The Founders’ Vision for an Informed Citizenry

Today, it’s hard work staying on top of current events. But this was even more difficult during the 1700s.

Information wasn’t equally available to everyone in eighteenth-century America. Not everyone had the opportunity to go to school. Not everyone could afford a newspaper subscription. Not everyone communicated with far-flung correspondents. And of course, not everyone had free time to spend on matters of public interest. Even among those who could easily access information, many could be misinformed by rampant rumors and false reports.1

America’s Founders recognized that one of the most dangerous challenges to their young republic was an uninformed or misinformed population. In the aftermath of American independence, the Founding generation pursued two different paths to address this challenge. Some aimed to protect the republic from its people’s ignorance. Others sought to inform, educate, and enlighten Americans.

From Subject to Citizen

In colonial America, few people needed to be deeply informed about current events. Loyalty to the British crown did not require much knowledge about public affairs. Instead, many elites feared that informing or educating the public could have dangerous consequences. For example, Virginia Governor Sir William Berkeley commented in 1671, “I thank God, there are no free schools nor printing [in Virginia] . . . for learning has brought disobedience . . . into the world.”2

New England Primer (1773). Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Not everyone agreed with this view. In New England, especially, colonists supported public education and invited ordinary people to participate in governance through town meetings.3 But in many colonies, including Virginia, education was divided into two tracks: private academies training elite young men to join the ruling class, and charity schools that aimed to create a better workforce.4

Black Education in Williamsburg

Description: Schools for enslaved and free Black children, like the Williamsburg Bray School, focused on preparing students for work, rather than educating them as citizens.

The American Revolution began to change this. Looking to history, many political leaders saw examples of dangerous demagogues seizing power by manipulating and deceiving uninformed ordinary people. How could the Founders prevent the republic from following that path?5

Making the Constitution

Americans disagreed about how much power ordinary people should have in the government. But for some, the disorder of the United States following the Revolutionary War, including a rebellion in western Massachusetts that became known as Shays’s Rebellion, proved that ordinary people were too easily misled by “Demagogues of desperate fortunes.” Some powerful leaders worried as they saw states adopt what they regarded as short-sighted policies such as paper money and debtor relief.6

Howard Chandler Christy (1940). Courtesy of the Architect of the Capitol.

At the 1787 Constitutional Convention, delegates often noted the risks of creating a government that could be dominated by an uninformed public. For example, George Mason observed in a debate over the Electoral College, “The extent of the country renders it impossible that the people can have the requisite capacity to judge” between candidates, making a deliberative body necessary.7 Connecticut delegate Roger Sherman opposed popular election of senators because: “The people . . . should have as little to do as may be about the Government. They want information and are constantly liable to be misled.”8

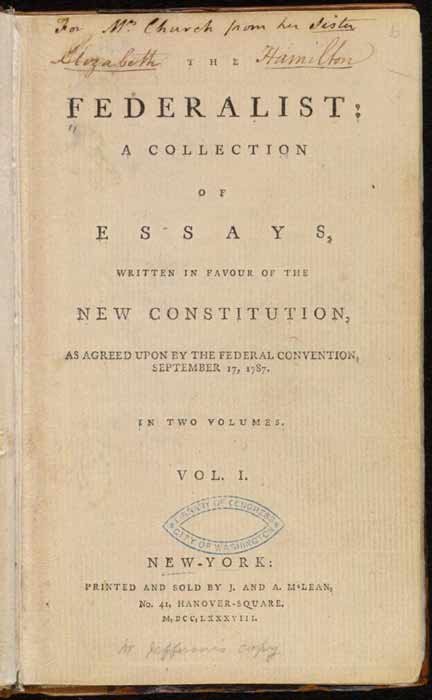

Title page of The Federalist (1788). Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

After the Convention, some defenders of the Constitution called for “a Government administered by the better sort of people.”9 Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison wrote a series of essays called “The Federalist” that defended many of these proposed limitations on the power of ordinary people. They wrote that the Senate was designed to protect the people from “their own temporary errors and delusions.” And they defended the Electoral College for allowing gentlemen with “information and discernment” to choose the president.10 Some of the Constitution’s principal authors believed it could save the republic by limiting the damage that an uninformed citizenry could inflict on itself.

