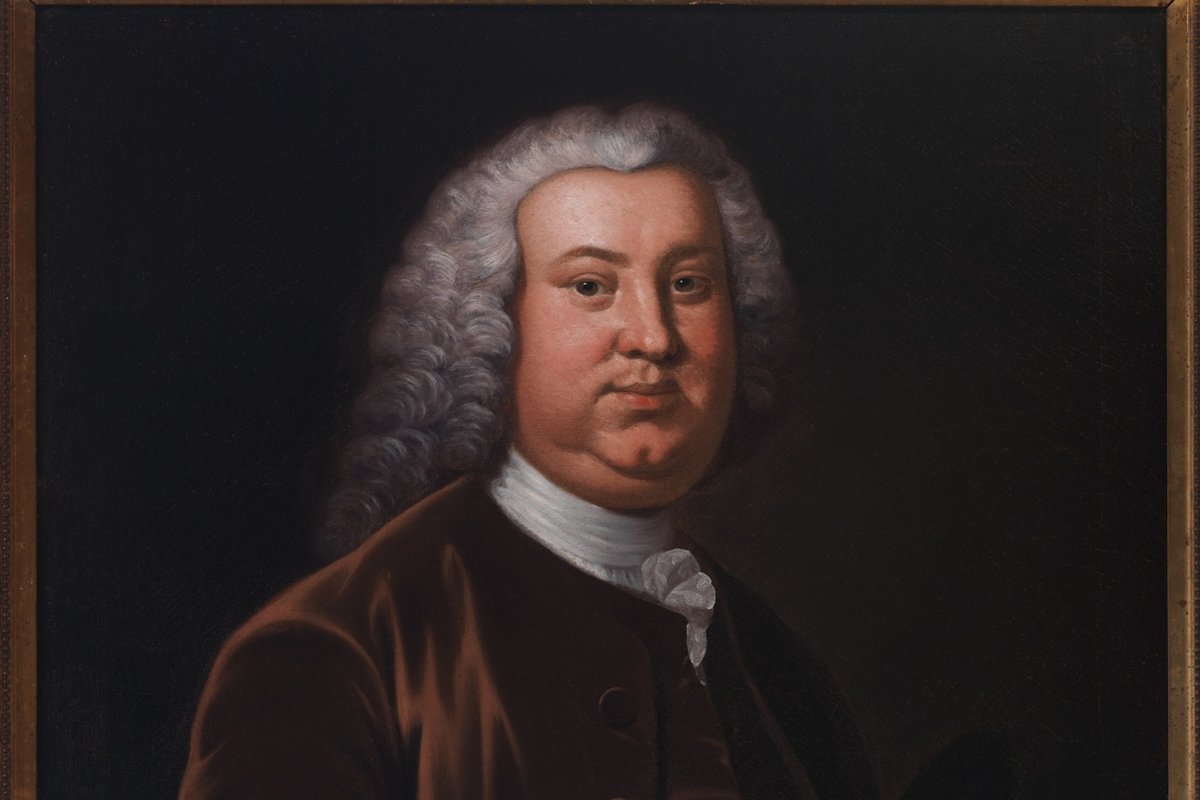

Peyton Randolph of Williamsburg

Virginia’s Moderate Revolutionary

Next In Line

Portrait of Peyton Randolph by John Wollaston (ca. 1755-1758)

Born on September 10, 1721, Peyton Randolph was a third-generation son of a colonial dynasty. The child of Sir John Randolph and Susanna Beverley Randolph, he became a pivotal figure in Virginia politics in the decades leading up to the American Revolution. His grandfather, William Randolph, had migrated to Virginia in the last century, and quickly amassed land, slaves, and wealth. By the time of his death in 1775, Randolph was a powerful landowner, with numerous properties throughout Virginia, where over a hundred enslaved people lived. A little more than two dozen of these enslaved people lived alongside his family at their home in Williamsburg.1

