My name is Tamara Eichelberger, and I am one of the field technicians excavating at Custis Square. Although there are many people who live on the site after John Custis IV, I chose to focus my research specifically on Dr. James McClurg because the standing kitchen on the property has been named after him. We know very little about who McClurg was and what he did on the site, however. I am hoping my research on McClurg will help us better understand our finds from the field.

Call the Doctor

The first thing many guests notice when they walk onto the Custis Square archaeological site is the small brick kitchen sitting towards the East of the property. Formerly known as “Martha’s Kitchen,” archaeology and research have shown that this is not a kitchen that belonged to Martha Washington. It did not even belong to John Custis IV. Built on top of the original 18th-century kitchen foundations, this building was constructed by a man named Dr. James McClurg. Now known as the “McClurg Kitchen,” it was thought to be constructed sometime in the early 19th century.

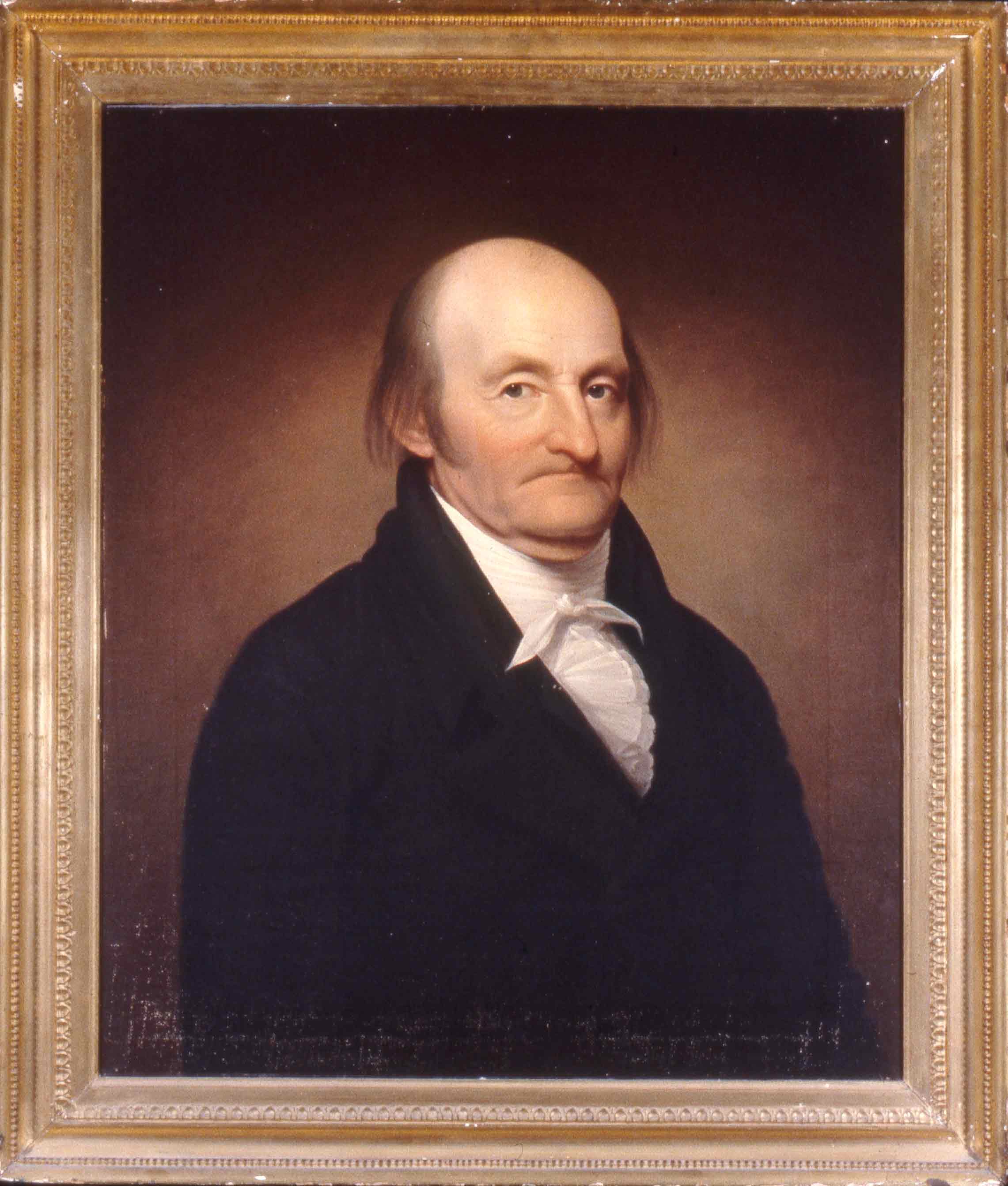

The name “McClurg” does not often get much recognition among visitors to the site. Most of us on the crew at Custis Square (including myself) did not recognize the name either. Despite his lack of recognition, Dr. James McClurg was a well-known physician in Virginia during the late 18th century and early 19th century. He was a professor at the College of William and Mary and in correspondence with many well-known figures in Williamsburg: St. George Tucker, Thomas Jefferson, and George Wythe. McClurg was even a delegate for part of the Congress of the Confederation and mayor of Richmond for three, year-long terms. Although his name is not as recognizable as Jefferson or Wythe, McClurg played a role in American and Virginia history. He also was a resident at Custis Square during the late 18th century.

What did McClurg do on the site?

The focus of my project is to understand who Dr. James McClurg was and to understand what he was doing while residing in Williamsburg, especially as it relates to the Custis Square Property. As the standing kitchen on Custis Square is attributed to McClurg, there may have been other construction while he was living on the property. He no doubt was purchasing goods in town and corresponding with many people. Having an idea of who McClurg was can give us an understanding of what he was doing in Williamsburg, what kind of work was done at Custis Square, and the kinds of material goods he might have owned.