Educating the Public

Noah Webster, like many Americans, believed that in a republic, “knowledge should be universally diffused by means of public schools.”11 The stakes were high: “If the common people are ignorant and vicious,” the Pennsylvania physician and politician Benjamin Rush once claimed, “a nation, and above all a republican nation, can never be long free and happy.”12 Following independence, five states incorporated provisions for public education into their constitutions.13 In 1779, Thomas Jefferson proposed a system of public grammar and secondary schools for Virginia, as well as a state university, expecting that education would protect against “degeneracy” and “tyranny.”

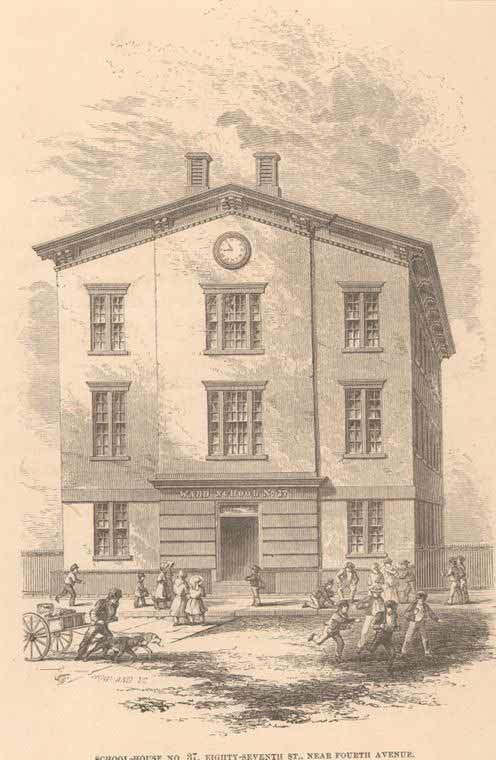

William Howland (engraver), “School-house no. 37,” (n.d.). Courtesy of New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Yet when it came time to fund public schooling, many states balked at the expense.14 After Virginia’s legislature refused to fund Jefferson’s ambitious plan, he complained “the tax which will be paid for this purpose is not more than the thousandth part of what will be paid to kings, priests and nobles who will rise up among us if we leave the people in ignorance.”15

A popular Government, without popular information, or the means of acquiring it, is but a prologue to a Farce or a Tragedy; or perhaps both.16

— James Madison (1822)

