Folk artist Lewis Miller described his sketches as “chronicles.” His art documented everyday life wherever he traveled, and the watercolors in his mid-19th-century “Sketchbook of Landscapes in the State of Virginia” include landscapes, farms, towns and small figures of people and animals.

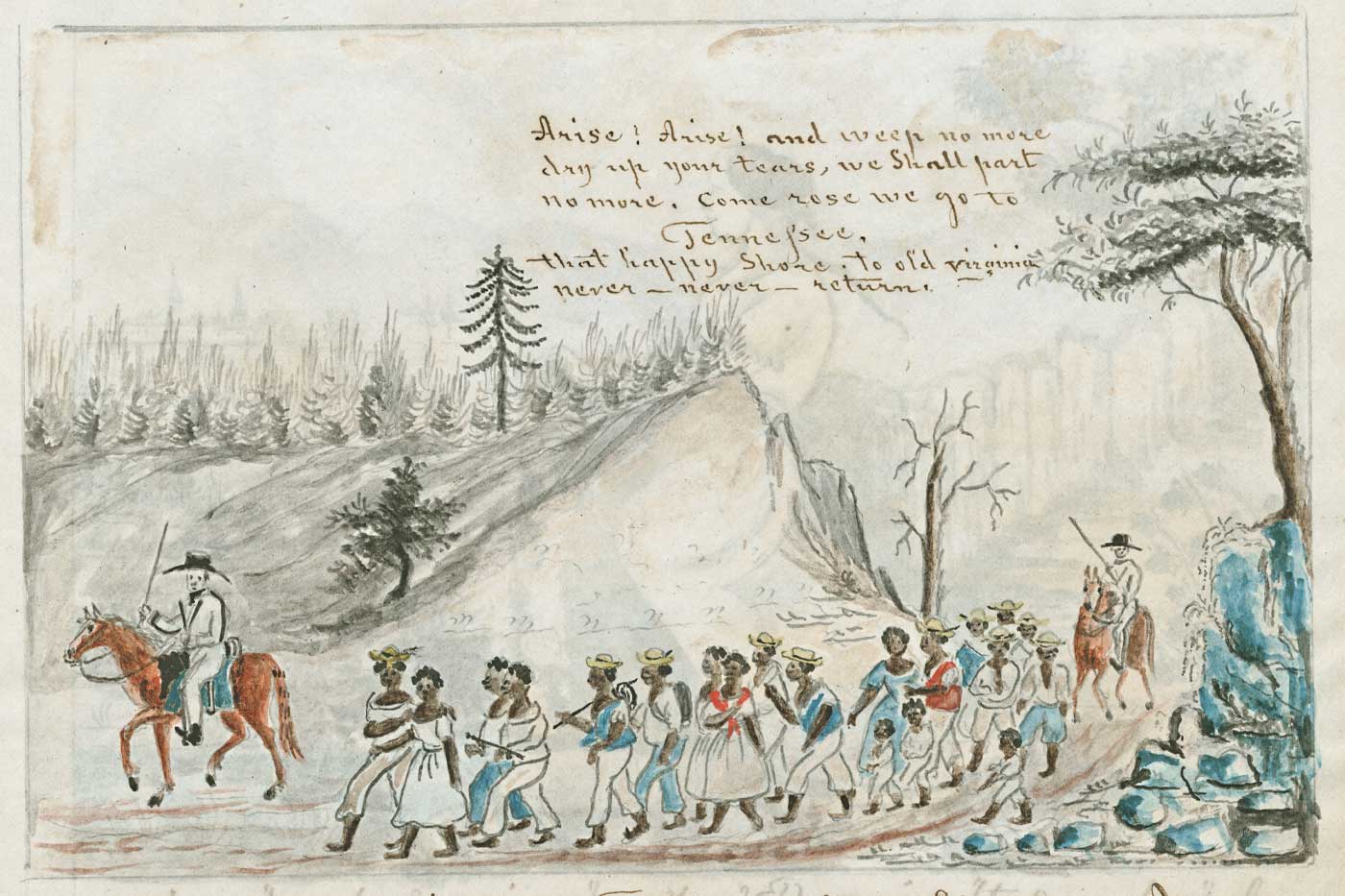

Among the scenes Miller sketched into his notebook is a coffle — a group of enslaved people being transported in chains. The pictured coffle consists of 20 enslaved men, women and children who had been bought in Staunton, Virginia, and were being taken to Tennessee. Under the illustration, Miller wrote that coffles were “commonly in this State, with the negro’s in droves Sold.”

Coffles, according to historian Steven Deyle, “could be found on every southern highway, waterway, and railroad.”

Between the Revolution and the Civil War, more than 1 million enslaved people were sold and transported from the upper South, including Virginia, to states farther south and west. Coffles generally consisted of 30 or 40 enslaved people, with men handcuffed and chained and women and children walking or on a wagon behind the men. They were routinely forced to walk 20 to 25 miles in a day.

Art historian Maurie D. McInnis noted that 19th-century abolitionists saw coffles much as earlier abolitionists saw the Middle Passage, by which Africans were forcibly transported to the New World: Both could “communicate the horrendous conditions of the slave trade.”

