The Friends (And Enemies) of George Wythe

So, you think you know George Wythe? Hey, I get it. A few months ago, you read my Wythe 101 blog post. Mulling over the exquisite verbal craftsmanship contained within its 1,616 words, your confidence soars. “I’m giddy with knowledge,” you tell yourself, “I know practically everything about the venerable George Wythe, tutor of Thomas Jefferson, Master of Light and Shadow, Manipulator of Magical Delights, Devourer of Chaos, Champion of the Great Halls of Tarr’akkas!” Well, first of all, aside from the Jefferson part, you have confused George Wythe with Usidore the Blue, a fictional wizard from the podcast “Hello From The Magic Tavern.” And second, I beg you to recall the previous blog was titled, “Wythe 101.” We’ve barely scratched the surface on this titan of early America! So buckle up, buttercups, as we hit 88 miles per hour to learn three random, fun facts about the friends (and enemies) of one of the most influential Virginians to have ever lived, George Wythe.

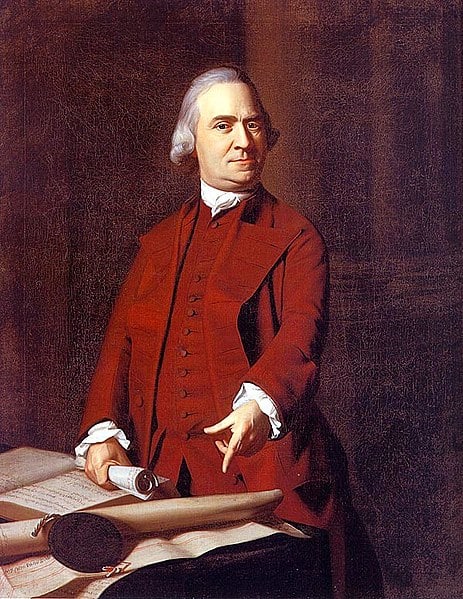

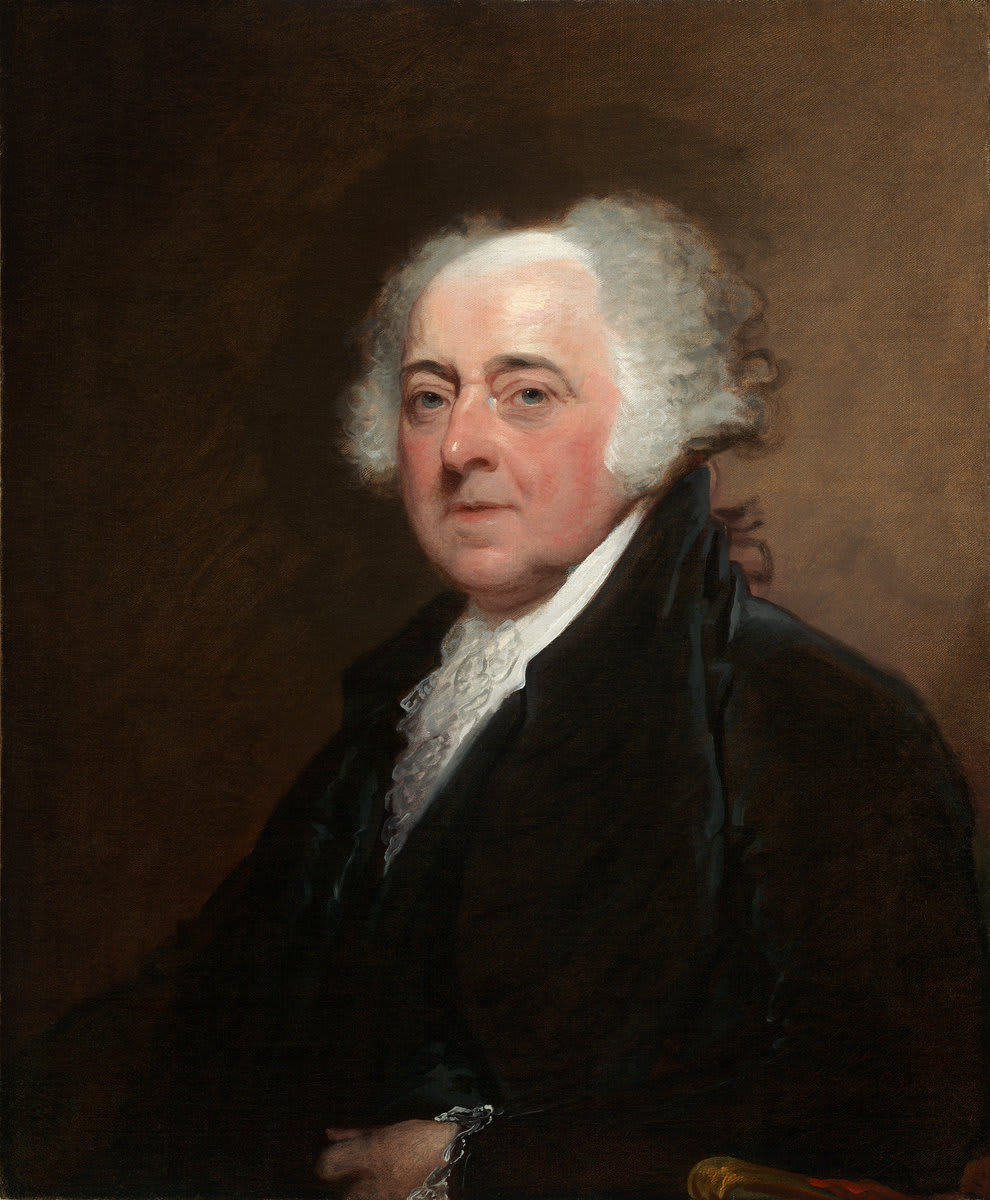

1: George Wythe Was Pals with John and Sam Adams

As you already know from the first blog, Mr. Wythe’s name appears at the top of the Virginia Delegation on the Declaration of Independence, and was an early proponent for the Continental Congress to make the motion. It should not come as any surprise, then, that he spent a good deal of his time in Philadelphia with some of the top men in favor of the cause, to include Samuel and John Adams. Thanks to some surviving letters, we can catch a glimpse of what these men were doing with their spare time in the city, and how much they missed each other afterward. Wythe writes to Sam Adams in August 1778,

“tell me what more you would say if we were eating a saturday's dinner at mrs Yard's, smoaking [sic] a pipe in the political club at the Indian queen—holding a tete' a tete' at my apartment opposite to Israels garden—or rambling toward Kensington.”

And then to John Adams in December 1783,

