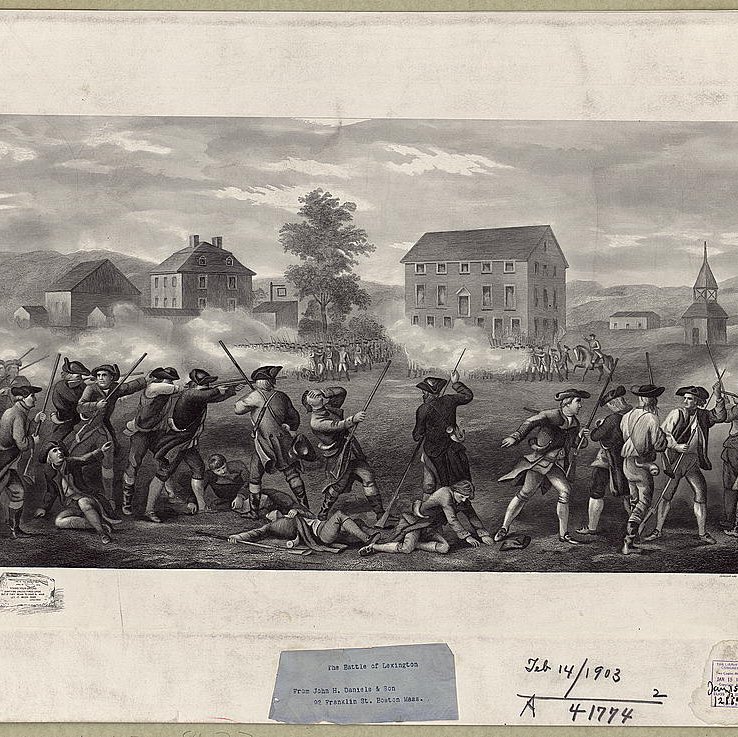

As tensions escalated between colonists and colonial authorities in 1775, both sides began to look ahead to the possibility of a war. In January, the Virginia Gazette reported that royal governors like Dunmore had been ordered to take control of colonial gunpowder supplies.6 When Massachusetts Governor Thomas Gage moved to seize the colonial militia’s supplies of gunpowder and weapons in Concord, his actions sparked the Battle of Lexington and Concord on April 19.