Through my research, I’ve also discovered that James McClurg was not the only resident on Custis Square while in Williamsburg. He married Elizabeth Selden in 1779 and had at least one child (Elizabeth Selden McClurg Wickham) with her. McClurg also owned enslaved individuals while on the property whose lives are unknown. While the focus of my project relates primarily to McClurg, these residents may also have played a roll in shaping Custis Square.

In order to learn more about McClurg, I have been diving into the primary sources related to him: the newspapers, his surviving letters and correspondences, surviving letters and records written about him, and ledgers from businessmen in town. There are many second-hand accounts written about McClurg as well which help to paint a better picture. Unfortunately, there are gaps in the records as some primary documents were destroyed in Richmond during the Civil War. The archaeological record may also help uncover more information about McClurg. Several deposits within the wells on the property date to the time period of McClurg’s ownership and may offer even more clues to his life in Williamsburg.

Early Life in Williamsburg and Abroad

McClurg was born in 1746 in the Hampton area to Dr. Walter McClurg, a British naval surgeon who worked there at the time. His mother is not known, however. McClurg attended William and Mary until 1762 for his formal education. During his time at William and Mary, he met Thomas Jefferson, who also studied at the college that time. They became friends during this time and later correspondences. Although Wyndham Blanton, who wrote an extensive book on medicine in Virginia during the 18th century, praises McClurg for his achievements in learning there, the William and Mary Quarterly tells of McClurg’s temporary suspension for “injurious behavior” towards residents in the town. Whatever crime McClurg may have committed, he was eventually forgiven, his reputation was not harmed, and he was able to complete his education.

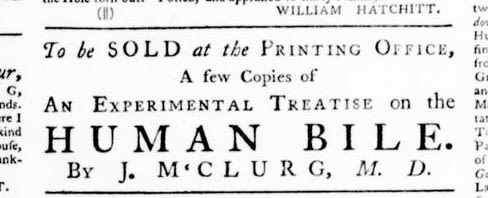

After he finished at William and Mary, McClurg traveled abroad to Europe. His first stop was the University of Edinburgh. McClurg received his medical training as a physician here, as did may other Virginia physicians. McClurg finished his time at Edinburgh in 1770 with a thesis titled “De Calore” and then traveled to Paris and London to continue his studies into medicine and surgery. He produced his most famous work during that time in Paris and London: “Experiments on the Human Bile and Reflections on the Biliary Secretions.” After this publication in 1772, McClurg made his way back toward his home in Virginia.

