Robert Carter III

The Enigma of Nomony Hall

By the time Robert Carter III was born in February of 1728, the last name Carter was synonymous with many things in Virginia: land, slavery, wealth, and power. His position atop the Virginia elite, as the largest landowner and enslaver, made him one of the richest people in America. Yet by the time of his death, he had spent years in self-imposed exile in Baltimore, most of his family disliked him, and his name drew little more than contempt from his fellow Virginia gentry. As if to emphasize Carter’s fall from the height of Virginia’s aristocracy, upon his death, his family chose to simply bury him in an unmarked grave.

For all he inherited and wielded, Carter is largely forgotten in American history. So, too, is his most consequential action: the execution of the largest individual manumission in United States history before the Civil War. However, Carter’s evolution from a Virginia elite who owned sixteen plantations and enslaved 452 people to an esoteric emancipator is anything but simple.1

Carter embraced revolutionary ideals surrounding slavery and equality, and chose to act on them. But his life was not a linear path towards progress, but a complex story. Nonetheless, more than his fellow Virginians, more than any other elite figure in the revolutionary, Carter took the stated values of the American Revolution to their logical end: if all men were created equal, then no man could enslave another. While certainly not beyond criticism, Carter’s life and actions are a prominent example of how some early Americans not only understood and spoke about how wrong slavery was, but acted on those principles as well.

The Carter Name

The only portrait of Robert Carter III, at about 25 years old. Done by Thomas Hudson in 1753.

Robert Carter III was a fourth-generation Virginian, whose family had been in the New World since the mid-1600s with the immigration of John Carter. Over his life, John bought large swaths of land and grew an unfree labor force consisting of both white indentured servants and African slaves. Robert Carter I built on his father’s success so well that his peers referred to him as “King.” Robert “King” Carter began a personal empire, taking part in many business ventures. He employed a fleet of ships. He built himself and his sons large plantation houses across the Northern Neck region. He left large sums of cash and enslaved people for his daughters and daughters-in-law. When he died in 1732, he left his children more than 300,000 acres of land and about 500 enslaved people to be split among them.2

By the time Robert Carter III was four, both his grandfather and father had died, leaving him to inherit a large portion of the Carter fortune. In 1749, when he turned twenty-one and was old enough to gain his entire inheritance, he became the owner of 65,000 acres of land, more than 100 enslaved people, and his plantation of Nomony Hall. After two rebellious years in London, Carter returned to Virginia, and by 1754 married Frances Tasker, the daughter of a powerful Maryland industrialist. He eventually moved his family to Williamsburg, after being appointed to the governor’s Council in 1758, his first foray into politics after losing two bids for the House of Burgesses years earlier. The Carter family lived in the colonial capital for fourteen years, before the Carters decided to move back to Nomony after losing three children in one year, and becoming increasingly uninterested in Williamsburg life.3

By the time of the American Revolution, Carter was practically a reclusive Virginia aristocrat, having effectively retired from public life. He declined to hold public office and largely kept to his own affairs during the war. One exception was that he provided arms and provisions to patriot forces as the war came closer to home. During this same time, however, he began to undergo a radical change. In 1777, after having his slaves inoculated for smallpox, Carter traveled to Maryland for his own inoculation, only to suffer from a severe fever. Convinced he had died and seen God, Carter experienced a religious reawakening that would have widespread consequences for himself, his family, and the people he enslaved.4

A Changed Man?

Baptism in Schuylkill River. Woodcut from Morgan Edwards – Toward A History of the American Baptists (1770)

The religious experience changed Carter in some important ways. From that point on, he exhibited a voracious appetite for religious writings. He increasingly embraced dissenters, or those Christians who were not part of the Anglican Church. The next year, he would be baptized at a Baptist church he funded on one of his properties. He would travel far and wide just to hear sermons, sometimes riding a horse alone for days just to hear a sermon. He bought volumes upon volumes of various religious texts, going so far as to write to newly widowed women just to inquire if their late husbands had any books he hadn’t yet read and could buy.5