Before the Revolution, most enslaved people came to Virginia from Africa or the West Indies. In the 19th century, the slave trade became more of a domestic operation, in part because Virginia’s planters had shifted from growing tobacco to growing grains, which required less labor, and at the same time, the cotton gin led many planters farther south and west to grow cotton, which was very labor intensive.

In addition, by this time, enough children were being born to enslaved people to more than satisfy the needs of Virginia’s planters for labor.

With a surplus of enslaved people in Virginia and a shortage of labor farther south, coffles were, as Miller noted, a common site. They were most common in the fall, allowing the enslaved to arrive in the winter and be available for the early spring planting season of the lower Southern states.

Richmond became the largest slave trading center in the upper South. Auction houses were located in the Shockoe Bottom area of the city, as were jails where enslaved people were held before being auctioned and then again until there were enough sales to form a coffle.

Ironically, the domestic slave trade also grew because of measures that were passed to make Virginia more democratic. When Thomas Jefferson returned from Philadelphia after drafting the Declaration of Independence, he was intent on creating a republic in Virginia that treated citizens more equally. He pushed for getting rid of entail, which barred landowners from selling or dividing inherited property, and primogeniture, which required estates to be passed on to the oldest son. The legislature passed the first measure in 1776 and the second in 1785.

Jefferson later wrote that these legal reforms, the credit for which he shared with George Mason and George Wythe, laid a foundation “for a government truly republican.” He did not consider the effects of these reforms on enslaved people, whom he certainly did not recognize as citizens. But, by breaking up large estates, the new laws split up the communities of enslaved people on those estates. Wrote Deyle: “The dismantling of large estates was seen as a democratic improvement by white Americans, yet it produced drastically different results for American blacks.”

Similarly, the United States’ abolition of the transatlantic slave trade in 1808 was generally trumpeted as a humanitarian triumph. Virginia had banned importing slaves from Africa as early as 1778. But those measures, too, led to the growth of the domestic slave trade. Once it was illegal to import slaves from Africa, planters in the Deep South who wanted more slave labor instead bought from those farther north, including especially Virginia.

George Washington was among those who had more slaves than he needed. He complained in 1799 about having “more working Negros...than can be employed to any advantage in the farming System.” Washington disliked buying and selling slaves: he was, he wrote, “principled against this kind of traffic in the human species.” But it benefited him financially to do so.

Miller’s attitudes toward coffles and slavery are not clear. He saw himself as a chronicler and not an activist. Above his sketch of the coffle, he wrote words the enslaved people may have been singing: “Arise! Arise! and weep no more / dry up your tears, we Shall part / no more. Come rose we go to / Tennessee, / that happy Shore. To old Virginia / never — never — return.”

McInnis noted that these lyrics had a double meaning. They were, McInnis wrote, “calculated by slaves to express the contentment that slave owners wanted to hear, as if the sorrow of leaving their homes and families in Virginia was merely a passing thought to be replaced with visions of Tennessee, ‘that happy shore,’ even as they commiserated with one another over the hard truth and finality of the last line, ‘never — never — return.’”

Miller wrote about the coffle that he was “astonished at this boldness,” but it is not clear that indicated disapproval. In another sketch, which portrays two Blacks caring for a Virginia racehorse, Miller wrote, “They were a contented and a happy race.”

Another watercolor from the sketchbook, Miss Fillis and Child, and Bill, Sold at Publick Sale, not only shows the prices for which the subjects of the sketch were sold — $600 for the woman and child and $800 for the man — but also various bids offered by would-be buyers.

Yet another watercolor from the sketchbook, Represents Our Next Door Neighbor, pictures Black people at work but Miller seems less interested in their enslaved condition than in exemplifying “domestic & native industry,” the motto on the banner held by the man in the middle.

Whatever Miller’s own thoughts, his drawings of enslaved people are a rare and valuable resource for historians. “Miller’s observations,” said Laura Pass Barry, Colonial Williamsburg’s Juli Grainger Curator of Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, “provide a visual perspective that complements contemporary written records.”

Slave Trader, Sold to Tennessee

Artist Lewis Miller

Date circa 1853

Medium Watercolor

Notes Slave Trader, Sold to Tennessee was a page in Miller’s “Sketchbook of Landscapes in the State of Virginia.” Two of Miller’s sketchbooks were donated to Colonial Williamsburg in 1978 in memory of George Hay Kain, one by Dr. and Mrs. Richard M. Kain and one by Mr. and Mrs. William H. Kain.

Getting to Know Lewis Miller

Lewis Miller (1796–1882) was raised in York, Pennsylvania. Known to his friends as “Louie,” he worked as a carpenter, but relatives encouraged him to pursue his artwork. He lived with his parents until their deaths, in 1822 and 1830, after which he traveled a great deal. He frequently visited his brother Joseph Miller, who was a doctor in Christiansburg, Virginia. He continued to visit Virginia after his brother died, often exploring surrounding areas.

“Miller’s sketches are personal reflections of the world around him combining his intellectual curiosity, keen sense of observation and interest in local history,” said Laura Pass Barry, Colonial Williamsburg’s Juli Grainger Curator of Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture. “While his drawings meticulously record daily life, they were never meant for publication, and thus, as part of his private collection of journals and diaries, they offer an honest, direct and intimate reflection of historic and contemporary events.”

Most of his Virginia sketches are in the collections of the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum and the Virginia Museum of History & Culture in Richmond.