The discovery and examination of the Williamsburg Bray School has been an important and exciting project for William & Mary and the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation (CW), particularly CW’s Department of Architectural Preservation and Research, working in collaboration with the Department of Conservation.

Our team of specialists includes architectural historians, preservationists, and conservation scientists working together to explore and understand the buildings in our care, and the Bray-Digges House, which housed the Williamsburg Bray School, an 18th-century institution dedicated to the education of enslaved and free black children, will be no exception. In fact, efforts are underway already and various methods are currently being used to investigate this building with its complex and unique history, and you can read more about that here. This post will discuss the contribution that paint analysis has made to the research thus far.

Paint analysis offers a unique way of learning about the story of a structure through its paint layers. The concept behind paint analysis is simple: by collecting a small sample of paint from a painted surface, carefully slicing the chip of paint in half, and looking at its cross-section with a high-powered microscope, one can see the number and nature of coatings applied through time, ideally from the original period (at the bottom) to the current paint (at the top).

In addition to allowing us to see the earliest finishes, the comparison of paint layers found on different elements like doors and cornices allows us to see which might be original (having the most paint), and which might have been added later (having the least paint). With additional analysis using dedicated scientific instruments, the presence of certain pigments with known dates of introduction can be another important clue for dating. For instance, the pigment zinc white (a zinc oxide, or ZnO) was not introduced until the mid-19th century. Therefore, the presence of zinc in a layer tells us that paint cannot be any earlier than c.1850

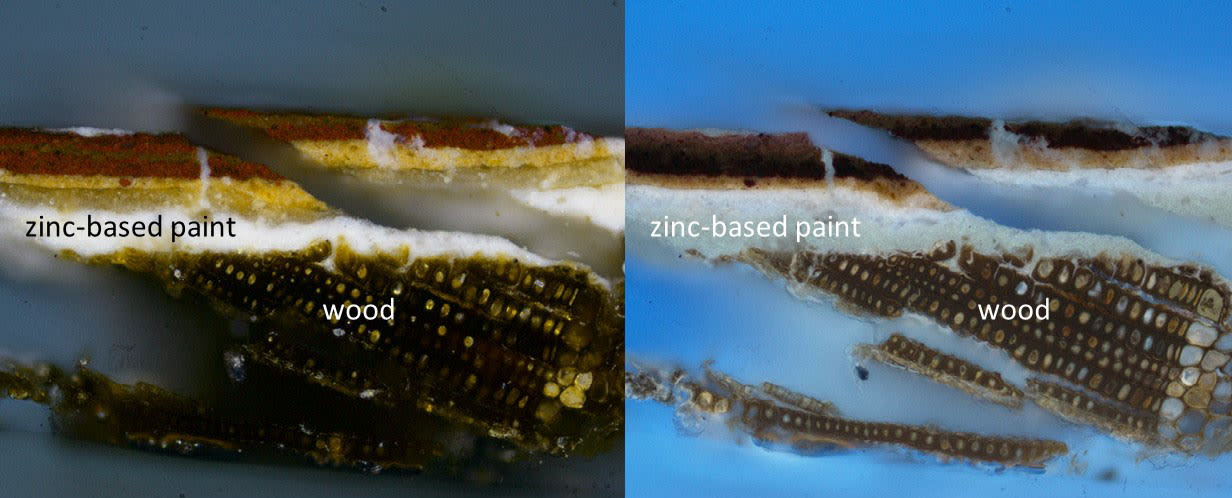

Paint analysis of samples from the Bray School were collected and analyzed in 2017, and another group of samples were collected and analyzed in 2020-2021, in CW’s Materials Analysis Laboratory. The paints suggest that much of the interior woodwork in the building dates to the mid-19th century. We know this because the first paint layer on these elements contained zinc white pigment, which has a distinct light blue, ‘twinkling’ appearance under the microscope when exposed to ultraviolet (UV) light. The presence of zinc was confirmed with another technique called scanning electron microscopy-energy dispersive spectroscopy (SEM-EDS).

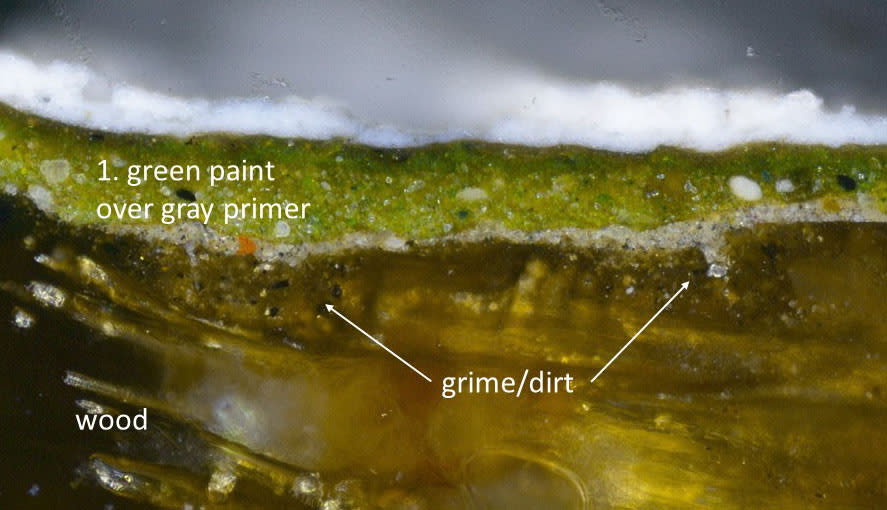

The paint analysis suggests that only a few elements are ‘early’, or at least, ‘older’ than the rest. These elements include: the stair newel, a paneled door re-used as wainscot in the first-floor lobby, and window trim in the first-floor east and west rooms. These elements all share the same early layers, starting with a gray primer and a green paint. However, this green paint contains the pigment chrome yellow (PbCrO4), which did not come into general use until the early 19th century.

Therefore, this paint post-dates the Bray School period. Sadly, it seems that none of the Bray School finishes survived.

But a clue popped up that couldn’t be ignored. In a few samples, a layer of grime was visible underneath the green paint.

The existence of grime and dirt here suggests that these early elements might have originally been unpainted - and exposed to wear and soiling - before they were eventually painted with the green paint in the early 19th century.

The Bray School project is a unique example of how paint analysis contributes to our understanding of a building’s history, and that paint isn’t always the only evidence worth considering. Sometimes it is the grime, the cracks, the damage; the various traces left behind by the people who lived, worked, and learned in a building that tells the story. The investigation continues at the Bray School, and we will keep you updated on any new discoveries!

Kirsten Moffitt holds an M.S. from the Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation, where she specialized in the conservation and analysis of painted surfaces. She is the Materials Analyst for the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation’s Conservation Department, and is responsible for the analysis of collection materials including metals, ceramics, textiles, furniture and architectural finishes such as paints, limewashes, and wallpapers. She specializes in historic paint materials and technology, and she shares her research through lectures and publications, both within the field and to the general public. Kirsten truly loves watching paint dry, and her analytical work contributed to Benjamin Moore’s Williamsburg Collection paint line.

Colonial Williamsburg is the largest living history museum in the world. Witness history brought to life on the charming streets of the colonial capital and explore our newly expanded and updated Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, featuring the nation’s premier folk art collection, plus the best in British and American fine and decorative arts from 1670–1840. Check out sales and special offers and our Official Colonial Williamsburg Hotels to plan your visit.