Crafting the Perspective of Enslaved Historical Figures

Embodying the persona of enslaved persons has enhanced my artistic development, expanded my mind, and forced me to go places within myself I never would have imagined. ‘Enslaved’ is an out of character term used to provide humanity to the people who were held in bondage. The law was the determining factor that deemed them ‘slaves,’ but that is not who they were. Half of Williamsburg’s population in the 18th century were people of African descent. The majority of this population were enslaved.

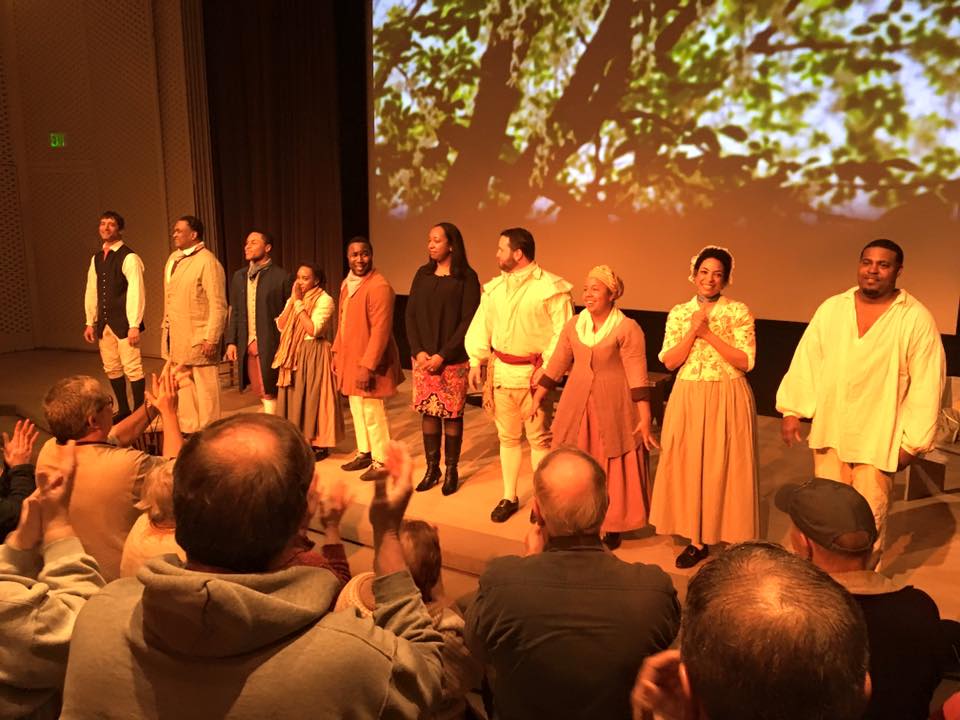

These historical figures are constantly inspiring me through their resilience and resourcefulness, and I am fortunate to be able to relay the impact of their existence to guests from around the country and globe. Here at Colonial Williamsburg there are many interpreters with vast backgrounds and extensive knowledge about enslaved people and the 18th century. Below, I will share questions I have frequently received while in character and my corresponding answers based upon my research in this field and experiences portraying these historical figures.

“WHAT DO YOU DO?”

Jupiter would respond, “It is my duty to attend Mr. Jefferson. I dress him, run errands for him; and wherever he goes I am not too far behind.” As Thomas Jefferson’s enslaved manservant these would have been some daily activities for Jupiter. He and Jefferson were both born in 1743 and grew up together on Shadwell plantation. By 1775, Jupiter’s role as manservant ended and he functioned as the head of the stables at Monticello until his death in 1800. I often think on Jupiter’s life and how intertwined it is with the service he provided to the person who owned him. I wonder what were his thoughts and dreams outside of his duties as personal servant or stable head. "Those Who Labor for My Happiness": Slavery at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello by Lucia Stanton has been one resource I have used to develop Jupiter’s perspective.

Speaking the names of enslaved individuals is particularly vital because sometimes that is all that is available to us. A name and the monetary value assigned to their life. Sometimes we discover their work or duties performed in the household. By speaking their names we attempt to honor the life not the worker. The historical figures I portray were skilled in a variety of arenas. I have portrayed and interpreted a wide range of people, such as Jupiter (manservant), Jemmy (stable hand from the Raleigh Tavern), Roger (a footman), Johnny (a waiting man), James (a gardener from the Palace), and Mingo (a carpenter).

Mingo, enslaved to Benjamin Powell, would grumble, “Today I’ve been hired out to repair a few broken chairs and fix some stuck windows at the Raleigh Tavern. It will be a long day, and it will end with Master Powell receiving money for the work I done.” Benjamin Powell was an undertaker in Williamsburg who acquired several construction contracts including the Public Gaol and the steeple at Bruton Parish Church. Primary sources such as account and record books inform us of the practice of hiring out enslaved people. A slave owner would hire out their enslaved person to complete a task or fulfill a need for another individual and the owner would be monetarily compensated for the work of the enslaved. I interpret that Mingo is a highly skilled carpenter whose spirit has been broken due to a traumatic event. There may not have been the vast terms, diagnosis, or medical practitioners that we have today but I wonder about the mental health of the enslaved, especially someone such as Mingo. In July of 1772, Mingo was accused of stealing a sheep from the Royal Governor of Virginia. He received 25 lashes at the public post and was branded on his left hand with the letter ‘T’ for thief.

“ARE YOU FREE?”

