Women of the American Revolution

On This page

Introduction

The American Revolution transformed women’s lives. The domestic domain, once seen as divorced from politics, suddenly became political.1 Women’s choices, including what they bought and who they married, carried new political weight. For enslaved women, the upheaval created new opportunities for freedom.

Catherine Rathell wondered if she should leave Virginia since she could not import the goods she needed for her business. Mary Halstead, an enslaved woman, faced the decision of whether to run for freedom, knowing that success meant an unknown future and failure meant severe punishment. As the widowed manager of a plantation, Mary Willing Byrd had to navigate how much to concede when British soldiers landed on her property.

What choices would women make when faced with monument decisions in extraordinary times? What consequences would those decisions bring?

Her Story: Women in Colonial Virginia

This Trend & Tradition article explores women’s lives in colonial America, including how they navigated legal and social constraints.

The Eve of Revolution

Business-Owners and Non-importation:

Catherine Rathell

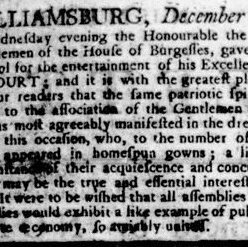

In eighteenth-century Virginia, women owned and operated business of all kinds, from printing presses to taverns. Their livelihoods became entangled in revolutionary politics with the rise of non-importation agreements—pledges to stop importing and purchasing British goods to pressure Parliament to repeal unpopular taxes and policies. Signers of these agreements promised not to import goods from Great Britain. At the same time, consumers were urged not to purchase imported goods in colonial stores.2

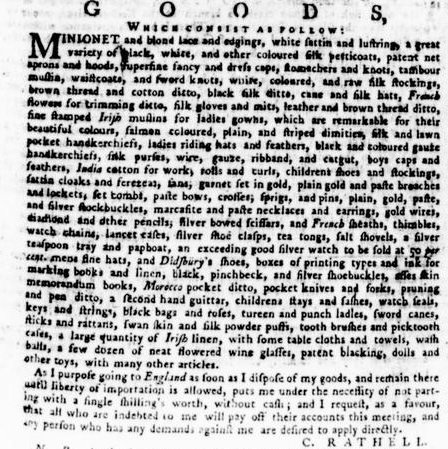

These agreements directly affected female business owners like milliner Catherine Rathell. Rathell came from Britain to Virginia in the 1760s and started her business in the millinery trade.3 She sold fashionable goods imported from Great Britain in her store, including handkerchiefs, fans, and shoe buckles.4 When Virginia’s merchants halted British imports in 1774, Rathell faced a crisis. How could she sustain her business without imported goods? Ultimately she chose to return to England, planning to stay “until liberty of importation is allowed.”5 Just miles from the English shore, the ship she was on got caught in a hurricane and she perished in a shipwreck.6 Though the end of her story was atypical, she was just one of the many colonial women whose business was affected by revolutionary politics.

Dunmore’s Proclamation: Mary Halstead

The American Revolution transformed enslaved women’s lives, opening new opportunities for freedom. In November 1775, Virginia’s royal governor Lord Dunmore issued a proclamation that would change the course of thousands of lives. Dunmore’s Proclamation offered freedom to “indentured Servants, Negroes, or others, (appertaining to Rebels,)” who were "able and willing to bear Arms” and serve in “his Majesty’s troops.”8

While the wording of the proclamation was aimed at men, about a third of the enslaved people who fled to the British for their freedom and were women and children.9 Women often fled with their children. Mary Halstead, who was enslaved in Hampton, Virginia, by Francis Rice, escaped in Spring 1776 with her three-and-a-half-year-old daughter Phillis. The historical record is silent on how they survived the war, but in 1783 they were in New York, getting onto a British ship which took them to Nova Scotia to establish their lives as free people.10

Escaping to Freedom

Learn more about enslaved women who escaped to the British during the American Revolution and what sources reveal, and don’t reveal, about their experiences.