A Member of Society in Williamsburg

James McClurg returned to Williamsburg by 1773. His exact travels in the state are not very clear, but the first sign of him in Williamsburg was an advertisement in Purdie and Dixon’s Virginia Gazette. In the May 27 and June 3 editions, McClurg posted an advertisement for the sale of a few copies his “Experiments on the Human Bile.” Although the evidence points to McClurg living in Williamsburg at this time, it is still unclear where in town he might have resided for the early part of his time in the city.

McClurg quickly became a part of society in Williamsburg and joined many different organizations. One of the first he joined was the Free Masons. His first listed meeting was on August 21, 1773. McClurg was passed and raised in the Masons on Dec. 22, 1774 and was elected as a senior warden in 1777. He was appointed Junior Warden of the Stewards Lodge at the first Grand Lodge in 1778 and was a delegate from Williamsburg Lodge in Grand Lodge on Oct 28, 1785. McClurg also became a member of the Virginia Society for the Promotion of Useful Knowledge, which was founded in 1773 and lasted until around the time of the Revolutionary War. It is clear from his memberships to these organizations that McClurg was becoming a prominent figure in Williamsburg, especially among the well-educated men of the time. He also created some close connections through these groups.

Practice of Medicine

While living in Williamsburg, McClurg chose to practice medicine strictly as a physician, diagnosing patients and prescribing treatment. When the Revolutionary War breaks out, McClurg offered his service to the Continental Army. When he hears of a position for a physician for the army, he wrote to his friend Thomas Jefferson on April 6th, 1776:

If this should find you at Congress, when the business it relates to is undetermined, I hope you will use your Influence in favor of your humble Servant. It is believ’d here that a Physician will be appointed to the Continental Troops in this Colony; an office that I desire Exceedingly, as it would gratify at the same time my passion for Improvement in the profession I am destined to, and my zeal to do my Country some Service. In this time of general activity, I do not like to be an idle Spectator; and I know not any post which would suit me so well.

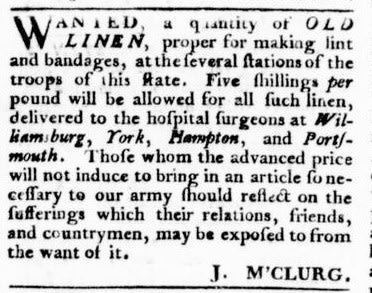

Although Jefferson and others supported the nomination of McClurg, unfortunately, another man was given the post. McClurg still worked for the military hospitals as a surgeon in Hampton, however. During that time, the situation become somewhat dire for the workers at the hospitals. McClurg placed an ad in the September 5, 1777 edition of Purdie’s Virginia Gazette for old linen to use as bandages at the hospitals in Williamsburg, York, Hampton, and Portsmouth. The issue of pay became a prominent complaint as well. McClurg applied to the governor and Council in Virginia in 1779 for higher pay and rations for those working in as surgeons at the Virginia Hospitals.

While working as a surgeon in the army, James McClurg was given the post of the first Professor of Anatomy and Medicine at William and Mary in December 1779 by his friend James Madison. By 1780, he wrote again to his connections in the government, and he was finally promoted to a naval surgeon in Hampton, which provided him a boost in his pay and rations. Near the end of the war in 1781, he may have even been promoted further to the position of physician of the Continental Army (the post to which he originally applied), but his exact title and promotions are not well documented. These higher-ranking positions during the war gave McClurg more fame and recognition. By 1783, McClurg left the position of Professor of Anatomy and Medicine as he moved to Richmond. As he was occupied for much of his professorship by the Revolutionary War, it is unclear how much he taught while in his position as professor. The post was not filled after he left the school.

