A Time Traveler’s Guide to Early American Taverns

Down the Road, where it swept to the right to go round the foot of the hill, there was a large inn. [The Prancing Pony] had been built long ago when the traffic on the roads had been far greater . . . The company was in the big common-room of the inn. The gathering was large and mixed, as Frodo discovered, when his eyes got used to the light. This came chiefly from a blazing log-fire, for the three lamps hanging from the beams were dim, and half veiled in smoke . . . On the benches were various folk: men of Bree, a collection of local hobbits (sitting chattering together), a few more dwarves, and other vague figures difficult to make out away in the shadows and corners.

J. R. R. Tolkien, The Fellowship of the Ring (1954)1

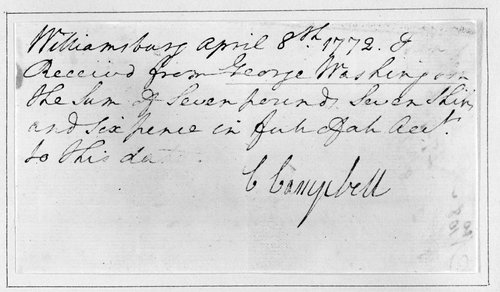

Shields Tavern

Early American taverns brought out the best and the worst in humanity. They were important social venues where visitors could meet, mix, and amuse themselves. But taverns also harbored inequality and violence. In taverns, people both created communities and built barriers to protect those communities from the dangers of the unknown. Going to a tavern in eighteenth-century America meant navigating this contradiction.

Though taken from a fantasy series about hobbits, wizards, and a magical ring, the above quotation describes these enduring inconsistencies with surprising accuracy. At a crossroad, the Prancing Pony draws travelers and locals alike. Its dim, smoke-filled “common room” reflects this wide appeal, with a “large and mixed” company of men, hobbits, and dwarves drinking beer and sharing stories.

But even fantasy stories reflect the real world, warts and all. A danger of the “other” lurks in the Prancing Pony, where a group of “local hobbits” separate themselves from “vague figures” lingering in the “shadows and corners” of the common room. Whether in timeless Middle Earth or eighteenth-century Virginia, taverns were vital venues for social cohesion and exclusion. Like the humans who built and inhabited them, these public venues proved paradoxical. Nowhere better mirrored colonial America’s social complexity than the tavern.

Amenities and Activities

William Breton’s illustration of eighteenth-century Philadelphia displays the sale of enslaved African people on a tavern’s front porch. William L. Breton, “Stoker's, Old London Coffee House” (Philadelphia: 1830). Courtesy of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Taverns weren’t just for drinking. They were the most numerous, accessible, and popular public spaces in the British American colonies. Taverns multiplied as more settlers poured into British America and built new towns, ferries, and farms. Eighteenth-century cities like Williamsburg kept roughly one licensed tavern for every 100 to 130 residents.2 Simple services for travelers remained the bedrock of the tavern trade: visitors could expect to find a drink, meal, bed (usually shared with at least one person, often a stranger), horse stables, and plenty of conversation. They might also obtain a loan, purchase a ticket for an upcoming horse race, or participate in a politically charged group conversation. Globally sourced beverages such as rum punch, wine, coffee, chocolate, and tea became popular in taverns, as did access to foreign news, traveling entertainers, and public auctions.3

Julius Caesar Ibbotson, Sailors Carousing (ca. 1805). National Maritime Museum (London, U.K.) Caird Collection.

Darker avenues of commerce also drove taverns’ profit. In 1769, for instance, more than fifty enslaved people were prizes in a lottery held at Wetherburn’s Tavern in Williamsburg. This was the grisly reality of colonial America: tavern goers might sip wine and gossip while men, women, and children were bought and sold only feet away.

Rum, the most popular liquor in colonial taverns, was a product of the deadly exploitation of people, environments, and animals on Caribbean sugar plantations. “The Devil was in the English-man,” as one enslaved Caribbean laborer exclaimed, “that he makes everything work; he makes the Negro work, he makes the Horse work, the Ass work, the Wood work, the Water work and the Winde work.”4 Global networks of trade allowed colonial American taverngoers to consume the sweet products of these deadly efficient plantations. But long-distance trade also separated consumers from the brutal production process. Out of sight, out of mind.