Women & the War

The Home Front: Mary Willing Byrd

While women’s actions became political before the war, the war itself upended their lives. Unable or unwilling to stay in communities ripped apart by political difference, some Loyalists left. Virginia’s Attorney General John Randolph fled with his wife, Ariana, and two daughters, Ariana and Susannah.11 Women who remained at home while their husbands governed or went to war were left to manage their households in a time of economic depression and irregular access to basic necessities.12 They gained new skills and insights as they navigated their family’s business affairs. Some came to value their newfound abilities.13 Massachusetts resident Lucy Knox wrote her husband, General Henry Knox, “I hope you will not consider yourself as commander in chief of your own house — but be convinced… that there is such a thing as equal command.”14

Mary Willing Byrd was a widow whose husband had died in 1777. She took on the tasks of executing his will and raising their children while also managing plantations at Westover and Buckland, Virginia. Meanwhile, the war raged on. In 1781, Benedict Arnold brought an invasion force literally to Mary’s doorstep. Disembarking at Westover plantation, she had no choice but to allow them use of the property. After they left, she communicated with Arnold in order to seek the return of some property, including enslaved people. When the American forces found out about their communications, they searched her home for evidence of spying and put her under house arrest. She was investigated for treason, but never officially tried.15

Women and the Army

Women provided invaluable support to the British and American military as nurses, laundresses, and cooks. In some cases, they were spies and even soldiers.

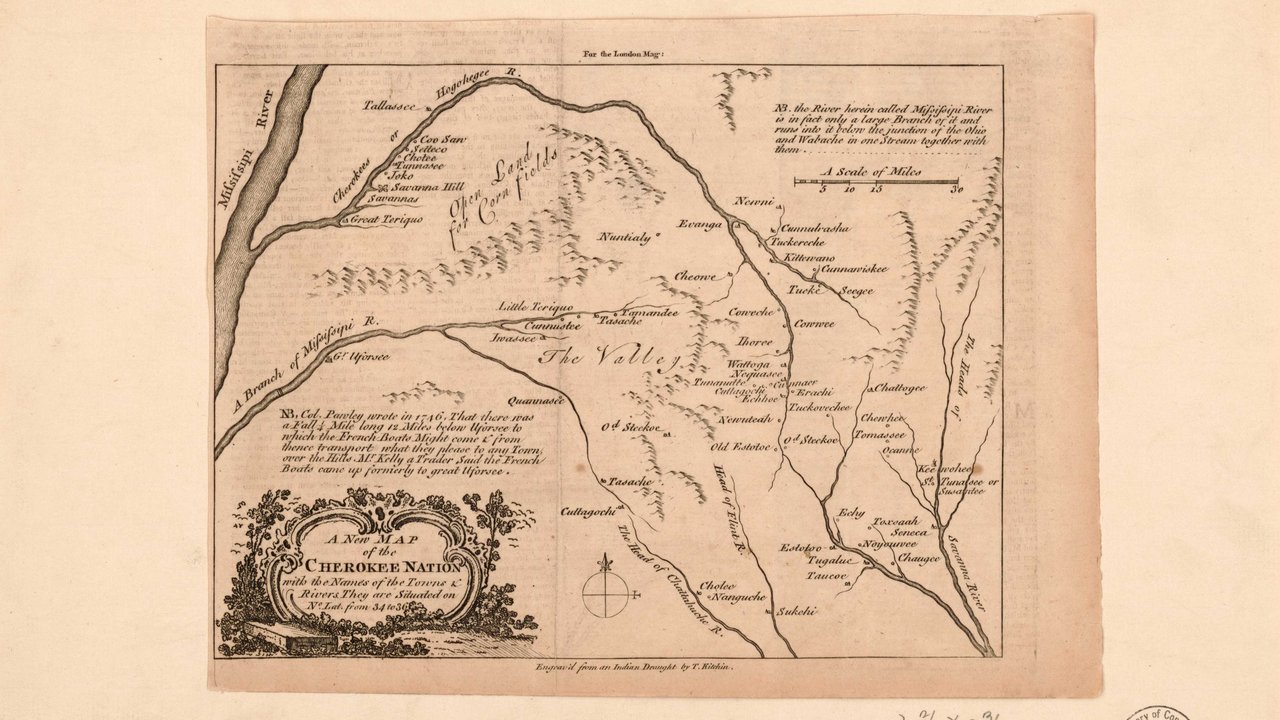

Nanyehi (Nancy Ward): A Beloved Woman of Chota

Learn more about the Cherokee leader who worked for peace during the American Revolution.

Resources

Additional Resources

Learn even more about women by exploring these resources from both our museum and other trusted institutions.

