Escaping to Freedom

Stories of Enslaved Women in Revolutionary Virginia

Primary source documents provide crucial insights into how enslaved women in Virginia experienced the American Revolution. Many of these records offer only fragmentary details about their lives—names, ages, enslavers, locations. These sparse entries can be both revealing and limiting. Enslaved women navigated extraordinarily difficult and often perilous choices during the Revolution. While historical records sometimes document the decisions they made, they rarely capture the personal motivations, emotions, or consequences of these choices. They rarely tell us what it meant to leave or to be left behind.

Yet these lists serve as testimony. They confirm women’s presence and agency, however faintly recorded. A name, whether scribbled or printed, represents an individual who lived, persevered, and made choices within the upheaval of war. They offer glimpses into the experiences of these women, illuminating how they engaged with and were affected by the revolution. Though their inner thoughts remain beyond the reach of the historical record, their actions and the traces they left behind speak to their lived realities.

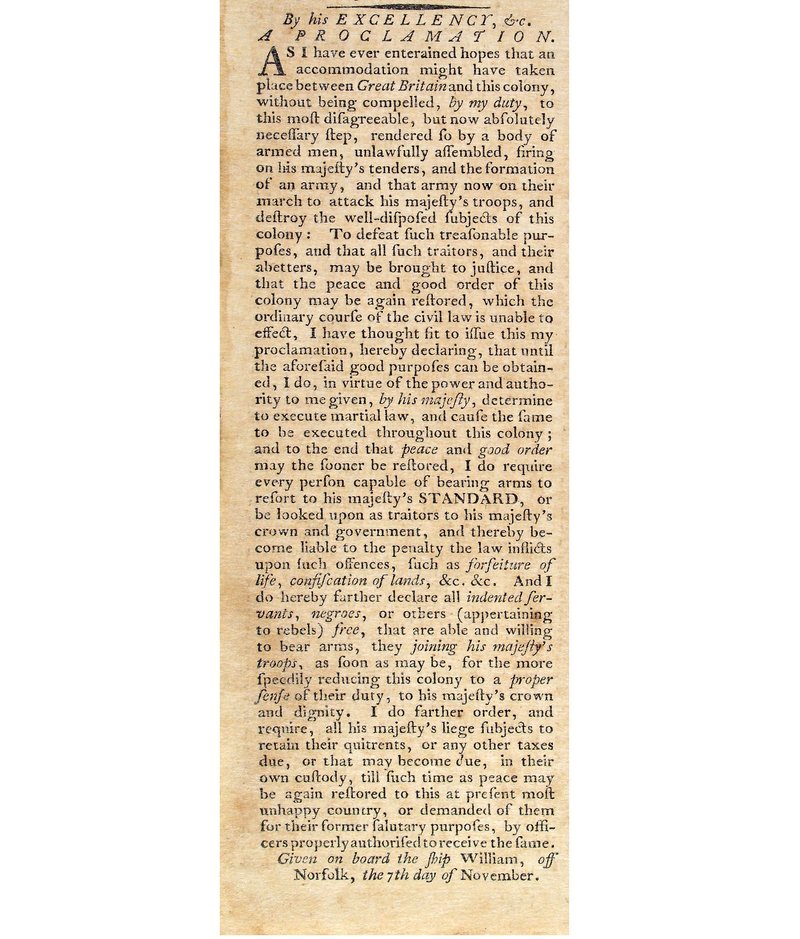

Dunmore’s Proclamation

The document that most affected enslaved women’s experiences in Virginia during the American Revolution was not created with them in mind. In November of 1775, the royal governor of Virginia, Lord Dunmore, issued a proclamation offering freedom to “indented servants, negroes, or others, (appertaining to Rebels)” in Virginia who were "able and willing to bear arms” in service of the British Crown.1

For enslaved men and women, this often presented an agonizing choice. Fleeing could mean leaving behind family, community, and everything familiar. A letter published alongside Dunmore’s Proclamation in the Virginia Gazette sought to deter escape, warning that Dunmore might not take in women and children given his Proclamation’s focus on the ability to bear arms. Should men run to Dunmore, the letter warned, they would be leaving behind women and children to face the vengeance of their enslavers.2 Rumors spread that Dunmore had no intention of keeping his promise, and those who reached him would be sold to the West Indies.3 Meanwhile, rebels reminded enslaved people that the punishment for insurrection was death.4

At every turn there was uncertainty and danger. But if they ran—and if Dunmore kept his promise—there was the possibility of freedom.