“Your letter, therefore, by mr Mazzei, delivered to me today, this day, by which I learn your wish to receive a line from me, and that too wherever you be, was received with joy. I accept the invitation with a pleasure one feels in renewing an acquaintance with an old friend whose company was entertaining and improving.”

Even by these brief snippets, it is easy to see Mr. Wythe had a great affection for the Adamses and thought of them frequently, even after the Cause for Independence was won.

2: George Wythe Had At Least One Powerful Enemy

And I mean very powerful. I’m talking about John Murray, Fourth Earl of Dunmore, His Majesty’s Viceroy and Lord Governor of Virginia. Sometimes better known simply as Lord Dunmore. On the surface, this might seem obvious. Afterall, we’ve noted already that Mr. Wythe was an early proponent of independence; it stands to reason, then, that he would be at odds with the Royal Governor during such a season. However, the previous governor, Francis Fauquier was a very good friend of Wythe. In fact, Governor Fauquier, who was a member of the Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, often enjoyed the company of Mr. Wythe alongside the young Thomas Jefferson and William Small, professor of moral philosophy at William & Mary. Together, they formed what Jefferson would call a “partie quarree,” where the four would gather and presumably enjoy discussions on moral and natural philosophy. John Murry, a.k.a. Lord Dunmore, however, did not hold the same esteem in Wythe’s eyes. The two had an infamous altercation described in the prologue from a 19th century edition of Judge Wythe’s Decisions of Cases in Virginia by the High Court of Chancery:

“One day, in the General Court, over which Governor Dunmore then presided, Mr. Wythe and Mr. [Robert Carter] Nicholas were engaged on one side of a cause; Mr. [Edmund] Pendleton and Mr. [George] Mason on the other. The case being called, Mr. Wythe urged the trial of it; Mr. Pendleton wished it continued, as Mr. Mason was absent, and there were two counsel on the other side. Lord Dunmore had the indelicacy to say to Mr. Pendleton, "Go on, sir, for you'll be a match for both of them." "With your Lordship's assistance," retorted Mr. Wythe, sarcastically, but at the same time bowing politely. The spectators enjoyed the rebuke, so keenly and politely administered.”

