This blog post, which is intended for mature audiences, contains adult terms, phrases and images that are offensive to modern readers. The words used in the text reflect the hardship, cruelty, and suffering women faced at the hands of Virginia's eighteenth-century court system. Including these words and phrases is done not to sensationalize the past but to ensure accuracy and to educate the modern reader. The language is used only in its original context and does not reflect Colonial Williamsburg's mission or values.

On a fall day in 1634, Joan Butler stood defiant at the bar of the Accomack County. Accused of calling Marie Drew a “common Carted hoare,” Joan’s conviction was swift, thanks to the testimony of two witnesses. When given the option of being dragged by a boat across King’s Creek or apologizing in front of the congregation the following Sunday, Butler chose to risk damage to her body over damage to her integrity.

Joan Butler’s neighbors would have likely called Butler a “scold,” a term only second to “whore” in its damage to a reputation. One hundred and forty years after Butler was dragged across King’s Creek, Ricard Starke, author of The Office and Authority of a Justice of Peace described the punishment for a scold:

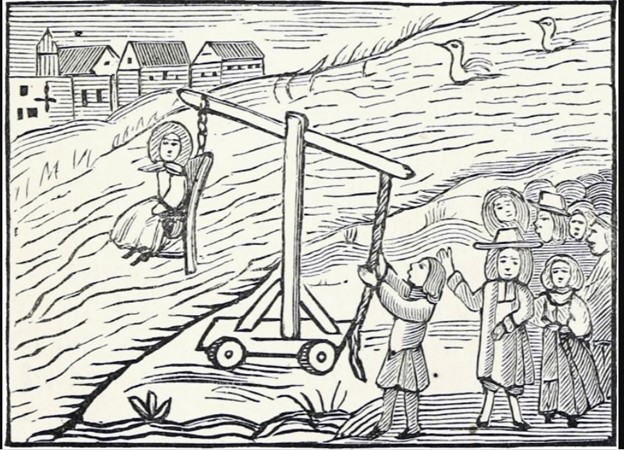

The punishment of a common Scold generally affords much merriment and seems well adapted to the Evil it is intended to prevent. A Woman convicted of this Offence [sic] is sentenced to be placed in a certain Engine of Correction, vulgarly called a Ducking Stool, and sunk in the Water two or three Times, until the Edge of her Fury is somewhat abated. Immersion seems best to suit this Offence, because it is thought by some that there is nothing which can stop the Mouth of a babbling Woman but the being put into that Medium, wherein her Tongue is totally deprived of the Power of Speech.

Women’s participation in the Virginia county court system was as complex as men’s. Nothing protected women from corporal punishment; the law doled out physical punishments regardless of gender. English Common Law and Virginia legislation did not explicitly address gender punishment, but the ducking stool and whipping post were common punishments administered to women, while the stocks, pillories, and gallows were primarily men’s domain. Women were hanged and men were whipped, but the divided nature of the implements of the “King’s Justice” tells a story of vulnerability and oppression.

Women of the seventeenth- and eighteenth- centuries were not yet considered the “fairer sex” and brutal physical punishments for women fit with the early modern English worldview. A society in flux, Britain turned to older tropes about women’s inferiority and the Sin of Eve, but expanded these beliefs, making women “monstrous.” Monsters, once considered wonders of God’s creation, frightened sixteenth-and seventeenth- English(wo)men. Gossipy, dishonest, with voracious sexual appetites, women were sometimes thought to be literal corruptions of human flesh. Enlightenment thought in the eighteenth-century recognized financially comfortable white women as people, but the legacy of “monsters” was still applied to poor and Black women. These women, because of their perceived inferiority, bore the brunt of violent punishments and had few laws that protected their interests or bodily autonomy.

Crimes associated with women correlated with beliefs about their character, although many of these crimes were introduced before the early modern period. Slander, “scolding,” adultery, and bastardy are some examples that applied the “women as monsters” trope to the legal system. Punishment for these crimes also were thought to counter women’s excessive passion. H. Mission, a Frenchmen visiting England in the 1690s, noted that the ducking stool cooled the “immoderate tongue.”

In 1661/1662, the Virginia legislature required every county to build ducking stools (see image), stocks, pillories, and whipping posts. The dry-land implements were constructed “neere the courthouse” and the ducking stool near water “in such a place as they shall think convenient.” Though it is clear that these structures existed in Virginia as early as 1631, but, as evidenced in Joan Butler’s case, not all counties had ducking stools that early. Butler instead was dragged behind a boat, a common way to punish women “scolds” when ducking stools were unavailable.

Whipping was a more versatile form of punishment, and, while occasionally used in women’s cases of slander, was often the sentence for white women convicted of sexual crimes. Fornication (extra-marital sex) and adultery (illicit relationships in which one or more parties were married) were recognized in a 1691 Virginia law as “filthy and grievous [sic] sins and offences as well against the law of God, as the law of man. . .” and carried a potential punishment thirty lashes on the bare back, well laid on. This punishment was an improvement over the violent and draconian Dale’s Laws of 1611-1619 – where fornicators were whipped three times a week for a month and adulterers put to death.

Successful prosecution of these “filthy and grievous sins” required two witnesses, making them difficult crimes to prove. Throughout Virginia in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, many men were acquitted for lack of evidence, but in some instances women’s guilt was obvious. Bearing a bastard, “a Person of vile or spurious Origin . . . all are termed Bastards who are born out of lawful Marriage,” was a serious offence with weighty consequences, especially for the poor and for indentured servants.

