Black Childhood in 18th-Century America

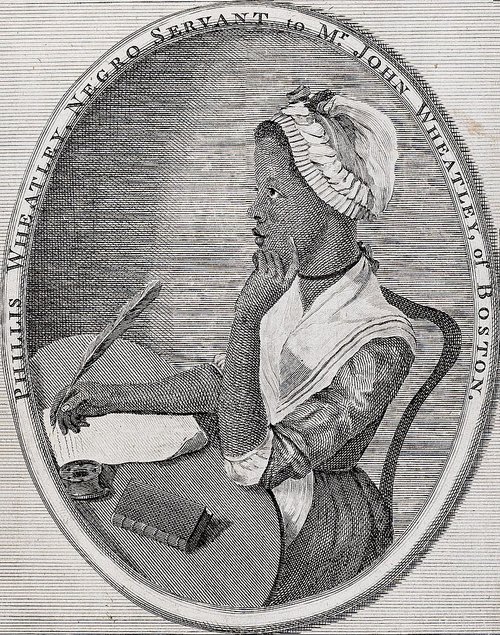

Portrait of Phillis Wheatley, Frontispiece of Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (1773).

A young girl, no more than seven or eight years old, stepped off a ship and into a new world. A new continent. A new society. But this was not a moment of discovery and adventure. This girl, likely born in what is now Gambia or Senegal, had just been forced to endure a multi-month trek across the Atlantic Ocean. Captured in West Africa, she was trafficked across the ocean and arrived in Boston on July 11, 1761.1 The name she arrived with is lost to us. The name she soon received, however, became famous in her day and ours.

Phillis Wheatley was given the name of the very ship that had transported her, and many other enslaved people, from one hemisphere to another. Bought by John Wheatley, a wealthy Boston merchant, Phillis would become known as a child prodigy within just a few years. She became one of the most well-known poets of her time, white or Black. Hers is a well-known story. But the stories of America’s many other Black children, free or enslaved, are less known. They experienced a world that devalued them because of their race, and often ignored them because of their age. What Black children experienced can help us understand the trajectory of both the burgeoning colonies-turned-nation and the institution of slavery itself.

Labor and Family

Family life was precarious for enslaved children. Though often separated, families found ways to come together. Children living with one parent might visit another on a neighboring plantation. Some children lived with both parents. In Williamsburg, an urban area, three-quarters of enslaved children lived in households with both an adult man and woman, indicating many lived with both parents.2 Many enslaved children had family beyond blood relatives. Creating families out of non-blood-related people, sometimes referred to as fictive kin, became a defining and enduring feature of Black families, as various members of the community stepped into familial roles.3

Enslavers expected enslaved children to perform labor beginning at young ages. Children took care of younger children, which allowed parents to perform their labor. By the time they became adolescents, enslaved children on plantations were often forced to perform the same tasks as adults, especially in field labor.4

Play for Enslaved Children

Clay marbles excavated from the root cellar of the house of an enslaved family at Carters Grove Plantation.

The 18th century saw the rise of toys and books for children, as parents began to encourage play for childhood growth. A popular children’s book, for example, could be bought with toys for a small additional charge. Enslaved children, however, wouldn’t have had easy access to the growing children’s literature market.5

Even though manufactured toys were out of reach for many, it is possible that some Black children or family members bought toys with money made through extra labor. Moreover, children made their own toys and games. Everyday items could operate as toys, or be used to build them. For example, archaeologists have found marbles in enslaved families’ living quarters. Often, such marbles were made of hardened clay, as that was the cheapest and most accessible material. Unlike some other toys, clay marbles could be made by hand, and likely allowed children to craft their own sets.6

