On this day in 1776, two vessels of the Virginia Navy prevented reinforcements from reaching Lord Dunmore.

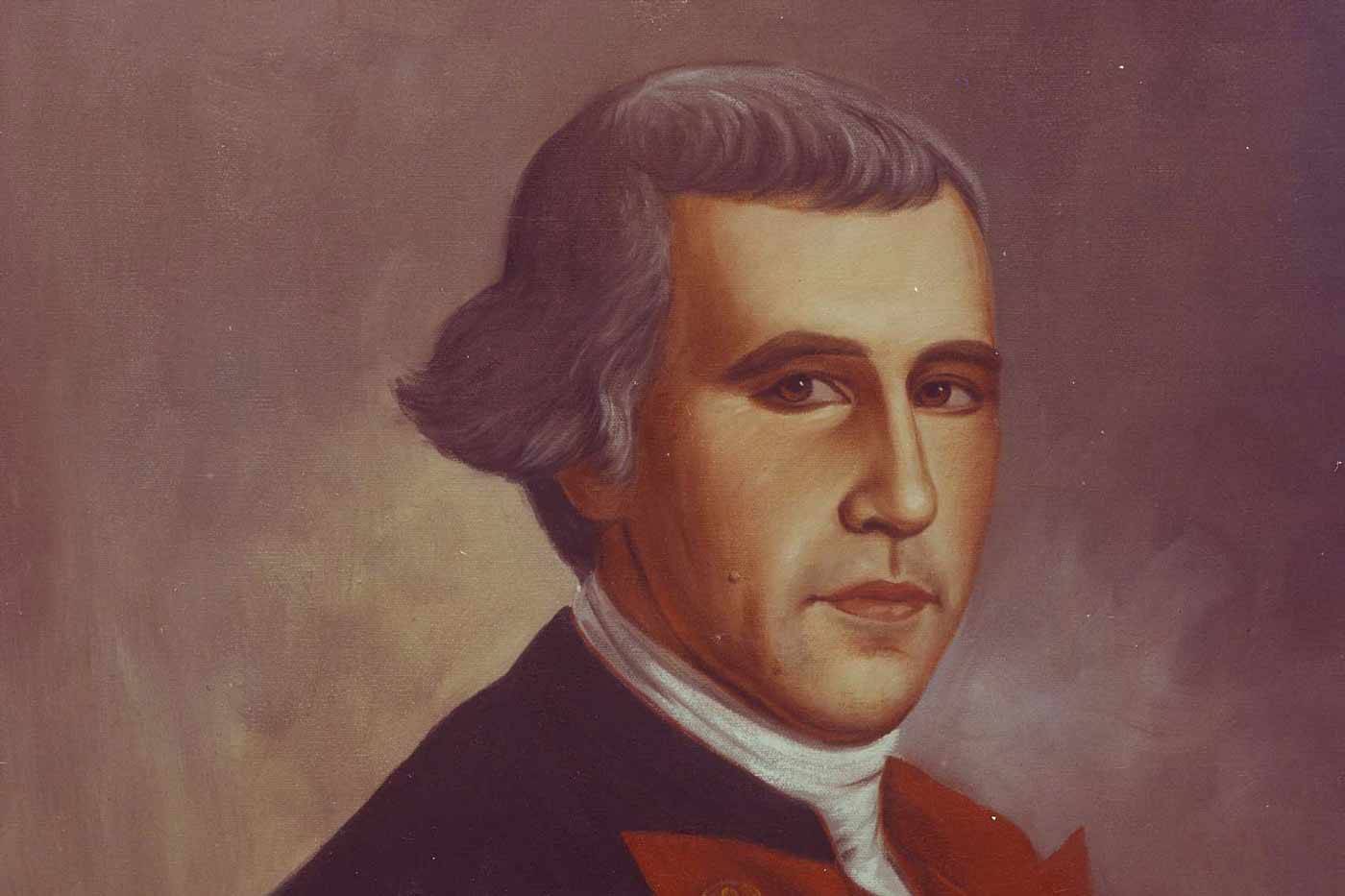

Nicholas Biddle was one of few captains in the Continental Navy who had previous military experience; from mid-June 1771 until early 1774, he had been a midshipman in the British Royal Navy and was even shipmates with a young Horatio Nelson aboard HMS Carcass. When word of the Boston Tea Party reached Great Britain, Biddle knew that harsh reprisals and likely armed rebellion would follow. He quickly turned in his midshipman’s warrant and returned to his native Pennsylvania. Biddle soon distinguished himself in the patriot cause: he commanded a small schooner on a daring run to the West Indies to bring back some six and a half tons of gunpowder in June 1775, commanded the galley Franklin for the Pennsylvania Navy, and was appointed captain of the 14-gun Continental Navy brig Andrew Doria in December 1775.