Sources

- Mary Beth Norton, Liberty's Daughters: The Revolutionary Experience of American Women, 1750-1800 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1980), 155-156.

- Norton, Liberty's Daughters, 157-163; James R. Fichter, “Collecting Debts: Virginia Merchants, the Continental Association, and the Meetings of November 1774,” Virginia Magazine of History & Biography 130, no. 3 (2022): 172-217.

- Virginia Gazette (Purdie & Dixon), April 18, 1766; Kaylan M. Stevenson, “’Until Liberty of Importation Is Allowed: Milliners and Mantuamakers in the Chesapeake on the Eve of Revolution” in Barbara Oberg, ed., Women in the American Revolution: Gender, Politics, and the Domestic World (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2019), 39.

- Virginia Gazette (Purdie & Dixon), April 18, 1766; Eleanor Kelley Cabell, “Women Merchants and Milliners in Eighteenth Century Williamsburg,” Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1988, https://research.colonialwilliamsburg.org/DigitalLibrary/view/index.cfm?doc=ResearchReports%5CRR0192.xml.

- Virginia Gazette (Pinkney), April 20, 1775.

- London Evening-Post, October 28-31, 1775.

- Robert Carter to William Taylor, Feb. 21, 1775, Letterbook II, 189, Robert Carter Letter Books and Day Books, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University. Quoted in Norton, Liberty's Daughters, 164.

- Virginia Gazette (Purdie), November 24, 1775, link.

- Benjamin Quarles, The Negro in the American Revolution (Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1961), 171-2.

- The Book of Negroes, Guy Carleton, 1st Baron Dorchester: Papers, The National Archives, Kew (PRO 30/55/100) 10427, 148-149, https://archives.novascotia.ca/africanns/book-of-negroes/page/?ID=85.

- Virginia Gazette (Dixon and Hunter), September 9, 1775. Four years later, Randolph wrote to Thomas Jefferson about his experience as a Loyalists in Williamsburg, including how people treated his wife and daughters, “But, the unmanly and illiberal Treatment, which the more delicate Part of my Family met with, I confess, fill’d me with the highest Resentment.” John Randolph to Thomas Jefferson, October 25, 1779, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-03-02-0137.

- Carol Berkin, Revolutionary Mothers: Women in the Struggle for America's Independence (Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), 24-35.

- Norton, Liberty's Daughters, 215-225.

- Lucy Knox to Henry Knox, August 23, 1777, Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, https://www.gilderlehrman.org/sites/default/files/02437.00638_OS.docx_.pdf.

- Ami Pflugrad-Jackisch, “’What Am I but an American?’: Mary Willing Byrd and Westover Plantation during the American Revolution,” in Barbara Oberg, ed., Women in the American Revolution, 176-185. Some of the people enslaved at Westover used the British presence to their advantage and ran. One woman, Fanny Harris, appears in the Book of Negroes in 1783, https://blackloyalist.com/cdc/documents/official/black_loyalist_directory_book_two.htm.

- Berkin, Revolutionary Mothers, 51-53.

- Sarah Benjamin’s Eyewitness Account of the Surrender at Yorktown, November 20, 1837, National Archives, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/1636083?objectPanel=transcription.

- Judith Jackson to Carleton, “Judith Jackson to Carleton. New York. Petition. Discusses her previous situation in service and [. . .] ,” September 18, 1783, 30/55/81/95/9158, Guy Carleton, 1st Baron Dorchester Papers, PRO, TNA. Quoted in Kacy Dowd Tillman, “The Limits and Liberty of Loyalty: Black Loyalism in the Book of Negroes,” Early American Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal 23, no. 1 (Winter 2025): 48.

- Norton, Liberty's Daughters, 174-175.

- Sandra Gioia Treadway, “Anna Maria Lane: An Uncommon Soldier of the American Revolution,” Virginia Cavalcade 37, no. 3 (1988): 134–143; “Anna Maria Lane, Commendation and Pension Award from William H. Cabell, 1808,” Document Bank of Virginia, accessed March 18, 2025, https://edu.lva.virginia.gov/dbva/items/show/255.

- Ben Harris McClary, “Nancy Ward: The Last Beloved Woman of the Cherokees,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 21 (December 1962): 352-364.

- Norton, Liberty's Daughters, 174-175.