Who Were Williamsburg’s Enslaved Gardeners?

Early Williamsburg’s gardens, some of the finest in the colonies, would not have existed without the skill and labor of enslaved people. Plantation slavery generated the surplus wealth that members of the gentry elite invested into creating elaborate pleasure gardens. Highly skilled enslaved gardeners sculpted landscapes, planted seeds, hauled water, pulled weeds, harvested plants, and learned from the soil.

Enslaved people worked in all kinds of gardens. They cared for gardens surrounding private homes, ranging from small, practical gardens kept by middling families to the renowned pleasure garden owned by John Custis IV. They kept some of the tavern gardens that grew food for the town’s visitors. Enslaved people also maintained the expansive public gardens on the grounds of the Governor’s Palace and the College of William & Mary. Both the knowledge and the spadework of enslaved workers planted the seeds of Williamsburg’s eighteenth-century gardens.

Skilled Tradesmen

Williamsburg’s gardens benefited from their proximity to Virginia’s outlying plantations. The colony’s elite came to the capital to trade plants, tools, and knowledge. Some enslaved people also moved between the plantations and Williamsburg, bringing with them the experience they gained from planting cash crops, growing their own food, and maintaining their enslavers’ pleasure gardens.1 Many enslaved agricultural laborers were acknowledged to be expert horticulturalists. Enslaver Landon Carter’s diary, for example, records many instances of enslaved people informing or correcting him about planting.2

Enslaved Virginians’ Plantation Gardens

Enslaved people on eighteenth-century Virginia plantations grew much of their food in garden plots. What did they eat? What were their gardens like?

Enslaved people who were skilled gardeners were in high demand. Williamsburg’s elite often moved enslaved people around multiple sites or brought skilled gardeners in from surrounding plantations. Records indicate that an enslaved man named James worked as a gardener at the Governor’s Palace gardens from 1765 to 1777. His time there spanned the terms of three governors. His retention indicates that he was highly knowledgeable. During that time, his enslaver Lewis Burwell received £12 per year in exchange for James’s work at the Palace. This was a relatively high payment, further evidence of the demand for his work.3

We can also detect the skill of enslaved gardeners in the landscapes they created. Enslaver and plantation owner John Custis IV, who kept Williamsburg’s most celebrated private garden, relied on enslaved workers to maintain its intricate features, including neatly clipped topiaries and espaliered fruit trees. The enslaved people who worked in these gardens were not simply laborers performing drudgery. “These were not simple, cottage gardens,” according to Jack Gary, Colonial Williamsburg’s Executive Director of Archaeology, “In order to make these elaborate gardens function like they were supposed to, you needed skilled labor.”

Even everyday tasks could require a high degree of skill. One enslaved man named Ellick faced exacting demands for garden maintenance. In 1802, Williamsburg resident Joseph Prentis Sr. wrote to his son to ask him to “Tell Ellick that I expect the Gardens will be in very nice order, the Asparagus Beds . . . done up neatly, and the Walks in Small Garden and in the Yard gravelled. Those in the Yard to be rounding at top, and that in the small Garden perfectly flat, and level, but filled pretty high with gravel.” A few years later, Prentis’s son sold the home with “the Gardner Ellick.” Ellick was the only enslaved person included in the sale, which indicates the value he brought to the property.4

Labor

Virginia settlers rarely cultivated pleasure gardens until the early eighteenth century. This was largely due to a labor shortage in the colony. With crops to raise and mouths to feed, it was unusual for settlers to devote scarce resources to ornamental gardens. But the growth of slave labor in eighteenth-century Virginia made it much cheaper for elites to create fashionable pleasure gardens.5

While enslaved gardeners were skilled workers, their work was also physically demanding. The climate didn’t help. In the hotter and dryer months, especially, enslaved people drew gallon after gallon of water from wells and hauled them to plants. During a drought in 1738, for example, John Custis had three “strong” enslaved men “continually filling large tubs of water” for the plants and creating artificial shade to protect them.6 In the summer heat, this would have been grueling work.