In other ways, however, Carter’s newfound religious fervor hadn’t radically altered his personality. Even before his vision of God, Carter was well known to both white Virginians and local enslaved people as a relatively humane enslaver. He regularly endeavored to keep families together or as close to each other as possible. He provided slightly more food and clothing than most enslavers. And he regularly traded with the people he enslaved, provided them loans, and even paid them using money. Conditions on his plantations, especially Nomony, were healthier and more hospitable. So much so that his enslaved population had a natural growth rate twice that of the average plantation.6

Carter’s treatment of his enslaved people, as well as interest in them, shifted after his religious experience. For example, he joined the Morattico Baptist Church, which began meeting on his Aries plantation, in part because he appreciated the multi-racial, mixed-status, egalitarian nature of the congregation. But his actions going forward didn’t necessarily represent a radical departure. In many ways, Carter was simply uninterested in being an enslaver, displaying the same apathy he had shown towards politics for more than a decade.

By 1780, for example, he began to stop physical punishments for enslaved people, even runaways. However, even though he instructed his overseers and tenants on his plantations to halt such punishments, he made little effort to stop those who disobeyed him in plantations outside of Nomony. Enslaved people would regularly travel to him to seek redress, resulting in him often scolding those who went against his instructions. But he never attempted to stop such disobedience and protect the people he enslaved by firing overseers who skirted his authority.7 Carter’s attitude towards slavery increasingly hovered somewhere between dislike and apathy.

Ending It Slowly

Portrait of Emanuel Swedenborg by Carl Frederik von Breda (1817)

By the end of the 1780s, Carter openly expressed his anti-slavery sentiments to those around him. He sought to distance his children from slavery. He sent his youngest sons, J. T. and George, to a Baptist school in Providence, Rhode Island, that Carter had helped finance. Three of his unmarried daughters were sent to live with a Baptist family in Baltimore, who were given strict orders not to allow the girls to be attended to by enslaved people. And when the fourth daughter announced her engagement, Carter flatly refused to include land or enslaved people in her dowry. He even refused to allow J. T. and George to return home after their mother’s death in October 1787, citing the negative effects of being back in a slave society.8

Around the same time, Carter became increasingly dissatisfied with Morattico Church. Seeking to court wealthier, traditionally Anglican, white southerners, Baptists increasingly accepted slavery and instituted segregation in their churches. Morattico followed suit, which led Carter to help start the Yeocomico Church. He wrote its charter and signed it, along with several enslaved people. At the same time, however, Carter once again began looking elsewhere and became enamored with a fringe Swedish theology originally founded by Emanuel Swedenborg, an aristocrat, philosopher, and scientist. Swedenborg’s ideals advocated for a radically egalitarian vision of Christianity, which was appealing to Carter.9

Carter’s religious and philosophical beliefs had transformed over a decade. This culminated in one of the most radical actions of anyone in the founding generation and after. Dissatisfied with the institution of slavery and his role in it, Carter laid out a plan for the manumission of the many people he enslaved. His 1791 Deed of Gift was meticulously planned. Dry, lengthy, and technically detailed, Carter wasted little time with flowery language inspired by the revolution. His first paragraph simply stated his view that “Slavery [was] contrary to the true principles of Religion & justice.” From there, Carter simply laid out the process through which his enslaved people would gain their freedom.10

Emancipation

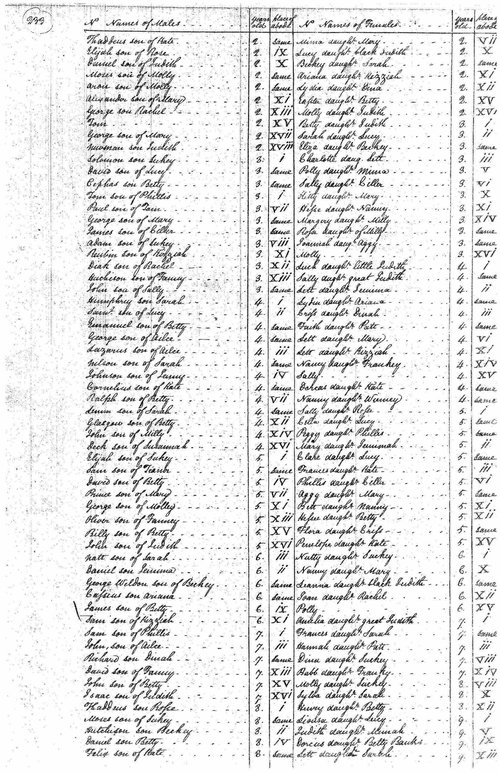

Page from Carter’s Deed of Gift, detailing the name, age, and location of enslaved people.