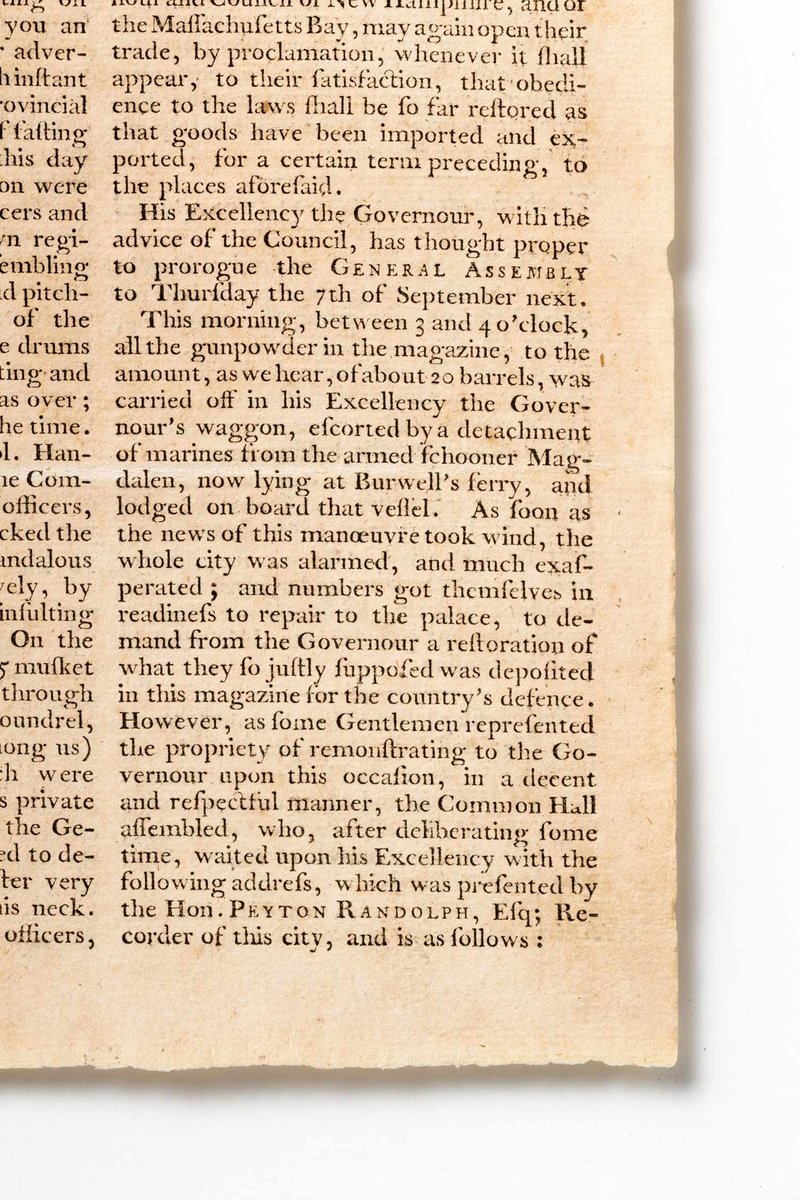

Located at the center of the capital city, Williamsburg’s Magazine was a symbol of royal strength. It contained the colony’s supply of gunpowder, as well as an array of firearms and swords. Though unaware of events in New England, rumors of an imminent seizure caused some Virginia volunteers to guard the Magazine and protect its contents from Dunmore’s troops. Yet according to a later historian, these guards eventually lost interest and “grew a little negligent.”7 With the guard lapsed, Dunmore ordered a group of royal sailors to remove the Magazine’s gunpowder supplies and store them aboard a nearby naval vessel. Between three and four o’clock in the morning of April 21, the sailors entered the Magazine and seized fifteen half-barrels’ worth of gunpowder. They also disabled the guns stored there by removing the firelocks.8

Angry Streets

When the people of Williamsburg learned about the seizure of the gunpowder, an alarm swept through town. Many saw Dunmore’s action as a betrayal. He had disarmed Virginia’s white colonists just as they felt most threatened by the colony’s enslaved people. An angry crowd assembled near the Governor’s Palace. The city’s militia company assembled. For a moment, it seemed as if a mob might storm the Palace.9 But the town’s leaders stepped in. A group that included Peyton Randolph convinced the crowd to stand down while they asked the governor for an explanation. When a delegation met with Dunmore, he explained that he had secured the powder following a report of a nearby insurrection of enslaved people. He promised to return the powder if it was needed to defeat a rebellion.10 Separately, in a later letter to his superiors in London, Dunmore offered a different explanation for the seizure of the gunpowder. He explained that he believed the angry free colonists, who had pursued a “series of dangerous measures” against the government, were planning to seize the gunpowder as part of their efforts to overturn the government.11

Dunmore’s explanation and promise appeased the town’s leaders. They convinced the mob to disperse. Though we don’t know how they managed this, it’s likely that they understood that an attack on the governor would risk destabilizing their slave society. Dunmore made this clear two days later. He told one visitor to the Palace that if he or his men faced further “Injury or insult,” “he would declare Freedom to the Slaves, and reduce the City of Williamsburg to Ashes.” He predicted that if violence broke out, the “Majority of white People and all the Slaves” would join “the side of Government.” Accounts of Dunmore’s threats spread widely, further inflaming resistance to British rule.12

Militias

Disturbed by accounts from Williamsburg, free Virginians mobilized themselves into volunteer militia units across the colony. By early May, they heard news of the Battle of Lexington and Concord to the north. They were coming to see themselves as participants in a war. In Hanover County, the volunteer militia elected Patrick Henry as its leader. They marched toward Williamsburg.13

Hearing about the approach of these militiamen, Dunmore threatened again to emancipate the colony’s enslaved people.14 Williamsburg’s elite leaders desperately tried to convince Henry and his militia to turn back. After much negotiation, Henry finally accepted their advice after Thomas Nelson Jr., a member of the colony’s Council, signed a promissory note to reimburse the colony for the value of the gunpowder taken.15 Henry later explained that he viewed “the outrage on the magazine” to be “a most fortunate circumstance,” because it would “rouse the people from north to south.”16