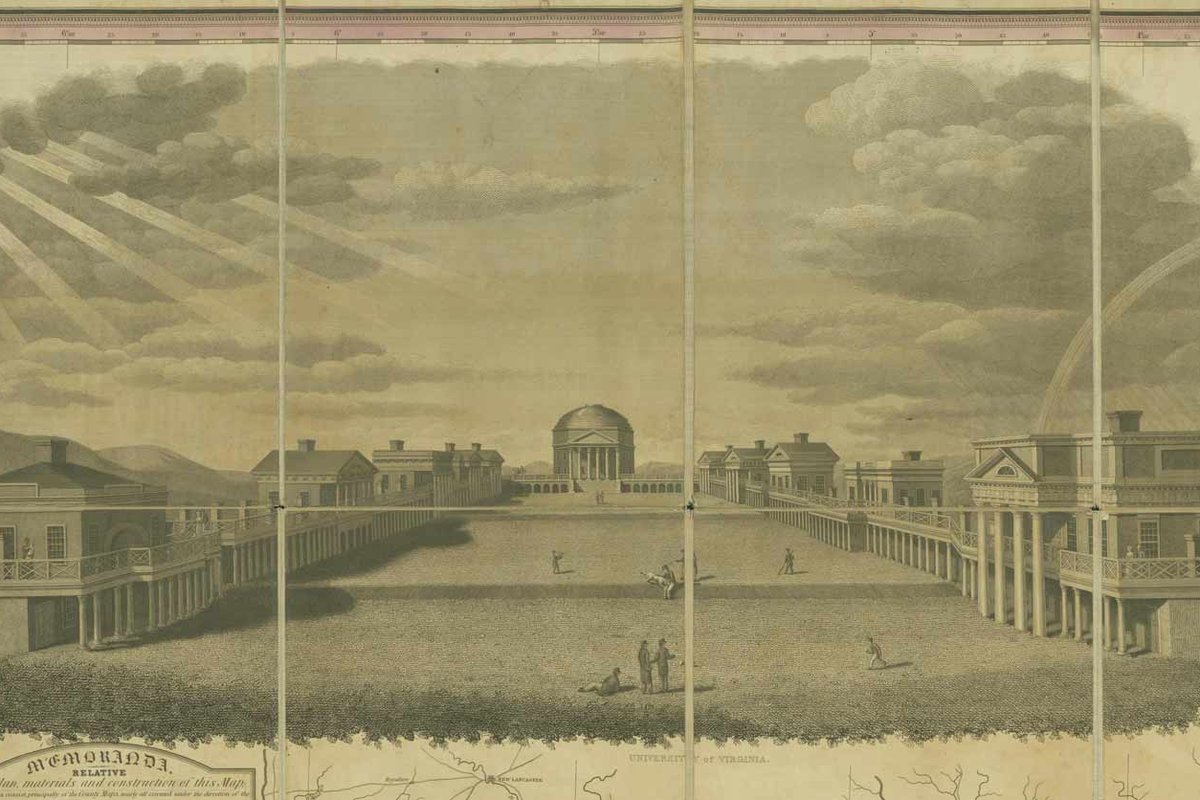

Instead, private academies flourished across much of the United States in the late eighteenth century. Many of these were chartered and at least partially funded by states, sometimes through measures like lotteries or land grants. Geared toward elites, these academies generated a backlash that drove many states to gradually expand public schooling throughout the nineteenth century.17 Eventually, part of Jefferson’s vision for public education came to fruition in 1819 when the University of Virginia was chartered. He listed among the purposes of the new institution, “To instruct the mass of our citizens in these their rights, interests & duties as men and citizens.”18

Republican Wives and Mothers

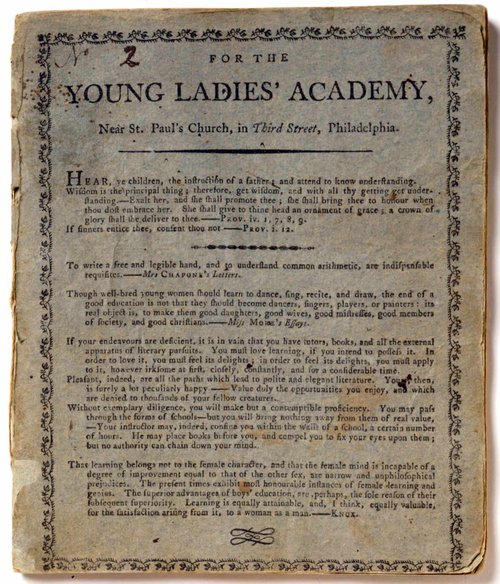

It was unusual to educate women in colonial America. As Abigail Adams once told her husband John, “You need not be told how much female Education is neglected, nor how fashionable it has been to ridicule Female learning.”19 But following independence, some Americans began to see an important role for wives and mothers in cultivating the civic virtue of their husbands and sons.20 In a speech to the Board of Visitors of the Young Ladies’ Academy of Philadelphia, Benjamin Rush argued that female education was an essential part of the “the general diffusion of knowledge among the citizens of our republics.”21

[Benjamin Rush], “For the Young Ladies' Academy” (1787). Courtesy of the Library Company of Philadelphia.

In the first half century of the American republic, more than two hundred academies for women opened.22 Many taught subjects with no practical benefit to household management, such as history, geography, and languages.23 While early academies primarily educated women from elite or middling backgrounds, female education gradually expanded in scope. By the middle of the nineteenth century, literacy rates among American men and women were about equal for the first time.24

Communications

The size of the new United States raised questions. How could citizens be informed about events that occurred hundreds of miles away? Some hoped that constitutional protections of free speech and a free press would promote a robust internal exchange of information and ideas.25 But eighteenth-century communications were slow and unreliable, creating a need for improved infrastructure. As James Madison explained in 1791, “Whatever facilitates a general intercourse of sentiments, as good roads, domestic commerce, a free press, and particularly a circulation of newspapers through the entire body of the people . . . is equivalent to a contraction of territorial limits, and is favorable to liberty.”