Educating Children

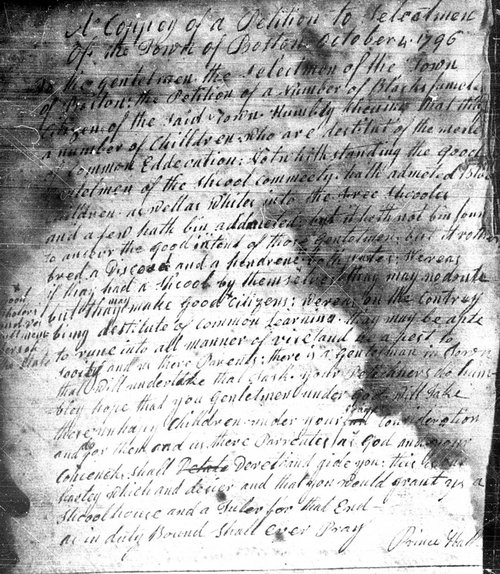

Petition for a School for Black Children in Boston, 1796.

Education was one of the biggest differences between the childhoods of white and Black children during this period. While schooling was not universal during this period, white children enjoyed increased access to it in the North, while the children of wealthy southerners often had private tutors.7 Whether free or enslaved, however, Black children had almost no access to education.

The experiences of someone like Phillis Wheatley were unusual. What Phillis’s education looked like is still a mystery. It’s very possible Phillis was initially taught by the Wheatleys’ daughter, Mary. By the time she was a teenager, though, she was already an adept poet, illustrating a level of education almost unheard of for enslaved children.

Phillis’s education was unusual, but it was perfectly legal to educate enslaved people during this period. In the 19th century, teaching enslaved people would be outlawed in most southern states. But white leaders nonetheless discouraged teaching enslaved children. Enslaver Robert Carter Nicholas pointed out that many white enslavers complained that the most educated “of our Slaves are the most wicked & ungovernable.”8 Literacy could prove especially useful to runaway slaves, who could forge a pass from their enslaver, cloaking their illegal movements in a veneer of legitimacy.

While school segregation wasn’t mandatory, northern primary schools did sometimes exclude Black children. Even in integrated schools, northern racism often meant Black students still received subpar education. Such realities motivated some Black communities to build schools for their children. Boston’s leading Black figure, Prince Hall, once petitioned the legislature to create a public school for Black children. Using language similar to revolutionary-era calls for no “taxation without representation,” Hall and others argued it was unjust for the state to tax Black people while spending no money on their behalf. The state’s legislature denied his request. Hall and other Black Northerners, however, understood the importance of education for their children.9

The Bray Schools

The Williamsburg Bray School.

The Bray Schools were a notable exception to educational barriers. The schools were named after Thomas Bray, a clergyman in the Church of England and founder of missionary organizations. Before dying in 1730, Bray created a charity organization, the Associates of Dr. Bray, to spread Christianity among America’s Black population.10

The Associates’ plan to use education to spread Christianity among the colonies’ Black population was crafted at the same time the very conceptions of childhood and education were changing, due in large part to John Locke’s influential 1690 tract, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, Locke put forth the, at the time, radical idea that childhood should be considered a distinct period in a person’s life, and that children should be treated fundamentally different than adults. In part, this was because the human mind was a blank slate in childhood. By using age-appropriate education and treating children in ways that befitted their age, among other things, Locke believed children could be taught important values and grow up to be civically minded members of society.11

The Bray Schools illustrate how at least some white Anglo-Americans hoped to apply some of the emerging Lockean principles of childhood and education to Black children, thereby accepting that children of the two races held similar capacities to learn. Both had the potential to learn with age-appropriate education. However, instead of creating a society of civic-minded Black adults, the Bray Schools hoped to fill the blank slates of free and enslaved children through a Christian education that taught subordination. Far from being wholly benevolent, the education was very much meant to reproduce and continue systems of oppression by teaching Black children to accept a debased place within society.12

Making Their Own Childhood

From plantations to burgeoning towns, small dwellings to schools, Black children found ways to experience life and grow up that subverted slavery and racial expectations. At least one Bray School scholar in Williamsburg, Isaac Bee, may have used his education as a child to help him self-emancipate. At 18 or 19 years old, Bee escaped from slavery, and his own enslaver was worried that his ability to read, and possibly write, could assist him in dodging authorities.13 While Bee was meant to learn the subservience that supposedly came with his status and race, his childhood instead likely served as a time of development and propelled him towards freedom.