Purchase of Custis Square

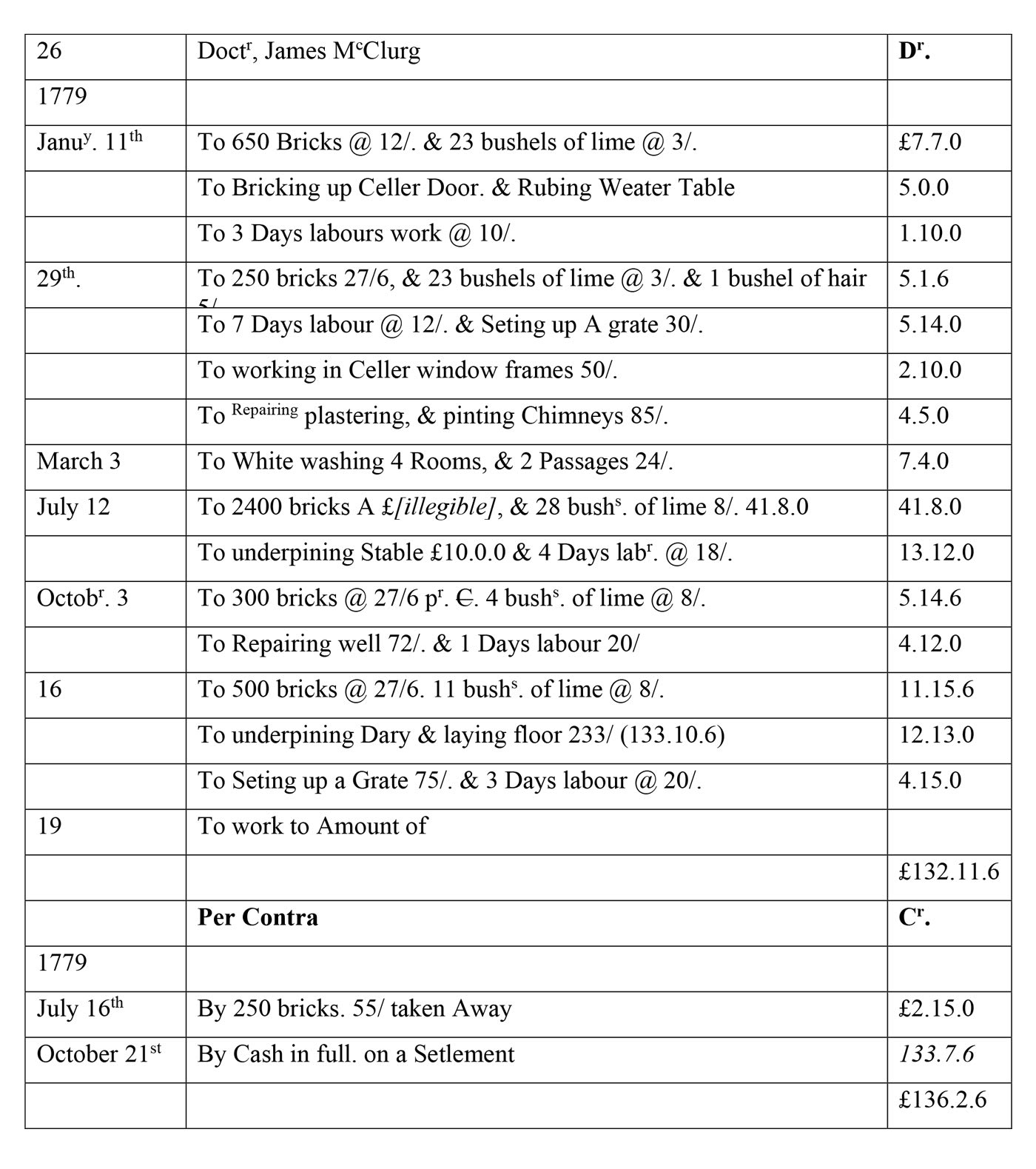

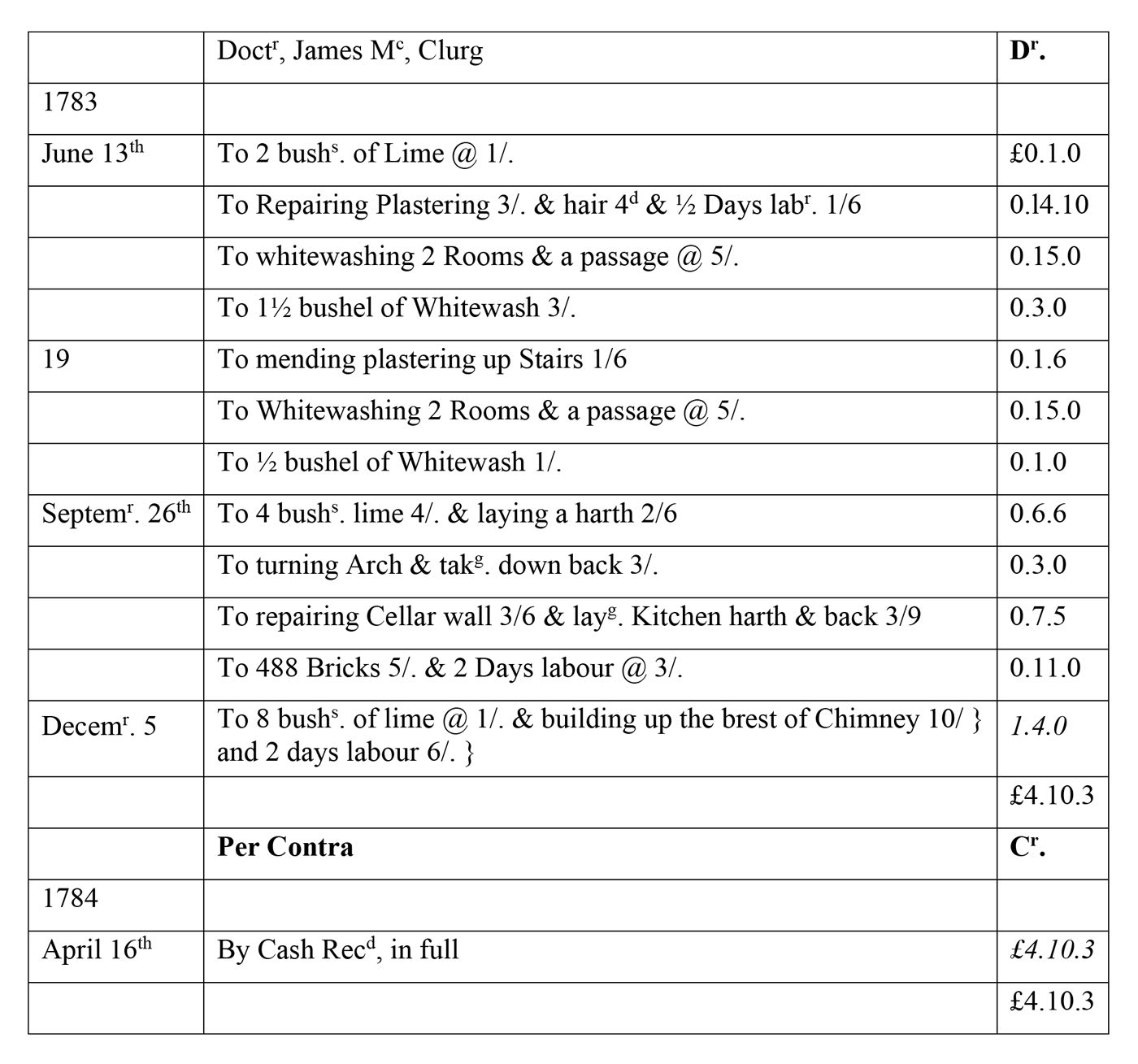

McClurg did not officially own Custis Square until 1779. Some previous research by Mary Stephenson and archaeologist Patricia Samford suggests that he may have rented the place as early as 1774 or 1775. When John Parke Custis wrote of the lot in 1778, however, he described it as not being fit for living. He sold the lot by December and McClurg most likely bought it by January of 1779. The Humphrey Harwood Ledgers show that during this year, several repairs were done to the property throughout the year:

These repairs were probably necessary if the property fell into disrepair, as suggested by John Parke Custis.

