Powder Magazine

Temporarily closed for restoration. The Magazine was constructed to store the arms and ammunition dispatched from London for the defense of the colony. Just before the Revolution, it was the scene of a famous confrontation between Williamsburg residents and the royal governor, when his soldiers absconded with the colony's gunpowder. Check back for more information on the building reopening to the public.

What Was a Magazine?

Wars and rebellions were a constant threat in eighteenth-century Virginia. Colonists fought other European powers, including France and Spain. They battled nearby Native nations, including the Cherokees and the Shawnees. And Virginia’s white colonists guarded constantly against the perceived threat of violent resistance from thousands of enslaved people. Threats seemed to be everywhere, and so military supplies, and their security, was urgent.

Despite being often known as the “Powder Magazine” or “Powder Horn,” the Magazine held much more than gunpowder in the eighteenth century. Across its three floors, the structure also stored items such as guns, mess kits, and tents.

Building the Magazine

Despite the importance of such weapons, Virginia’s Lieutenant Governor Alexander Spotswood complained in 1712 that “Most of the Arms are unserviceable and the powder very much decayed.”1 Two years later the colonial assembly agreed to build “one good substantial house of brick” to house “all the arms, gun-powder, and ammunition, now in the colony, belonging to the king.” Construction would be financed through a tax on liquor and on the importation of enslaved people into the colony.2 The Magazine building was completed by early 1716, or earlier. It was quickly filled with supplies sent from London.

In 1755, amid tumult caused by the French and Indian War, Virginia’s government paid for a permanent guard to patrol the Magazine. They built a Guardhouse and “a high and strong” protective perimeter wall.3 Yet as the war came to an end, the assembly decided to spare the colony the expense of maintaining the guard. Suddenly out of work, the poorly paid guardsmen petitioned the assembly to be allowed to keep their arms.4 Government leaders denied this request. Rather than being left unattended, the arms and other supplies were sold.5

The Magazine and the American Revolution

As tensions rose between the colonists of Virginia and the colonial government in the 1770s, the Magazine became a flashpoint of resistance. After Dunmore dissolved the House of Burgesses in the spring of 1774, colonists had become increasingly assertive in their protests against the British empire. Additionally, rising resistance among the colony’s enslaved people stoked new fears. In the spring, rumors spread that Virginia Governor John Murray, the Fourth Earl of Dunmore, was about to seize the colony’s gunpowder supply. A group of volunteers kept guard over the Magazine for several days but eventually lost interest. Early in the morning of April 21, 1775, at Dunmore’s orders, a crew of sailors took fifteen half barrels of gunpowder to a nearby vessel and disabled many of the firearms stored in the Magazine.

The seizure of the gunpowder provoked a furious response. Local leaders barely managed to prevent the city’s residents, and later a militia led by Patrick Henry, from attacking the Governor’s Palace. A few weeks later, after Williamsburg calmed, a group of young men broke into the Magazine. A spring-gun rigged to shoot at intruders discharged at the group, wounding several of them.6 Public tempers flared again. This time, fearing for their safety, Governor Dunmore and his family slipped out of the Governor’s Palace at night and made their way to a nearby naval ship, never to return to Williamsburg.

After Dunmore’s flight, colonists moved the guns and swords usually held in the Palace to the Magazine and dispensed them to the public.7 In the years following the Gunpowder Incident, the Magazine came to serve as a supply depot for the Continental Army.8 Once a symbol of royal power located in the center of the capital of its largest North American colony, the Magazine had now become an instrument of revolution. Indeed, the events that unfolded at the Magazine helped to set in motion the collapse of royal government in Virginia. As Patrick Henry later wrote, the “robbery of the magazine” did more to “rouse the people” and “bring the subject home to their bosoms” than any talk of tea taxes and abstract principles.9

The Gunpowder Incident

How did royal government collapse in Virginia? The Gunpowder Incident sparked a crisis that brought revolution to Britain’s largest North American colony.

This image, taken by an unknown photographer in the late nineteenth century, depicts the Magazine while it was used as a livery stable.