Patrons and Matrons

Taverns were not for everyone. Colonial leaders regulated who could enter taverns and what they could do there. Non-white peoples and women served tavern customers but did not serve as customers. White women like Jane Vobe and Christiana Campbell, for example, kept successful taverns in Williamsburg.5 Yet, at the same time, women were unofficially barred from drinking in taverns. They might occasionally lodge in taverns, or attend a ball with their husband, but only under intense scrutiny. When Sarah Kemble Knight traveled from Boston to New York in 1704, she faced constant questions during her tavern stays. “I never see a woman on the Rode [road] so Dreadfull late, in all the days of my . . . life,” one female tavern worker asked her: “Who are You? Where are You going?”6

This was also true of non-white colonists. Enslaved people produced food and drink in the kitchens, cared for horses in the stables, and ensured customers’ satisfaction in the parlor. Yet they were denied access to those same comforts. Some of the enslaved peoples sold on a tavern porch might very well have worked at a nearby tavern, as taverns’ inventories regularly featured Black people alongside dishes, barrels of rum, and mahogany tables. When the Williamsburg tavern keeper James Shields passed away in 1750, “25 Negroes” were listed right next to “1 grindstone,” and “a Parcel of Corn Tobacco and Pease” in his tavern’s material record.7

Rural Recreation, Urban Enlightenment

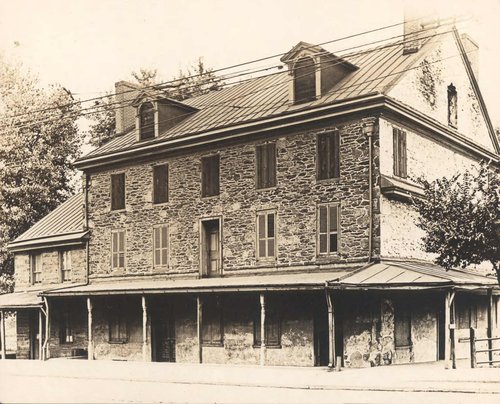

The Blue Bell Tavern was a rural ordinary south of Philadelphia. Image courtesy of the Library Company of Philadelphia.

Location was everything. Usually resting near a ferry or crossroads (recall the Prancing Pony), rural taverns had to serve far-flung foreigners and loquacious locals alike. Rural tavern keepers accordingly diversified their businesses. George Frey of Middletown, Pennsylvania, for instance, not only kept tavern, but also milled wood and sold a variety of globally sourced goods. Frey, and so many other rural tavern keepers like him, connected their patrons to the world while also creating a backcountry community.8

Urban taverns, meanwhile, became more specialized. As cities prospered, tavern keepers crafted environments where a select clientele might find like-minded company. Lower-class taverns were usually huddled around the docks, serving sailors, workers, and low-brow businessmen. More elitist establishments, meanwhile, also prospered. Seeking to distance themselves from their supposed inferiors, wealthy colonists funded exclusive City Taverns and Coffee Houses in cities such as Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Charleston. These venues were open to only a select group of private subscribers.9 They would eventually evolve into exclusive urban hotels.10

Yet another sector of urban taverns existed beyond the bounds of propriety, let alone legality. Unlicensed taverns, scornfully termed “disorderly” or “bawdy” houses by officials, allowed enslaved peoples, women, and servants to congregate outside of the law and develop alternative networks of sociability and community.11 Yet the gentlemen who derided these “disorderly” taverns also served as some of their most reliable customers. Elite men often went on “the rake,” drunkenly destroying property and assaulting guests in lower class taverns.12 At times, these same men took their disorderly behavior into otherwise “orderly” tavern spaces. In 1712, for example, the Virginia plantation owner William Byrd II noted that “several of our young gentlemen” had to pay a considerable fine “for a riot committed last night at Su Allen’s” Williamsburg tavern.13 Some might have wondered: weren’t the alleged “lower sorts” supposed to be the colonists who committed such unruly acts in public spaces? British America was rich in contradictions.

Space, Age

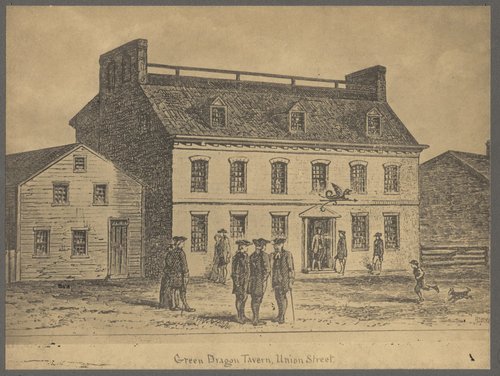

Boston’s Green Dragon Tavern (a name that might have also been taken from a Tolkien novel) was a popular meeting place for revolutionaries. Courtesy of the Boston Public Library.

