Nanyehi (Nancy Ward): A Beloved Woman of Chota

“You know that women are always looked upon as nothing,” the Cherokee woman Nanyehi, or Nancy Ward, told American diplomats in 1781.1

This was a curious sentiment for Nanyehi to express. She was, after all, a respected leader among the Cherokee. Her own life was proof that, instead of being “looked upon as nothing,” women were at the center of eighteenth-century Cherokee society. As the nation’s Beloved Woman, Nanyehi exercised both sacred and political authority. She sat on the nation’s Council and at the head of the Women’s Council.2 When she spoke, people listened.

Yet Nanyehi knew her audience. She knew that the Americans believed statecraft was a man’s job.3 In her 1781 speech, addressed to a triumphant group of Virginia militiamen who had just attacked and destroyed several Cherokee towns during the Revolutionary War, she explained, “we are your mothers[,] you are our sons.” She cleverly called upon ideas of gender that the colonizers, coming from a patriarchal society, would find familiar.4 Moreover, like many white women in revolutionary America, she used motherhood as a source of moral authority and as a unifying force.5 This was also a traditional Cherokee view. “Our cry is all for peace,” she said, “let it continue. This peace must last forever. Let your women’s sons be ours; our sons be yours. Let your women hear our words.”6

A Virginia militia leader responded to Nanyehi: “Such words and thoughts show the world that human nature is the same everywhere . . . We will not quarrel with you, because you are our mothers.” The treaty negotiation ended without the Cherokees losing any land, despite a military loss.7 It was one of many cases when Nanyehi helped the colonists and the Cherokee explain themselves to one another. A skilled speaker, diplomat, and leader, she helped guide the Cherokee people through the tumult of a revolutionary age.

Rise to Prominence

Nanyehi was born around 1738 in Chota, the most important of the Overhill Cherokee towns in what is now eastern Tennessee. She was a member of the Wolf clan (one of seven kinship groups central to Cherokee society) and the daughter of a well-known family.8 Her mother Tame Doe was the sister of Attakullakulla (or Little Carpenter) and a relative of Old Hop, who were two of the most influential Cherokee leaders.9 Cherokee society was matrilineal, meaning that ancestry was determined by the mother’s family. While offices and titles were not hereditary among Cherokee people, Nanyehi’s position in this prominent family would have exposed her to political and diplomatic conversations from a young age.

Attakullakulla in detail of an etching by Isaac Basire (1730).

Nanyehi married a member of the Deer clan named Kingfisher in the 1750s. She accompanied him to the 1755 Battle of Taliwa against the Creeks, who were longstanding enemies of the Cherokee. According to Cherokee tradition, Nanyehi was sitting behind a log, “chewing the bullets” that Kingfisher shot, “so that they would lacerate the more.” When Kingfisher was killed, Nanyehi took his rifle and joined the battle.10 Her brave actions placed her in a long tradition of Cherokee war women, who participated in military actions.11

Beloved Woman

After this display of bravery at Taliwa, Nanyehi was chosen as a Beloved Woman of the Cherokees. In this role, she participated in important rituals. She joined council meetings and advised chiefs. She also had the ultimate authority to decide the fate of captives taken in war: whether they be killed, granted mercy, or adopted into the tribe.12 While Cherokees had no kings or queens, the power and independence of Cherokee women seems to have struck European observers as being similar to royalty. One white observer, for example, remarked on Nanyehi’s “queenly and majestic appearance.”13 She was one of many to earn the designation of Beloved Woman, and the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians continues the tradition today.

In the late 1750s, Nanyehi married an Irish trader named Bryant Ward and was afterward known to colonists as Nancy Ward. Like many traders, Bryant Ward found it useful to marry a Cherokee woman to find his way into their society.14 The marriage also likely helped Nanyehi better understand British colonial society. Two of Nanyehi’s daughters also married traders.15 But like all Cherokee women, Nanyehi was free to marry and divorce at her pleasure. Her marriage to Ward ended quickly. By 1760, he had returned to his white family in South Carolina, though Nanyehi occasionally visited them.16