Afterlife

After Virginia’s government transferred to Richmond, the Magazine took on many afterlives. It was used as a market house, as an arsenal during the Civil War, as a livery stable, and as a temporary location for a Baptist church. When the congregation decided to build their own church building in 1855, they are believed to have used parts of the Magazine’s perimeter wall to construct it.10

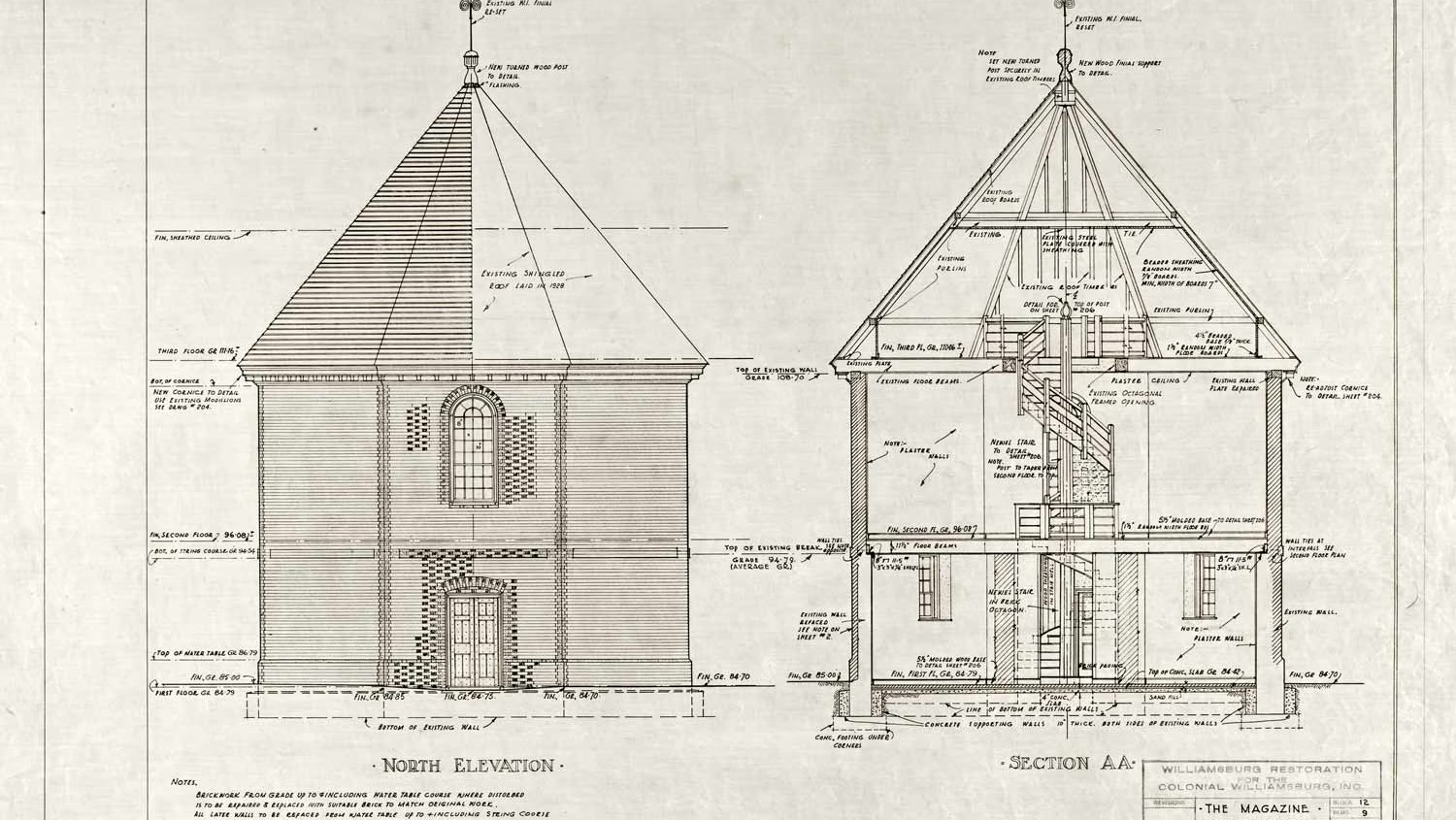

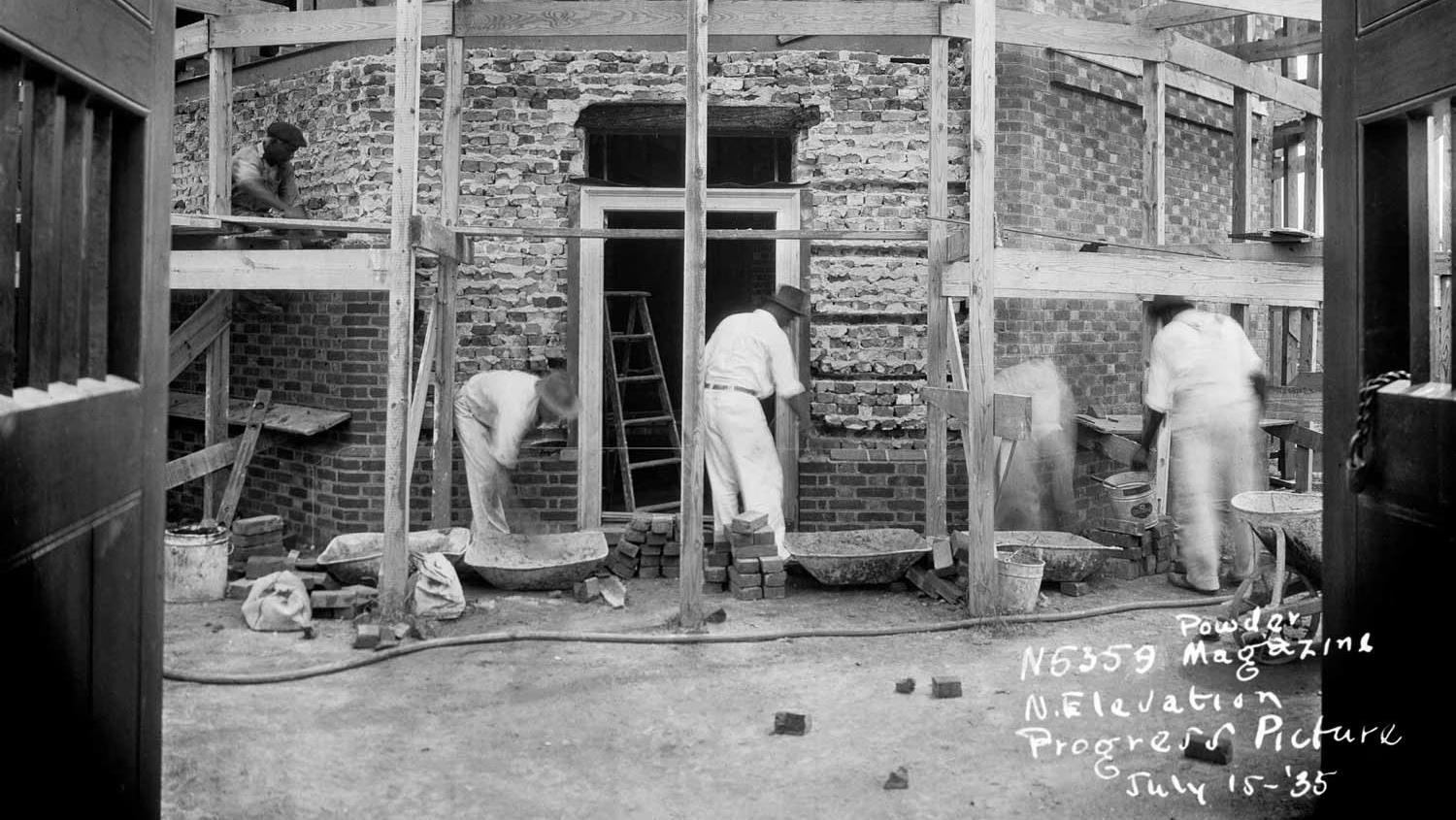

Initial Restoration

The Powder Magazine is one of the 89 original buildings in Colonial Williamsburg’s Historic Area. The restored Magazine and reconstructed Guardhouse opened to the public in 1949.

Sources

- “An account of Arms & Ammunition belonging to her Majesty within the Colony of Virginia,” Colonial Office 5/1316.

- William Waller Hening, ed., Statutes at Large: Being a Collection of all the Laws of Virginia, from the First Session of the Legislature, in the Year 1619 (Franklin Press: 1820), 4:55-56, link.

- Hening, ed., Statutes at Large, 6:528, link.

- John Pendleton Kennedy, ed., Journal of the House of Burgesses of Virginia, 1761–1765 (Colonial Press, 1907), 163, link.

- Hening, ed., Statutes at Large, 8:146, link.

- John E. Selby, The Revolution in Virginia, 1775–1783 (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1988), 42–43.

- Selby, Revolution in Virginia, 43.

- Selby, Revolution in Virginia, 46.

- H. R. McIlwaine, ed., Journals of the Council of the state of Virginia (Virginia State Library, 1931), 278, link.

- William Wirt, Sketches of the Life and Character of Patrick Henry (McElrath & Bangs, 1833), 155.

- H. Bullock, “The Magazine (LL) Historical Report, Block 12 Building 9,” Colonial Williamsburg Digital Collections.

- “Architectural Report, Public Magazine,” (revised 1952), Colonial Williamsburg Digital Collections, p. 2, 19.