John Willoughby’s Petition

Virginia Gazette (Dixon and Hunter), August 31, 1776.

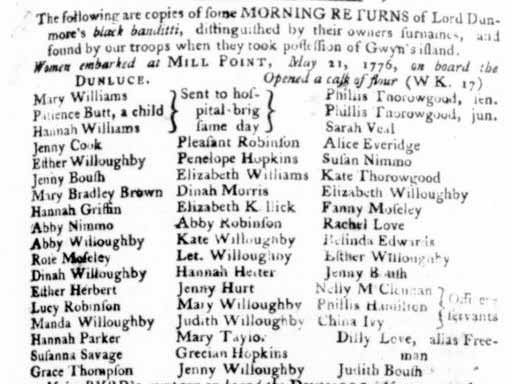

Although Dunmore’s Proclamation explicitly targeted men capable of military service, enslaved women also seized the opportunity.5 Between 1,000 and 1,500 enslaved men, women, and children sought his protection.6 They joined his “Floating Town” of about 200 ships in Norfolk, Virginia, before relocating to his new base at Gwynn’s Island. Isolated and overcrowded, the camp was ravaged by smallpox. Conditions were bleak. In July of 1776, facing defeat and unable to reclaim Virginia, Dunmore’s camp made a hasty retreat to the British stronghold of New York City.7

Rebels swept into the camp, horrified to find the dying and dead left behind.8 Sifting through papers left behind in the hasty departure, they found a list of formerly enslaved individuals who had reached his camp, including the names of 49 women.9 Eleven shared the last name Willoughby. These names are clues—fragments that, when traced, reveal more.