The Constitution granted Congress power to “establish Post Offices and post Roads.” In 1792, Congress passed the Postal Act, which led to a massive expansion of communications infrastructure and postal service beyond the Atlantic seaboard.26 Americans soon demanded postal routes, complaining that without it, they were “kept in ignorance,” and “know not any thing which concerns us.”27 The Postal Service quickly became one of the most important institutions in American life, reaching the American population far more deeply than European counterparts. It was the single largest organization in the nation, employing more than two-thirds of the federal civilian workforce, through most of the nineteenth century.28

The 1792 law also set very low rates for sending newspapers through the mail, allowing news to be distributed more effectively to rural customers. This helped to spark an explosion of the newspaper press in the late eighteenth century.29 But for many Americans, newspapers remained a mixed blessing. Yearly subscriptions remained quite expensive until the mid-nineteenth century. Moreover, it wasn’t until the turn of the twentieth century that newspapers began to adopt journalistic standards. Many early American newspapers were just as likely to misinform their readers as inform them.30

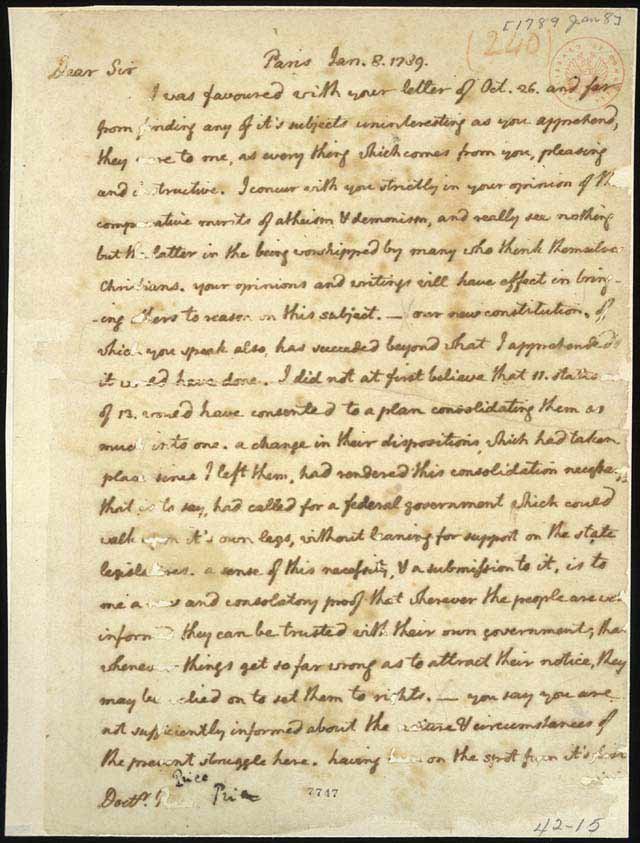

Thomas Jefferson writes, in this 1789 letter written from Paris, that “whenever the people are well-informed, they can be trusted with their own government.” Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Freedom’s Fine Print

At the birth of the United States, the first generation of Americans were asking many questions that continue to occupy us today. Are ordinary people or educated experts better judges of policy? How can a republic avoid being misled by misguided popular passions? How can government promote the spread of useful knowledge?

The Founding generation’s experience offers no clear answers to these questions. But their numerous experiments suggest the urgency of asking them, again and again.

Watch The Video

From the beginning, the Founding generation worried that a republic couldn’t function if its voters and decision-makers were misinformed. In this video, learn about the ways this issue was addressed in the past and ask yourself this question - how informed are you?

Civics

Being a citizen of the United States in the twenty-first century means reckoning with the decisions made in the late eighteenth century. Learn more about the origins of American self-government.