Taverns were colonial America’s premier public spaces, offering endless opportunities for sociability, consumerism, and drunken revelry. But, unlike Tolkien’s Prancing Pony, American taverns were real places, inhabited by real people, who had real problems. Crowded taverns witnessed heated debates about who should hold power in society. Eventually, many of these disputes helped instigate the American Revolution.14

America no longer supports any public spaces quite like taverns. Today, you would have to visit a restaurant, bar, hotel, gas station, public library, bank, and even social media to do everything you could at one eighteenth-century tavern. No matter. Taverns live on in spirit if not crumbling brick and mortar. Their fading popularity still testifies to the constant human desire for connection and consumption, no matter the cost.

Experience the atmosphere and lifestyle of Virginia’s colonial capital city in the Historic Area, and immerse yourself in the flavors of Colonial Williamsburg at our historic taverns.

Sources

Cover image: Isaac Weld, “American Stage Wagon,” from Travels through the states of North America… (London: 1799). Courtesy Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

- J. R. R. Tolkien, The Fellowship of the Ring (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1987; 1954), 164–67.

- Vaughn Scribner, Inn Civility: Urban Taverns and Early American Civil Society (New York: New York University Press, 2019), 21–41; Kirsten E. Wood, Accommodating the Republic: Taverns in the Early United States (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2023), 46–83, 117–34.

- Emma Hart, Building Charleston: Town and Society in the Eighteenth-Century British Atlantic World (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2010), 1-4; Vaughn Scribner, “‘Quite a Genteel and Extreamly Commodious House’: Southern Taverns, Anxious Elites, and the British American Quest for Social Differentiation,” Journal of Early American History 5 (2015): 39.

- [Anonymous], “Great Newes from Barbadoes” (London: L. Curtis, 1676), 6-7. See also Neil Oatsvall and Vaughn Scribner, “‘The Devil Was in the Englishman that He Makes Everything Work’: Implementing the Concept of ‘Work’ to Reevaluate Sugar Production and Consumption in the Early Modern British Atlantic World,” Agricultural History 92:4 (Fall 2018): 461–90.

- Linda L. Sturtz, Within Her Power: Propertied Women in Colonial Virginia (London: Routledge, 2002), 96.

- Sarah Kemble Knight, "The Journal of Madam Knight.," in The Puritans, ed. Perry Miller and Thomas H. Johnson. (New York: American Book Company, 1938), 425-427. See Clare A. Lyons, Sex among the Rabble: An Intimate History of Gender and Power in the Age of Revolution, Philadelphia, 1730-1830 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 32, 59, 123, 281; Sharon V. Salinger, Taverns and Drinking in Early America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004), 24, 55, 112–15, 152–53, 171–72.

- See, for instance, “An Inventory of the Estate of James Shields deceased,” Colonial Williamsburg Digital Library, accessed June 19, 2024. For historians’ explorations of non-white people’s exclusion from taverns, see Peter C. Mancall, Deadly Medicine: Indians and Alcohol in Early America (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1995), 19, 47; Peter Charles Hoffer, The Great New York Slave Conspiracy of 1741: Slavery, Crime, and Colonial Law (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2003), 44-64, 86, 112.

- David J. Hancock, “The Triumphs of Mercury: Connection and Control in the Emerging Atlantic Economy,” in Soundings in Atlantic History: Latent Structures and Intellectual Currents, 1500-1830, ed. Bernard Bailyn and Patricia L. Denault (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009), 121.

- Peter Thompson, Rum Punch and Revolution: Taverngoing and Public Life in Eighteenth-Century Philadelphia (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999), 19, 147-73; David S. Shields, Civil Tongues and Polite Letters in British America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997), 18, 56-70; Scribner, Inn Civility, 21-41.

- A. K. Sandoval-Strausz, Hotel: An American History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), 43.

- Serena R. Zabin, Dangerous Economies: Status and Commerce in Imperial New York (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009), 48–64; Lyons, Sex among the Rabble, 61–107; Salinger, Taverns and Drinking, 112–30.

- Scribner, Inn Civility, 103-8.

- William Byrd II, The Secret Diary of William Byrd of Westover, 1709-1712, ed. Louis B. Wright and Marion Tinling (Richmond, VA: Dietz Press, 1941), 517.

- Benjamin L. Carp, Rebels Rising: Cities and the American Revolution (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 62–98; Scribner, Inn Civility, 109–70.