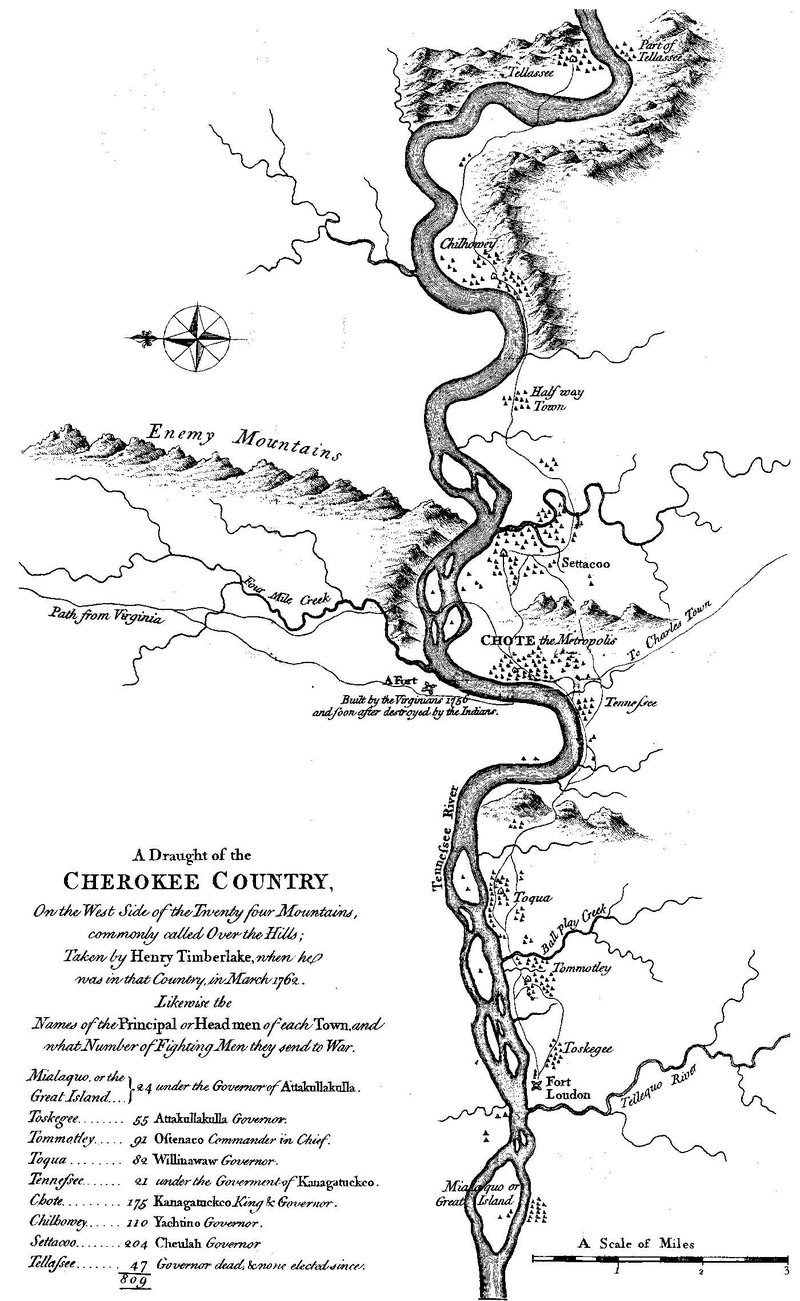

This 1765 map depicts the Cherokee Overhill towns. Henry Timberlake, The Memoirs of Lieutenant Henry Timberlake (1765).

Revolution

During the American Revolutionary War, Nanyehi joined other Cherokee leaders, including her uncle Attakullakulla and Oconostota, to work for peace. Her cousin Dragging Canoe, however, fought a war to protect western Cherokee lands. As war broke out, Nanyehi repeatedly went out of her way to protect American colonists from the warriors who supported Dragging Canoe. After Cherokee warriors captured white settlers living illegally on their lands in 1776, Nanyehi reprieved a settler named Lydia Bean who was about to be burned at the stake. More than once, she warned nearby settler communities of imminent attacks by Dragging Canoe and his warriors, allowing them to flee or prepare.17

When the Virginia militia attacked the Overhill Cherokee settlements in October 1776, they captured but did not burn Nanyehi’s town of Chota. Some believed that the Americans spared the town out of respect for the Beloved Woman.18 When another body of Virginia militia took Chota in 1781, they encountered Nanyehi. The militia officer leading this body reported to Virginia Governor Thomas Jefferson that “the famous Indian woman Nancy Ward came to Camp,” provided “various intelligence,” and “made an overture in behalf of some of the Cheifs for Peace.” Recognizing Nanyehi’s importance, Jefferson responded by asking that “her inclination ought to be followed as to what is done with her.” Her reputation for mercy had earned her the respect of Virginia leaders like Jefferson.

