In mid-18th-century Virginia, wallpaper with expansive printed patterns was found hanging in the homes of gentry people — people with names like George Wythe and Thomas Everard. And with good reason.

The process for producing these papers was akin to creating works of art.

The earliest evidence of wallpaper in Williamsburg dates to around 1755 — before paper was available in rolls. Instead, sheets of paper made from the pulp of textiles, often linen rags, were glued together in the size needed for the space. A ground color was painted onto the paper, and when a pattern was part of the equation, wood blocks were hand carved, one for each color or variation needed in the design.

Curator Margaret Pritchard discovered all this the hard way.

By the mid-1990s, Pritchard and her colleagues had evidence that there had been wallpaper in the Thomas Everard House, and supected it had been hung in the George Wythe House.

With that was born an interest in learning more about how wallpaper was made in the 18th century, and it became an exercise in learning largely by doing. Pritchard recalls gluing papers together in the attic of her home and then painting the ground color onto the rag paper before shipping it off to a company in England that re-created historic wallpapers. There, a block-printed design reproduced from a sample in the Foundation’s collection would be added.

“We kept researching exactly how they printed these papers in the 18th century, and we started collecting as much 18th-century wallpaper as we could,” said Pritchard, now the deputy chief curator for the Foundation.

Today, the work on historic papers continues, though the methods have evolved. Instead of gluing papers together in the attic, conservators use scientific methods to analyze and date papers in the Foundation’s collection, and a company called Adelphi Paper Hangings produces the papers to the curators’ and conservators’ specifications.

Adelphi, founded in 1999 and based in New York, is the only commercial production facility for block printing historic papers in the United States. Colonial Williamsburg was among its first clients.

“We try to keep the materials and processes as traditional as we can,” said Steve Larson, who owns Adelphi along with Chris Ohrstrom, though some material and methods for producing the paper are modern by necessity.

An Adelphi team draws, by hand, transparencies for each color in the wallpaper pattern. In a nod to technology, the design elements are burned into the wood blocks that are used for printing. The company creates its own paint, guided by the scientific analysis provided by Colonial Williamsburg, and prints on papers primarily made of cotton.

It was an exacting process in the 18th century, as it is now, to place the blocks so that the design renders properly. Larson said it’s not unusual to find mistakes in historical papers, so much so that when his team finds a mistake in an example from the 1700s, they call it “historically accurate.”

The relationship between the Foundation and Adelphi has been mutually beneficial. When European wallpaper companies began shutting down during the 20th century, Adelphi began to accumulate the tools used to create the patterns — especially the wooden blocks— and immersed itself in the 18th-century method of producing wallpaper.

“They’re quite a resource for us too. They started rescuing the blocks to have them in their collection — information that would be lost without them. Wallpaper rarely survives because usually it is removed when tastes change and also because it is fragile,” said Emily Campbell, an associate in the Foundation’s Architectural Preservation and Research Department.

Campbell was part of a team that examined two historic papers that will join nine other designs Adelphi has produced, based on items from Colonial Williamsburg’s museum collection.

Colonial Williamsburg’s product licensing division, Williamsburg brand, recently selected the two designs from the Foundation’s collection. The ornamental papers are from the late-18th century and the 19th century, one from inside a trunk and the other from a cupboard.

The Foundation provides research that dates the papers and the scientific analysis to help Adelphi match the colors of the original as closely as possible.