Indeed, by 1775, George Wythe’s relationship with Dunmore had deteriorated to such a degree, he spoke openly at the Continental Congress in favor of seizing the various governors of the individual colonies, noting on 6 October:

“It was from a reverence for this congress that the convention of Virginia neglected to arrest Lord Dunmore…”

I dare not speculate on Mr. Wythe’s implications here, but you, dear reader, are more than welcome to draw your own conclusions.

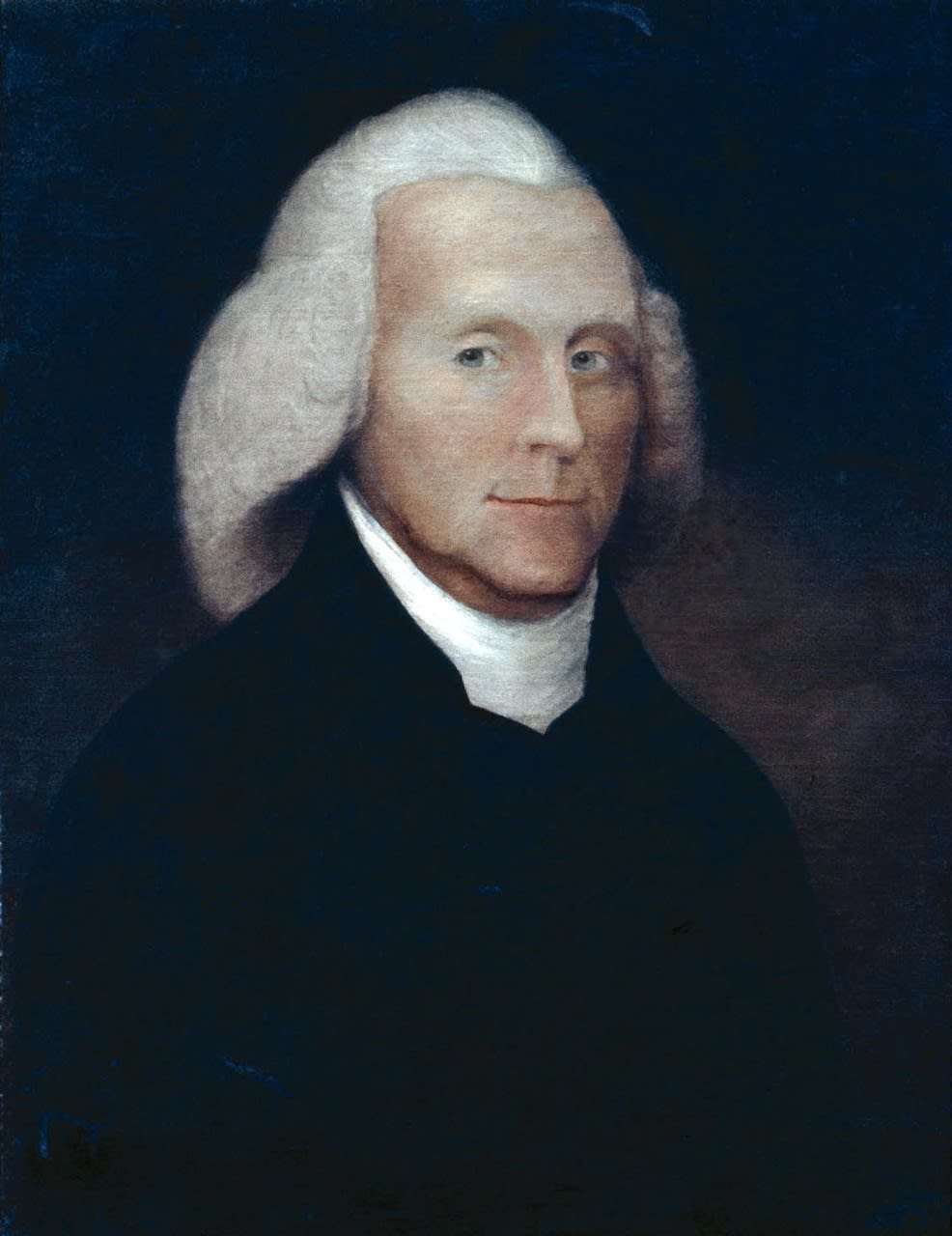

3: George Wythe Had a Career-long Frenemy

Don’t act so surprised. We’ve all got at least one person in our lives who we would consider to be a friend… that we absolutely cannot stand. Maybe it’s the way they sound or talk, or maybe they annoy you. No matter the reason, you’ve got a frenemy, and while he might not have used the same term, so did George Wythe. His name was Edmund Pendleton.