Legacy

Women’s role in Cherokee society changed over the course of Nanyehi’s long life. Reforms in the early nineteenth century empowered all-male institutions and made it more difficult for women to participate in political decision-making. As the Cherokee government came to resemble their American neighbors, women like Nanyehi lost some of their power.19

In 1817, in her late seventies, Nanyehi made her last recorded public act. She joined twelve other women in sending a message to the Cherokee Council, which was considering selling land to the United States. They wrote, “Your mother and sisters ask and beg of you not to part with any more of our lands.”20 This plea did not have the desired effect, as the Americans continued to acquire Cherokee land. After Chota was sold to Americans in 1819, Nanyehi moved to the Ocoee River valley and operated a roadside inn. She died in 1822, just five years before a new Cherokee constitution formally excluded women from political participation.21

After her death, some white settlers developed a romanticized memory of Nanyehi, referring to her as the “Pocahontas of Tennessee.”22 Today, she is a controversial figure among Cherokee people for supporting Americans against Dragging Canoe’s warriors. While interpretations vary, the evidence clearly shows that she was an important historical figure—a warrior, a mother, an orator, and a Beloved Woman.

Indigenous women’s words were rarely recorded during the eighteenth century. Wilma Mankiller, the Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation from 1985 to 1995, once observed that written records generated by men largely ignored the history of Cherokee women: “The voices of our grandmothers are silenced by most of the written history of our people. How I long to hear their voices!”23 Nanyehi is an exception. Because of her prominence in Cherokee diplomacy and politics, her words were occasionally written down. They don’t tell us her whole story (not least because these words were often transcribed by a colonist). But even in their limited form, they offer a portrait of a powerful woman—among many others unnamed—who was committed to peace, mercy, and the sovereign strength of the Cherokee Nation.