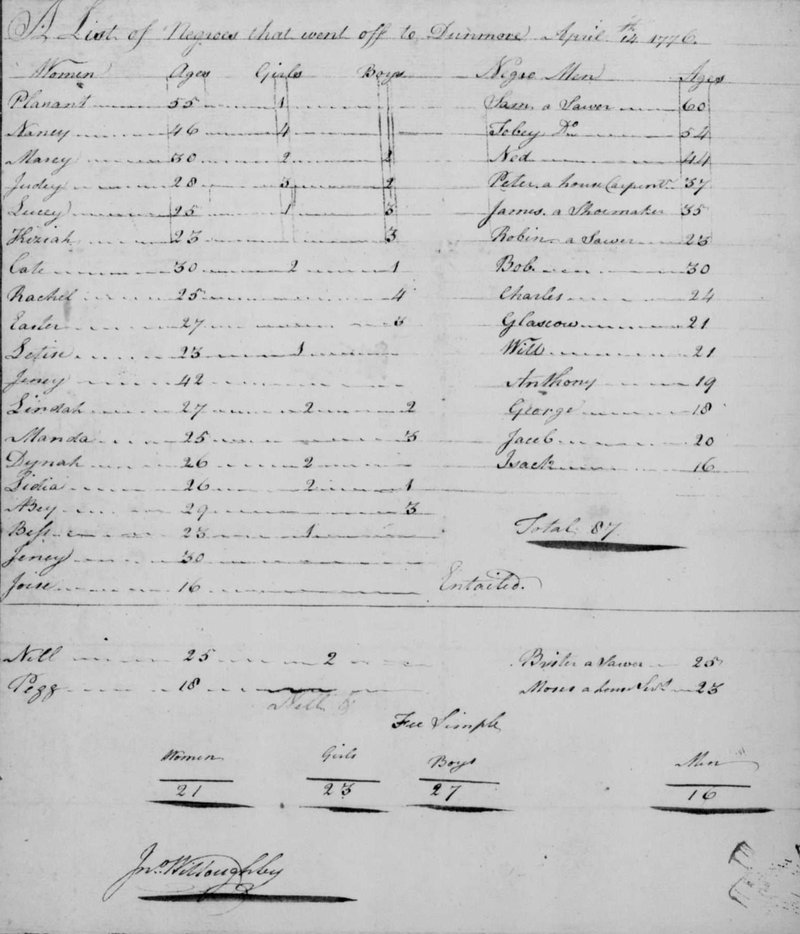

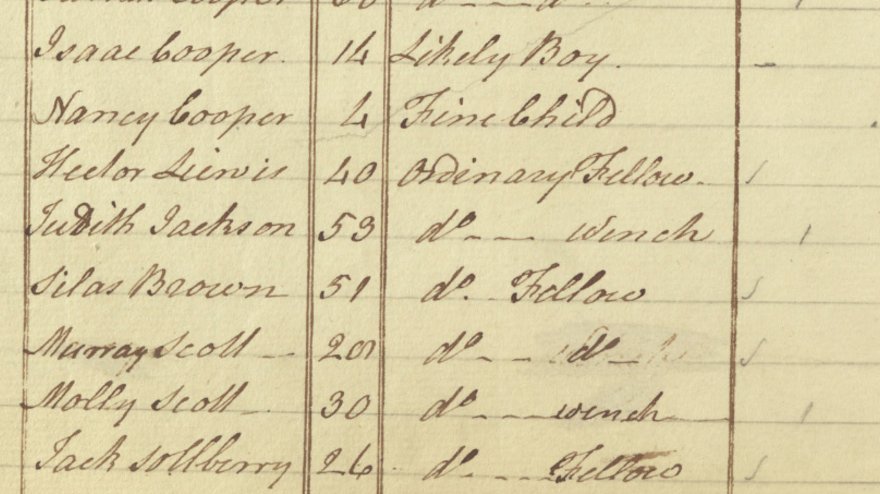

John Willoughby Jr., a Norfolk plantation owner, reported that on April 14, 1776, a month before Dunmore left for Gwynn’s Island, about 87 of the people he enslaved had escaped.10 From this report, filed as a petition to the Virginia government for compensation, we learn more about some of the women who were with Dunmore. Marey was 30 years old. Almost all brought children with them. More women escaped than men—21 women to 16 men.11

Petition of John Willoughby Jr. To the Virginia House of Delegates, June 3, 1777. Library of Virginia.

Yet the petition also reflects how Willoughby and other enslavers viewed the people they claimed as property. Enslaved families often fled together—during the revolution, nearly half of those who ran away did so in groups, often with spouses and children.12 But Willoughby’s record does not list family groups, instead listing men and women separately, and listing children solely under their mothers. Rather than reflecting the relationships between enslaved men and women, the document reinforced how enslavers categorized their lives.

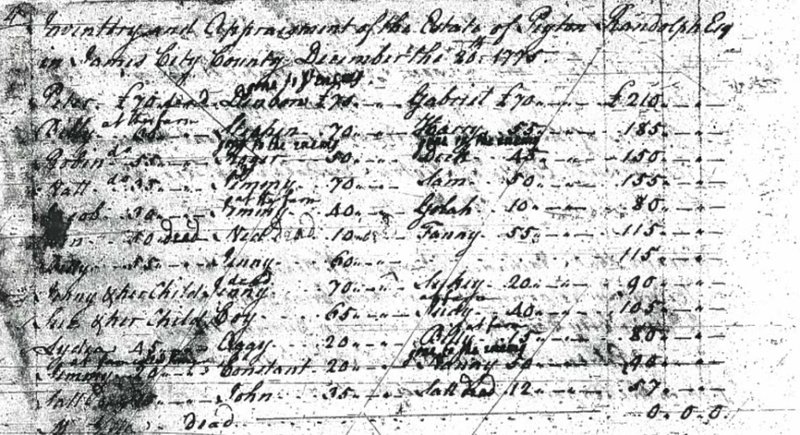

The Peyton Randolph Inventory

Successfully escaping slavery was often a matter of timing. Knowing the best moment to flee could be the difference between making it to freedom and being recaptured. As the war raged on, properly timing escape took patience, skill, and knowledge. Enslaved people had to gather information about and follow the shifting terrain of military presence. As the conflict moved away from Tidewater Virginia, many enslaved people waited for the right moment to flee.13