“Yes, I am. My mother is free and that made me the same,” declares John Ashby Jr, the only free black man that I portray in the Historic Area. John is referencing a 1662 law that states “all children borne in this country shalbe held bond or free only according to the condition of the mother.” A free woman’s child would be free and an enslaved woman’s child would be enslaved. I often consult and examine Hening’s Statutes at Large, which intimately detail Virginia law dating to the 1600’s and provides great insight to laws that bound both free and enslaved black people. It is important to note that not all black people in Williamsburg were enslaved during the Revolutionary war period. The majority were, however, there was a very small population of free blacks, most of whom were born with their freedom, residing within and around the area at the time.

Imagine how an enslaved person might feel about freedom if they were within a household of a signer of the Declaration of Independence such as George Wythe. I interpret Abram as a figure to represent Black fatherhood during the institution of slavery. As a father of two young enslaved boys Abram states, “Yes. I am free in the eyes of God, but if you want to know about law…that is something different.” Being in the household of one of the city’s most prominent educators and figures I infer that Abram is very conflicted with the concept of freedom. He is within proximity of proponents of freedom and independence, yet he and his family remained in bondage.

“IS YOUR MASTER GOOD TO YOU?”

My research and character development highlights that there is no singular experience that enslaved people share during this time period, including what could constitute an owner being ‘good’. Their work, circumstances, locations, and enslavers are all different, but the commonality of enslavement is the unifier. Under law, all of these human beings were considered to be property of another human being. The reality of this time is unimaginable for us today, but it was theirs to endure.

I interpret Wentworth to be a waiting man at the Charlton Coffeehouse. He laments, “I haven’t seen my Papa in over a year and I have to ask another man, who purchased me, for permission to see him. Nothing good about that to me.” Wentworth was a real person but he was hired out to Richard Charlton after 1767 when the coffeehouse had become a tavern so his actual experience falls a few years outside the time period I interpret him. As a teaching tool I center his origin story at Shirley plantation (which is in nearby Charles City County, VA) and focus on the longing he has to reunite with his family and loved ones. He has not seen them in quite some time because of the work demands of his new owner. It is no secret about the selling and purchasing of the enslaved. I think heavily about the isolation. How does it feel to be removed from the community that you’ve always known and the person who is now in closest proximity is your ‘new’ owner? How is one supposed to feel?

Roger reflects, “I maintain distance from Mistress as much as possible. She has good days and days that are not so good.” Roger was one of 27 enslaved on the Randolph property, and the Randolphs were one of the wealthiest and influential families in Virginia. He was valued at sixty pounds and sold to David Ross of Petersburg in December of 1779. Roger had been on the Randolph property since he was a child.

“WHY DON’T YOU JUST RUNAWAY?”

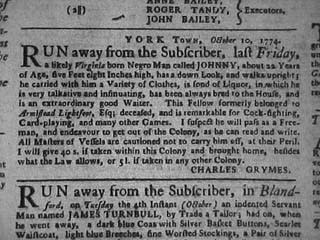

Runaway advertisements are one of the greatest resources that we have to learn about the lives, personalities, and skills of enslaved people. They are documented proof that thousands of people ran away daily in an attempt to obtain their freedom. Running away was dangerous due to the threat of being captured and punished, and not an easy decision if it meant leaving family and friends behind. An individual could run away but the act might have communal ramifications for those left behind.

Before he was sold Roger would say, “I have contemplated it many times, but I cannot leave my sister and her children. I must be here for them. What would happen if I just left them behind?” The Philipsburg Proclamation was issued on June 30, 1779 by the British and it offered protection and freedom from masters if the enslaved made it to British lines. Roger may not have taken the opportunity to run before he was sold, but in total eight people of the Randolph house ran away and are believed to have crossed to British lines.

Johnny, an enslaved waiter to Charles Grymes, was determined to live life as a free man. “I’m going to be free.” Johnny ran away in October of 177

“HOW ARE YOU ABLE TO DO THIS?”

I join all the historical figures I represent in saying, “I need to tell my story.” People often inquire what it is like to portray enslaved persons every day and how I can continue the work. The truth is every day is unpredictable. As I watch the current news or social media feeds, I sometimes question whether I still have the capacity to put these clothes on and tell this story. I have been doing this work for over six years, yet this year is the heaviest the work has ever felt. There is heaviness in our country, but there is also change in the air. I have never experienced such palpable demand and desire for fundamental change in our nation and that encourages me deeply. We are living and witnessing monumental moments in our history. That inspires me to continue telling these stories and representing these people. Their lives and experiences are a part of the moment that we are witnessing now. Their existence mattered. I’m grateful when someone can walk away from a performance or interpretation knowing the life of a particular enslaved individual. They were all throughout the historic city of Williamsburg. It is not always easy reading and digesting the painful truth of slavery, but it happened and it is a part of our collective history. I am able to continue this work because it is an honor to represent these incredible people and they should never be forgotten.

Jamar Jones, a member of the Actor Interpreter department, has been acting and crafting historically based theatrical experiences for guests for six years. Jones views his work as “a beautiful challenge.” He reflects, “It is sometimes difficult researching and unearthing the stories of enslaved people because there is pain and hurt; but there is also beauty. The people, their lives, and their sacrifice…I consider it a privilege and an honor to represent them every day. I want them to be proud.”

Resources

William Waller Hening, ed., The Statutes at Large; Being a Collection of All the Laws of Virginia from the First Session of the Legislature, in the Year 1619 (New York: R. & W. & G. Bartow, 1823), 2:170.