From what I can tell, Wythe’s rivalry with Pendleton stemmed from Wythe’s days arguing before the General Court in Williamsburg. George Wythe was highly educated, thorough, and meticulous to the point of pedantry in the courtroom. His arguments have been noted as incredibly dense and laden with references that only the most versatile scholar could follow. His quotations in the languages of Cicero and Homer were a far cry from the work of Mr. Pendleton, who, though considerably less-educated than his rival, was considered by Jefferson to be, “the ablest man in debate I have ever met.” Another of Wythe’s students, Henry Clay, gave us not only a clear image of how this rivalry often played out, but also how other people viewed the two contestants when he said,

“On one occasion, when Mr. Wythe, being opposed to Mr. Pendleton, lost a case, in a moment of vexation he declared, in the presence of a friend, that he would quit the bar, go home, take orders, and enter the pulpit. You had better not do that replied his friend; for if you do, Mr. Pendleton will go home, take orders, and enter the pulpit too, and beat you there.”

As you probably guessed, this rivalry was too good to fizzle by a silly Revolution. In 1776, the Virginia Legislature formed a committee to revise the laws of the new Commonwealth. Both Wythe and Pendleton (along with Jefferson) were part of this committee, and the stout traditionalist Pendleton often butted heads with the more progressive Wythe. In 1778, Wythe was named an associate justice to the High Court of Chancery, and of course Edmund Pendleton was not only placed on the court alongside, but took the position of Chief Justice. Perhaps a little irritating, but on March 3, 1789, Pendleton wrote a brief letter to Judge Wythe to inform him,

“I yesterday afternoon signified to the Governor in writing a formal resignation of my Office as one of the Judges of the High Court of Chancery.”