Not all bastardy cases were equal. Prior behavior and race of the child were also considered when magistrates passed sentence. Elizabeth James, a Northumberland County indentured servant, stood trial for bastardy in 1661 and named the child’s alleged father. The court found that the alleged father was not even in the county at the time. Furthermore, the justices of the peace were exasperated with her past antics as a “common and notorious strumpet.” She received “30 stripes upon her naked back.” The number of lashes were common for bastardy, but it is the language that is curious. Elizabeth’s transgressions were reflected in her punishment; all relevant laws and other entries in the Northumberland County order books say, “bare back.”

Women accused of having “mulatto” children faced additional punishments. Anti-miscegenation laws (a modern term for sexual or romantic relationships between white and Black people) going back to the late seventeenth century ensured that women who delivered mixed-race children were extensively punished. Whipping was still common, but hefty fines and up to five years of additional service for indentured servants were designed to deter inter-racial relationships. Children of white women and non-white men suffered from their status long after their mothers were whipped and humiliated. White bastard children were “bound out” as servants until the age of twenty; mulattos until the age of thirty.

Of course, women with access to resources could avoid the whip and the ducking stool. For certain crimes, Virginians preferred fines over violent punishment and would prefer collecting financially rather than embarrassing county residents. County court records recorded who paid the fine, though their motivations are though their motives were not always clear from these documents. Since most women charged with bastardy were indentured servants, the master or mistress often paid the fine. This was not an act of kindness. In addition to a further one to five years the indentured servant would have to serve their master for bastardy, an additional six months to a year was added for the cost of the fine.

Sometimes the motives seem more benevolent. Mary Pinhorn of York County was convicted of bastardy in 1730 and John Blair, gentlemen, and a justice of the peace, paid her fine. Two men paid Mary Wright’s fine for bastardy in 1740. Given Blair’s status and that there were two men who paid Wright’s fine, it is unlikely that any of the men in question were the fathers. John Hulet paid Mary Hughes’ fine in 1744. A second case brought against her in 1752 was dismissed, as Mary and John were now married. These are not examples of kindly men “rescuing” needy women, but rather a glimpse into how complex gender and punishment was in colonial Virginia.

Enslaved women’s experience of legal and extralegal punishment was an extension of their status. These women’s place in society rendered them impervious to certain legal punishments, but not to extralegal ones. Because of their lowly status, prosecuting enslaved women as scolds or slanderers was seen as a waste of the court’s time. If their language or behavior was thought to be disturbing the peace, the woman’s enslaver was expected to “correct” these women. Likewise, legal definitions of adultery, bastardy, and fornication did not apply to the enslaved. A woman’s flesh was thought to belong to her enslaver, so much so that were she raped by a white man who was not her owner, damages were paid to her enslaver with no recourse for her. “Bastardy” too did not apply, nor did delivering a “mulatto” infant. Enslaved men and women could not legally marry, making punishment for children born out of wedlock a moot point. As for mixed raced children, they inherited the status of their mother, not their father.

The whipping post became a common tool for legal punishment. Enslaved women were often tried and convicted for theft, among other crimes. Because theft of objects over a certain monetary value was a felony carrying the death sentence, sentences were sometimes commuted, but still harsh. In 1729, “Kate, a Negro Slave” was convicted of theft and was sentenced to twenty lashes at the York County whipping post and, for the same crime, twenty more lashes at the Williamsburg whipping post the next day.

For poor white and enslaved women, the King’s Justice was not just painful, it was humiliating. Joan Butler would have been stripped to her undergarments before being plunged into cold, weedy, fast-moving, or otherwise dangerous water. When she emerged, she would be soaked through, with her cotton or linen shift clinging to her body. Eighty years after Butler’s humiliating experience, Kate had to suffer the indignity of being whipped on her bare back in front of two audiences.

Joan’s and Kate’s stories are not unique in the history of crime and punishment in early Virginia. Hundreds, if not thousands, of now-unknown women suffered from the vestiges of a society that used brutality and humiliation to control “monstrous” women. Ducking did not “afford much Merriment” for women notorious for speaking their mind. The whipping post was a sinister reminder for women of all races that running afoul of the law had dire consequences for those on the margins.

Dr. Kelly M. Brennan has been a member of Colonial Williamsburg’s Research Department since 2018. She has had several positions throughout the Foundation and was an interpreter at the Courthouse of 1770.

Additional Readings

Bowler, Clara Ann. “Carted Whores and White Shrouded Apologies: Slander in the County Courts of Seventeenth-Century Virginia.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 85, no. 4 (1977): 411–26.

Brenner, Aletta. “‘The Good and Bad of That Sexe’: Monstrosity and Womanhood in Early Modern England.” Intersections Online 10, no. 2 (2009): 15.

Crane, Elaine Forman. Witches, Wife Beaters, and Whores: Common Law and Common Folk in Early America. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2011.

Kermode, Jennifer, and Garthine Walker. Women, Crime and the Courts in Early Modern England. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1994.

Snyder, Terri L. Brabbling Women: Disorderly Speech and the Law in Early Virginia. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2003.

Colonial Williamsburg is the largest living history museum in the world. Witness history brought to life on the charming streets of the colonial capital and explore our newly expanded and updated Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, featuring the nation’s premier folk art collection, plus the best in British and American fine and decorative arts from 1670–1840. Check out sales and special offers and our Official Colonial Williamsburg Hotels to plan your visit.