In eighteenth-century Virginia, the eldest son inherited most of his father’s estate. Peyton Randolph was the second son in his family. Despite likely inheriting little, his father’s will singled him out to continue his education. When he died in 1737, his father left him both property and enslaved people, though they went to his mother first. Immediately, however, Peyton was given his father’s entire collection of books, “hoping he [would] betake himself to the study of the law.”2 Two years later, Peyton began studying law in London, which was a relatively rare opportunity for colonists. Randolph would return to Virginia with a far more comprehensive knowledge of the law than many of his fellow Virginians. Upon being admitted to the bar in 1743, Randolph returned to Williamsburg. By the end of the decade he married Elizabeth Harrison, a descendent of the powerful Carter family, had established himself as a representative in the House of Burgesses, and began entrenching himself into Virginia politics and society.3

Political Rise

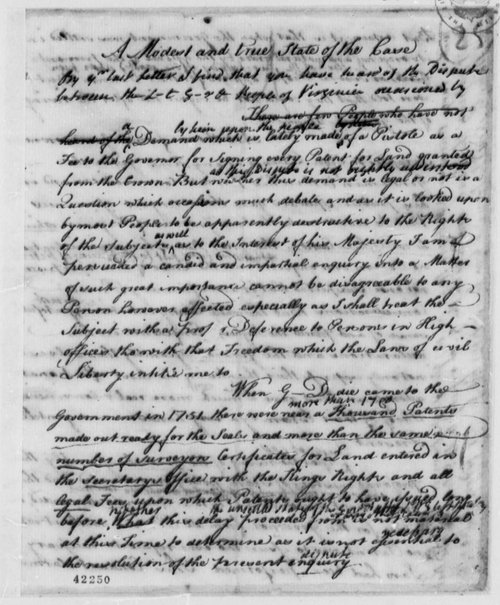

Richard Bland, Draft Statement on Pistole Fee and Land Patents (1753)

Randolph quickly rose to power in Virginia politics. Along with becoming a Burgess, he was also named attorney general for the colony. Despite being a junior member of the House, Randolph was selected to serve and chair important committees usually reserved for senior Burgesses. Yet his political position was not without its challenges. In the early 1750s, he was forced to balance the interests of his fellow colonists against those of the royal government when Lieutenant Governor Robert Dinwiddie enacted a new tax, seizing a power traditionally left to the legislature.4

The so-called Pistole Fee Dispute arose when Dinwiddie required the payment of one pistole, about eighteen shillings, for affixing the colony’s seal to land patents. Virginians fiercely opposed the tax, viewing it as a power grab by the governor. Randolph was selected by the House to personally plead their case to the Crown in England. As attorney general, it would have fallen to Randolph to defend Dinwiddie’s actions, and so before sailing for London, he temporarily resigned his position. While Crown officials delivered a compromise decision in the end, limiting the tax’s application while affirming the right of the governor to lay it, Virginia colonists nevertheless counted it as a win. The Board of Trade ordered Dinwiddie to immediately reappoint Randolph as attorney general, and upon return to Williamsburg he was promptly reelected to the House of Burgesses, where his colleagues were impressed by his handling of the case.5

A Revolution Begins

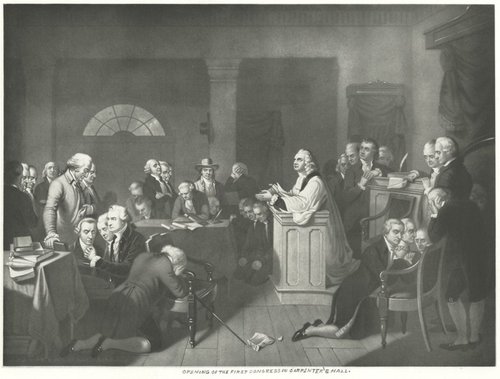

Patrick Henry Before the Virginia House of Burgesses by Alfred Jones (engraver) and Peter Frederick Rothermel (artist) (1852)

Randolph was not without his challengers. When the passage of the Stamp Act sparked a colonial crisis in 1765, Randolph dissented. But he did so in a restrained, even conservative, manner. He was selected to help draft a resolution against the Stamp Act. The result was a document that couched the colony’s right to tax itself within deferential language. While Randolph accepted this tone, other members rallied behind a bolder approach championed by a firebrand new member of house, Patrick Henry.6

