“Has been subject to running away ever since she was ten years old”

The lives of enslaved women are often viewed through their enslavement, their work, and their suppression and violation within a slave society. They are often viewed as an amorphous group, nameless, faceless, unchanged over 200 years of slavery. Their individual stories obscured by neglect. Few stop to think about these countless women as individuals. Even in the most fundamental sense. What did enslaved women look like? What did they wear? What did their hair look like? What complexion were they? These are questions that we may ask about anyone today and questions that are easily answered by observation, video or camera. But for enslaved women separated from us through time, these questions can be impossible to answer. We do, however, have a resource that gives us that insight into a select group of enslaved women — those who ran away.

There were hundreds of thousands of enslaved women who ran away from 1639, when Massachusetts became the first colony to legalize slavery, to 1865, when the 13th amendment abolished slavery in this country. Many of these women ran to live as free women, to visit family members, or to seek transportation to other areas. When these women “absconded,” their owners would place runaway advertisements in area newspapers. These ads gave the names of the women, the date they ran, and sometimes where they intended to go. But these advertisements also gave very detailed descriptions of these women — what they wore, what their hair looked like, their complexion, etc.

For owners, it was important to be specific and thorough when describing the women that ran. This might help ensure that these women were known, could be noticed, and eventually captured. But for us, these ads describe vivid portraits of each of these women. There are many things that can be gleaned about them from these ads: family and romantic connections, personality traits, skills, what language they spoke. In this post, I will be looking at the clothing and jewelry these women wore or took with them when they ran away as well as descriptions of their hair, how it was styled, texture and color based on runaway ads from 1757 to 1804.

Clothing

“She carried with her several Changes of Apparel”

When Zilpha, a Negro woman from Norwich, Connecticut ran away in 1778, she carried with her “One brown Camblet Gown, almost new; 1 black Tammy ditto; 1 blue and white figured Stuff, ditto; 1 dark coloured Callico ditto, partly worn, 1 striped Linen ditto, almost new; 1 black Callimanco quilt, almost new; 1 flowered Lawn Apron; 1 red Broad cloth Cloak, almost new; 1 brown Camblet Riding-Hood, partly worn; 1 black Satin Bonnet, almost new; with a variety of other articles, consisting of Caps, Handkerchiefs, Shoes, Stockings, Ribbands, &c., &c., &c.”

The amount and variety of clothes she took with her when she ran off was not uncommon. Jenny, from Philadelphia, “took with her a bundle of cloaths, consisting of one light chintz gown, a small figure with red stripes, one dark ditto with a large flower and yellow stripes, seven yards of new stamped linen, a purple flower and stripe, a pink-coloured moreen petticoat, a new black peelong bonnet, a chip hat trimmed with gauze and feathers, four good shifts, two not made up, and two a little worn, four aprons, two white and two check, one pair of blue worsted shoes with white heels. She is very fond of dress, particularly of wearing queen’s night-caps. She had in her shoes a large pair of silver buckles.”

These women likely took their entire wardrobe with them. This wardrobe was likely accumulated over time and it could be made, purchased, traded for, and restyled. This was an area where women commonly asserted authority over themselves. They could also maintain cultural retention and develop new African American customs by repurposed garments. Handkerchiefs were used to tie up hair and men’s shoes, hats and coats were worn by women. Daphne from Fell’s Point, Maryland ran away in a pair of men’s pumps. Lear had a white lawn handkerchief which she wore round her head. Joice wore a “red handkerchief tied round her head.” And Fanny absconded wearing a man’s hat.

Jewelry

“Wears rings on her fingers and bobs in her ears”

When women ran away, in addition to the large quantities of clothes they often took with them, they also took their most valuable possessions. This often included jewelry. For many of the women the jewelry they had did not just hold monetary value, it was of cultural or spiritual importance.

A “new Negro” woman who ran away in New York in July of 1763, had “beads round her Arms and Neck.” “Salt water” slave women Cloe and Candice, along with a 3-year-old boy, Jack, all wore beads when they ran away from Rock Creek, Maryland in 1770.

“New” and “Salt Water” were terms used to describe African born people just coming into the colony. The use of beads by many African peoples is quite common and something that survives through many generations. Evidence survives in slave burial grounds of individuals being interred with beads.

In addition to beads, enslaved women wore or took with them a variety of jewelry. Sarah, from Buckingham County, Virginia “wore two silver rings on her fingers” and Hannah, who ran from Newark, New Jersey, wore “a gilt chain and locket.” However, by far, the most common type of jewelry found in these runaway ads were earrings or as they were often referred to, earbobs. Sall, an enslaved woman originally from Maryland, who ran from Bourbon County, Kentucky wore “stone bobs in her ears of a blue & white color, hung in with silk thread.” Betty, from Hanover Town in Virginia, wore “Silver Earrings set with white Stones.” Phillis from Boston wore gold bobs in her ears. Prussia, from New York, wore “gold wires in her ears.” Even 5-year-old Alice, who ran from Wando, South Carolina with her mother and brother, wore “silver drops in her ears.”