Black children, whether free or enslaved, faced numerous challenges. From being denied opportunities to being denied a proper childhood, these children nonetheless made the best of what was provided to them. From spending time with families, creating toys for play, receiving an education, and escaping slavery, Black children made a life for themselves and those around them.

They surprised those around them with their abilities. All too often made something of nothing. They found ways to play with each other. They discovered how to use their education for their own purposes. They found ways to create communities alongside adults. Their histories show us why histories of children and childhood matter. Instead of simply being a transitional period, childhood was a period when enslaved and free Black children learned some ways to subvert slavery, carve out a place in the world for themselves, and help others.

Sources

- Vincent Carretta, Phillis Wheatley: Biography of a Genius in Bondage (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011), 1, 5-6.

- Michael L. Nicholls, “Aspects of African American Experience in Eighteenth-Century Williamsburg and Norfolk,” Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report, Series 330 (Williamsburg, Virginia: 1991), 14.

- Jennifer L. Morgan, Reckoning with Slavery: Gender, Kinship, and Capitalism in the Early Black Atlantic (Durham: Duke University Press, 2021), 149-150.

- Joseph E. Illick, “Childhood in Three Cultures in Early America,” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies, Vol. 64 (Summer 1997): 316.

- Katherine Wakely-Mulroney, “Isaac Watts and the Dimensions of Child Interiority,” Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies 39, No. 1 (March 2016): 104; Heather Klemann, “The Matter of Moral Education: Locke, Newbery, and the Didactic Book-Toy Hybrid,” Eighteenth-Century Studies 44, No. 2 (Winter 2011): 223.

- Colleen Betti, “‘They Gave The Children China Dolls’: Toys and Enslaved Childhoods on American Plantations,” Master’s Thesis (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2017), 64-73.

- Margaret A. Nash, Women’s Education in the United States, 1780-1840 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2005), 37; E. Jennifer Monaghan, “Literacy Instruction and Gender in Colonial New England,” American Quarterly 40, No. 1 (March 1988), 23.

- Robert Carter Nicholas to Rev. John Waring, December 1, 1772, found in Grant Stanton and John C. Van Horne, “The Philadelphia Bray Schools: A Story of Black Education in Early America, 1758-1845,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 147, No. 3 (October 2023): 82.

- ShaVonte’ Mills, “An African School for African Americans: Black Demands for Education in Antebellum Boston,” History of Education Quarterly 61, No. 4 (November 2021): 478-479.

- Wolfe, Brendan. Associates of Dr. Bray and the Bray Schools. (2020, December 07). In Encyclopedia Virginia. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/associates-of-dr-bray.

- Holly Brewer, By Birth or Consent: Children, Law, and the Anglo-American Revolution in Authority (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for The Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, 2007), 1-5.

- Terry L. Meyers, “Benjamin Franklin, the College of William and Mary, and the Williamsburg Bray School,” Anglican and Episcopal History 79, No. 4 (December 2010): 368-393; Antonio T. Bly, “In Pursuit of Letters: A History of the Bray Schools for Enslaved Children in Colonial Virginia,” History of Education Quarterly 51, No. 4 (November 2011): 429-459; Antonio T. Bly, “‘Reed through the Bybell’: Slave Education in Early Virginia,” Book History 16 (2013): 1-33.

- Bly, “In Pursuit of Letters,” 447; Virginia Gazette (Purdie & Dixon), September 8, 1774 https://research.colonialwilliamsburg.org/DigitalLibrary/va-gazettes/VGSinglePage.cfm?issueIDNo=74.PD.45&page=3&res=LO