Henry, who had already made a name for himself previously, introduced five resolutions he hoped would be adopted by the legislature. While largely restating accepted principles, the resolutions dropped the ceremonial language of deference, and along with Henry’s speech, appeared extreme and possibly treasonous to moderates like Randolph. They narrowly passed though, with the fifth and most incendiary one doing so by a single vote.7

Randolph, for his part, was incensed. Thomas Jefferson, who was then a student, observed the debate at the time. He later recounted how the radical fifth resolution had passed by a single vote. Likely storming out of the chambers, Randolph told Jefferson that “By god I would have given 500 guineas for a single vote.” Randolph and other moderates were able to have the resolutions stricken from the record the next day, after many more radical members had left. But the printing of Henry’s resolutions afterwards would have certainly angered Randolph.8

As Randolph stormed out of the legislature’s chambers, he was likely followed by his longtime personal attendant, an enslaved man named John Harris. Just as Randolph was witnessing the growing revolutionary movement, Harris would have too, always being close to his side. What did Harris think of such revolutionary talk? What about the dozens of other enslaved people who attended to the Randolphs in their Williamsburg home? What did they think of the colonists decrying tyranny and political enslavement? While we don’t know exactly what they thought, we can be sure that they had their own opinions on the matters at hand.

A New Speaker

Continental Congress, 1774 by Henry S. Sadd (Engraver) and Thompkins Harrison Matteson (Artist) (ca. 1860). From the New York Public Library

The next year, in 1766, Randolph would join his father and grandfather in holding the position of Speaker of the House of Burgesses. Over the next years, Randolph oversaw not only the regular business of governing the colony, but also helped craft and moderate Virginia’s response to ongoing colonial tensions. During these years of colonial unrest, however, Randolph’s health became increasingly poor and unstable. In 1774, when he was selected as a delegate to the First Continental Congress, the Virginia Convention passed a resolution selecting Robert Carter Nicholas as an alternate in the case Randolph was physically unable to attend.9

Randolph did make it to Philadelphia and represent Virginia. When the Congress met, they unanimously selected Randolph as president, illustrating how much the political elite in other colonies held him in high regard. When Congress attended to its business, Randolph returned to Virginia, where he continued organizing colonial responses, communications, and government.10

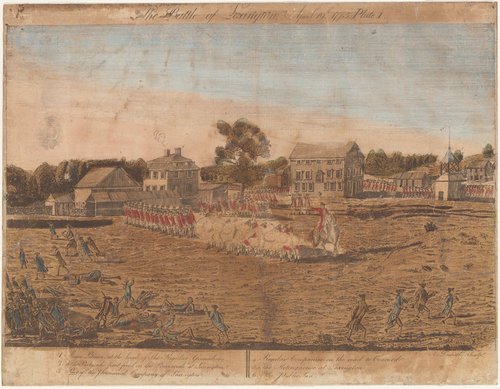

An Explosive Situation

The battle of Lexington, April 19th. 1775. Plate I. From The New York Public Library.

On April 21, 1775, Governor John Murray, the earl of Dunmore, ordered the relocation of the gunpowder from the Williamsburg Magazine. Mob rule nearly ensued. But Randolph and others were able to convince people to take a more civil approach. Randolph personally delivered an address from the people of Williamsburg to the governor. Randolph reported the Governor assured him the gunpowder was only moved out of an abundance of caution due to a rumored slave insurrection in a neighboring county. It could easily and quickly be brought back if needed. The response didn’t inspire confidence. But because they wanted to avoid violence, Randolph and others convinced the townspeople to disperse.11

Over the next week, tensions continued to build. Dunmore requested another meeting with Randolph when news arrived in Williamsburg that nearby militias were organizing to march on the Governor. Randolph convinced the growing multi-county coalition force to disperse, and avoided bloodshed in Virginia. Just days earlier, the first shots of the Revolutionary War had been fired in Lexington and Concord in eerily similar circumstances. That Williamsburg didn’t experience the same situation was due in large part to Randolph’s leadership. Having been selected to attend the Second Continental Congress, Randolph left for Philadelphia at the conclusion of this stressful event.12