Hair

“A remarkable large suit of wool which she takes much pains in combing”

The descriptions of clothing and jewelry of enslaved women by their masters and mistresses were straightforward and objective. A recounting of objects that was indeed specific, but usually without judgment. When describing the hair of these same women, however, there was a range, from subjective, patronizing, and derogatory to descriptive, detailed, and direct. Quite often the hair of these women in many ads was referred to as wool. Lizzy is described as having “a long wooly head” and Hannah had “remarkable long hair, or wool.” Hair and wool were synonymous, but many ads do refer to other characteristics of hair.

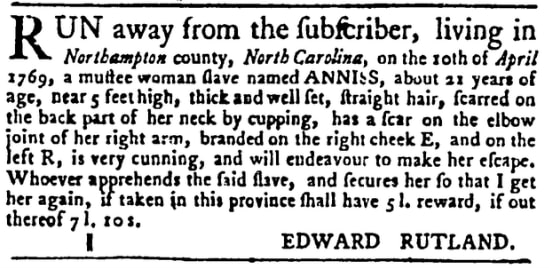

The texture of hair is often mentioned in ads as well. Annis, who ran from Northampton County, North Carolina, had straight hair. Peggy had “a bushy head.” Dinah, who escaped from her Warren, Rhode Island master in 1799, had “curled hair.” Twelve-year-old Ailcey, who ran to be with her mother in Alexandria, Virginia, had “tolerable straight hair.” Docia, described as a “very bright Mulatto, almost white” had “very course” hair. The texture of hair recounted in these ads varied as much as the women who ran.

There was also variation in the color of their hair. Moll, who lived in New Kent County, Virginia, had brown hair. Violetus, a 32-year-old woman who ran from Bridgewater, Massachusetts had “Hair of a yellowish colour.” Alice had “rather sandy hair.” Fanny, who ran in September of 1785, had “long red hair.” Betty from Essex, Virginia was “grey headed.” Anna Statia, who ran from the District of Columbia, had black hair. Elsa from Raleigh, North Carolina had “very black hair.”