Carter’s attention to detail in the Deed of Gift was matched only by his focus on making the document legally airtight. Carter knew his actions would be widely unpopular and potentially face legal challenges, not least from his own family. By September of 1791, Carter apparently felt the Deed of Gift was solid enough, and filed it at the country courthouse. Five months later, on February 28, 1792, Carter began taking groups of enslaved people to the courthouse, and manumitting them.11

This process would continue for years. By 1793, Carter was ahead of his own meticulous schedule. He began leasing land to the people he had freed, even turning away potential white renters in favor of his former slaves. By 1797, some of his plantations were completely occupied by formerly enslaved people. His decisions proved just as unpopular among white Virginians as Carter likely imagined. Some of his own family members attempted to refuse his order to send enslaved people to Nomony for freedom.12

One anonymous letter, claiming to speak for the “vast majority of the community,” compared his actions to a man setting his own residence on fire without regard for whether the fire would spread to his neighbors’ homes. It further informed Carter that local enslaved people were attempting to pass as free by claiming to have been Carter’s slaves. The letter also encouraged Carter to relocate his freed slaves in Pennsylvania, where people “seem anxious to have them.” This was a not-so-subtle quip at the state’s active abolitionist societies.13

Leaving Slavery Behind

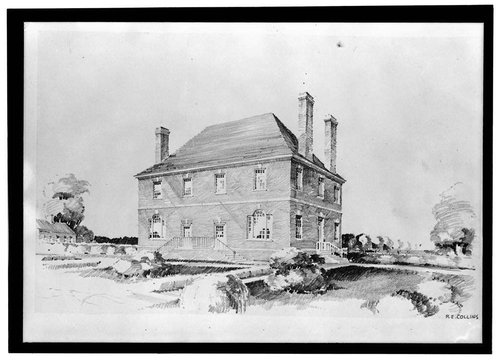

Drawing of Nomony Hall

Carter’s plan had never been, and never would be, done by an enslaver of his status and wealth. But it was also slow and precise. While Carter quickly decided to go ahead of schedule, the full emancipation of his slaves would still take decades, as planned. For his part, Carter’s larger disinterest in being a planter and enslaver meant he didn’t have decades to wait for his plan to finish. He wished to separate himself from Virginia, slavery, and the responsibilities of his status as soon as possible. On May 8, 1793, Carter left Nomony and would never return to Virginia. He bought a modest home in Baltimore. He hosted gatherings of various religious groups, read, and generally lived an uneventful, quiet life.14

In his stead, Carter left the execution of the Deed of Gift to Benjamin Dawson, a rather indifferent, down on his luck, Baptist preacher who had been one of his collection agents since 1789. Dawson was a lazy and corrupt agent, but he also vehemently disliked slavery, apparently the only quality Carter cared about at the time. The preacher carried out manumissions faithfully. By 1796, a combination of Carter’s indifference, his sons’ harassment, and the preacher’s zeal led Carter to split his properties as evenly as possible, randomly giving them out to his sons on the condition they pay him an annual rent an honor existing leases with freed Black people. Finally, Carter sold all of his remaining slaves to Dawson for a single dollar, so that a “full and complete Emancipation” could be realized.15

Dawson continued to faithfully execute the Deed of Gift until his death, despite legal challenges from Carter’s sons. Eventually, Carter grew tired of the preacher’s blatant corruption. While he considered wrestling control of the Deed of Gift from Dawson, his final years were fairly secluded. He died on March 10, 1804.16

A Legacy Forgotten

Robert Carter III occupied a social position equal to, if not above, other Virginians like George Washington and Thomas Jefferson. But today, we rarely speak Carter’s name in the same breath as theirs. Carter was buried at Nomony, in an unmarked grave, and largely forgotten by history. Nomony would eventually become abandoned and overgrown, and never became a major heritage site for the nation’s revolutionary history, in stark contrast to the neatly preserved homes of other Virginia elites.