The Final Congress

Assembling in May, the Second Continental Congress also selected Randolph as its president. Randolph quickly left, however, when he received word that Dunmore had summoned the Virginia Assembly to meet on June 1. Rumors also swirled around the possibility of emancipation being offered to enslaved people who came to Dunmore’s aid. When Randolph arrived in Williamsburg, he found a town on edge. The townspeople feared for Randolph’s safety and insisted on escorting him to his home. Tensions rose after Dunmore’s opening address to the newly assembled Assembly, in which he attempted to reassert his authority. The whole affair came to a head when Dunmore abandoned Williamsburg out of fear for his safety, essentially leaving the legislature, with Randolph at its head, in charge of the entire colony.13

Randolph called for a convention in Richmond the next month, to better decide on a course of action. Though he tried to preside over it, his health became such an impediment that it slowed proceedings. Other members respectfully and quietly replaced Randolph after a few weeks with Robert Carter Nicholas, and he returned to Williamsburg to recover some strength before setting back out for the Congress.14

By September 13, Randolph was once again present at the Congress. Much to the embarrassment of some members, John Hancock, who had been selected as president in the meantime, refused to give up the position. Given his precarious health, however, it is likely Randolph, and others, were glad he had essentially ceded the responsibilities of a demanding position. While Randolph would participate in some committees, that came to an end on upon his death on October 22, when he suffered a stroke while dining with Elizabeth and Thomas Jefferson at the home of Henry Hill, a local wine merchant.15

Legacy

In his will, Randolph left the vast majority of his property and holdings to Elizabeth. He empowered her to sell what properties and items to cover his debts, as well as any enslaved people. Elizabeth would eventually return to Williamsburg, escorted home by Edmund Randolph, Peyton’s favorite nephew, and John Harris.16 Peyton Randolph’s death meant he would not witness the still revolutionary moments to come. But he nevertheless paved the way for them as a leading figure in Virginia politics during the pivotal decades leading into the American Revolution.

People of Williamsburg

Eighteenth-century Williamsburg was a community on the brink of revolution. Learn the stories of ordinary people during extraordinary times.

Sources

- Peter Inker, “Why We Chose to Center the Lives of the Enslaved in Our Newest Virtual Tour of the Randolph Site,” (Colonial Williamsburg, 2021), https://virtualtours.colonialwilliamsburg.org/randolph/.

- John J. Reardon, Peyton Randolph 1721-1775: One Who Presided (Carolina Academic Press, 1982), 5.

- Reardon, Peyton Randolph, 5.

- Reardon, Peyton Randolph, 9-10.

- Reardon, Peyton Randolph, 14-15.

- Reardon, Peyton Randolph, 20-21; John Pendleton Kennedy, ed., Journals of the House of Burgesses of Virginia, 1761-1765 (Library board, Virginia State Library, 1907), 360-361.

- Harlow Giles Unger, Lion of Liberty: Patrick Henry and the Call to a New Nation (Da Capo Press, 2010), 38; Robert Middlekauff, Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789 (Oxford University Press, 2007), 56; Reardon, Peyton Randolph, 22.

- Middlekauff, Glorious Cause, 56; Reardon, Peyton Randolph, 22-23; “Thomas Jefferson’s Notes on Patrick Henry, [before 12 April 1812],” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-04-02-0496-0003.

- Reardon, Peyton Randolph, 41, 46-48; Robert Scribner, ed., Revolutionary Virginia: The Road to Independence, Vol. 1: Forming Thunderclouds and the First Convention, 1763-1774 (University Press of Virginia, 1977), 234.

- Reardon, Peyton Randolph, 48-50.

- Reardon, Peyton Randolph, 58-59.

- Reardon, Peyton Randolph, 59-60.

- Reardon, Peyton Randolph, 60-62.

- Reardon, Peyton Randolph, 65.

- Reardon, Peyton Randolph, 68; Jon Meacham, Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power (Random House, 2013), 94.

- Reardon, Peyton Randolph, 69, 72; Mary A. Stephenson, “Peyton Randolph House Historical Report, Block 28 Building 6 Lot 207 & 237,” Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series – 1536 (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1967), 153.