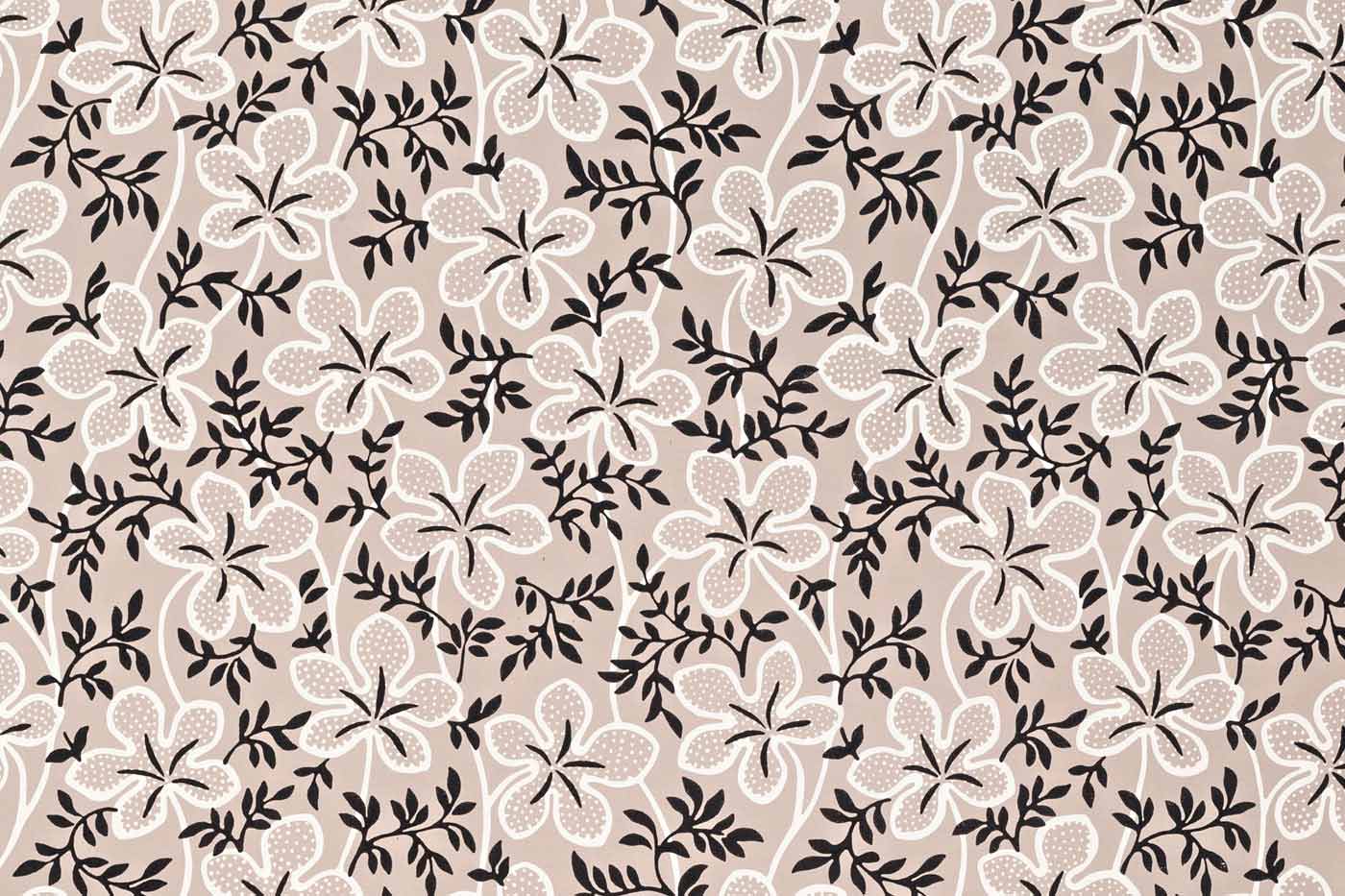

One of the new patterns, a paper found inside a cupboard purchased in Blowing Rock, North Carolina, and its pigmentation included two different types of carbon black particles: one derived from charring plant material, the other made up of the fine particles collected from a sooty flame.

“It probably only needs two, maybe three blocks total,” Campbell said. The typical Adelphi job, Larson said, involves patterns with three or four colors.