That moment came when the war returned to Tidewater Virginia in 1781. Among those who ran to British forces were eight individuals from the Randolph property, including four women—Nanny, Eve, Aggy, and Lucy. Peyton Randolph had been a prominent political leader. When he died in 1775, an inventory was created of his property, including the people he enslaved. This document records little about these women beyond their names and assigned monetary value. It does not tell us who these women’s friends were, their favorite time of day, or what made them decide to flee. A single note by each of their names, likely added in 1781, simply states that they had “gone to the enemy.”14

Estate of Peyton Randolph, 1776. Library of Congress.

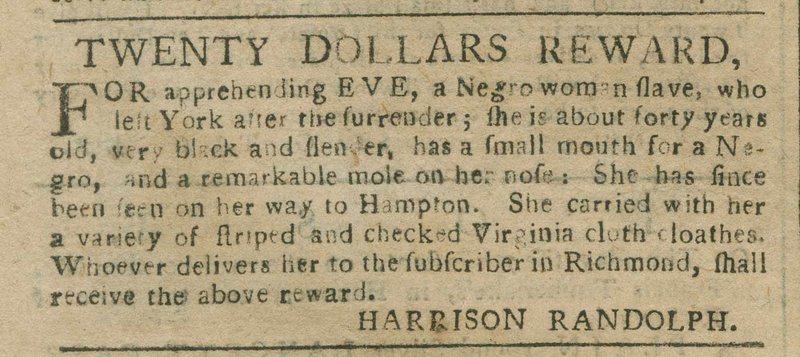

Eve was highly skilled, and possibly a personal maid. She was among the highest-valued individuals on the Randolph estate, listed at £100. A year after her escape, Randolph’s nephew placed a runaway advertisement offering a reward for her return. From this, we learn that she was about 40 years old, had a mole on her nose, “carried with her a variety of striped and checked Virginia cloth clothes,” and that she was last seen heading toward Hampton. The Randolphs soon recaptured Eve. A codicil to the will of Betty Randolph (the widow of Peyton Randolph) dated July 20, 1782, notes that she had sold Eve due to her “bad behavior,” likely a reference to her recent escape.15 The rest of her story remains unknown.

Virginia Gazette, February 2, 1782. Swem Library, College of William and Mary.

The “Book of Negroes”

Those who fled to the British during the American Revolution saw their fates tied to the shifting tides of war. After the battle of Yorktown, many ended up in the last British stronghold of New York City.16 From there, the British administration evacuated thousands of Loyalists, including 3,000 self-liberated people. Their names were recorded in the “Book of Negroes,” the most comprehensive list of the men and women who self-liberated during the American Revolution. This bureaucratic record provides invaluable details about Black women‘s lives—their names, ages, family relationships, former enslavers and locations, the timing of their escape, and their destinations.17

Judith Jackson

Judith Jackson ran from her enslaver, John Clain, in Norfolk, Virginia, to the British in 1779. Read about her journey from Norfolk to Nova Scotia.

Book of Negroes, National Archives.

Only five women formerly enslaved by John Willoughby appear in the Book of Negroes: Abby Milligan (age 30), Mary Perth (43), Zilpah Cevils (15), Hannah Cevils (10), and Patience Freeman (18). Zilpah, Hannah, and Patience had all been children when their mothers picked them up and carried them to freedom.18 What had happened to the other women who fled to Dunmore seven years earlier? Like many who sought refuge with the British, they might have succumbed to disease. Others might have slipped away over the years, forging new lives in American cities or in maroon communities.19

Mary Perth, with her husband Caesar and daughter Patience, boarded a ship for Nova Scotia. Nearly a decade later, they left for Sierra Leone, a colony in Africa established for free Black Loyalists. Mary went to England in 1799 and then returned to Sierra Leone, where she died in 1813, at around 69 years old. Her decision to seek freedom in 1776 ultimately took her across the world, and she influenced countless lives through her role as a preacher and educator.20

These records remain incomplete, offering only fragments of women’s lives. Yet they are still a starting point, an invitation to uncover more. At the very least, they preserve something vital: the names of women who dared to create a future beyond bondage.