But why? Why has Robert Carter III, a powerful figure in Virginia’s history and the country’s largest individual manumitter, been forgotten? Only scant references to him and his act dot the multitude of histories on Virginia, the American Revolution, and American slavery. Carter’s only contemporary biographer, Andrew Levy, argues he has been relegated to the far margins of history because Carter’s story runs counter to how many people wish to view the Revolutionary era. Even as people increasingly acknowledge the role of race and slavery in the nation’s history, the American Revolution has stood out as a moment of paradox: freedom and slavery being fought for simultaneously. Levy tells us that version of history, even as it can focus on race and slavery, leaves no room for people like Carter, whose actions don’t fit neatly within that narrative.17

Carter may have done what no other enslaver with anti-slavery views did, but his life shows us one of the main motivating factors was his own desire to live a quiet life, unfettered by the demands a Virginia planter of his status and wealth faced. His life cannot, nor should not, be thought of as a linear path toward enlightened emancipation and equality. Instead, Carter arrived at one of the most radical moments in American slavery through a messy, often contradictory, path, defined by moments of genuine care and detachment. In many ways, his life and actions mirror the story of American history itself, with all its aspirations and contradictions.

The Enslaved People of the Carter Household

Robert Carter III, an unlikely emancipator, brought his young family and enslaved “domesticks” to his Palace Green home in 1761. Carter was a member of the Governor’s Council and the grandson of Virginia landholder, slaveholder, and slave trader Robert “King” Carter.

Sources

- Carter III, Robert. Robert Carter III’s Deed of Gift (August 1, 1791). (2020, December 07). In Encyclopedia Virginia.https://encyclopediavirginia.org/primary-documents/robert-carter-iiis-deed-of-gift-august-1-1791.

- Andrew Levy, The First Emancipator: The Forgotten Story of Robert Carter, the Founding Father Who Freed His Slaves (Random House, 2005), 7-9; Holly Brewer, “Entailing Aristocracy in Colonial Virginia: ‘Ancient Feudal Restraints’ and Revolutionary Reform,” The William and Mary Quarterly 54, No. 2 (April 1997), 322.

- Levy, The First Emancipator, 15-22, 38.

- Levy, The First Emancipator, 76, 78-81.

- Levy, The First Emancipator, 67, 82-84.

- Levy, The First Emancipator, 61-63.

- Levy, The First Emancipator, 107-116, 119-120.

- Levy, The First Emancipator, 126-128.

- Levy, The First Emancipator, 128-144; Shomer S. Zwelling, “Robert Carter’s Journey: From Colonial Patriarch to New Nation Mystic,” American Quarterly 38, No. 4 (Autumn 1986): 629-632.

- Levy, The First Emancipator, 144–45; Robert Carter III, Deed of Gift, August 1, 1791, in Encyclopedia Virginia, 232.

- Levy, The First Emancipator, 144–47.

- Levy, The First Emancipator, 147–51.d

- Levy, The First Emancipator, 155; Transcript of letter found in Meghan E. Banton, “Form and Function of the Colonial Plantation: Recreating the Cultural Landscape of Nomini Hall,” (Longwood University, 2011), 50-51.

- Levy, The First Emancipator, 153–56.

- Levy, The First Emancipator, 157-160.

- Levy, The First Emancipator, 162-163.

- Andrew Levy, “The Anti-Jefferson: Why Robert Carter III Freed His Slaves (And Why We Couldn’t Care Less),” The American Scholar 70, No. 2 (Spring 2001): 15-35; An older Carter biography was written, but spends little time mentioning his actions in manumitting his slaves, Louis Morton, Robert Carter of Nomini Hall: A Virginia Tobacco Planter of the Eighteenth Century (Colonial Williamsburg, 1941).