Test Your Knowledge

Sources

Cover image credit: Benjamin Tanner, design of the University of Virginia (1826). Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

- On disparities in access to information in early America, see Richard D. Brown, Knowledge is Power: The Diffusion of Information in Early America, 1700–1865 (Oxford University Press, 1989).

- William Waller Hening, ed., The Statutes at Large … of Virginia (New York, 1810–32): 2:517. See also Bernard de Mandeville’s comment that the welfare of a kingdom required “that the Knowledge of the Working Poor should be confin’d within the Verge of their Occupations, and never extended . . . beyond what relates to their Calling.” Bernard de Mandeville, The Fable of the Bees: Or, Private Vices, Publick Benefits (J. Tonson: 1724), 328, link.

- Brown, Strength of a People, 30.

- Richard D. Brown, The Strength of a People: The Idea of an Informed Citizenry in America, 1650–1870 (Omohundro Institute, 1996), 36–37.

- Brown, Strength of a People, 10, 78; Jack N. Rakove, Original Meanings: Politics and Ideas in the Making of the Constitution (Vintage Books, 1996), 134; James Kloppenberg, Toward Democracy: The Struggle for Self-Rule in European and American Thought (Oxford University Press, 2016), 35–36.

- “To Thomas Jefferson from Edward Carrington, 9 June 1787,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-11-02-0386.

- E. H. Scott, ed., Journal of the Constitutional Convention, Kept by James Madison (Scott, Foresman, and Company, 1893), 368, link.

- Max Farrand, ed., The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787 (Yale University Press, 1967), 1:48.

- “For the Daily Advertiser,” New York Daily Advertiser, Feb, 19, 1788, p. 2.

- [James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay], The Federalist: A Collection of Essays Written in Favour of the New Constitution (J. and A. McLean, 1788), 2:194, 165, 227.

- Noah Webster, “On the Education of Youth in America,” in A Collection of Essays (I. Thomas and E. T. Andrews, 1791), 25, link.

- “To the Citizens of Philadelphia: A Plan for Free Schools,” in Letters of Benjamin Rush (Princeton University Press, 1951), 1:413.

- Boonshoft, Aristocratic Education and the Making of the American Republic, 2.

- Boonshoft, Aristocratic Education and the Making of the American Republic, 2.

- “From Thomas Jefferson to George Wythe, 13 August 1786,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-10-02-0162.

- “From James Madison to William T. Barry, 4 August 1822,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/04-02-02-0480.

- Mark Boonshoft, Aristocratic Education and the Making of the American Republic (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2020), p. 4–5, 122–29, 148–80.

- On Jefferson and the University of Virginia, see Alan Taylor, Thomas Jefferson’s Education (W. W. Norton, 2019), esp. ch. 7.

- “Abigail Adams to John Adams, 30 June 1778,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/04-03-02-0045.

- Brown, Strength of a People, 73.

- Benjamin Rush, Thoughts upon female education, accomodated to the present state of society, manners, and government, in the United States of America (Philadelphia, 1787), 25.

- Boonshoft, Aristocratic Education and the Making of the American Republic, 89.

- Linda K. Kerber, Women of the Republic: Intellect and Ideology in Revolutionary America (Omohundro Institute, 1980), 210.

- Kerber, Women of the Republic, 193.

- Brown, Strength of a People, 74, 83, 86.

- Richard John has shown that the mechanism for the expansion of the postal service was the decision to give Congress, rather than the executive, control of the creation of new postal routes. Richard John, Spreading the News: The American Postal System from Franklin to Morse (Harvard University Press, 1998), 47.

- “To Judge Waties,” State Gazette of South-Carolina, July 1, 1793, p. 1. Quoted in John, Spreading the News, 50.

- John, Spreading the News, 3–6.

- In 1780, approximately 38 newspapers were published. By 1800, that number rose to approximately 260. Harry B. Weiss, A Graphic Summary of the Growth of Newspapers in New York and Other States, 1704–1820 (New York, 1948), n.p.

- See for example Robert G. Parkinson, The Common Cause: Creating Race and Nation in the American Revolution (Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, 2016); Gregory Evans Dowd, Groundless: Rumors, Legends, and Hoaxes on the Early American Frontier (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2015).