Collapse of Royal Government

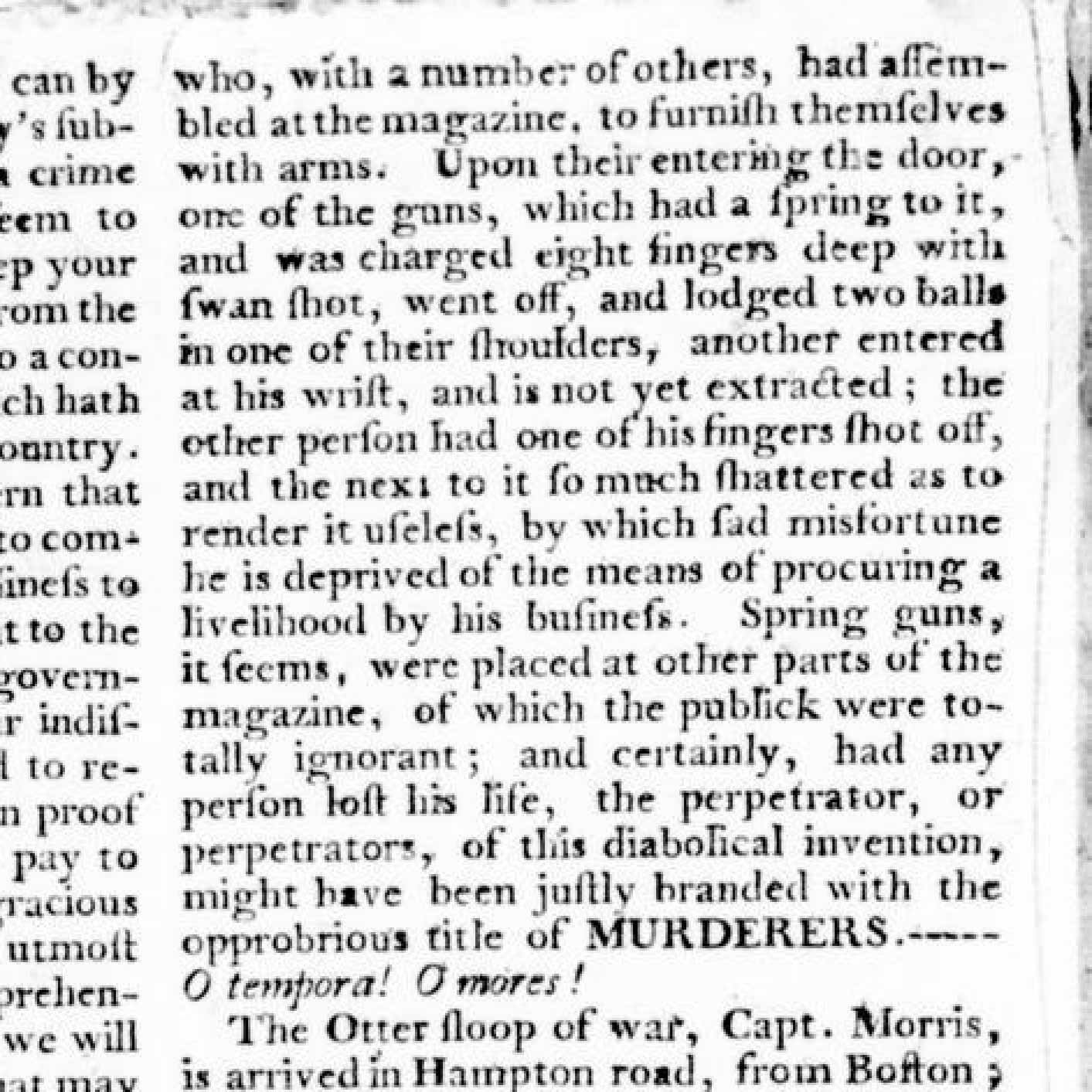

After Henry’s militia departed, an unsteady peace returned to Williamsburg. But on the night of June 3, a group of young men broke into the Magazine. Someone, likely with Dunmore’s knowledge or approval, had outfitted the building with a trap shotgun. When the group entered the Magazine, they tripped a spring that caused the gun to discharge “swan shot” at them. Several of the young men were seriously wounded.17

This incident led to a fresh wave of public outrage. Rumors spread. A group of colonists raided the Magazine again. The town’s militia rose up. In the face of this tidal wave of criticism, Dunmore had become increasingly alarmed for his safety. He feared he would be assassinated, or his home would be attacked.18 On the dark, humid morning of June 8, Dunmore led his family out of the Palace and onto a nearby naval vessel called the Fowey. They would never return to Williamsburg. Though Dunmore attempted to exercise his authority from aboard the Fowey for months afterward, his departure from Williamsburg effectively marked the end of royal government in Virginia.19

Powder and Power

Despite the explosive name it has long carried, Virginia’s “Gunpowder Incident” was a slow burn that ended in anticlimax. Unlike in Massachusetts, where competition for military supplies caused the Battles of Lexington and Concord, Virginians narrowly avoided large-scale violence. Even after Dunmore’s departure, it took a year for Virginians to write a new constitution to replace the royal government. Patrick Henry was chosen as Virginia’s first elected governor.