Women and the American Revolution

Women’s lives were transformed by the American Revolution. Discover how their domestic roles became political and expanded during the war.

Sources

- Virginia Gazette (Purdie), November 24, 1775, link.

- Virginia Gazette (Purdie), November 24, 1775, https://research.colonialwilliamsburg.org/DigitalLibrary/va-gazettes/VGSinglePage.cfm?issueIDNo=75.P.83&page=2&res=LO.

- Edmund Pendleton to Thomas Jefferson, November 16, 1775, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-01-02-0135.

- The Proceedings of the Convention of Delegates for the Counties and Corporations in the Colony of Virginia (Ritchie, Trueheart & Du-val, 1816), 66, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.35112105042149&seq=94&q1=.

- James Corbett David, Dunmore’s New World: The Extraordinary Life of a Royal Governor in Revolutionary America--with Jacobites, Counterfeiters, Land Schemes, Shipwrecks, Scalping, Indian Politics, Runaway Slaves, and Two Illegal Royal Weddings (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2013), 107.

- David, Dunmore’s New World, 107; Cassandra Pybus, “Jefferson’s Faulty Math: The Question of Slave Defections in the American,” The William and Mary Quarterly 62, no. 2 (April 2005), 250.

- David, Dunmore’s New World, 121-125. “Floating Town”: Captain Andrew Snape Hamon to Vice Admiral Molyneux Shuldham, Naval Documents of the American Revolution 7:319, https://archive.org/details/navaldocumentsof07unit/page/318/mode/2up?q=.

- Virginia Gazette (Purdie, July 19, 1776.

- Virginia Gazette (Dixon & Hunter), August 31, 1776.

- Petition of John Willoughby Jr., 3 June 1777, Norfolk County, Virginia, Legislative Petitions of the General Assembly, 1776-1865, Accession Number 36121, Box 181, Folder 4 Library of Virginia (link).

- Ibid.

- Karen Cook Bell, Running From Bondage: Enslaved Women and Their Remarkable Fight for Freedom in Revolutionary America (Cambridge University Press, 2021), 9, 84.

- Bell, Running From Bondage, 82-83.

- R. Townsend, “Peyton Randolph Historical Report, Block 28 Building 6 Lot 207 & 237,” Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1967, https://research.colonialwilliamsburg.org/DigitalLibrary/view/index.cfm?doc=ResearchReports\RR1537.xml; “Enslaving Virginia,” Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1998, https://cwfpublications.omeka.net/items/show/170, 635-647.

- Virginia Gazette or American Advertiser (Hayes), February 2, 1782, http://www2.vcdh.virginia.edu/gos/search/relatedAd.php?adFile=vg1782.xml&adId=v1782020017. Patricia A. Gibbs, “Peyton Randolph House Historical Report, Block 28 Building 6 Lot 207 & 237,” (1990) Colonial Williamsburg Digital Collections.

- Bell, Running From Bondage, 103.

- Maya Jasanoff, Liberty’s Exiles: American Loyalists in the Revolutionary World (Alfred A. Knopf, 2011), 89; ”Book of Negroes,” Nova Scotia Archives, https://archives.novascotia.ca/africanns/book-of-negroes/.

- Book of Negroes Book 1, part 2, Black Loyalist Directory, https://blackloyalist.com/cdc/documents/official/black_loyalist_directory2.htm.

- Bell, Running from Bondage, 105.

- Bell, Running From Bondage, 103-104; Edward Arnold, ed. Life and Letters of Zachary Macaulay (A. Constable, 1900). Documents show a discrepancy in Perth’s age: Willoughby’s petition claimed she was born in 1753, but according to the Book of Negroes she was born in 1744.