Captain Biddle and Andrew Doria were attached to the first squadron assembled by the Continental Navy under the overall command of Esek Hopkins. On March 3, 1776, Andrew Doria took part in the amphibious attack on New Providence. Less than a month later, she participated in the battle with HMS Glasgow, for which Esek Hopkins would eventually be relieved of his command. By late May, Andrew Doria cruised independently off the New England coast, hunting British merchantmen and/or small warships. Early on the morning of May 29, two ships were sighted in the distance, and Biddle’s ship prepared for battle. When Andrew Doria came abreast of the first ship, Biddle learned that this was the unarmed transport Oxford (the sixteen guns at her ports were no more than wooden decoys), which carried about one hundred Highlanders of the 42nd Regiment, including numerous wives and children of the soldiers. Her companion was the transport Crawford and carried a similar contingent from the 71st Regiment. Both vessels had been intended to augment British forces in Boston. All the soldiers’ weapons and accoutrements were moved to Andrew Doria, as were the Highlander and British naval officers from both transports. The soldiers of both regiments (numbering approximately 220) and their families were confined aboard Oxford, along with the British sailors. Captain Biddle placed an eleven-man prize crew on board, including Marine Lieutenant John Trevett, who kept a journal of the voyage.

Andrew Doria sailed in company with her prizes until June 11, when the sails of five other ships were spotted on the horizon. Biddle cautiously gave orders for his two prizes to scatter; he had no way of knowing the vessels were four merchantmen escorted by the 20-gun HMS Mercury. Biddle did not see or hear of either of the transports again until he returned to Philadelphia. In the Oxford's case, as soon as Andrew Doria was beyond the horizon, the Highlanders rose up and deposed the prize crew despite their own lack of weapons. “I could not blame them,” Trevett wrote, “for I would have done the same.” The former prisoners, however, commanded by a Mr. Canada, had no friendly navigator on board. They decided that their best course of action was to steer for Chesapeake Bay (which they estimated was directly southwest of their position) and attempt to join forces with Lord Dunmore, Virginia's beleaguered Royal Governor. Almost miraculously, Oxford's safely reached Virginia nine days after she was wrested from the Continental prize crew.

Oxford passed the Virginia Capes just before sunset on June 20 and was quickly approached by a pair of schooners. Having thought them to be pilot boats, Mr. Canada sent a boat with two Highlanders and rowed by one of the captured Andrew Doria sailors to ask after Lord Dunmore. As Lieutenant Trevett wrote, “…they informed us the Fowey, ship of war, lay 40 miles up James river, and they must immediately get under way, after giving 3 cheers they weighed anchor.” Little did the Highlanders know that Lord Dunmore operated at that time off Gwynn’s Island near the mouth of the Rappahannock River; the seemingly helpful pilot boats were in fact the schooners Liberty and Patriot, commanded by Captains James and Richard Barron of the Virginia Navy. Unbeknownst to the Highlanders, the Continental rower had secretly informed the Virginians as to the true situation aboard Oxford. Shortly before midnight, based on advice secretly forwarded by Trevett, the Virginians stormed aboard the transport and took her in the name of the United Colonies for a second time.

The next morning, Liberty, Patriot, and Oxford arrived at Jamestown, where the prisoners were disembarked and marched to Williamsburg. The Committee of Safety ordered that the Highlanders (together with their wives and children) be dispersed among the western counties of Virginia and employed under what wages they might choose to accept or held as prisoners of war. Oxford’s British sailors were given the option to join the Virginia Navy or march west with the Highlanders, and a handful of these sailors did indeed choose to serve in Virginia. Lieutenant Trevett and the prize crew from Andrew Doria were provided with travel money and eventually returned to Philadelphia. The transport itself was libeled against in accordance with resolutions by the Continental Congress, with the Virginian crews being entitled to half the proceeds of Oxford’s sale.

The Virginia Navy was established on December 1, 1775 when the Virginia Convention had called upon local Committees of Safety to “provide, from time to time, such and so many Armed Vessels as they may judge necessary for the protection of the several Rivers in this Colony.” During the American Revolution, the Virginia Navy launched nearly fifty vessels of all shapes and sizes: row galleys, sloops, schooners, brigs, and even had a 28-gun frigate under construction until it was burned in 1779 to prevent it's capture by the British. In most cases, these vessels were no match for the British Navy, and were forced to scatter and hide in shallow creeks whenever a substantial enemy ship appeared. When it came to smugglers, small privateers, and the occasional lost transport (like Oxford), the small ships of the Virginia Navy were just the thing to keep the dream of independence alive on the waters of the Old Dominion.

Michael Romero is a Colonial Williamsburg Interpreter working in both Orientation and Public Sites. Since 2016, he has been working to bring 18th century naval history to life. Michael has published work in Naval History magazine and NAI’s Legacy, and recently began work towards a Master’s Degree in Military History.

Further Reading

- Clark, William Bell. Captain Dauntless: The Story of Nicholas Biddle of the Continental Navy. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1949.

- Cross, Charles Brinson. A Navy for Virginia: A Colony’s Fleet in the Revolution. Richmond: Virginia Independence Bicentennial Commission, 1981.

- Morgan, William James (ed). Naval Documents of the American Revolution, Volume 5. Washington: Naval Historical Center, 1970.

- Romero, Michael. “Virginia’s Unconquered Liberty.” Naval History (October 2018), pp 42-47.