Regularly throughout the year, the Military Programs Department hosts a program called “Discussion of Military Topics.” We each focus on a topic that we have researched extensively. The area I specialize in is Regimental Colors (flags) during the American Revolution. Over the course of this blog post, I would like to share the progression of flags that served Britain, America, and specifically Virginia during the war. I should offer the caveat that I will confine my discussion (for the most part), to flags used on land ... flags of the Navy are a different subject altogether (though they are the point of origin for some land-based flags).

There are many popular stories that have been passed down about individual flags that have very few (or no) basis in fact, yet the stories have endured. I will try to use my 30 years of research on this topic to only share what can be backed up with historical facts. Wherever possible, I will link to other research articles that you may find interesting to read. Keep in mind that what I am able to share in the format of this blog only scratches the surface of what is available.

First, here are some useful vocabulary terms to keep in mind.

- Canton - A small portion within a flag, usually the upper inside corner i.e. that section of an American Flag that contains the stars.

- Colors - One of many terms (banner, ensign, guidon, flag, jack, pennant, standard) that equates to what we think of as a “flag” in modern terms.

- Field - The main area of a flag.

- Union - A symbolic joining of elements to represent an alliance (i.e. 13 Stars or Stripes for 13 colonies). Also, another term for Canton.

Why do I see British Flags around town?

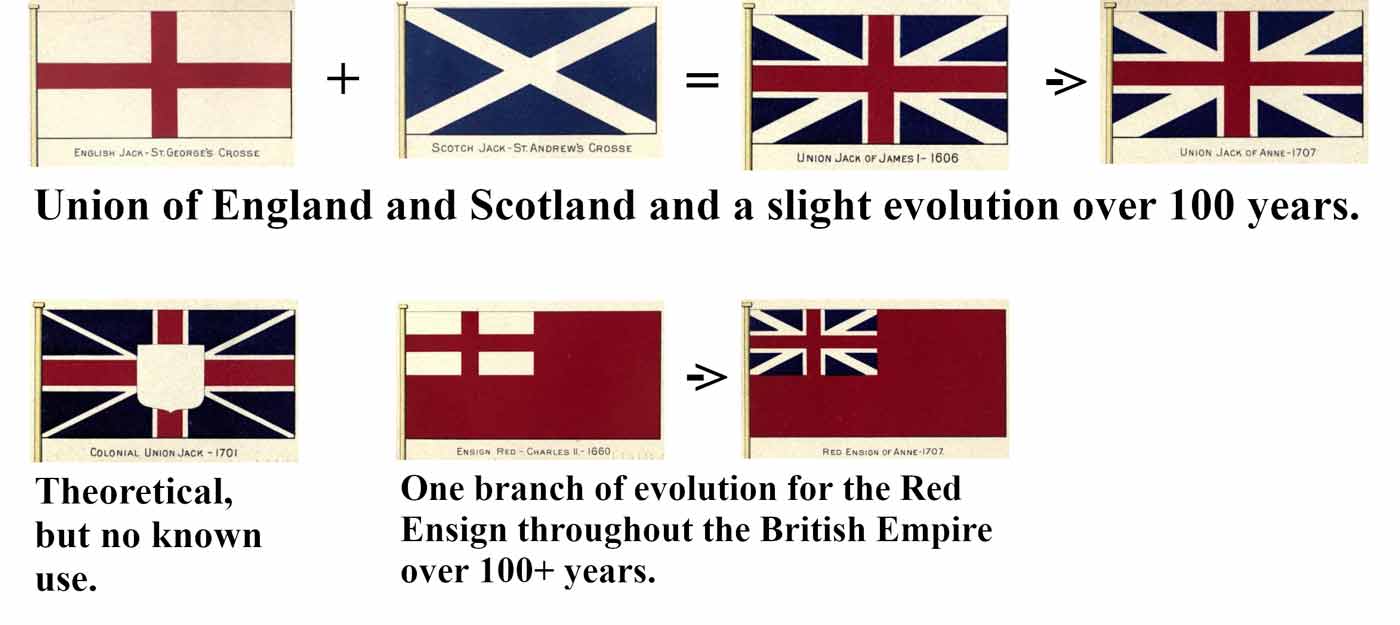

Williamsburg was capital to one of many colonies that belonged to the British Empire. As such, colonists were familiar with the use of British flags and emblems. Today you see a mix of several types used before and after the Revolution began, to represent the years we interpret in Williamsburg. The flag we commonly think of as “British” today was more commonly called the “Union Flag” or “King’s Colours” during the 18th century. That flag represented the uniting of England (St. George’s Cross) and Scotland (St. Andrew’s Cross) by literally joining their flags in “Union”. The modern version we are accustomed to looks slightly different since it incorporated the additional flag for Ireland (St. Patrick’s Cross) in 1801.