Sources

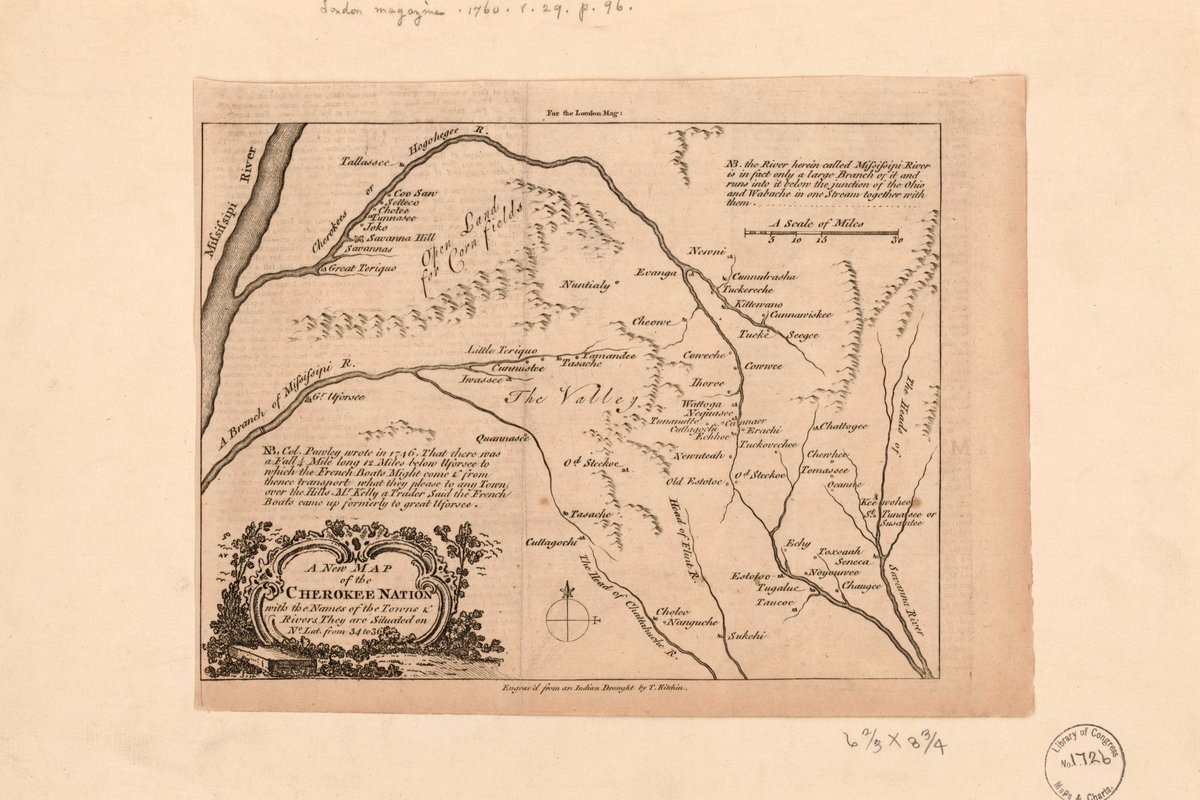

Cover image: Thomas Kitchin, “A New Map of the Cherokee Nation with the Names of the Towns & Rivers They are Situated on,” London Magazine (1760). Courtesy of New York Public Library Digital Collections.

- Quoted in Samuel Cole Williams, Tennessee during the Revolutionary War (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1974), 200. Note that her name is rendered in multiple ways, including Nan-ye-hi and Nanye’hi.

- Paula Gunn Allen, The Sacred Hoop: Recovering the Feminine in American Indian Traditions (Beacon Press, 1986), 32; Ben Harris McClary, “Nancy Ward: The Last Beloved Woman of the Cherokees,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 21 (December 1962): 354.

- Indeed, her uncle Attakullakulla had once asked why Anglo-American delegations excluded women, since “White men as well as red were born of Women.” See M. Thomas Hartley, The Dividing Paths: Cherokees and South Carolinians through the Era of Revolution (Oxford University Press, 1993), 149. Theda Perdue, “Nancy Ward,” in G. J. Barker-Benfield and Catherine Clinton, eds., Portraits of American Women: From Settlement to the Present (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), 85. An American trader once derided the Cherokee for operating under a “petticoat-government,” perhaps a reference to Nanyehi’s power. James Adair, The History of the American Indians (1776; University of Alabama Press, 2005), 182, link.

- M. Amanda Moulder, “‘By Women, You Were Brought Forth into This World’: Cherokee Women’s Oratorical Education in the Late Eighteenth Century,” in Rhetoric, History, and Women's Oratorical Education: American Women Learn to Speak, ed. David Gold and Catherine L. Hobbs (Routledge, 2013), 19–20.

- On the rhetoric of republican motherhood, which Nanyehi’s speech seemed to invoke, see Linda K. Kerber, Women of the Republic: Intellect and Ideology in Revolutionary America (Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1980).

- Williams, Tennessee during the Revolutionary War, 200–201.

- Williams, Tennessee during the Revolutionary War, 201; Perdue, “Nancy Ward,” 94.

- Norma Tucker, “Nancy Ward, Ghighau of the Cherokees,” Georgia Historical Quarterly 53 (June 1969): 192; Perdue, “Nancy Ward,” 87

- McClary, “Nancy Ward,” 353; Tucker, “Nancy Ward,” 193.

- Emmet Starr, History of the Cherokee Indians and Their Legends and Folk Lore (Warden Company, 1921), 468.

- Perdue, “Nancy Ward,” 89–90.

- McClary, “Nancy Ward,” 354; Virginia Moore Carney, Eastern Band Cherokee women: cultural persistence in their letters and speeches (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2005), 24.

- Quoted in E. Sterling King, The Wild Rose of Cherokee, Or, Nancy Ward, "The Pocahontas of the West" (Nashville: University Press, 1895), 119, link.

- Perdue, “Nancy Ward,” 95.

- Clara Sue Kidwell, “Indian Women as Cultural Mediators,” Ethnohistory 39 (Spring 1992): 103.

- McClary, “Nancy Ward,” 355.

- McClary, “Nancy Ward,” 356–57; Perdue, “Nancy Ward,” 90–93.

- McClary, “Nancy Ward,” 358.

- Theda Perdue, Cherokee Women: Gender and Culture Change, 1700–1835 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1998), ch. 6.

- Perdue, “Nancy Ward,” 96–97.

- Carney, Eastern Band Cherokee women, 23; Perdue, “Nancy Ward,” 98.

- Carney, Eastern Band Cherokee women, 21.

- Wilma Mankiller and Michael Wallis, Mankiller: A Chief and Her People (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 1993), 19.