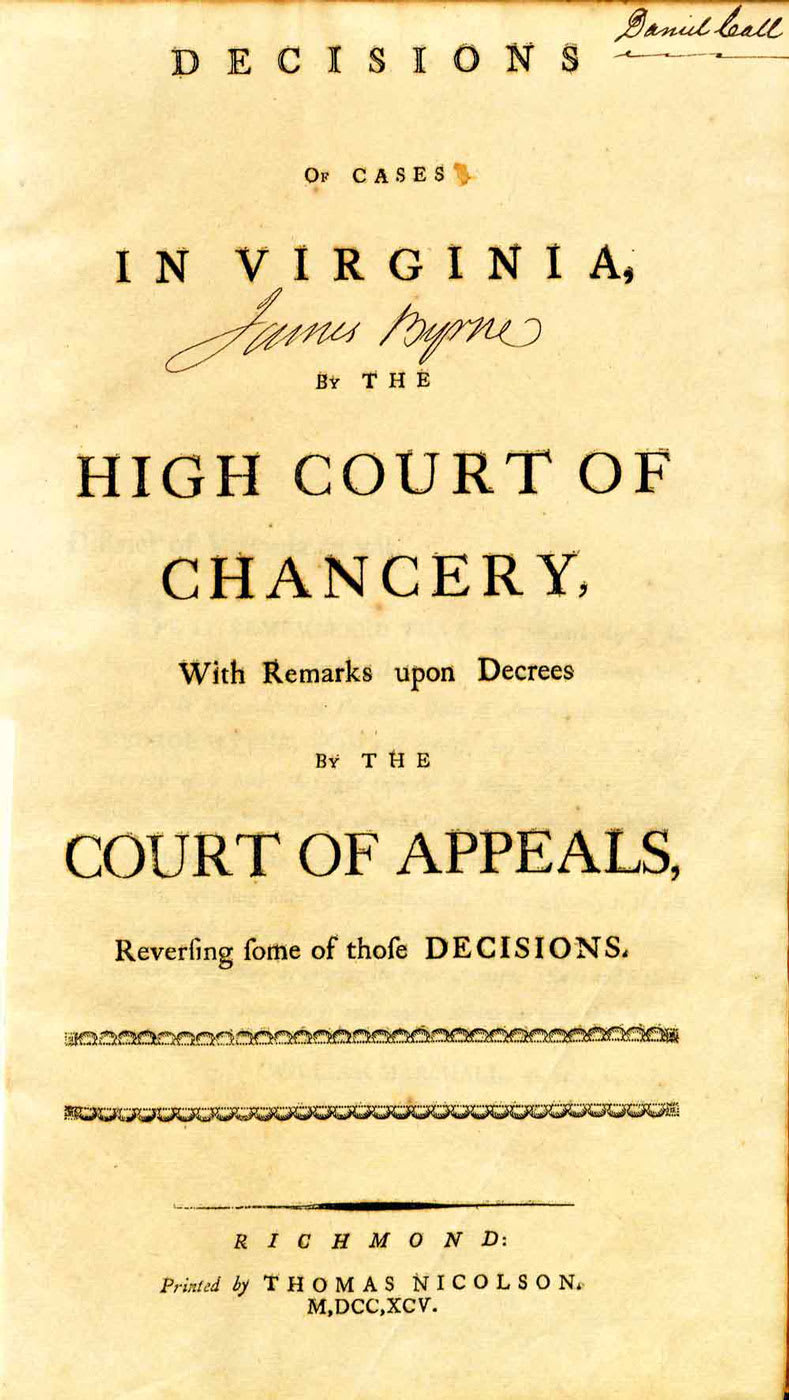

Now, you may be thinking this would offer Chancellor Wythe some relief from the rivalry, but, alas, Judge Pendleton offered his resignation to the High Chancery Court because of an advancement. He was resigning his position in the Chancery to take a seat on the Court of Appeals, and it is here where Wythe’s irritation reached fever pitch. Over the following 14 years, Pendleton’s superior court constantly overturned Chancellor Wythe’s rulings. Pendleton overturned so many of the High Chancery Court’s judgments that George Wythe did something that only George Wythe would do: he wrote a book about it.

Here’s the thing, though. Unlike Wythe’s relationship with Dunmore, in the many hours I’ve read Wythe’s letters and people’s impressions about the relationship with Pendleton, I’ve never once gotten the impression that these men hated each other. They weren’t enemies; they were rivals- frenemies, if you will. In 1776 when Wythe writes to Pendleton concerning the Committee for the Revisal of the Laws, Wythe closes the letter by stating he has, “...most profound respect…” for Mr. Pendleton. Indeed, despite the fact that one could argue Pendleton overturned Wythe’s rulings to his dying breath (a story for another day), when Edmund Pendleton died in 1803, one of the pall bearers at the funeral was none other than George Wythe.

Sometimes when we think about people of the past, we like to tuck them into neat little categories. Often, we make the mistake of thinking they all behaved or thought one way or the other. But even with these few examples, we can see clearly that the often touted “Venerable George Wythe,” held differing opinions regarding different people. Despite being known for his disinterested (fair and balanced) nature on the bench, the relationships George Wythe had with the gentlemen named in this blog give us a clearer understanding of his personal nature, his like, dislikes, and (in the case of Dunmore) his limits. I hope you enjoyed our foray into the life of Chancellor Wythe. Until next time, dear reader!

Robert Weathers has been working as a first-person interpreter at Colonial Williamsburg since January 2008 and premiers this fall as Nation Builder George Wythe. When he is not in breeches, he can often be found wearing shorts no matter the weather, and riding roller coasters with his wife Kaitlyn.

Learn More

Related Events

-

Performance: Washington's Road to Revolution

Join George Washington before he leaves for Congress in 1774 to learn about how the year’s events affected life both publicly and privately on the Road to Revolution.

Art Museums Admission

-

Performance: Visit with Marquis de Lafayette

Step into the past with the Marquis de Lafayette, French hero of two worlds. Through stories and questions, explore the hopes, choices, and challenges he faced.

CW Admission

-

Performance: Nation Builders Discuss Slavery

Join two Nation Builders to discuss how they viewed the complicated tragedy that was the institution of slavery.

Art Museums Admission