At the Governor’s Palace, enslaved people carved a canal and terraced gardens out of a ravine. They planted intricate symmetrical designs for flowers and greenery. They hauled load after load of soil to build the earthen mount that overlooked the garden.7 Once complete, enslaved labor maintained the Palace gardens. At any given time, several enslaved people worked in the Palace gardens under the supervision of a white gardener.8

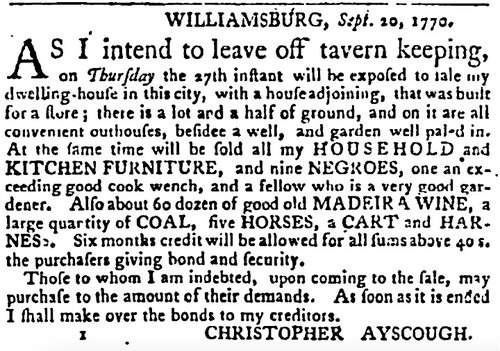

In 1770, Christopher Ayscough advertised the sale of nine enslaved people, including “a fellow who is a very good gardener,” a reference to Lancaster. Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon), Sept. 20, 1770, p. 3.

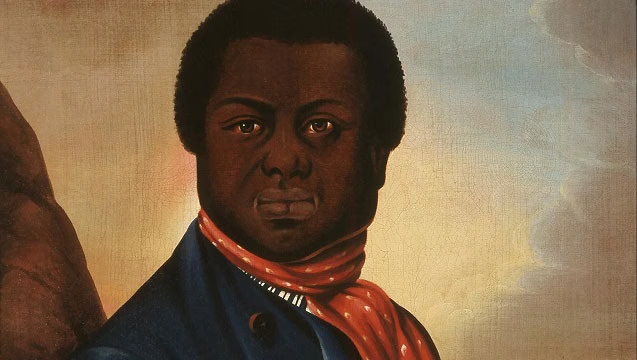

After Governor Francis Fauquier died in 1768, his will lamented that “my situation” as governor had, as he saw it, made practicing enslavement "necessary for me.” Unable to legally emancipate these people himself, he allowed the people he enslaved to choose their next enslaver. An enslaved gardener named Lancaster chose to be purchased by Christopher Ayscough, the Palace’s white gardener. While we don’t know the reasons for Lancaster’s decision, it is likely that he came to know Ayscough by working alongside him in the gardens.9 Since Fauquier’s successor brought his own gardener from England, Ayscough took up a new line of work as a tavernkeeper. But when he shut down his tavern a couple of years later, he offered Lancaster for sale. An advertisement in the Virginia Gazette explained that he was selling his lot, including a “garden well paled [fenced]” and “nine Negroes” including “a fellow who is a very good gardener.” While Fauquier allowed Lancaster to choose his next enslaver in 1768, he was unable to control his fate after that.

Resistance

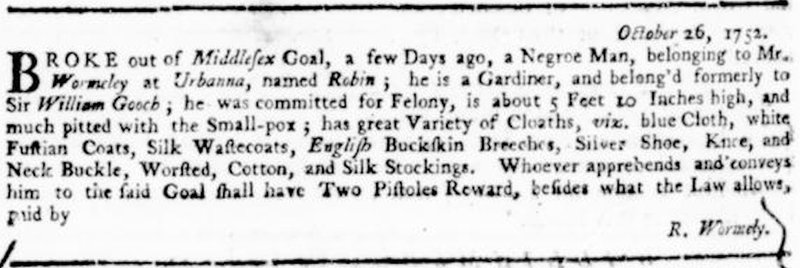

In some cases, our only knowledge about an enslaved gardener comes as a result of their resistance against slavery. Two advertisements in the Virginia Gazette sought the return of enslaved gardeners who had once been owned by Lieutenant Governor William Gooch, and likely worked in the Palace Gardens. In 1752, an advertisement identified a man named Robin as a “Gardiner” who “belong’d formerly to Sir William Gooch.” He had been imprisoned in Middlesex County, not far from Williamsburg, but had escaped.

Virginia Gazette (Hunter), Oct. 27, 1752, p. 2.

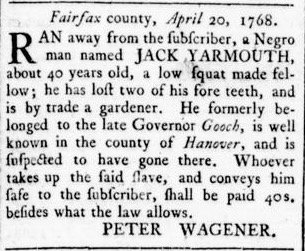

Another enslaved man named Jack Yarmouth escaped from his enslaver, Peter Wagener, in 1768. Wagener’s advertisement described Yarmouth as “by trade a gardener” who “formerly belonged to the late Governor Gooch.” Given that Gooch occupied the Governor’s Palace for more than two decades, Robin and Jack Yarmouth might have known each other.