The gradual collapse of the colony’s political order allowed Virginians to preserve the system of slavery upon which their economy and society rested. But if the gunpowder crisis marked the collapse of royal government in Virginia, it also marked the beginning of new possibilities for the colony’s enslaved people. Governor Dunmore’s threats during the gunpowder crisis were the first hints of the strategy he would pursue in November 1775, when he offered freedom to enslaved people who joined the British forces. Dunmore’s Proclamation brought reality to the possibilities of freedom that were stirring in the spring of 1775.

1775 Gunpowder Incident

This is the event that sparked the Revolution. So many of the events at the core of our nation's origin story happened here in Williamsburg.

The Powder Magazine

The Powder Magazine was constructed in 1715 as storage for the arms and ammunition dispatched from London for the defense of the colony. Just before the Revolution, it was the scene of a famous confrontation between Williamsburg residents and the royal governor, when his soldiers absconded with the colony's gunpowder.

Sources

- On Toney, see Philip J. Schwarz, Twice Condemned: Slaves and the Criminal Laws of Virginia, 1705–1865 (Louisiana State University Press, 1988), 181–85; Michael McDonnell, The Politics of War: Race, Class, and Conflict in Revolutionary America (Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, 2007), 50; Robert G. Parkinson, The Common Cause: Creating Race and Nation in the American Revolution (Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, 2016), 83.

- On the question of evaluating reports of conspiracies and insurrections among enslaved people, see Jason T. Sharples, The World That Fear Made: Slave Revolts and Conspiracy Scares in Early America (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020).

- Woody Holton, Forced Founders: Indians, Debtors, Slaves, & the Making of the American Revolution in Virginia (Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1999), 143.

- One newspaper writer, looking back on these incidents, commented “Whether this was general, or who were the instigators, remains as yet a secret.” “To the Publick,” Virginia Gazette (Purdie), June 16, 1775, p. 1, link.

- “Municipal Common Hall to Governor Dunmore: An Humble Address,” in Robert Scribner, ed., Revolutionary Virginia: The Road to Independence, vol. 3: The Breaking Storm and the Third Convention, 1775 (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1977), 55.

- “Newport, Dec. 12,” Virginia Gazette (Dixon and Hunter), Jan. 14, 1775, p. 1, link.

- John Burk, The History of Virginia: From Its First Settlement to the Present Day (Dickson and Pescud, 1805), 3:409.

- Journals of the House of burgesses of Virginia 1773-1776, ed. John Pendleton Kennedy ([E. Waddey Co.], 1905), 223, link. William Wirt, Sketches of the Life and Character of Patrick Henry (James Webster, 1817), 135.

- Dunmore to Lord Dartmouth, May 1, 1775, in “The Magazine (LL) Historical Report, Block 12 Building 9,” Colonial Williamsburg Digital Collections, p. 39.

- ““Governor Dunmore to the Municipal Common Hall An Oral Reply,” in Scribner, ed., Revolutionary Virginia, 3:55.

- Dunmore to Lord Dartmouth, May 1, 1775, in “The Magazine (LL) Historical Report, Block 12 Building 9,” Colonial Williamsburg Digital Collections, p. 39.

- Journals of the House of Burgesses of Virginia, 1773–1776 ([E. Waddey co.], 1905), 231, link.

- McDonnell, Politics of War, 64.

- Journals of the House of Burgesses of Virginia, 1773–1776 ([E. Waddey co.], 1905), 231, link.

- McDonnell, Politics of War, 64.

- Wirt, Sketches of the Life and Character of Patrick Henry, 137.

- Virginia Gazette (Purdie), June 9, 1775, supplement, p. 2, link.

- John E. Selby, The Revolution in Virginia, 1775–1783 (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1988), 42–43.

- Selby, Revolution in Virginia, 43.