Union Flag vs. Union Jack

If it’s properly called the “Union Flag” or “King’s Colours,” why do we call it a “Union Jack” today? The two different terms are somewhat interchangeable, but each name implies a different use (and sometimes size). “King’s Colours” tend to be a specific size carried with a British Regiment of Foot (infantry). “Union Flags” are larger in size, usually flown over a ship (and implies in many cases that ship is part of the British Navy). The “Union Jack” is usually a smaller version of the same flag flown at the fore part of a ship called the Jackstaff. The flag flown at the aft (or rear) of a ship is usually an ensign.

Military vs. Civil

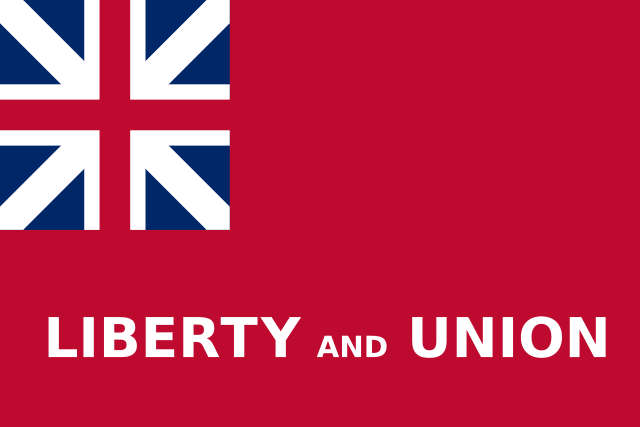

The “King’s Colours” were just that: a flag that usually represented some form of service to the King (i.e. Army, Navy). For the use of merchants at sea, and many other “civil” purposes, a different variation called an ensign was chosen. The ensign was to have the “Union” placed in the canton of the flag, and surround it with a larger field of solid red, which is where it picked up the name “Red Ensign.” The earliest forms of this ensign only used the St. George’s Cross in the canton for English use (St. Andrew’s in the canton for Scotish use). In 1707 Queen Anne merged this flag as well with a proclamation.

What about in British North America?

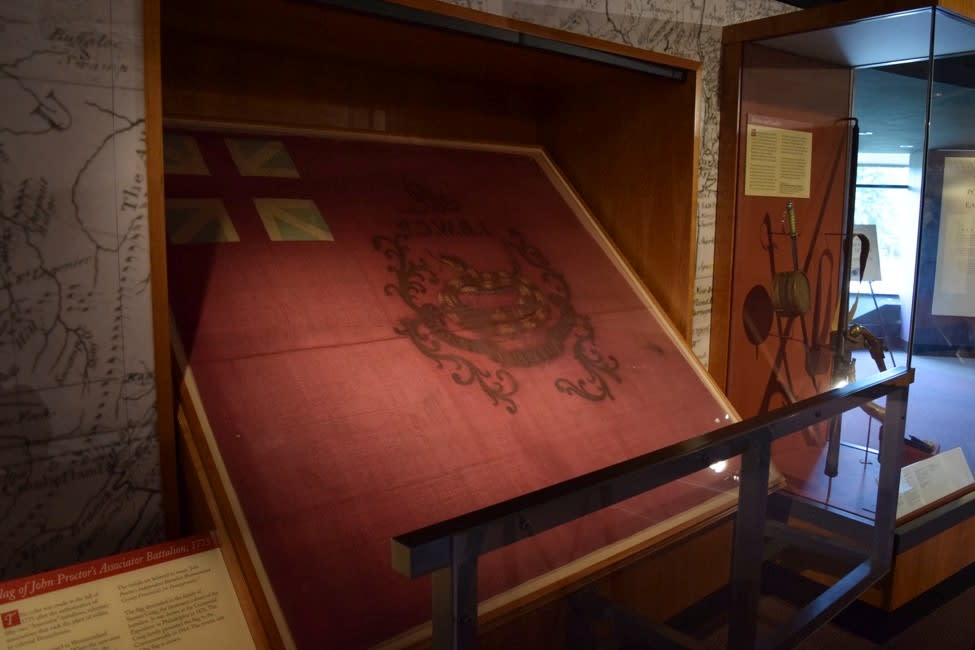

For British colonies there was a separate flag called a “Colonial Union Jack” or the “Escutcheon Jack.” Though specified for use, noted vexillologist David Martucci and many others believe there is no evidence it ever saw service. Instead different variations of the “Red Ensign” began to see use, first in the New England colonies, starting with the earlier version that included St. George’s Cross in the canton. Owing to religious disputes with the flag, for a time the St. George’s Cross was removed and a pine tree put in its stead, or sometimes inserted in the upper inside corner of the cross. Surviving flags of this New England type were used by militia units in the mid-1700’s and even later. Some units from Massachusetts to Pennsylvania used the proper ensign that contained the “Union Flag” and even added later additions to allow the flags to be used during the Revolution.