Virginia Gazette (Rind), May 12, 1768, p. 3.

Virginia Gazette (Purdie), July 10, 1778, p. 3.

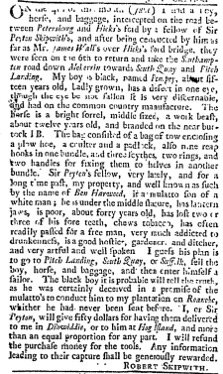

Yet another advertisement contained white enslaver Robert Skipwith’s accusation of theft against the enslaved man Ben Harwood. In 1778, Skipwith claimed that Harwood, who was a “good hostler, gardener, and ditcher,” had stolen a horse, an enslaved boy, and some agricultural tools from him. A month later, another advertisement in the Virginia Gazette suggested that Harwood was claiming to be free and had asked an officer to “enlist him a soldier” during the American Revolutionary War.10

Conclusion

Millions of visitors have enjoyed the restored pleasure gardens of Colonial Williamsburg. These gardens represent the aspirations of an eighteenth-century elite imitating the fashionable gardens of England and continental Europe. But they also represent a workplace—a site where enslaved gardeners skillfully practiced their trade. It was their skill and labor that transformed Williamsburg into one of the foremost centers of ornamental gardening in colonial North America. It is easy to forget these stories amid the beauty of these gardens, but they are essential to this history.

Stories of Black Life

During the 18th century, half of Williamsburg’s population was Black. Discover these American stories of resilience and explore those who lived, loved, and strove to create a better future.

Sources

- Peter Martin, “‘Long and Assiduous Endeavours’: Gardening in Early Eighteenth-Century Virginia,” in Robert P. McCubbin and Peter Martin, eds., British and American Gardens in the Eighteenth Century: Eighteen Illustrated Essays on Garden History (Williamsburg: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1984), 114.

- Philip D. Morgan, Slave Counterpoint: Black Culture in the Eighteenth-Century Chesapeake and Lowcountry (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1998), 192–93.

- Peter E. Martin, “The Governor’s Palace Gardens: ‘lavishing away’ The Colony’s Money,” Colonial Williamsburg Digital Library, 28.

- Joseph Prentis Sr. to Joseph Prentis Jr. Oct. 1802, in “Lots 319-328 (Green Hill) Historical Report,” Colonial Williamsburg Digital Collections, n.p.

- Peter Martin, The Pleasure Gardens of Virginia: From Jamestown to Jefferson (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2001), 14.

- Brothers of the Spade: Correspondence of Peter Collinson, of London, and of John Custis, of Williamsburg, Virginia, 1734-1746 (Barre, Mass.: Barre Gazette, 1957), 55.

- There is no available information about the enslaved people who worked to construct the Palace gardens. The Virginia House of Burgesses authorized Henry Cary, the supervisor for constructing the Palace, to purchase “such and so many slaves, horses, carts and other necessaries” as he “shall think fitt.” William Waller Hening, ed., The statutes at large; being a collection of all the laws of Virginia, from the first session of the legislature, in the year 1619 (Philadelphia: Thomas Desilver, 1823), 3:485, link.

- In 1769, for example, the Palace’s butler recorded payments for the services of four enslaved men, named Bacchus, Will, Jack, and Tom. “Enslaving Virginia,” Colonial Williamsburg research report (1998), p. 587–88.

- For those whom an enslaved person had chosen as their preferred purchaser, Fauquier’s executors offered a twenty-five percent discount on their sale. Lancaster’s assessed value was listed as £70, but he was sold to Ayscough for £52 and 10 shillings—indicating that this discount was included in the purchase price. See “Inventory of Goods and Effects belonging to the Estate of The Honble Francis Fauquier Esquire Deceased taken at Williamsburg Virginia,” Colonial Williamsburg Digital Library, link.

- The original version of the second advertisement has been mutilated but is legible. Virginia Gazette (Purdie), Aug. 21, 1778, p. 3, link.