Back to Sewing Basics

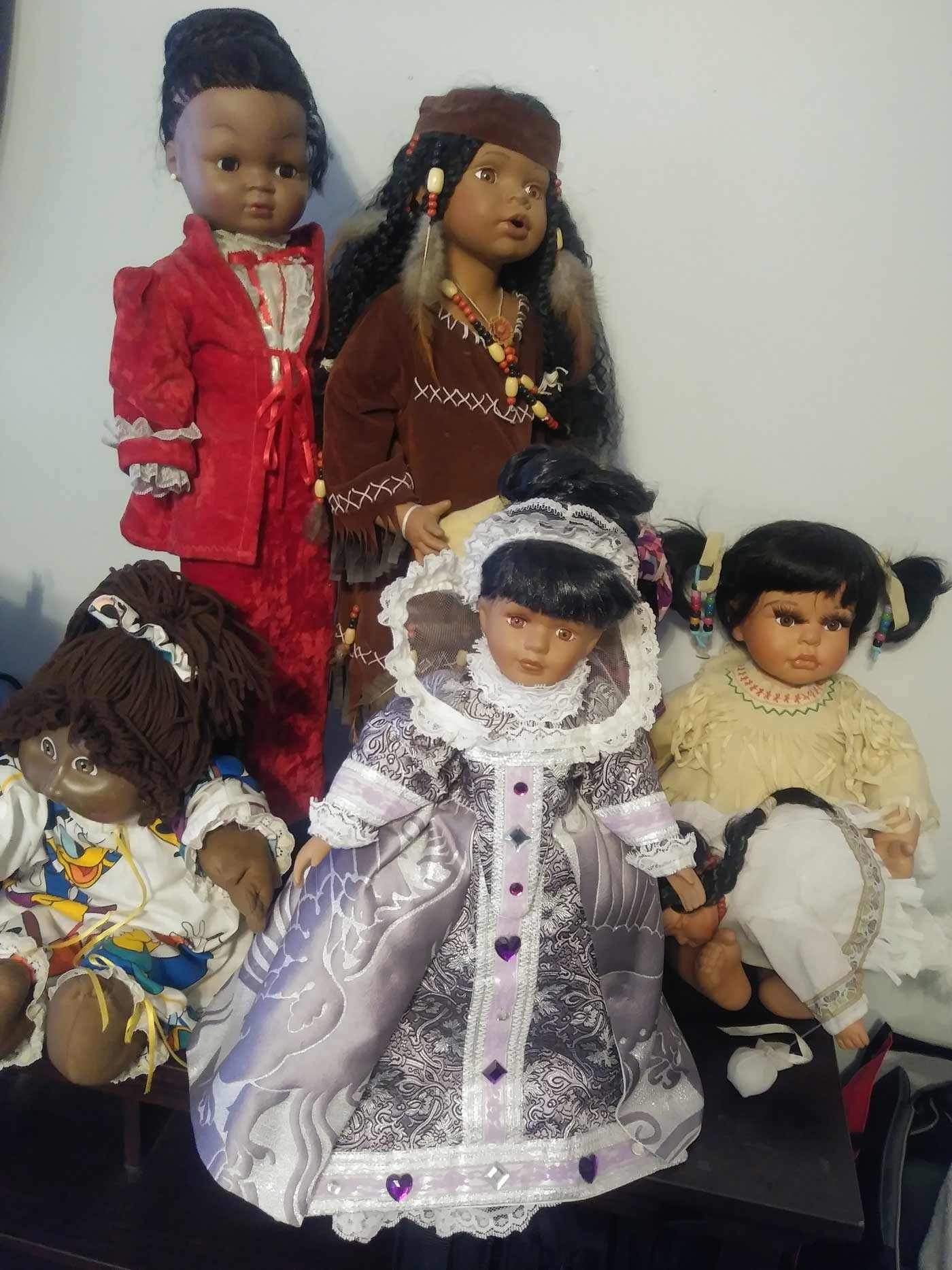

In the interpretation of slave narratives, we often use a variety of props or objects to enhance the story. Sometimes that is a doll or two which can be seen throughout our programs. One of the women I portray is an enslaved woman named “Betty” who was the cook at Peyton and Elizabeth Randolph’s house in Williamsburg. For the program “My Story, My Voice,” I created dolls to use when portraying her as a five-year-old girl. When transitioning her into adulthood, her doll (a second doll) has succumbed to time but is still with her as her constant companion.

I interpret that Betty is not only the cook, but she is also skilled at sewing and makes dolls mostly for the enslaved children on the property to boost their spirits through times of sadness. You see, according to slave narratives, enslaved children begin their lives playing and growing up alongside all the children on the property, including white children, until they are about 7 or 8 years old. It is around that time they are separated from their counterparts and informed that they are slaves and must begin their work. I’d imagine that the dolls would give them a bit of comfort at such a daunting and confusing time.

When I interpret on Duke of Gloucester Street, you will most times find Betty sitting on a bench sewing dolls. Having this skill along with being a fine cook is why she is valued at 100 pounds, which in the 18th century was a great deal of money. The more skilled an enslaved person was, the more valuable they were to their owners. For instance, the York County Wills and Inventory recorded on July 15, 1776, that out of the 27 enslaved people owned by the Randolphs, there were only four valued at that high of a price.

One day, I was out on Duke of Gloucester Street when a family I knew came to hear me interpret. They had a little girl with them, around 10 or 11 years old and although she listened intently to Betty’s story, she seemed fixated on the little doll I was finishing. When the interpretation was over and she was satisfied with her answered questions, I asked her if she would like to have the doll. She answered yes and I gave it to her. Several weeks later, my friend called me and thanked me for my generosity. She also wanted to let me know that the little girl never played with dolls but cherishes the one I gave her.

As “Succordia,” another enslaved woman I portray from the Randolph house, there are dolls on the mantle of the room I perform in. I interpret that Betty made them for her, and they represent the two elders on the property. In our program “What Holds the Future,” a dramatization of enslaved servants right before they are auctioned off, Pheby realizes that she needs to get her baby’s doll back to her before she is sold off. Another of my colleagues, Roger, also uses a doll in his interpretation.

As for me, like Betty, dolls have always been my constant companion. My mother was sort of a gypsy, so we moved a lot which meant we lost a lot. But when I got to high school and took a Home Economics class that included sewing, I learned how to create things that I could take with me wherever we went.

So, in this time of self-quarantine, I’ve found it cathartic to take a little time to get back to basics, reminding myself of one of the ways we survived without the modern technologies we rely on so much today. I encourage you to find an old sock and let your imagination speak to you and see what you might create.

The tools you will need to make the larger doll are as follows:

Sock

Scissors

Needle and Thread

Cotton balls (stuffing)

Cotton fabric

For the little doll you will need:

A rock for the head

Cotton Fabric

Bias tape

Needle and thread

The only skill I used for this project was knowing how to straight and whip stitch. I was blessed with the ability to cut free hand, so I don’t use a pattern, I just let my creativity take me where it wants to go.

Margarette Joyner says she is an elder interpreter at the Foundation. “It is my honor to give voice to the voiceless. I enjoy sewing, singing, collaging, making jewelry and all aspects of theatre. I also enjoy working in my yard and decorating of all kind. What brings me peace is, like Succordia would say, ‘God’s grace and his mercy.’ ”