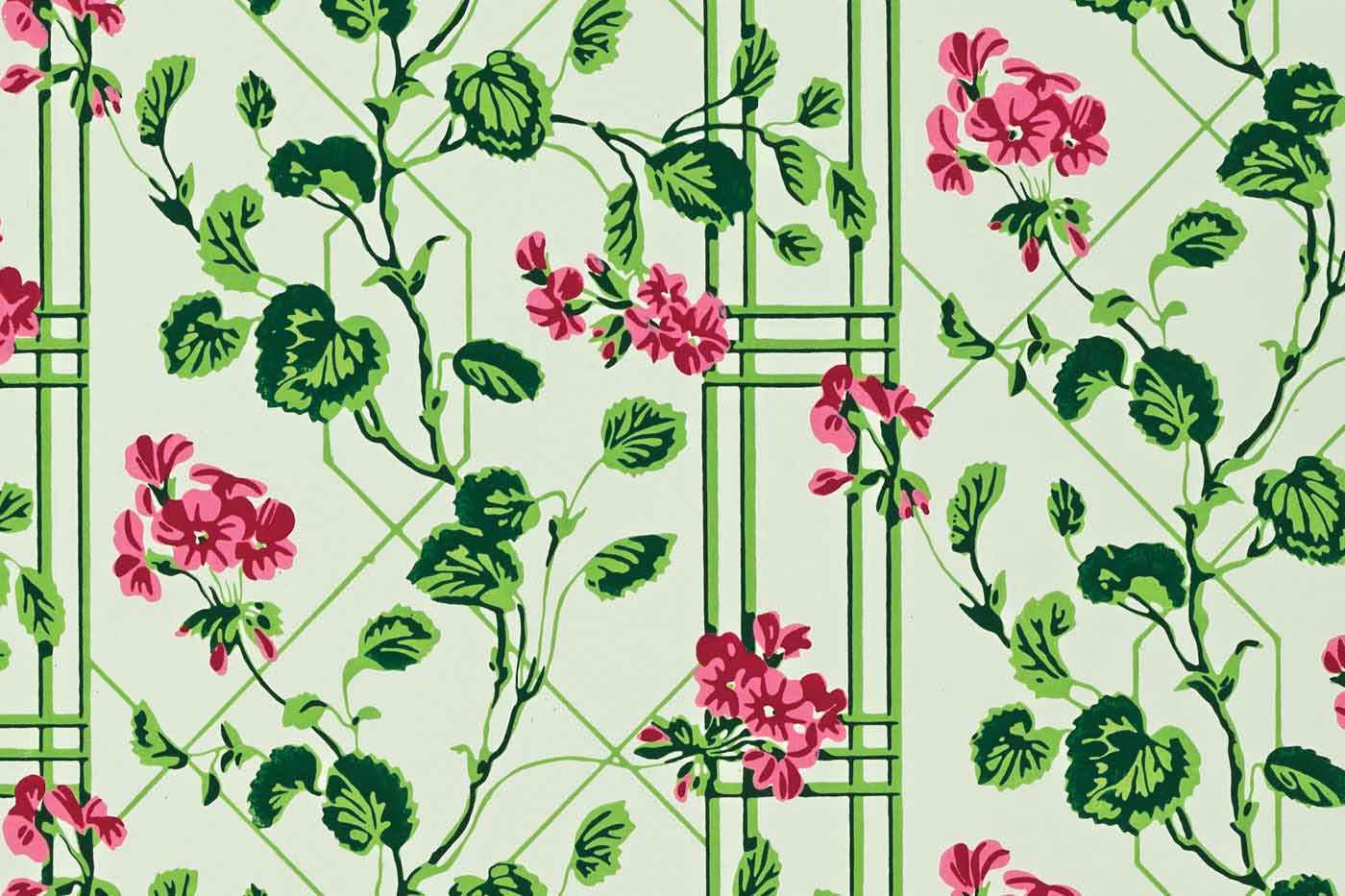

The other new pattern includes a geranium with lattice bamboo, a style that Campbell described as a British take on chinoiserie — an imitation of Chinese motifs. The paper, which lined a trunk, was made of rags and not acidic wood pulp, and such samples tend to be better preserved.

Kirsten Moffitt, the conservator and materials analyst for the Division of Museums, Preservation and Historic Resources, said seams often protect the papers, offering good opportunities for color matching. To identify the pigments present, advanced techniques such as X-ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy and microscopy are applied. She found an ultramarine blue in the lattice design, which helped her date the paper. That blue pigment was introduced in 1835.

Using X-ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy, which Moffitt described as an instrument that looks like a ray gun, she can use beams of X-ray energy to determine the elements that are present and the pigments that might have been used to create the color.

“I can point the nose of the instrument at what I’m analyzing and pull the trigger. A beam of X-ray energy comes out and interacts with all the little atoms,” she said. “They give off their own kind of energy, which produces a spectrum on the screen. I can see where the peak shows up, and I can see I’ve got copper, I’ve got lead, I’ve got arsenic, I’ve got calcium.

“Then I can look at a sample under the microscope. Each pigment has its own distinct characteristics when viewed under the microscope, so this helps me refine the elemental information.”

The challenges of reproducing 18th-century wallpaper patterns can be complicated by the fact that some samples are so small that they do not show the full pattern.

“Ideally, we like to have a full repeat of the pattern,” Larson said. “Sometimes you can make an educated guess on the pattern, but sometimes there’s not enough information.”

And that is why the collaboration is so important. The process becomes a marriage of scientific analysis and knowledge of both tastes and methods of the time.

Gifts to the Helmer Endowment Fund support Colonial Williamsburg’s historic interior authenticity efforts, including wallpaper research.