[Note: the historical account described below includes domestic violence.]

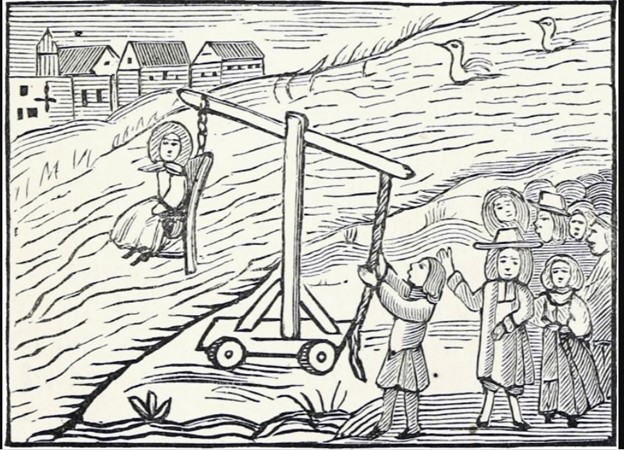

What do you do when you discover that your new husband isn’t the man you thought he was? Margaret Bannerman placed an advertisement in the Virginia Gazette.

“I have lived here many years in good credit,” she began “and laid out some thousands of pounds in trade, until October 1765 I was unfortunately married to Benjamin Bannerman.” Margaret had been a wealthy widow in Portsmouth, Virginia. Her new husband had recently kicked her out of their home. According to a later account, he had left her on the street at ten in the morning, “before every person in Portsmouth,” while “beating and bruising me in a cruel manner.” 1

According to her account, after their marriage, Benjamin began selling her assets to pay off his own debts. He sold her furniture, her liquor, and five enslaved people. He took £1,500 in cash. He “kept me prisoner, under three locks,” until she signed over title to three houses she owned, which he listed for sale.2 He had forced her to move to a smaller home, so that he could rent her home. Altogether, she estimated that he had taken £3,000 from her—a truly massive sum at that time.

My Husband, My Robber

According to Virginia law, as soon as Benjamin and Margaret married, they entered into a legal partnership which Benjamin would lead. As Margaret’s husband, Benjamin was legally entitled to sell her possessions and rent her property (though he could not legally sell her real estate without her consent).3 According to Margaret’s account, he had taken this remaining right away through coercion.

Unwilling to give up their property rights, many widows in revolutionary America simply chose not to remarry.4 So why had Margaret chosen to marry Benjamin? In a second notice published about six months later in the Virginia Gazette, she explained. Her “husband (or rather robber)” had forged letters that described Benjamin’s brother in Scotland dying and leaving him a fortune. She suggested that he had lured into marriage under false pretenses, using the invented Scottish inheritance to mask his intention of looting her estate. In fact, she explained, he had already used some of her funds to pay debts he had contracted in Antigua.

In November, Margaret took Benjamin to court to sue for a “separate maintenance.” While Virginia courts were extremely reluctant to permit divorce, they did sometimes require abusive men to support their wives in a separate household.5 Margaret won the case, and Benjamin was ordered to pay her 65 pounds a year and “to find security for 1300” pounds by the next day.

Separation

We know about the details of this court case because Benjamin described it at length in a public notice published in the Gazette in April. In his account, Benjamin turned the tables on Margaret. He depicted her as a killer, having murdered her two previous husbands. He claimed that she had “endeavoured to poison me” with a bowl of tea and refused to help him as he lay dying. In his account, she had even come to his deathbed after she poisoned him and fallen on her knees in repentance. When he recovered, he wrote, he had thrown her out of the house. Once out of the house, he claimed that she spent lavishly on clothing, on his credit.

Benjamin indicated that he would not pay, as the court had ordered, to support Margaret’s separate household. He claimed that the judges had been biased and unprofessional. In the case before his, he wrote, one judge had threatened to “kick the magistrate’s backside.” Ultimately, though, he claimed that he didn’t have enough money to meet the court’s demands. He was willing to pay her a smaller amount, “according to the income of my estate,” but if she couldn’t accept that, she “may get her decreed 65l. a year how she can.” Any sheriffs or constables coming to him about any business “shall be respectfully received (that decree only excepted).” He would not accept the verdict.

Margaret returned fire next month. She denied his charges but offered a few more allegations about Benjamin’s origins. He had come to Virginia pretending to be a wealthy Caribbean merchant with an inheritance in Scotland. But in fact, she wrote, he was forced to “leave Scotland for his misdemeanors, and sold, or served a number of years for his passage, in Antigua.” He had stolen some nicer clothing, “eloped and came hither.”

The matter seemed to be settled by the next spring. A Virginia Gazette advertisement indicated that Benjamin was selling two enslaved men to “satisfy a judgment obtained by Margaret Bannerman.” The next month, Benjamin placed another advertisement announcing his departure from Virginia.

It appears that Benjamin left Virginia for Philadelphia. His name appears again three years later in several Philadelphia newspapers, offering to purchase enslaved people.6 In one of these advertisements, he also offered for sale a large Virginia estate, probably one of those that Margaret had previously rented out.7 While it appears that he temporarily moved back to Virginia at some point, he announced in 1776 that he was leaving for the Caribbean.8 But by 1780, he died without providing for any heirs.9 If Margaret was still alive, she was a widow for a third time.

Margaret Bannerman claimed that she was the victim of a con artist who married her under false pretenses and then took advantage of property laws to swindle her. Benjamin Bannerman claimed to be an innocent victim of a murderous woman and a corrupt justice system.

Readers of the Virginia Gazette had a sensational window onto the brief, unhappy Bannerman marriage. It may be surprising that Margaret, a wealthy, respectable woman, would choose to share air sordid details in print. But colonial law left women, even wealthy ones, with few defenses against a cruel husband. The court and the newspapers were two of the only tools available to her for protecting her property and reputation. To rescue her good name and “good credit,” Margaret had to seek justice in public.

Learn More

Learn about the Virginia Gazette

Sources

COVER IMAGE: John Collett, The Elopement (1764). Oil on canvas.

- Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon), May 25, 1769, p. 3, col. 3.

- An advertisement for a home under Benjamin Bannerman’s name appears in Virginia Gazette (Purdie and Dixon), June 18, 1767, page 3, column 3.

- Marylynn Salmon, Women and the Law of Property in Early America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986), 14.

- Linda E. Speth, “More than Her ‘Thirds’: Wives and Widows in Colonial Virginia,” in Linda E. Speth and Alison Duncan Hirsch, Women, Family, and Community in Colonial America: Two Perspectives (New York: Routledge, 1983), 27–28.

- Glenda Riley, Divorce: An American Tradition (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1997), 26-27.

- Pennsylvania Packet, July 20, 1773, p. 4, col. 1; Pennsylvania Packet, March 8, 1773, p. 3, col. 3; Pennsylvania Packet, Feb. 28, 1774.

- Pennsylvania Journal, Aug. 31, 1774, p. 3.

- See advertisements in Virginia Gazette (Dixon and Hunter), April 18, 1776, p. 6, col. 2; Virginia Gazette (Dixon and Hunter), March 14, 1777, p. 7, col. 1.

- Virginia Gazette (Dixon and Nicolson), July 26, 1780, p. 3, col. 1.