Did Virginia use the Red Ensign?

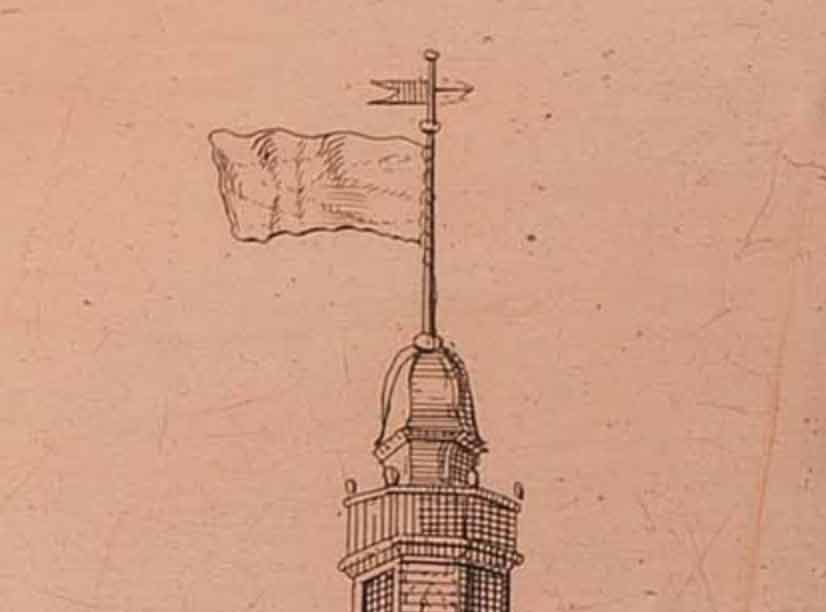

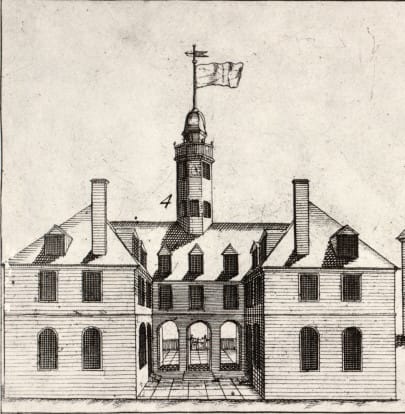

Good question. There have been a number of volumes on flags that detail how Massachusetts and New England varied their designs of the ensign. However, the vast majority of English colonies throughout the world (outside of New England) did use the “Red Ensign.” Many of those former colonies still use the ensign as their flags to this very day (with the addition of a colonial or royal badge within the field). There is one good piece of evidence that can link this flag not just to Virginia, but to Williamsburg as well. The evidence comes from the Bodleian Plate (an image that was crucial to the reconstruction of several major buildings during Colonial Williamsburg’s restoration. The image it contains of the Capitol building circa 1740 shows a flag flying above the cupola. In the most detailed view of the image you can faintly make out that the flag above the Capitol has a solid field and a canton inset in the corner. Sadly, the view is not detailed enough to be able to discern if the canton contains the St. George’s Cross (like New England flags), or the “Union,” but it is still a clue to us that one form of the “Red Ensign” is what was in use.

So next time you visit Colonial Williamsburg, keep in mind that in the 18th century very few flags would appear around the town. The one place where you would see a flag prior to the Revolution, would use something far different than what we see today! As for the rest of the flags you see around town today...that is a discussion for another day.

Further Reading

The following sources are just a few of many consulted that can give additional insight into the discussion. If you would like to know more, follow the links to read more articles and books on this topic.

- Before Old Glory, There Was the Taunton Flag. New England Historical Society

- Don’t Tread on Me: The Flag of Colonel John Proctor’s 1st Battalion of Westmoreland County, Pa. Fort Pitt Museum Blog

- Flag and Symbol Usage in Early New England. By David B. Martucci

- History of the Union Jack and flags of the Empire; their origin, proportions and meanings as tracing the constitutional development of the British realm, and with references to other national ensigns. By Barlow Cumberland

Josh Bucchioni has been an interpreter at Colonial Williamsburg for over 17 years, the first 4 leading school groups through the town, and the most recent 13 with Military Programs. Josh specializes in the study of Military Flags, primarily from the American Revolution through the American Civil War.