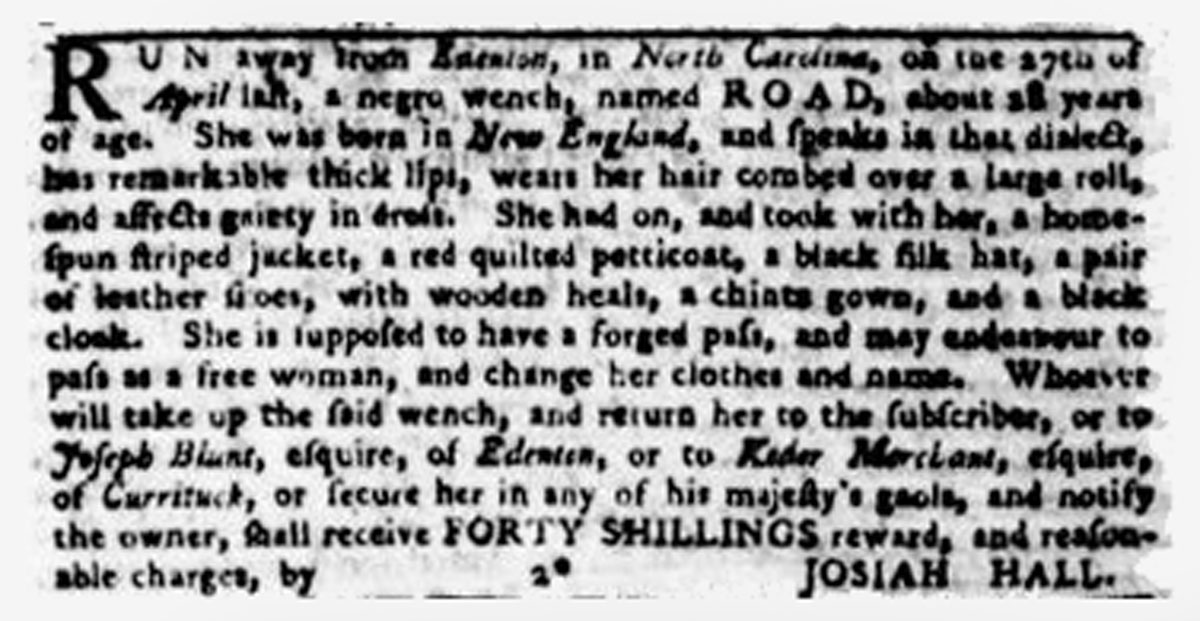

The variety of textures and colors that existed in the descriptions of these runaways, in no way compared to the variety of hairstyles that these women wore. Phebe wore her long black hair “generally clubbed”, or a knot or tail worn at the back of the head. Moll, who lived near Baltimore, generally wore “her hair filleted”, or used ribbon, string or strips of material to bind her hair or for ornamentation. Road, who was born in New England but absconded from Edenton, North Carolina, wore “her hair combed over a large roll.” Jane Wilson “usually wore her hair tied up in a knot on the crown of her head.” Kate, a native of Long Island, “generally wears her hair very high and straight up, over a roll, with a great deal of pomatum.” Charlotte, who ran from Norfolk, Virginia wore “her hair (which is of a sandy complexion) constantly platted.” And Flora, who ran away from Montgomery County, is described this way by her master: “She has long black hair, a part of which she sometimes plaits; which plait she continues on her head with a string or comb.” The assortment of styles listed here is just a small illustration of the ways in which these women fashioned their hair.

The information gathered for these posts only begins to scratch the surface of what can be gleaned from the runaway advertisements of these enslaved women. In addition to information about clothing, jewelry and hair, there is information about the languages these women spoke, the skills and trades they had, their religion, what musical instruments they played. There is even Tab, a woman who ran with only the clothes on her back and her little, white dog named, Fan. While using these ads as a reference, it is always important to remember that these women were in pursuit of freedom, liberty and the opportunity to live their own lives on their own terms as best they could. It is because so many women took that chance that we have these amazing resources that highlight their ability, their knowledge and their humanity. To learn more about how to approach runaway ads, see this blog post.

Hope Wright has been an employee at Colonial Williamsburg for over 30 years. She is currently an Actor-Interpreter. She loves to uncover stories about the lives and history of Black people. Hope loves to read and spend time with friends and family.

Resources

Alexandria Advertiser and Commercial Intelligencer, Alexandria, Virginia, July 28, 1803.

Boston Evening Post, Boston, Massachusetts, August 2, 1773.

The Centinel of Freedom, Newark, New Jersey, May 5, 1802.

Columbian Centinel, Boston, Massachusetts, October 29, 1803.

The Herald and Norfolk and Portsmouth Advertiser, Norfolk, Virginia, September 27, 1794.

Herald of the United States, Warren, Rhode Island, August 17, 1799.

Independent Journal, New York, New York, October 15, 1785.

Maryland Gazette, Annapolis, Maryland, October 4, 1770.

Maryland Journal and Baltimore Advertiser, Baltimore, Maryland, April 12, 1775.

Maryland Journal and Baltimore Advertiser, Baltimore, Maryland, October 5, 1779.

Maryland Journal and Baltimore Advertiser, Baltimore, Maryland, November 16. 1779.

Maryland Journal and Baltimore Advertiser, Baltimore, Maryland, December 17, 1782.

The New York Post Gazette: or, The Weekly Post-Boy, New York, New York, July 28, 1763.

Norfolk Herald, Norfolk, Virginia, October 25, 1798.

Norfolk Herald, Norfolk, Virginia, May 8, 1800.

North Carolina Journal, Halifax, North Carolina, October 6, 1792.

The Norwich Packet, Norwich, Connecticut, August 3, 1778.

Raleigh Register and North Carolina State Gazette, Raleigh, North Carolina, July 9, 1804.

The Royal Gazette, New York, New York, October 22, 1783.

South Carolina Gazette, Charleston, South Carolina, October 13, 1757.

Stewart’s Kentucky Herald, Lexington, Kentucky, October 25, 1796.

Virginia Gazette, Williamsburg, Virginia, October 27, 1752.

Virginia Gazette, Williamsburg, Virginia, January 29, 1767.

Virginia Gazette, Williamsburg, Virginia, March 26, 1767.

Virginia Gazette, Williamsburg, Virginia, June 7, 1770.

Virginia Gazette, Williamsburg, Virginia, May 12, 1774.

Virginia Gazette, Williamsburg, Virginia, March 11, 1775.

Virginia Gazette, Williamsburg, Virginia, June 15, 1775.

Virginia Gazette or American Advertiser, Richmond, Virginia, October 30, 1784.

Virginia Gazette or American Advertiser, Richmond, Virginia, December 17, 1785.

Virginia Gazette or American Advertiser, Richmond, Virginia, April 19, 1786.

Virginia Gazette or American Advertiser, Richmond, Virginia, May 17, 1786.

Virginia Gazette and General Advertiser, Richmond, Virginia, January 26, 1791.

Virginia Gazette and General Advertiser, Richmond, Virginia, June 4, 1799.

Virginia Herald and Fredericksburg Advertiser, Fredericksburg, Virginia, January 15, 1795.

Washington Federalist, Georgetown, District of Columbia, May 5, 1802.

Washington Federalist, Georgetown, District of Columbia, April 29, 1803.