While he lived at Custis Square, McClurg married a woman named Elizabeth Selden who was from Hampton. Their marriage was announced in the Virginia Gazette, but with little detail. They had a child together in 1781 who was named Elizabeth Selden McClurg.

Near the end of the Revolutionary War, the British Army came near Williamsburg, and there were reports of disease and destruction. St. George Tucker described some of the misfortunes in a letter to his wife dating July 11, 1781:

Our friend Madison and his lady (they have lost their son) were turned out of their house to make room for Lord Cornwallis. Happily the College afforded them an asylum. They were refused the small privilege of drawing water from their own well. A contemptuous treatment, with the danger of starving were the only evils which he recounted, as none of his servants left him. The case was otherwise with Mr. McClurg. He has one small servant left, and but two girls. He feeds and saddles his own horse and is philosopher enough to enjoy the good that springs from the absence of the British without repining at what he lost by them.

Although this letter only describes McClurg’s enslaved people leaving him, there is a hint that he may have lost more. In 1783, McClurg was listed once again in the ledgers of Humphrey Harwood:

Researcher Mary Stephenson suggest these repairs were ordered due to damages that may have been caused by the British. I also think these repairs may also have been needed to fix the place for rental, which Stephenson believes he did after moving to Richmond in 1783. Land tax records show that McClurg still owned Custis Square up until 1811 when it was sold to Samuel Tyler. During this long stretch of time, it only makes sense for McClurg to rent the property, especially if he is still being taxed for the land. The information of to whom he may have rented Custis Square has been lost during the Civil War which destroyed the Williamsburg and James City County records.

McClurg’s Later Life

Both in 1779 and 1780, McClurg wrote to his connections about his lack of pay while working as a surgeon. This lack of pay seems to have influenced McClurg’s switch towards a life of politics. A letter written to Thomas Jefferson on May 17, 1781 suggests that Jefferson attempted to persuade McClurg to study the law. McClurg’s response clearly shows that he entertained the idea of switching careers at that point in his life. The pay of his profession continued to be a problem for McClurg after his move to Richmond. He wrote to Jefferson again in 1784 of how desirable a position in the government would be as his profession as a physician was tiresome and not very profitable. This may be the reason McClurg joined the Virginia delegation at the Congress of the Confederation. Despite his complaints on his lack of money, in 1783 McClurg is recorded to have “5 slaves, 2 horses and 2 cattle" and in 1784 he has "7 slaves 2 horses, 3 cattle and 2 wheels.” Although probably not as wealthy as some of his contemporaries, it is clear McClurg still made a decent living for himself.

McClurg continued his life as both a renowned physician and politician. He was a member of the Virginia delegation to the Congress of the Confederation, which created the Constitution (although he left in 1787 before signing). He also became the Mayor of Richmond in 1797, 1800, and 1803. McClurg continued to practice medicine while in Richmond. He was appointed president of the Medical Society of Virginia in 1820. McClurg died in 1823 and was buried at St. John’s Episcopal Churchyard in Richmond.

Future Research

Although I have found several primary sources regarding McClurg already, I hope to dig even deeper into the life of McClurg. I especially want to search different inventories and other primary documents from the time McClurg lives in Williamsburg. I also hope to do more research into the finds from the 1960s excavations of Custis Square. The excavated wells contain materials dating to McClurg’s time period at Custis Square. Using this information can help to determine more about McClurg and his family and the enslaved who lived on the property. It may also help me learn more about the possible later tenants who may have been on Custis Square.

Tamara Eichelberger is an Archaeological Field Technician for the Custis Project. She has a Master’s in Human Osteology and Funerary Archaeology (that’s human skeletons and remains!) and has worked at the Colonial Williamsburg Kids’ Dig!